Posts Tagged ‘Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’

Journey of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving—a favorite American holiday that includes everyone—reminds us to take time to give gratitude and to give. Though Thanksgiving has come and gone, the base of gratitude and the reminder to give in whatever way and fashion builds a foundation that endures and can outlast political, social and even climatic turmoil.

In this space and in this holiday season, I hope readers will share stories and thoughts on this theme. Gratitude and giving are the beginning and end of a redemptive journey.

London: Autumn Respite Around the Pond

A few years ago I penned a blog “Sounds of Summer” where I listened to the sounds of a summer afternoon. I let the politics and opinions and controversies of Washington, where I live, recede in my mind on the threshold of presidential elections, and I focused on the moments of nature and the wonders of a child’s summer world. I find myself wanting to retreat there more and more these days as the civic dialogue and political events seem harsher and less civil and downright mean.

In the last month I’ve had reason to travel to Beirut and London, where I considered events from a slightly different point of view, though no less fraught. The constant news coverage and the acrimony of the Kavanaugh Supreme Court hearings in the U.S. was replaced by the general uncertainty over refugees and the government in Beirut and by the angst over Brexit in London. While in Beirut, the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi broke in the news, and the horror of the unfolding tale of death and torture riveted attention in Washington and London as well. The possible political coverup currently brewing for this brutal violation of human rights remains the most troubling of all.

And yet for a moment—just an hour—in London yesterday I sat around the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens and allowed myself time to listen to the sounds and to witness life without a wider prism of consciousness and a larger world intruding.

On the crisp October morning the leaves stirred, still dusky green on the trees, not yet the vibrant reds and yellows of fall. Autumn arrived gently here in slight gusts of wind. A robust population of birds—elegant white long-necked swans, husky geese, green-faced mallards, plain brown ducks and a bevy of smaller birds cruised the water, circling the pond, eventually veering towards the edges where passersby tossed bread crumbs and seeds. A troupe of white seagulls swooped in for a landing on the water like trained hydroplaners and then just as abruptly and deftly took off for other parts of London.

At the far end of the pond sat Kensington Palace, quiet that day, home to the Duke and Duchess of Sussex—Prince Harry and his American bride Meghan Markle—who at the moment were in Australia, where they announced they’re having a baby.

People of all backgrounds circled the pond, dressed in slacks, jeans, dresses, light jackets, in hejabs and thwabs, children in strollers, young and old, sitting on the benches that ring the pond. School children in florescent green and yellow vests jogged by on a morning run.

Two elderly ladies and I increased our walking pace in a silent, unannounced race to the one empty bench at the bottom of the pond. I won, but they sat down beside me anyway, and we shared this coveted space where they talked quietly, and I wrote, and we watched this slice of morning.

A tiny dog trotted by as two stragglers panted past trying to catch up with their schoolmates. A couple stopped beside us and talked loudly on the phone in a language I didn’t recognize. In front of us a swan groomed herself, shaking off the water.

The grim headlines in the news: the possible failure of Brexit, the assassination and dismemberment of Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate, the US government’s closing of borders to a new convoy of migrants, the slippery commitment to truth for a moment receded on a blue sky London morning on the edge of autumn before the days grew short and dark.

A teacher with his final two lagging students jogged past, shouting, “Come on, guys…Let’s sprint to the finish! You can do this!”

Reluctantly I rose from the bench and left my fellow sojourners as I headed into the city for meetings and the work of the day.

Peace: Fabric with a Million Threads

Earlier this summer I had the opportunity to moderate a panel of high school teachers at the United States Institute of Peace called “A Year in the Life of a Peace Teacher.”

United States Institute of Peace in Washington, DC

On that morning of July 10 two positive news events broke: the final young soccer players and their coach, who had been trapped for almost two weeks, made it out of the caves in Thailand. And Liu Xia, wife of Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese Nobel Peace Laureate who died last year in custody, landed in Europe, released after a decade of virtual house arrest in China.

For me these events connected to the panel on the teaching of peace-building.

Was peace possible? Could peace be “built”? The answer we concluded that morning with cautious optimism was: Yes.

The miraculous rescue of the soccer team resulted because highly skilled citizens from nations around the world, including the U.S., Australia, Denmark, Britain, China and most importantly Thailand came together and exerted their best efforts with a common goal everyone agreed on.

Freedom for Liu Xia resulted in large part because citizens and politicians around the world spoke up and advocated on her behalf though a similar effort had not won the release of her husband.

That morning, listening to the teachers and their work with students reinforced a view that peace was not just building bridges between two opposing pylons or signing treaties, but was the weaving of hundreds, thousands, millions of threads, of each citizen taking responsibility within his/her own community.

Each year the U.S. Institute of Peace, founded in 1984 as a nonpartisan Institute to promote peace and resolution of conflicts around the world, also focuses on the U.S. and selects four high school teachers for year-long training which they take into their classrooms. They work on problem-solving and peace-building in their communities and also study global peace opportunities.

This year’s teachers from Missouri, Montana, Florida and Oklahoma shared ways they and their students ignited discussion in their classrooms and in their communities and then took initiatives relating to issues of race, immigration, etc. They emphasized the understanding that peace didn’t mean avoiding conflict but rather finding ways to engage nonviolently and then to find ways to resolve conflicts by listening, determining the interests of the other, showing empathy.

Specific stories of the teachers and their journeys with their students can be heard on this link.

To conclude the panel it was appropriate to quote Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo. In his career and in his final statement to the court before he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for his writing and work towards democracy, he told the judge: “I have no enemies and no hatred.” In his life Liu explained that to build a society without hate, one had to begin with one’s self. After he died in custody last year, many questioned whether he would have claimed this had he known his end, but those who knew him well said he would have because he believed the responsibility for a peaceful and fair society began with oneself.

Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people… It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, it can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.

It was poignant and fitting that day to see Liu Xiaobo’s wife Liu Xia’s smile as she landed in Helsinki.

Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

(Below is my talk for the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression, a conference held every two years, but this year it is being held via video May 26-27. For the first time in 21 years the organizers judged that a gathering in person was too problematic given the arrests and crackdowns on the media. Turkish presidential elections are scheduled for June 24 alongside parliamentary elections.)

I first visited Turkey for the inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” in March, 1997. At the time I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and joined 21 other writers from around the world. Along with over a thousand Turkish artists and writers, most of us had signed on to be “publishers” for Freedom of Thought, a book that re-issued writings which had violated Turkey’s laws against “insulting the State.” The book included work by noted authors, including celebrated novelist Yasar Kemal. None of us aspired to go to Turkish prison, but we understood the importance of showing up and showing solidarity with our Turkish colleagues. During that Gathering we visited prisons where writers and publishers were incarcerated and visited court rooms where they were charged.

Inaugural “Gathering in Istanbul” March 1997

In the subsequent decade, conditions for writers in Turkey improved. An amnesty released writers from prison; oppressive legislation was rescinded though new laws replaced old articles in the penal code. But the climate opened. We all took hope that Turkey might signal an opening of consciousness and an easing of political and legal constraints globally.

Unfortunately, that opening has closed, and we are here today on video because the biennial ‘Gathering in Istanbul’ for the first time in 21 years is too problematic to hold in Istanbul. The situation for freedom of expression is worse than ever in Turkey with more writers in prison than anywhere else in the world. Depending on the statistics of the day, there are more than 250 journalists and media workers in or facing prison terms, 200 media outlets closed, and thousands of academics and civil servants let go or facing charges.

Yet we are here, even if on video. And the organizers remain steadfast in Turkey. I take heart in the commitment of individuals who understand that freedom of expression is central to a free society and work towards that end.

For this “Gathering in Istanbul” it was suggested we look at “Freedom of Expression Around the World,” not just in Turkey. My general observation is that the world is reversing direction from those days 20 years ago when many thought authoritarianism was yielding globally to democracy and freedom.

The situation in my own country, the United States., is as fraught as it has ever been in my lifetime in the relationship between the government and the media, but the press is protected by the U.S. Constitution, laws, history and society. The majority of U.S. citizens still remain committed to protect freedom of expression and to remain vigilant though sometimes I fear we are preoccupied with our own challenges to the exclusion of more dire challenges to free expression around the world. I also fear we have lost credibility and impact when speaking out on these issues. Yet as an American, I can hold vigils in front of prisons, sit in courtrooms, write articles and books, meet Ministers, and then return home. I’m able to write and to speak out without being threatened with imprisonment or death.

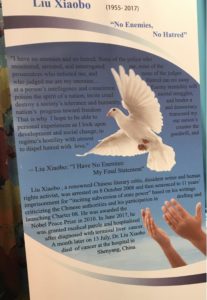

I’d like to focus the rest of my talk on the courageous writers in the Democracy Movement in China, especially after the death of Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Peace laureate who died last July in prison after serving nine years of an eleven-year sentence for “inciting subversion of state power” because of his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. I have the privilege of being an editor for the English-language edition of The Memorial Collection of Liu Xiaobo. The collection includes writings from dozens of Liu’s colleagues inside and outside China, who knew him and pay tribute to the man, his ideas and to the consequential voice he had in articulating and taking action on behalf of a free society.

One of the authors of Charter ’08, a document signed by hundreds of Chinese writers, intellectuals and citizens, Liu Xiaobo and others set out a democratic vision and path for China, using rule of law and consensus, not weapons and violence. It is individuals like Liu Xiaobo and his fellow Chinese writers and thinkers, who one hopes will eventually prevail. Like the writers and thinkers in Turkey, they are committed to ideas, to the rule of just laws and to nonviolent means to bring about change and wrest society from tyrannical modes.

Liu Xiaobo understood that a free society begins with the individual consciousness. In his Final Statement “I Have No Enemies” he addressed the court:

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people. It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to progress of our country to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

Such sentiment was difficult for many to accept, especially after he died. Many questioned whether he would have expressed the same sentiments had he known his end. I’ve been assured by those who knew him well that he would have stood by this statement. His commitment was rooted in his view of himself and of what it would take to change society.

A longtime colleague Cui Weiping has observed that Liu Xiaobo “…viewed the world through boundaries of his own making. Whatever he wouldn’t allow into his life, he was also unwilling to allow into the world. For instance, if he didn’t have violent tendencies in his own life, he would not let the behavior of others impose on him. If he valued freedom and autonomy, he would not become mired in hatred because of the crimes of others, since hateful people were dominated by the other side. If he experienced the good things and positive feelings of human life, he knew all the more that he must allow what was good and open to take root in himself and not what was biased and narrow-minded. His life was oriented toward love and light, not toward hatred and darkness. This was his own decision and what he was willing to take upon himself; every person writes his own history. Other people could choose to go along with Xiaobo or advance alongside of him, but there was no need to feel that this was his error or flaw that must be corrected or surmounted. Twenty years passed like a day, and he was a trailblazer for people who insisted on their own ideas. China lacks trailblazers like Xiaobo, and that is what allowed him to become a standard-bearer for the Chinese Democracy Movement and gain the widespread endorsement of the international community.”

A small number of Chinese writers drafted Charter 08, thousands of citizens have signed it, but only one went to prison and died.

No one knows and few can predict the success of Charter 08’s vision and the ultimate impact of Liu Xiaobo, but history has a long arc and may well bend to those who see our common humanity and the universal value of freedom for the individual. By focusing on the individual’s responsibility for his own behavior and consciousness, Liu offered the tools to empower all, for no government has the mandate over one’s individual consciousness. There the individual sets his or her own terms of engagement with the world.

In reading the essays of the many Chinese writers who knew and admired Liu Xiaobo and his vision, I also think of Turkish writers and artists I have had the privilege to know over the years who continue to work towards a free society.

The two countries and circumstances are different, and many would say Turkey is not as extreme as China, but in all the years I have been working with PEN, it was Turkey and China which placed the most writers under pressure. In China the sentences were often longer and harsher, but the numbers were greater in Turkey. But in both nations the individual voices of writers, publishers and artists continue to inspire.

Women’s Voices Rising

One hundred and nine years ago on February 28, 1909 the first National Woman’s Day was observed in New York where women protested against working conditions in the garment industry. The following year a conference of women from 17 countries met in Copenhagen and established Women’s Day, called for March 8 to promote equal rights, including suffrage for women. The next year on March 8, 1911 International Women’s Day brought over a million people to the streets in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, France and elsewhere to advocate for equal employment and wages and for the right to vote. In 1917 women in St Petersburg went on strike for “Bread and Peace,” demanding the end of World War I and the end to food shortages and the Czar. Four days later the Czar abdicated. Leon Trotsky wrote, “We did not imagine that this ‘Women’s Day’ would inaugurate the [Russian] revolution.” The gathering of women around the globe has continued over the last century with an abiding message that envisions each woman and girl being able to exercise her choices and participate without discrimination and fear in her society on an equal basis as men.

International Women’s Day demonstration in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1917. (Credit: Fototeca Gilardi/Getty Images)

In Lviv, Ukraine in mid-September, 2017, before #MeToo gained momentum in the U.S. and elsewhere, over 200 writers from 69 countries endorsed PEN International’s Women’s Manifesto (link and text below), a document that sets out principles, values and a vision for the times and for times ahead.

Delegates at PEN’s annual Congress, representing countries from every continent—men and women, Christian, Muslim, Jew, Buddhists, Hindi, atheist, multi-racial, multi lingual and politically diverse—voted for the document. PEN members do not always agree but are committed to freedom of expression and to the ideal of respect for human dignity and diversity. These are big words and big ideals and their interpretation is at times disputed among writers, who are often skeptical of words like “Manifesto.” But in the historic city of Lviv in the center of Europe’s own divide, they came together to affirm:

THE PEN INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MANIFESTO

The first and founding principle of the PEN Charter asserts that ‘literature knows no frontiers’. These frontiers were traditionally thought of as borders between countries and peoples. For many women in the world – and for almost all women until relatively recently – the first, and the last and perhaps the most powerful frontier was the door of the house she lived in: her parents’ or her husband’s home. For women to have free speech, the right to read, the right to write, they need to have the right to roam physically, socially and intellectually. There are few social systems that do not regard with hostility a woman who walks by herself.

PEN believes that violence against women, in all its many forms, both within the walls of a home or in the public sphere, creates dangerous forms of censorship. Across the globe, culture, religion and tradition are repeatedly valued above human rights and are used as arguments to encourage or defend harm against women and girls.

PEN believes that the act of silencing a person is to deny their existence. It is a kind of death. Humanity is both wanting and bereft without the full and free expression of women’s creativity and knowledge.

PEN ENDORSES THE FOLLOWING INTERNATIONALLY RECOGNISED PRINCIPLES:

- NON-VIOLENCE: End violence against women and girls in all of its forms, including legal, physical, sexual, psychological, verbal and digital; promote an environment in which women and girls can express themselves freely, and ensure that all gender-based violence is comprehensively investigated and punished, and compensation provided for victims.

- SAFETY: Protect women writers and journalists and combat impunity for violent acts and harassment committed against women writers and journalists in the world and online.

- EDUCATION: Eliminate gender disparity at all levels of education by promoting full access to quality education for all women and girls, and ensuring that women can fully exercise their education rights to read and write.

- EQUALITY: Ensure that women are accorded equality with men before the law; condemn discrimination against women in all its forms and take all necessary steps to eliminate discrimination and ensure the full equality of all people through the development and advancement of women writers.

- ACCESS: Ensure that women are given the same access to the full range of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights to enable the full and free participation and public recognition of women in all media and across the spectrum of literary forms. Additionally, ensure equal access for women and girls to all forms of media as a means of freedom of expression.

- PARITY: Promote the equal economic participation of women writers, and ensure that women writers and journalists are employed and paid on equal terms to men without any discrimination.

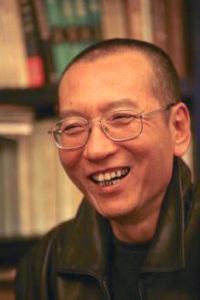

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo died this past July in prison, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for his role in drafting Charter ’08 calling for democratic reform in China. Below is my essay in The Memorial Collection for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, just published by the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition and Democratic China.

I never met Liu Xiaobo, but his words and life touch and inspire me. His ideas live beyond his physical body though I am among the many who wish he survived to help develop and lead democratic reform in China, a nation and people he was devoted to.

Liu’s Final Statement: I Have No Enemies delivered December 23, 2009 to the judge sentencing him stands beside important texts which inspire and help frame society as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail did in my country. King addressed fellow clergymen and also his prosecutors, judges and the citizens of America in its struggle to realize a more perfect democracy.

I hesitate to project too much onto Liu Xiaobo, this man I never met, but as a writer and an activist through PEN on behalf of writers whose words set the powers of state against them, I can offer my own context and measurement.

Liu said June, 1989 was a turning point in his life as he returned to China to join the protests of the democracy movement. In June, 1989 I was President of PEN Center USA West. It was a tumultuous year in which the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was issued in February, and PEN, including our center, mobilized worldwide in protest.

In May, 1989 I was a delegate to the PEN Congress in Maastricht, Netherlands where PEN Center USA West presented to the Assembly of Delegates a resolution on behalf of imprisoned writers in China, including Wei Jingsheng, and called on the Chinese government to release them. The Chinese delegation, which represented the government’s perspective more than PEN’s, argued against the resolution. Poet Bei Dao, who was a guest of the Congress, stood and defended our resolution with Taipei PEN translating.

When the events of Tiananmen Square erupted a few weeks later, my first concern was whether Bei Dao was safe. It turns out he had not yet returned to China and never did. PEN Center USA West, along with PEN Centers around the world, began going through the names of Chinese writers taken into custody so we might intervene. I remember well reading through these names written in Chinese sent from PEN’s London headquarters and trying to sort them and get them translated. Liu Xiaobo, I am certain must have been among them, though I didn’t know him at the time.

In his Final Statement to the Court twenty years later, Liu told the consequence for him of being found guilty of “the crime of spreading and inciting counterrevolution” at the Tiananmen protest: “I found myself separate from my beloved lectern and no longer able to publish my writing or give public talks inside China. Merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his right to teach, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual could no longer speak openly. Whether we view this as my own fate or as the fate of a China after thirty years of ‘reform and opening,’ it is truly a sad fate.”

I finally did meet Wei Jingsheng after years of working on his case. He was released and came to the United States where we shared a meal together at the Old Ebbit Grill in Washington. I was hopeful I might someday also get to meet Liu Xiaobo, or if not meet him physically, at least get to hear more from him through his poetry and prose.

His words are now our only meeting place. His writing is robust and full of truth about the human spirit, individually and collectively as citizens form the body politic. I expect that both his poetry and the famed Charter 08, for which he was one of the primary drafters and which more than 2000 Chinese citizens endorsed, will resonate and grow in consequence.

Charter 08 set out a path to a more democratic China which I hope one day will be realized.

“The political reality, which is plain for anyone to see, is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government,” noted Charter 08. “The ruling elite continues to cling to its authoritarian power and fights off any move toward political change….

“Accordingly, and in a spirit of this duty as responsible and constructive citizens, we offer the following recommendations on national governance, citizens’ rights, and social development: a New Constitution…Separation of Powers…Legislative Democracy…an Independent Judiciary…Public Control of Public Servants…Guarantee of Human Rights…Election of Public Officials…Rural—Urban Equality…Freedom to Form Groups…Freedom to Assemble…Freedom of Expression…Freedom of Religion…Civic Education…Protection of Private Property…Financial and Tax Reform…Social Security…Protection of the Environment…a Federated Republic…Truth in Reconciliation.”

Charter 08 addresses the body politic. Liu Xiaobo’s Final Statement: I Have No Hatred addresses the individual, and for me resonates most profoundly. Its call doesn’t depend on others but on oneself for execution. He warned against hatred.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows). It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

At a recent conference a participant asked if Liu Xiaobo might have changed this statement if he understood how his life would end. A friend who knew him assured that he would not for he was committed to the idea. Liu Xiaobo’s commitment to No Enemies, No Hatred does not accede to the authoritarianism he opposed, but instead resists the negative. He aligns with benevolence and love as the power that nourishes the human spirit and ultimately allows it to flourish. Liu’s words and his ideas lived offer us all a beacon and a guide.

Thanksgiving: History and Healing in Troubled Times

In the U.S. Thanksgiving is a favorite holiday, a time when family and friends come together, pause in their hectic, perhaps fraught, lives to give thanks and consider their blessings. Gratitude remains a most reliable platform upon which to build the future.

My own gratitude includes my loving family. In a break with my monthly blog, I’d like to share a moving Thanksgiving essay by my son Elliot, published in The New York Times: A Thanksgiving Message in a 1963 Proclamation.

Chatham House Rule and Other Civilities

Last week I participated in a number of forums operating under the Chatham House Rule—a large dinner in Washington with experts on Afghanistan, another in New York focused on the United Nations, panel discussions on North Korea, Myanmar, Ukraine and Iraq and a full day meeting focused on troubled spots around the globe attended by former prime ministers, foreign ministers, ex-military officials and experts.

What struck me in this compressed tour of world conflicts was the civility and richness of the discussions which wrestled with problem-solving compared to the public discourse these days that sometimes seems reminiscent of a high school lunchroom.

In a meeting held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use information, but the identity and affiliation of the speakers are confidential. The purpose of the rule, first established in 1927 at Chatham House: The Royal Institute of International Affairs in London, is to encourage openness and the sharing of information. Anonymity is not to encourage personal gossip and rumor.

No problems were solved in last week’s meetings, but analysis from multiple points of view, which were not always in agreement, were debated and iterated. Issues, not personalities held the focus. To the extent personalities framed the problem, steps towards engagement or containment were set on the table.

Throughout the discussions, I recalled Albert Einstein’s counsel: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking that created them.” It is a challenge to think outside traditional corridors of thought and even more challenging when respect for ideas is subsumed by attacks on people.

Many of today’s conflicts spring at least in part from the politics of identity—be that identity defined by religion, political party, gender, race or nationality. The aggregating principal of nations appears to be fragmenting in many areas of the world with authority breaking down or hardening into authoritarianism.

There never have been easy solutions for mankind living together, but the Chatham House Rule offers at least a momentary space for ideas to cross borders and barriers before being shot down.

“Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

The train from Copenhagen airport to Malmö, Sweden took just half an hour across the 21st century Øresund Bridge, which spans five miles of water, then the train dove into 2.5 miles of tunnel. Looking out the window at farmland and the blue waters of the Baltic Sea, I imagined this journey was not so easy 74 years ago with Nazis in pursuit. In 1943 as the Nazis went to sweep Denmark’s 7800 Jews into concentration camps, Danish and Swedish citizens rallied, and 7220 people managed to escape in boats across this Sound to nearby Sweden. Thousands landed in Malmö where I was headed for a less dramatic, but still fraught, occasion.

Members of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) whose writers live inside and outside mainland China were joining writers from Uyghur PEN, Tibetan PEN and members from Inner Mongolia, along with writers from PEN Turkey and Azerbaijan for the First International Conference of Four-PEN Platform: “Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred.” Swedish PEN was providing the safe space for debate, discussion and strategies of action on human rights and freedom of expression. Just six weeks before, one of ICPC’s founding members and honorary President Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo, died in a Chinese prison after serving nine years of an 11-year sentence for drafting Charter 08, a document co-signed by 308 writers and intellectuals calling for a more democratic and free China.

A recognized leader in China’s Democracy Movement, Liu Xiaobo’s loss was deeply felt. A number of the writers gathered knew and worked with Liu. Most knew at least one fellow writer in prison. Many now live in exile themselves. Almost half of PEN International’s writers-in-prison cases are located in the regions represented at the conference.

The theme “No Enemies, No Hatred”—drawn from Liu Xiaobo’s final statement at his trial—sparked the debate in Malmö.

Keynote speaker Nobel Laureate Shirin Ebadi challenged, “But I do have enemies and I do feel hatred.” Facing death threats from her government in Iran, she had to leave everything behind at age 63 and move to London.

“Liu Xiaobo said he had no hatred and no enemies, but he also never compromised with any dictators,” she noted. “We must fight against dictators but our weapons are our pens and are nonviolent. We must not be silent. We can’t compromise with governments such as China who would eradicate an ‘empty chair’ from the internet.” [When Liu Xiaobo was unable to attend the Nobel ceremony because he was in prison, the Nobel Committee placed an empty chair on stage to represent him. The Chinese government is said to have censored the term “empty chair” from the internet in China.]

“What is the use of a pen if Liu Xiaobo is dead?” challenged one writer. Another speculated that if Liu Xiaobo had known how his life would end, he would have changed his message. A friend of Liu’s assured that he would not because for him no enemies and no hatred was a spiritual commitment.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows),” Liu declared to the court at his trial. “It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy…. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate…. No force can block the thirst for freedom that lies within human nature, and some day China, too, will be a nation of laws where human rights are paramount.”

Within this frame and this hope, stories of persecution were exchanged among the Tibetan, Uyghur and Mongolian writers in China and among writers from Azerbaijan and Turkey, where over 150 writers and journalists are currently in prison and over 100,000 judges, academics and civil servants have been fired.

Uyghur and Mongolian writers noted that starting September 1 the Uyghur language is banned from all schools.

“The Chinese call all Uyghurs terrorists,” said one participant. “I have never seen a gun or a bomb in my life, but my name is on Interpol’s list because of my pen. I am a German citizen, and I was in Italy, invited by the Italian Senate when Italian police arrested me because the Chinese government put me on a terrorist list because I speak out for the Uyghurs.”

Can one operate against totalitarian, oppressive governments without hatred and enemies? The question remained unresolved, but participants agreed that protest and actions needed to remain nonviolent. To amplify the voices of the writers who were in prison, those outside could publish them, protest to their governments and recognize the writers with awards. Implicit was a belief in the power of culture and ideas to ultimately change society.

The 2016 Liu Xiaobo Courage to Write Award was given at the conference to Hu Shigen and Mahvash Sabet. Writer and lecturer Hu Shigen spent his career in the Democracy Movement since 1989 Tiananmen Square when he was arrested for “counterrevolutionary propaganda” and sentenced to 20 years in prison and after release was arrested again for “subverting state power” and returned for seven and a half years in prison where he still resides. Mahvash Sabet, a teacher and noted Baha’i poet, was detained for her faith and for “acting against the security of the country and corruption on earth” in Iran and is now serving a 20-year sentence in Evin prison in Tehran. Her friend Shirin Ebadi accepted the award on her behalf.

Other cases highlighted by the conference included Ilham Tohti, Nurmuhemmet Yasin, Gulmire Imin, Memetjan Abdulla, Gheyret Niyaz, Zhao Haitong, Omerjan Hasan, Qin Yongmin, Zhang Haitao, and Mehman Aliyev. The gathering also highlighted the situation of Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo’s wife, who is believed still under house arrest. Many are working in the hope of getting her out of China.

When Shirin Ebadi was presented a statue of Liu Xiaobo, she noted that it would sit beside a statue she’d been given of Martin Luther King.

Dr. King’s writing of 54 years ago in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” read at the closing demonstrated the power of ideas and words to endure long after their author has passed away: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Dogs, Cows and Wolves: Security on the Golan Heights

On the Golan Heights in the hills separating Syria and Israel fields of cows graze and sleep, swishing their tails, whisking off flies. Many of the cows lying in the fields appear to be waiting and contemplating as cows do. The cows are a source of milk and of meat and income for a kibbutz nearby. Among the cows wander white dogs. It is a peaceful scene except for the distant thudding and booming of the war in Syria just a mile away.

But at night wolves come out. The dogs and an occasional cowboy are the cows’ main defense. The wolves need to eat too, and a cow just standing there, especially if separated from the herd, is a natural target. The wolves are sleek and fast, and the cowboys respect them.

Sometimes the wolves score, but more often the dogs bark and circle, and the cows bellow. Dogs and cows together hold their own, and the wolves have to look elsewhere for food. Twenty years ago the cowboys determined that if they placed pups in with the cows from birth until they were 10 months old, the dogs would naturally identify with and want to protect the cows. If there are enough dogs, they can dissuade the wolves. The scheme seems to be working, but it is a standoff and not the same as peaceful coexistence.

This drama has played out with theme and variation over the past 50 years since the Golan Heights were occupied by Israel after the Six-Day War in 1967. Israel’s offer to return the Golan in exchange for peace with Syria was rejected then, and Syria attacked in the 1973 Yom Kippur war and was defeated. At present Israel occupies two-thirds of the hills of the Golan which overlooks the Jordan Rift Valley and contains the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River. The Golan includes volcanic fields with dark volcanic rock and lighter limestone rocks. Fruit trees, particularly apples, grow there. The area overlooks Israel which sees the Golan as a natural defense line that secures its border with Syria. Between the two countries lies a small demilitarized zone monitored by the United Nations.

As the Syrian war turns yet another corner with the recent ceasefire, the Russians (and potentially by association Hezbollah and the Iranians) are now sanctioned to patrol and come within a mile of the Israeli border. Tension is again heightening. The border itself is protected by small fences and bunkers, but now on higher alert by the Israeli Army and those in the Reserves who tend the cows and pick the apples in times of peace.