Posts Tagged ‘freedom of expression’

One More Voice

I thought about ending this blog. The final post: December, 2018—just over ten years, over 100 posts. Informal reflections on a decade. Since February, 2008 when I first attempted this new form and posted, the volume of blogs around the globe has proliferated to an immeasurable dimension. Today with blogs, podcasts, Facebook posts, LinkedIn, Twitter, photos on Instagram and other platforms and apps I don’t even know or use, everyone is talking about everything. My email box is filled with messages and information and notifications I never asked for, with political points of view I can barely consider, polls and surveys I never fill out…except one where I answer NO whenever it appears: “Should Hillary Clinton run for President?” NO. This answer doesn’t represent a political point of view so much as a measuring of time and tides…and consequences. It is time for others.

And yet rather than ending this blog, I write again. Perhaps a politician can’t help running for office.

What is one more blog post launched into the universe? The freedom to express is one I don’t take for granted when that freedom is shrinking around the globe and can have dire consequences in countries like China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Mexico, Venezuela. What is one more blog post launched into the universe? Just that, one more voice, a point of view no else exactly has.

Some writers I know have turned to photography. I understand the turn. Below are photos from a few days south, away from snow and ice storms, a brief visit to sun and the promise of spring. Comment, post yourself, confirm someone is receiving. Happy winter’s end or summer’s end, depending in which hemisphere you live.

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

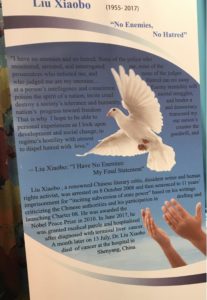

Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo died this past July in prison, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for his role in drafting Charter ’08 calling for democratic reform in China. Below is my essay in The Memorial Collection for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, just published by the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition and Democratic China.

I never met Liu Xiaobo, but his words and life touch and inspire me. His ideas live beyond his physical body though I am among the many who wish he survived to help develop and lead democratic reform in China, a nation and people he was devoted to.

Liu’s Final Statement: I Have No Enemies delivered December 23, 2009 to the judge sentencing him stands beside important texts which inspire and help frame society as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail did in my country. King addressed fellow clergymen and also his prosecutors, judges and the citizens of America in its struggle to realize a more perfect democracy.

I hesitate to project too much onto Liu Xiaobo, this man I never met, but as a writer and an activist through PEN on behalf of writers whose words set the powers of state against them, I can offer my own context and measurement.

Liu said June, 1989 was a turning point in his life as he returned to China to join the protests of the democracy movement. In June, 1989 I was President of PEN Center USA West. It was a tumultuous year in which the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was issued in February, and PEN, including our center, mobilized worldwide in protest.

In May, 1989 I was a delegate to the PEN Congress in Maastricht, Netherlands where PEN Center USA West presented to the Assembly of Delegates a resolution on behalf of imprisoned writers in China, including Wei Jingsheng, and called on the Chinese government to release them. The Chinese delegation, which represented the government’s perspective more than PEN’s, argued against the resolution. Poet Bei Dao, who was a guest of the Congress, stood and defended our resolution with Taipei PEN translating.

When the events of Tiananmen Square erupted a few weeks later, my first concern was whether Bei Dao was safe. It turns out he had not yet returned to China and never did. PEN Center USA West, along with PEN Centers around the world, began going through the names of Chinese writers taken into custody so we might intervene. I remember well reading through these names written in Chinese sent from PEN’s London headquarters and trying to sort them and get them translated. Liu Xiaobo, I am certain must have been among them, though I didn’t know him at the time.

In his Final Statement to the Court twenty years later, Liu told the consequence for him of being found guilty of “the crime of spreading and inciting counterrevolution” at the Tiananmen protest: “I found myself separate from my beloved lectern and no longer able to publish my writing or give public talks inside China. Merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his right to teach, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual could no longer speak openly. Whether we view this as my own fate or as the fate of a China after thirty years of ‘reform and opening,’ it is truly a sad fate.”

I finally did meet Wei Jingsheng after years of working on his case. He was released and came to the United States where we shared a meal together at the Old Ebbit Grill in Washington. I was hopeful I might someday also get to meet Liu Xiaobo, or if not meet him physically, at least get to hear more from him through his poetry and prose.

His words are now our only meeting place. His writing is robust and full of truth about the human spirit, individually and collectively as citizens form the body politic. I expect that both his poetry and the famed Charter 08, for which he was one of the primary drafters and which more than 2000 Chinese citizens endorsed, will resonate and grow in consequence.

Charter 08 set out a path to a more democratic China which I hope one day will be realized.

“The political reality, which is plain for anyone to see, is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government,” noted Charter 08. “The ruling elite continues to cling to its authoritarian power and fights off any move toward political change….

“Accordingly, and in a spirit of this duty as responsible and constructive citizens, we offer the following recommendations on national governance, citizens’ rights, and social development: a New Constitution…Separation of Powers…Legislative Democracy…an Independent Judiciary…Public Control of Public Servants…Guarantee of Human Rights…Election of Public Officials…Rural—Urban Equality…Freedom to Form Groups…Freedom to Assemble…Freedom of Expression…Freedom of Religion…Civic Education…Protection of Private Property…Financial and Tax Reform…Social Security…Protection of the Environment…a Federated Republic…Truth in Reconciliation.”

Charter 08 addresses the body politic. Liu Xiaobo’s Final Statement: I Have No Hatred addresses the individual, and for me resonates most profoundly. Its call doesn’t depend on others but on oneself for execution. He warned against hatred.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows). It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

At a recent conference a participant asked if Liu Xiaobo might have changed this statement if he understood how his life would end. A friend who knew him assured that he would not for he was committed to the idea. Liu Xiaobo’s commitment to No Enemies, No Hatred does not accede to the authoritarianism he opposed, but instead resists the negative. He aligns with benevolence and love as the power that nourishes the human spirit and ultimately allows it to flourish. Liu’s words and his ideas lived offer us all a beacon and a guide.

Reclaiming Truth In Times Of Propaganda

PEN International’s 83rd Congress in Lviv, Ukraine took on truth and words, history and memory, women’s access and equality, cyber trolling, fake news and threats to freedom of expression worldwide, including public panels focused on the three super powers: “America’s Reckoning—Threats to the First Amendment in Trump’s America,” “China’s Shame—How a Poet Exposed the Soul of the Party,” and “Putin’s Power Play—The Decline of Freedom of Expression in Russia.”

At its annual gathering PEN hosted more than 200 writers, editors, staff and visitors from 69 PEN centers around the world in the historic city of Lviv, the Cultural Capital of Ukraine and a UNESCO World City of Literature. Straddling the center of Europe, on the fault lines between East and West, Lviv changed its name and governing domain eight times between 1914 and 1944, passing from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to Russia, back to Austria, Ukraine, Poland, Soviet Union, Germany then back to the Soviet Union and now finally in the Ukraine.

The path of European history cuts through the city and can be seen in architecture, culture and conversation. Though writers celebrated literature in the western Lviv, fighting was still underway in eastern Ukraine and the Crimea. PEN’s Russian center didn’t attend the Congress at the same time a new PEN St. Petersburg center was elected. Other new centers joining PEN’s network included Cuba, the Gambia and South India.

In times of war, the first casualty is truth, noted PEN’s report “Freedom of Expression in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: External Aggressions, Internal Challenges.” The report and the Congress addressed the aggressive role of propaganda in conflict. In Ukraine, in Russia and worldwide there has been a proliferation of false narratives.

PEN’s report on Ukraine noted: “Despite significant improvements, democracy in Ukraine remains ‘a work in progress’ and, among other things, severe challenges to the enjoyment of the right to free expression remain. These include the use of the media to foster political interests and agendas, delays in reforming state-owned media; and intimidation and attacks on journalists followed by impunity for the perpetrators. On the other hand, public criticism is growing, albeit slowly, including demands for more transparent and unbiased journalism.”

In Russia authorities are taking increasingly extreme legal and policy measures against freedom of expression, according to a PEN/Free Word Association report “Russia’s Strident Stifling of Free Speech.”

No writers are in prison in Ukraine, but in the Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014, filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, an opponent of annexation, was arrested and is now serving a 20-year sentence inside a Russian prison on terrorism charges he denies. At PEN’s Assembly, delegates remembered Pavel Sheremet with an Empty Chair. A Belarusian-born Russian journalist and free speech advocate, Sheremet wrote for an independent news website and hosted a radio show where he reported and commented on political developments in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. He died in a car bomb explosion in Kiev July, 2016. Shortly before he was assassinated, he’d written about corruption among law enforcement in Belarus, Ukraine and propagandists in Russia. His murder remains unsolved.

Resolutions at the Congress also addressed writers imprisoned in Turkey, China, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, and Eritrea and killings in Mexico, Russia, Venezuela, Bangladesh and India. Concerns about increasing censorship in Hungary, Poland, India, Turkey, and Spain were acted on as was the restriction of linguistic rights for Kurdish writers in Turkey, Hungarians in Ukraine and Uyghurs in China.

Expressing concern about the abuse of Interpol’s Red Notice system by some member states “in order to repress freedom of expression or to persecute members of political opposition beyond their borders”, PEN called on the Council of Europe “to refrain from carrying out arrests…when they have serious concerns that the notice in question could be abusive.”

PEN expanded Article 3 of its Charter for the first time since the document’s inception over 90 years ago. The Assembly voted new language which would include a wider mandate, reaching beyond just opposing hatreds of race, class and nations to include by extension gender, religion and other categories of identity. Article 3 of PEN’s Charter, which can be linked to here, now reads: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

PEN also passed a Women’s Manifesto noting “the use of culture, religion and tradition as the defense for keeping women silent as well as the way in which violence against women is a form of censorship needs to be both acknowledged and addressed.”

At the Opening Ceremony author of East West Street Philippe Sands, whose grandfather was born in Lviv, narrated the origins of international human rights law and the concepts “crimes against humanity” and “genocide.” These legal frameworks were developed by two lawyers who passed through the very university where the delegates sat. The legal teams prosecuting at the Nuremberg trials after World War II used these frameworks to secure convictions, including the conviction of Hans Frank, Hitler’s lawyer who governed the area around Lviv and sent over 100,000 Jews to concentration camps and death.

“The Foundations of human rights law came from here,” Sands said. “Every individual has rights under international law.” The lawyers Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin studied at the university at different times and never met. One escaped to Austria then England, the other to America. Lauterpacht protected the rights of the individual with the concept he developed of “crimes against humanity” and Lemkin protected the group with the legal construct for “genocide.” Both men were on the legal teams that successfully secured convictions at Nuremberg.

“No organization in the world knows better than PEN the need to protect individuals and to protect others,” Sands concluded.

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President

Andrei Kurkov from Ukranian PEN and Carles Torner, Executive Director PEN International

At the closing ceremony author David Patrikarakos focused on the current situation as the 21st century unfolds and addressed “Fact, Fiction and Politics in a Post Truth Age.” He told the story of Vitali, who became a troll for the Russian state working at a Troll farm. “When Vitali went to the Troll farm, he had enlisted in the Russian Army; he just didn’t wear a uniform. He and others became their own army with a virtual information war, and it is effective,” said Patrikarakos.

As an unemployed journalist, Vitali developed propaganda, rewriting reports, doctoring news accounts to enhance Russia’s position then distributed these on social media, along with fake news, fake pictures and memes to a wide audience, all relating to Russia’s assault on the Crimea. According to Patrikarakos (Nuclear Iran: The Birth of an Atomic State), who has also written for the New York Times, Financial Times, Guardian, and Wall Street Journal, the Russian state spent $250 million to sow discord in its battle for Crimea.

In the Troll farm where Vitali and other journalists worked, the first floor focused on distorting news reports and circulating them. On the second floor people worked through social media, posting memes and making up ads; on the third floor bloggers wrote about how life was better in Russian and bad for Russians in the Ukraine and on the fourth floor, people posted comments on other sites.

According to Patrikarakos and his sources, there was a bag of sim cards to request new accounts, and people were encouraged to make the accounts in the names of females because women were more likely to be believed. “The first goal was to shore up and get true believers, to give a narrative and sow as much confusion on reality as possible,” Patrikarakos said.

After three months Vitali told his boss he wanted to quit. He wrote an expose of the Troll farm. When it came out, he received threats such as “Don’t you know you can get punched in the face.”

“As I went through towns of Eastern Ukraine, content had seeped into walls,” said Patrikarakos. “In Eastern Ukraine, Putin’s nervous system is on display. There is belief in fake news—that Ukrainians want to kill Russian speakers. Social media is supposed to connect us but it has also shattered unity and divided people; it sets people at loggerheads. The news that young people get depends on who they follow. We all follow who we like, and so prejudice is reaffirmed. Facts are less important than narratives. The new word in 2016 from the Oxford dictionary was ‘post-truth’ which is finding linguistic footing. The goal of many is not to trust truth but to subvert truth,” he concluded.

What can we do to counter this trend? Patrikarakos advised:

- Go out of your way to see people who don’t think like you.

- Go directly to the source of information and go to the news.

- Read those you don’t agree with.

- Read books. (Patrikarakos’ new book is More Than 140 Characters)

- Mistrust the mob.

- Beware of Click bait.

- Click off.

“Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

The train from Copenhagen airport to Malmö, Sweden took just half an hour across the 21st century Øresund Bridge, which spans five miles of water, then the train dove into 2.5 miles of tunnel. Looking out the window at farmland and the blue waters of the Baltic Sea, I imagined this journey was not so easy 74 years ago with Nazis in pursuit. In 1943 as the Nazis went to sweep Denmark’s 7800 Jews into concentration camps, Danish and Swedish citizens rallied, and 7220 people managed to escape in boats across this Sound to nearby Sweden. Thousands landed in Malmö where I was headed for a less dramatic, but still fraught, occasion.

Members of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) whose writers live inside and outside mainland China were joining writers from Uyghur PEN, Tibetan PEN and members from Inner Mongolia, along with writers from PEN Turkey and Azerbaijan for the First International Conference of Four-PEN Platform: “Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred.” Swedish PEN was providing the safe space for debate, discussion and strategies of action on human rights and freedom of expression. Just six weeks before, one of ICPC’s founding members and honorary President Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, died in a Chinese prison after serving nine years of an 11-year sentence for drafting Charter 08, a document co-signed by 308 writers and intellectuals calling for a more democratic and free China.

A recognized leader in China’s Democracy Movement, Liu Xiaobo’s loss was deeply felt. A number of the writers gathered knew and worked with Liu. Most knew at least one fellow writer in prison. Many now live in exile themselves. Almost half of PEN International’s writers-in-prison cases are located in the regions represented at the conference.

The theme “No Enemies, No Hatred”—drawn from Liu Xiaobo’s final statement at his trial—sparked the debate in Malmö.

Keynote speaker Nobel Laureate Shirin Ebadi challenged, “But I do have enemies and I do feel hatred.” Facing death threats from her government in Iran, she had to leave everything behind at age 63 and move to London.

“Liu Xiaobo said he had no hatred and no enemies, but he also never compromised with any dictators,” she noted. “We must fight against dictators but our weapons are our pens and are nonviolent. We must not be silent. We can’t compromise with governments such as China who would eradicate an ‘empty chair’ from the internet.” [When Liu Xiaobo was unable to attend the Nobel ceremony because he was in prison, the Nobel Committee placed an empty chair on stage to represent him. The Chinese government is said to have censored the term “empty chair” from the internet in China.]

“What is the use of a pen if Liu Xiaobo is dead?” challenged one writer. Another speculated that if Liu Xiaobo had known how his life would end, he would have changed his message. A friend of Liu’s assured that he would not because for him no enemies and no hatred was a spiritual commitment.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows),” Liu declared to the court at his trial. “It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy…. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate…. No force can block the thirst for freedom that lies within human nature, and some day China, too, will be a nation of laws where human rights are paramount.”

Within this frame and this hope, stories of persecution were exchanged among the Tibetan, Uyghur and Mongolian writers in China and among writers from Azerbaijan and Turkey, where over 150 writers and journalists are currently in prison and over 100,000 judges, academics and civil servants have been fired.

Uyghur and Mongolian writers noted that starting September 1 the Uyghur language is banned from all schools.

“The Chinese call all Uyghurs terrorists,” said one participant. “I have never seen a gun or a bomb in my life, but my name is on Interpol’s list because of my pen. I am a German citizen, and I was in Italy, invited by the Italian Senate when Italian police arrested me because the Chinese government put me on a terrorist list because I speak out for the Uyghurs.”

Can one operate against totalitarian, oppressive governments without hatred and enemies? The question remained unresolved, but participants agreed that protest and actions needed to remain nonviolent. To amplify the voices of the writers who were in prison, those outside could publish them, protest to their governments and recognize the writers with awards. Implicit was a belief in the power of culture and ideas to ultimately change society.

The 2016 Liu Xiaobo Courage to Write Award was given at the conference to Hu Shigen and Mahvash Sabet. Writer and lecturer Hu Shigen spent his career in the Democracy Movement since 1989 Tiananmen Square when he was arrested for “counterrevolutionary propaganda” and sentenced to 20 years in prison and after release was arrested again for “subverting state power” and returned for seven and a half years in prison where he still resides. Mahvash Sabet, a teacher and noted Baha’i poet, was detained for her faith and for “acting against the security of the country and corruption on earth” in Iran and is now serving a 20-year sentence in Evin prison in Tehran. Her friend Shirin Ebadi accepted the award on her behalf.

Other cases highlighted by the conference included Ilham Tohti, Nurmuhemmet Yasin, Gulmire Imin, Memetjan Abdulla, Gheyret Niyaz, Zhao Haitong, Omerjan Hasan, Qin Yongmin, Zhang Haitao, and Mehman Aliyev. The gathering also highlighted the situation of Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo’s wife, who is believed still under house arrest. Many are working in the hope of getting her out of China.

When Shirin Ebadi was presented a statue of Liu Xiaobo, she noted that it would sit beside a statue she’d been given of Martin Luther King.

Dr. King’s writing of 54 years ago in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” read at the closing demonstrated the power of ideas and words to endure long after their author has passed away: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

In Turkey, a show of solidarity with writers behind bars

Commentary: For the first time in two decades, Turkey is again the largest jailor of writers and publishers in the world. A PEN International delegation tried to visit a prison where most are incarcerated.

By Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, published in The Christian Science Monitor, February 3, 2017

Snow was falling outside Silivri prison as we drove up the road bordered by high wire fences. A senior delegation of PEN International from Europe, North America, and the Middle East had come to Turkey in solidarity with the more than 150 Turkish writers and publishers now in prison. The majority of these were incarcerated behind the walls of Silivri.

For the first time in two decades, Turkey is again the largest jailor of writers and publishers in the world. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who came to power in 2002, civil institutions have been increasingly circumscribed. In the past six months more than 170 news outlets have been closed by the government. A third of Turkey’s judiciary – judges and prosecutors – have lost their jobs and/or been put in prison. University presidents have been fired; thousands of academics have been forced to resign, and more than 140,000 civil servants and military personnel have been purged; a third of these are now in detention. Ever since a coup attempt last July, Turkey has existed in a declared “state of emergency.” Those who oppose the government have been labeled and charged as “terrorists” or “supporters of terrorist organizations.” The crackdown that was already under way before the coup attempt has escalated.

At Silivri, our delegation was restricted to a remote parking lot. The prison officials had been notified the delegation would be arriving, but the gendarmes who encountered us appeared unprepared. Eventually they returned us to our minivans and encircled these and blocked us with police vehicles as they collected our passports. A young gendarme with an assault rifle boarded our bus, impeding our exit for almost an hour, though he appeared unsure of what he was supposed to do with us except keep us from taking pictures. Finally the delegation, which included three current and former International PEN presidents, including the current chair of the Nobel Prize for Literature, were escorted away from the prison. There was no interchange with prison officials or meetings with the writers behind bars. The cars were stopped again outside the grounds by the police, and our passports were once more collected. After approximately two hours, our two white minivans turned back to Istanbul.

Earlier, in the Turkish capital of Ankara, a smaller delegation of PEN met with the minister of Culture and other government officials to protest and express deep concern over the restriction of free expression and the imprisonment of writers and publishers in Turkey. PEN questioned the legitimacy of the constitutional referendum President Erdoğan is putting on the ballot this spring. The referendum will expand the powers of the presidency, giving Erdoğan the ability to suspend parliament as well as rights and due process, “extorting individual rights and freedom” by statutory decree. It could allow him to stay in office until 2029. While PEN, which promotes literature and defends freedom of expression worldwide, does not take political positions, it challenged the legitimacy of a referendum held during a state of emergency, when opposition voices are silenced.

After our delegation returned from the prison to Istanbul, we met with recently released writer Asil Erdoğan (no relation to the president), linguist Necmiye Alpay, and others, including the spouses of writers still in prison or killed. “It is not our husbands in prison, but journalism,” said the wife of one. “Journalism is a prerequisite for a country to have a free press. If we don’t have a free press, we can’t be considered anything. Don’t use the word “journalist” and “terrorist” together. It is very sad to see.”

Several of the writers noted that often no indictment is made when individuals are detained. They are held without charge because the prosecutors can’t find anything to charge them with. See #Journalismisnotacrime.

A new effort

One newspaper, Özgür Gündem, which had a large Kurdish readership, was shut down in August after 25 years. But a new newspaper, Demokrasi, has grown up out of its staff and readership.

At the top of a steep four-floor walkup, writers, photographers, and editors work to put out the daily paper with a readership of 30,000. The design and layout team work elsewhere as do some of the writers and other organs of the paper, in the belief that the more decentralized the operation, the better chance it has to survive.

“The government wants to eliminate the Kurdish movement – the language, the news we report. They want a single state, single religion, single language,” said one of the editors. “Kurds are not only the target; our newspapers are the target. We are OK with a single flag, but we don’t want religion and language imposed.”

The Turkish government has fought with Kurdish separatists for decades. A cease-fire from 2013-15 held out prospects for a more lasting peace and for the allowance of Kurdish language and culture to be recognized as part of Turkish identity. The rapprochement broke down, however, after the predominantly Kurdish HDP party won enough votes in June 2015 to secure seats in parliament and deny Erdoğan and his AKP party its parliamentary majority and the supermajority he was seeking for his constitutional changes. Hostilities with the Kurds were renewed shortly afterward. A new election was held in November 2015, and the AKP party won its majority.

The gray-haired editor of Demokrasi spoke calmly behind an empty desk in a sparse room with pale yellow walls. He acknowledged that the state police could come at any moment to take him away, but there would be others to take his place. “We received support from 100 journalists who volunteered to be editor-in-chief at Özgür Gündem. Thirty-seven of those are now on trial. But it is not a problem for us to repeat.”

As we left the Demokrasi office, the editor with his photographer stood at the top of the stairs in the shadow of a half-opened door, the light behind them. “Thank you for solidarity!” he said.

When we emerged, the sun was setting. The winding backstreet was filled with people as the lights of shops and apartments readying for dinner flickered on, and the snow continued to fall.

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman visited Turkey as part of a delegation from PEN International, where she is a vice president. Ms. Leedom-Ackerman is also a former reporter for the Monitor.

(Click here to read the article at The Christian Science Monitor.)

Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

The last time I saw Şanar Yurdatapan we had coffee in the press building in Istanbul after Human Rights Watch released its 2016 World Report “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society”. I’ve known Şanar for almost 20 years, ever since I headed PEN International’s delegation for his first Initiative for Free Expression in Istanbul in 1997.

A noted and popular musician and song writer, Şanar has dedicated the last decades to defending and trying to open up space in Turkey for free expression. He’s done so by monitoring, reporting and organizing on behalf of writers and artists under threat. At our coffee a year ago he told me he was retiring, or at least going back to song writing and handing over the mantle of leadership to the younger generation.

However, in the past year freedom of expression has been under siege in Turkey with 150-170 writers and journalists now in prison and hundreds of news organizations closed down. This past week Şanar was called before prosecutors for his advocacy on behalf of the closed newspaper Özgür Gündem, (Turkish for “Free Agenda”), the chief newspaper read by Kurds.

“It is both the duty and the right of a journalist to report; his is freedom of information at the same time and right to freedom and right of all of us,” Şanar is reported to have told the court.

At the end of the hearing the prosecutor demanded that Şanar be imprisoned for over ten years for “propaganda for the organization” under the Anti-Terror Law. The hearing is January 13, 2017. Şanar is now 75.

Since the failed coup in July the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has increased the detainment and arrest of writers, journalists and academics for their peaceful opposition to his policies. These have included noted novelist Asli Erdoğan and leading linguist Necmiye Alpay, who spent her 70th birthday in detention. Brothers Ahmet Altan, a novelist, and Mehmet Altan, an academic, are held in maximum security Silivri prison facing terror charges, unable to receive books, letters or any communication from outside or to visit the prison library.

As the year 2016 ends with an increase of terror attacks around the world, with a new administration about to take power in the U.S., with existing administrations struggling to hold onto power in Europe, with a collapsing Syria and a continual tide of refugees around the world, with an odd dance between super powers and aspiring super powers, the single citizen voice can get overlooked. But history has shown that when the individual voice, especially those of writers who dissent, gets stifled, the arc of history is bending towards conflict and away from peace which leaders and citizens say they want.

In the new year PEN International hopes to go to Turkey to add support firsthand for Turkish writers and for the important role they play right now in keeping that arc from bending too far backwards. We will watch and argue for the fate of Şanar and others and hope that he will be writing songs in the years ahead, and not from prison.

Thanksgiving and Healing

The American holiday Thanksgiving is my favorite, a time when family and friends gather and take a moment to give gratitude for the good in their lives and the lives of their communities. This year of 2016 has been a rough one.

In Washington, DC, where I live, the political discourse on all sides has been as uninspiring and acrimonious as any in my lifetime. No matter one’s political affiliation, consensus is that the recent presidential campaign has left us exhausted with the national conversation in need of elevation and inspiration.

Many opposing the election results have taken to the streets peacefully to articulate their concerns and their fears. The crowds include the young—high school students who are not yet old enough to vote—and the retired as well as the population in between. Whatever one’s vote, I take heart that for the most part these protests are not violent and can be heard. I take heart that the leadership in the nation has accepted the transition and will try to make it successful and that in practice we do not jail or shoot opposing voices or those writing about the opposition. This seems a minimum standard for a democracy, and though it has seen exceptions, in this season of thanks, I am grateful and hopeful that will abide.

Historically Thanksgiving was a day to give thanks for the harvest of the preceding year. In the U.S. the first Thanksgiving is documented in 1621 at Plymouth (now in Massachusetts). The harvest was good, and the new settlers and the local Wampanoag tribe shared the feast, though more uneasily watching each other than we were told as school children. During the American Civil War Abraham Lincoln advocated the story of Pilgrims and Indians eating together to try to encourage people in a divided nation to come together.

Healing occurs one action at a time, one forgiveness, one helping hand, one quiet good deed. Citizens can take the lead. I am hopeful that we individually—the people—will build bridges and not walls. Happy Thanksgiving!

Building Literary Bridges: Past and Present

Gathered in the ancient city of Ourense, Spain in the heart of Galicia, writers from around the world celebrated history, debated the present and committed to the future of literature and freedom of expression at PEN International’s 82nd Congress organized around the theme “Building Literary Bridges.”

Two hundred poets, novelists, dramatists and nonfiction writers from approximately 75 centers of PEN agreed to embark on a three-year global campaign to increase opportunities for displaced writers worldwide. Responding to the unprecedented flow of refugees, migrants, and displaced, all of which include writers and those whose stories need to be told, the 95-year old literary organization will undertake an initiative to put storytelling and literature at the center of an effort to heal and expand opportunities. Through its 145 centers, PEN will develop programs that will include residencies, workshops, mentoring, education and publications. The full scope of the campaign will be announced December 10, Human Rights Day.

Founded in 1921 out of the chaos and refugee flows after World War I, PEN anticipated and protested the suppression of freedom of expression in Nazi Germany prior to World War II and defended writers throughout Europe during the war, offering haven and setting up PEN centers in exile.

“PEN responds to the crises of our times,” said PEN International President Jennifer Clement. “We are writers. We believe in imagination.”

The 82nd Congress began with heartening and dispiriting news. Iranian-Canadian writer Homa Hoodfar was released from Iran’s Evin prison at the same time news arrived that Jordanian columnist Nahed Hattar had been gunned down outside court by a fundamentalist who claimed Nahed deserved to die for his ideas.

This pattern of good and terrible news also emerged in the past year with early releases of imprisoned writers in Tibet, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Vietnam, Qatar and Colombia at the same time the situation deteriorated with more arrests and killings in Bangladesh, China, Turkey, Ukraine and other countries.

The tradition of an Empty Chair at the PEN Congress sessions highlighted the cases of imprisoned Egyptian novelist Ahmed Naji, Kurdish journalist Asli Erdogan, Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour, and Gui Minhai, a bookseller in Hong Kong, who was kidnapped by the Chinese government while he was in Thailand.

Gui’s daughter, a Swedish citizen as is he, sent a letter to the Congress: “In the end, this is not about my father as an individual…. This is about China actively extending its control far beyond its own borders. This is about China kidnapping and illegally detaining more and more people because of their political beliefs. It’s about European citizens no longer being able to know that their human rights will be protected.”

Discussing “Literature as a Tool for Empowerment,” delegates shared ongoing projects, including working with young writers in schools and in prisons. Lebanon PEN Center’s delegate noted, “I discovered the tremendous effect from creative writing to express trauma and help people tell their stories. We have 1.3 million Syrians in Lebanon. We have a big responsibility. We see the empowerment of civil society through literature.”

In Mali and Sierra Leone, the PEN centers work with students and young people in post-conflict situations. The Mali delegate spoke about workshops with Tuareg warriors who had fought on the battlefield in the Sahara. When they returned home, they had lost their dignity and positions and were migrants so they went to join the ranks of Gadhafi. After Gadhafi was toppled, there was a big problem, he said, and conflict. The Mali PEN Center helped organize writing workshops which led to publishing books. Hundreds attended these workshops and were able to tell their stories and see them published.

PEN’s earliest work to protect writers began when poet Federico Garcia Lorca was arrested at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. PEN President H.G. Wells sent a telegram protesting, but it arrived too late and Lorca was executed. At the 82nd PEN Congress, Lorca’s niece Laura opened the Assembly with Lorca’s poem Sonnet:

I know that my profile will be serene

In the north of an unreflecting sky.

Mercury of vigil, chaste mirror

to break the pulse of my style.

For if ivy and the cool of linen

are the norm of the body I leave behind,

my profile in the sand will be the old

unblushing silence of a crocodile.

And though my tongue of frozen doves

will never taste of flame,

only of empty broom,

I’ll be a free sign of oppressed norms

on the neck of the stiff branch

and in an ache of dahlias without end.

–Federico Garcia Lorca

Spring and Release

I saw the first daffodils today…and forsythia…and the buds on cherry blossom trees. Spring with its regalia is starting to blossom, at least here in Washington, DC.

In the freedom of expression community renewal is heralded this week by the release of writers from prison in a number of countries, including Qatar, China and Azerbaijan. While the writers were unjustly imprisoned in the first place and many hundreds still languish in jails because they have offended governing powers, the releases of Qatar poet Mohammed al-Ajami after almost five years in prison and Chinese writers Rao Wenwei and Wang Xiaolu and half a dozen writers in Azerbaijan are cause for quiet celebration.

Qatar: In the fall of 2013 another PEN colleague and I stood outside the sprawling prison in the desert around Doha where Mohammed Ibn al-Dheeb al-Ajami was held in solitary confinement. After meetings with Justice Ministry officials, we’d understood we would be allowed into the prison for a visit. However, after five hours waiting in the desert wind, we were denied access. Al-Ajami’s family, who were visiting inside, told us later that Al-Ajami knew we were there and took some heart in that. Al-Ajami was imprisoned for “insulting the Emir” in two poems which he read at a private apartment in Cairo but which were surreptitiously recorded and posted by a student on YouTube. One of the poems “Tunisian Jasmine” expressed support for the uprising in Tunisia that launched the Arab Spring and challenged rulers throughout the region. Al-Ajami, who is the father of four, was originally sentenced to life in prison, reduced to 15 years.

PEN centers around the world, including American, Austrian, English and German PEN worked on his behalf as did Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and other organizations championing freedom of expression. Many voices protested, many hands tried to push open the prison door. Just last week at a Washington dinner I noted Al-Ajami’s imprisonment to an individual headed to Qatar for high level meetings. Those who deal with Qatar are always surprised that this Emirate which boasts education and partnerships with Western universities would imprison a poet for his poems. It is not a comfortable outcome that it is a pardon and not an apology by the Emir which brought about Al-Ajami’s release, but it is still cause to be glad.

China: There are more than 40 writers in prison in China, including Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo. Recently two—Rao Wenwei and Wang Xiaolu—were released early. Rao Wenwei is a writer charged with “inciting subversion of the state power” for articles published on the internet. His 12-year sentence was cut short by four years with his release. Wang Xiaolu was arrested for a story on the stock market crash on suspicion of “fabricating and disseminating false information on the trading of securities and futures.” Through the efforts of PEN centers, particularly the Independent Chinese PEN Center, the cases and situation of writers in prison in China stay at the forefront of protests.

Azerbaijan: Half a dozen writers are being released in Azerbaijan this month. The Baku Court of Appeals is expected to release journalist Rauf Mirkadirov today, according to Sports for Rights coalition which includes PEN, commuting his six-year prison sentence to a five-year suspended sentence. President Aliyev has signed a pardon decree that includes 14 political prisoners, including the writers Parviz Hashimli (journalist), Abdul Abilov (blogger), Hilal Mammadov (journalist), Omar Mamedov (blogger) and Tofiq Yaqublu (journalist). The European Court of Human Rights also issued a judgment in Rasul Jafarov’s case finding violations of Rasul’s rights to liberty and security. Rasul is expected to be released shortly. Dozens of political prisoners, however, remain in Azerbaijani jails, including journalists Khadija Ismayilova and Seymur Hezi.

(*For background on any of these cases or the many remaining political prisoners in Azerbaijan, here’s the full list with case details: http://www.helpsetthemfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/The-list-of-Political-Prisoners-in-Azerbaijan_December-2015.pdf)

View on the Bosphorus: Rights in Retreat

I’m sitting on the Bosphorus today in Istanbul looking across to the Asian side over the balustrade of a European porch. I’ve been visiting Istanbul over the last 20 years for conferences, recently for visits to refugee camps and most often now to see family living here. Istanbul is one of my favorite cities, full of heart, multiple cultures, history and citizens of intellect and warmth.

But recently the atmosphere has chilled. I’ve come on this trip to participate in the launch of Human Rights Watch’s 2016 World Report which focuses on the “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society” as causes that imperil citizens’ rights around the world. Istanbul was chosen as the launch city because it sits at the nexus of east and west, is the crossing point for millions of refugees fleeing the Syrian war and has an active civil society and free press that are now severely tested as the environment for rights deteriorates.

“Government-led restrictions on media freedom and freedom of expression in Turkey in 2015 went hand-in-hand with efforts to discredit the political opposition and prevent scrutiny of government policies in the run-up to the two general elections,” according to Human Rights Watch (HRW) 2016 World Report.

The restrictions include the investigation of Cumhuriyet newspaper for posting a report showing weapons on trucks allegedly headed to Syria. The paper’s editor Can Dϋndar and Ankara representative Erdem Gϋl were arrested and are now in jail awaiting trial. Other journalists have been arrested for criticizing the government. There have been police raids on media groups, a widespread firing of journalists perceived to be in opposition to the government, in particular to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Publisher Cevheri Gϋven of Nokta news magazine and editor Murat Çapan spent two months in jail for “inciting an armed insurrection against the government” for a report and a satirical picture of Erdoğan. Nokta’s website remains blocked by a court order. Months of pretrial detention have been handed out to those allegedly insulting Erdoğan via social media and during demonstrations.

I first came to Istanbul in spring, 1997 for the “Initiative for Freedom of Expression”, a conference that brought together PEN International and freedom of expression organizations in Europe to protest the harsh treatment of writers by the Turkish government and courts. Charges had been brought against the celebrated Turkish novelist Yaşar Kemal for an article he wrote for the German magazine Der Spiegel in which he accused the Turkish army of destroying Kurdish villages. Though he was acquitted, he is quoted as saying, “One person’s acquittal does not mean freedom of expression has arrived. You can’t have spring with only one flower. We still have to work very hard to achieve democracy in Turkey. I will continue to write these things until there are no trials against expression.” Kemal passed away last spring at age 91.

At the time activist and song writer Şanar Yurdatapan organized a publication that included Kemal’s essay and the writings of other Turkish and Kurdish writers who had been banned or imprisoned. He mobilized Turkish artists and publishers and academics to sign on as the publisher, and he asked writers from the more than 100 centers of PEN International around the world also to sign on as publisher. The publication thus challenged the government which would have to bring charges against hundreds of people as publisher. And so the Gathering for Freedom of Expression was born.

I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee during that time, and along with dozens of writers from around the world, I arrived in Istanbul for the conference. Şanar and his colleagues organized visits to prisons to try to see the many writers and publishers incarcerated, visits to courthouses to observe hearings and trials, a visit to the prosecutor’s office to insist that we too should be charged as publisher. We understood the embarrassment such would cause the government, though none of us aspired to go to a Turkish prison. The Initiative for Freedom of Expression held multiple press conferences because the only legal way to gather at that time was to have a press conference. Yaşar Kemal spoke at one of these.

There was also a freedom of expression conference called at a university where hundreds of students had mobilized in the campus square when we arrived. Many were protesting tuition hikes, not writers in prison, but the two gatherings merged. Riot police surrounded us all as we addressed the crowds.

The period of 1997 in Turkey was charged. The heavy hand of the State was palpable. The police were at every gathering. Cars followed us. In 1997 PEN International recorded more writers in prison or tangled in the judicial processes in Turkey than almost anywhere in the world except perhaps China.

But citizens were mobilizing and claiming space for expression. In the subsequent years the Initiative for Freedom of Expression and other freedom of expression and human rights organizations recorded regularly the abuses and circulated these and mobilized actions. Şanar was sent to prison because of his work and there studied the history and principles of civilian based resistance, practices he had instinctively employed. Every other year the Gathering for Freedom of Expression assembled in Istanbul, several of which I attended. Turkey could mark its progress by the decrease of the numbers of writers and publishers in prison. Until last year.

At the launch of HRW’s World Report this week, Şanar and I met again, smiling to see each other but not smiling about the state of affairs. Turkey appears to be reverting back to the ways and days of the 1990’s. Şanar has returned to song writing, still passionate, but addressing issues through music and advising (not quite on the sidelines) the next generation of activists.