Posts Tagged ‘Bei Dao’

PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I first visited Berlin in the fall of 1990 just after Germany reunited. I was living in London and took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to witness history in the making. I returned on a number of occasions, researching scenes for a book, attending meetings, and visiting German PEN in preparation for PEN’s 2006 Congress. Each time Berlin’s face was altered as the municipalities east and west moved to become one city again.

PEN International’s 72nd World Congress, Berlin, 2006

At the time of PEN’s Congress in May 2006, Berlin was bedecked with water pipes above ground—pink, green, blue, red—before the city buried its plumbing and infrastructure beneath the streets. Portions of the city had the appearance of an amusement park; there were also sections of the Berlin Wall with its colorful graffiti still standing, more as art exhibit than stark barrier to freedom.

“Welcome to a United Berlin” the German PEN President headlined his letter to the 450 delegates and participants for PEN’s 72nd World Congress. The Congress theme “Writing in a World Without Peace” was challenged by the reunification of Berlin and Germany, a historic event which bode well for the prospects of peace and which stood in contrast to the history that had come before. Yet the globe was still in conflict in the Middle East, in Asia and in Latin America where writers were under threat.

“There are countries such as Iran, Turkey or Cuba, where authors are jailed because of their books,” noted International PEN President Jiří Gruša. Resolutions at the Congress addressed the situations for writers imprisoned or killed in China, Cuba, Iran, Mexico, Russia/Chechnya, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and other countries.

Left: Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) meeting at Berlin Congress. Karin Clark (Chair WiPC) and Sara Whyatt (WiPC Program Director). Right: WiPC Conference in Istanbul: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN/PEN Board), Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Jonathan Heawood (English PEN), Notetaker

Two months before in March, over 60 writers from 27 PEN centers in 23 countries had gathered for International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul where the WiPC planned a campaign against insult and criminal defamation laws under which writers and journalists were imprisoned worldwide. The conference also addressed the recent uproar over the Danish cartoons, impunity and the role of internet service providers offering information on writers, especially in China. A working group formed to support the Russian PEN Center which was under pressure from the Russian government.

Berlin, however, was sparkling and filled with the energy of reunification. “Today, this city—once separated by a Wall most drastically manifesting the division of Germany and Europe—has not only been re-established as the capital of Germany, but has simultaneously turned into a thriving meeting-place between East and West and North and South,” welcomed Johano Strasser, German PEN President. “Here in Berlin, history in all its facets—from the great achievements of German artists, philosophers and scientists to the crimes of the Nazis—has left its mark on the urban landscape.”

Left: German Chancellor Angela Merkel addressing PEN members at 72nd PEN Congress, 2006; Right: PEN International President Jiří Gruša speaking to PEN delegates and members at the Federal Chancellery; front row: German PEN President Johano Strasser, Chancellor Angela Merkel and PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman. [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

The keynote address by Nobel laureate Günter Grass challenged the conflicts around the globe and the countries engaged in them. “There has always been war. And even peace agreements, intentionally or unintentionally, contained the germs of future wars, whether the treaty was concluded in Münster in Westphalia, or in Versailles,” he said.

Nobel laureate Günter Grass addressing Opening Ceremony of PEN International’s 72nd World Congress in Berlin, 2006 [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As I sat on the dais on the edge of the stage listening to this renowned German writer, I leaned over to Jiří and said, If there is a standing ovation, I can’t stand. I was concerned. Grass could say and think whatever he wanted, but PEN was a non-political organization. Whatever my views of my country’s foreign policy, I was an American; I was also the mother of a son in uniform. Jiří leaned back to me and said in effect: Don’t worry, I won’t stand either. The speech ended with applause but no ovation, and then everyone got up and went to the next event.

It wasn’t my role to argue with Günter Grass even had the occasion allowed. But it was important that PEN assure the open space for debate existed which it did later in the Congress workshops and programs. PEN was filled with a multitude of points of view among its members; it did not have a litmus test of politics, only a commitment to the free expression of ideas. It offered a wide tent where views could be debated and challenged. Dogmatic political certainties often fell on their own in the alchemy of literature and imagination.

PEN members and delegates from around the world at Opening Ceremony of 2006 PEN Congress [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

Programs at the Congress also featured Nobel laureate and PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer and writers from around the world, including former International PEN Presidents Ronald Harwood, and György Konrád, Bei Dao, A.L. Kennedy, Margriet de Moor, Péter Nádas, Per Olov Enquist, Mahmoud Darwish, Duo Duo, Jean Rouaud, Johano Strasser, Veronique Tadio, Patrice Nganang and others. These writers participated in the literary events, including an evening of African literature and one of writers of German literature who had immigrated from abroad to Germany or had non-German cultural backgrounds. Afternoon literary sessions included prominent PEN writers introducing authors of their choice, an afternoon of essays and discussions on the theme Writing in a World without Peace and a lyric poetry afternoon.

PEN’s 85th anniversary coincided with the 60th anniversary of the United Nations. Both organizations had been founded after a World War out of an idealism that arose from desperate times with the hope that the future could be better than what had just transpired. “Both organizations were founded on a belief in dialogue and an exchange of ideas across national borders,” I noted in my address to the Assembly of Delegates. “When U.N. members were writing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the framers consulted, among other documents, PEN’s Charter.”

PEN also had a history with the city of Berlin, where PEN members had gathered in 1926 for the first international meeting of importance held in Berlin after World War I. At that Berlin Congress tensions had arisen among old and young writers, writers from the west and the east, and debate had flared about the political versus the nonpolitical nature of PEN. The debate that stirred in Berlin in part led to the framing of PEN’s Charter the following year.

Since those early days, PEN had grown in size beyond what the founding writers might ever have imagined. After the 2006 Berlin Congress, with the addition of centers in Jamaica, Uruguay, and Pretoria, South Africa, PEN had 144 centers in 101 countries in almost every time zone. The PEN world didn’t sleep. Someone, somewhere was always awake doing something. Through its centers PEN International participated in at least a dozen conferences around the world each year, including meetings of its standing committees. PEN thought globally but worked locally.

Berlin—with its own alterations and progress—proved a fitting location for the presentation of International PEN’s new Three-Year Plan. For the past decade, since the 75th Anniversary at the Congress in Guadalajara, PEN International had been in an organizational reformation. It now had a governing structure with a global Board that participated in decision-making; it had revised its Constitution and Rules and Regulations; it had developed a budget, increased its funding, and recently moved its offices into Central London to a larger space with cheaper pro rata rent and an elevator, which had meaning for anyone who had climbed the steep four (or five?) flights to PEN’s old offices. The staff size had also increased, and PEN had hired its first Executive Director, Caroline McCormick Whitaker, former Development Director from the British National History Museum.

International PEN Board meeting preceding 72nd PEN Congress in Berlin, May 2006. L to R: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Kata Kulakova (Chair Translation & Linguistic Rights Committee), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Chip Rolley (Chair Search Committee), Karen Efford (Program Officer), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International PEN President), Peter Firkin (standing—Centers Coordinator), Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Jane Spender (Programs Director), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair)

Because British charitable tax law had changed, the opportunity had also arisen to unite International PEN and the International PEN Foundation into one charitable organization: International PEN, Ltd, a step that would provide the legal framework and protection for the organization and PEN’s name, would limit personal financial liability of the Board and attract a wider funding base. At the Berlin Congress, resolutions and approval were endorsed for this step which would be finalized the following year at the 2007 Congress in Dakar.

Caroline Whitaker took the Assembly of Delegates through the Three-Year Plan which had been developed after widespread consultation with PEN centers and the Board. She acknowledged that PEN couldn’t do everything that everyone wanted right away, that it was necessary to focus resources even as PEN developed more resources.

The Plan, which had grown out of all the discussions and preceding plans, concentrated on PEN’s three missions: to promote literature, to protect freedom of expression and to build a community of writers. “International PEN will work regionally to connect the activity of its many Centers around the globe on these issues,” Caroline told the delegates.

All PEN’s Standing Committees met at Berlin Congress—Writers in Prison Committee, Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women Writers Committee and Peace Committee [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

In helping to develop PEN’s centers, the Three-Year Plan recommended International PEN focus on one region at a time, beginning with Africa where the 2007 PEN Congress would be held. International PEN would assist in programming and fundraising for development of PEN’s African Centers. The next regional focus would be Latin America, where PEN’s 2008 Congress was to be held. This rolling focus would allow the limited international staff to plan strategically. Regular daily work would still continue for the needs of centers in all regions.

PEN members met in workshops at 72nd Berlin Congress. Topics: PEN in the World—Global Issues; Education; the Strategic Plan; Centers; Networks and Partners; Asia and Central Asia; Middle East; Africa; Europe and Americas [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As International PEN’s work had taken me across the globe that year, I’d come to see that PEN and its members formed a kind of intricate net which helped hold civil society together, the kind of sturdy net used on hills to prevent landslides. In a way that is what PEN members did around the world. They helped prevent literary culture and languages and freedom of expression from slipping away by both their active programming and their defensive actions

At the 1926 PEN Congress in Berlin International PEN’s President John Galsworthy and PEN’s founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott had their voices recorded and preserved in a project of the German state. Galsworthy read a page from his Forsyte Saga. According to Dawson Scott’s journal, she recorded the following: “Even as individuals become families and families become communities and communities become nations, so eventually must the nations draw together in peace.”

It was a worthy, if not yet realized goal, but at least in PEN we had a global family.

Mayor’s reception for PEN members and participants at 72nd World Congress in Berlin, May 2006 [Photo Credit: Tran Vu]

Elections at 2006 Congress:

International PEN President: Jiří Gruša was re-elected for further 3-year term.

International PEN Board: Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian Center) and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN re-elected to the Board)

Vice Presidents: Toni Morrison (American PEN) and J.M. Coetzee (Sydney PEN) elected Vice Presidents for service to literature and Gloria Guardia (Panamanian Center) for service to PEN

Women Writers Committee: Judith Buckrich (Melbourne Center) re-elected as Chair

Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee: Carles Torner (Catalan PEN) stood down as Vice Chair, replaced by Josep Maria Terricabras (Catalan PEN)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 42: From Copenhagen to Dakar to Guadalajara and in Between

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

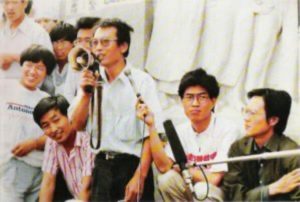

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East