Posts Tagged ‘Wole Soyinka’

PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest

I begin with the memories…

Castle Rock and Edinburgh Castle in Edinburgh, Scotland

—the imposing walls around Castle Rock which stands above the city of Edinburgh and dates back to the Iron Age,

—the 12th century castle/fortress inside,

—the Old Parliament building,

—the New Parliament building where we sat in high-backed theater-style seats in an arena,

—the dorm room residence inside Pollack Halls where we stayed at Edinburgh University near the city center, beside an extinct volcano,

—the receptions at Parliament House and Signet Library and the City Arts Center where there was never quite enough food for the overly hungry delegates who descended upon the platters,

—the UNESCO seminars on women and literature, including my paper The Power of Penelope,

—and elections, so many elections and speeches—three candidates for Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair, seven candidates for International PEN President, nine Ad Hoc Committee members as precursors to a new governing board for International PEN.

These were the first contested elections I remembered in International PEN. A wider democracy was spreading with ballots and speeches. I also remember the tension and the occasional flares of anger, and the effort to hold us all together and ultimately the confident results and the determination to move forward in unity. International PEN President Ronald Harwood warned that while PEN badly needed to democratize “power” so it wasn’t too centralized, residing in the hands of a few, the delegates should not make the struggle personal and should go forward with a sense of humor. We were an organization of writers, not the government of the world, he admonished, warning members not to confuse bureaucracy with democracy.

—I remember the trip to Glasgow where a few of us had a stimulating visit and tea at the home of James Kelman (Booker Prize winner How Late It Was, How Late) who had been with us in the protests in Turkey a few months before (see PEN Journey 19) and the old Mercedes tucked in the garage in the working class neighborhood.

—And the Edinburgh International Festival, including the Edinburgh Book Festival, happening simultaneously all around us.

—And finally the exquisite August light in Scotland.

Program for 1997 PEN International Congress

I begin with memory then plunge into the minutes and documents of the 64th PEN Congress August, 1997 when delegates from 77 PEN centers around the world gathered. The Congress theme Identity and Diversity posed the questions:

In the contemporary world there are intense pressures, political or commercial, deliberate or unconscious, towards an imposed uniformity. One example is the effect on language. Indigenous languages, which embody particular traditions and experience, are in many countries under threat of displacement and extinction. These tendencies are inimical to literature which depends on its local personality for its color and effectiveness even when it achieves universal significance.

On the other hand, we live in an inter-dependent world where peace, prosperity and ultimately even survival, require co-operation. This international co-operation may be assisted by the use of a few languages which are widely understood. International exchange of the appropriate kind can also bring cultural enrichment.

How can these apparently contradictory objectives of diversity and co-operation be reconciled? Does literature have a role in this respect?

As with most abstract themes and questions, there is no simple answer, but the theme was a pivot, in this case both in the literary sessions and inadvertently in the business of PEN as the organization sought to restructure itself. Because this was my last congress as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, the work of that Committee absorbed my focus. My two reports—one the official printed International PEN Writers in Prison Committee report and the other an address to the Congress—observed, and in a fashion related, to this theme:

[Written report:]

PEN Writers in Prison Committee Report, 1997

Tension between the individual and the state underlies the work of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In some countries constitutions and governing principles are set out to protect the individual from the state, but in the majority of countries which PEN monitors where writers are imprisoned, threatened or killed, the state is organized to protect itself from the individual. Whether those countries be totalitarian regimes like China, Myanmar/Burma, Syria, Vietnam, Cuba or democracies like Turkey and South Korea, when the state holds itself superior to the rights of its individual citizens, freedom of expression is seen as a threat to stability rather than a sign of stability.

In 1997 the Writers in Prison Committee has defended individual writers in at least as many of the new and older democracies around the world as in totalitarian states. Since 1990 dozens of nations in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia have restored or initiated multi-party democratic elections. The turn to the democratic process initially freed up restrictions on writers and journalists in many countries. However, after the first flush of these freedoms, after dozens of independent publications sprang up in Argentina, Belarus, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Russia, Sierra Leone, Zambia, etc., tensions mounted between the individual voice and the state. Restrictions and press laws followed, and writers once again found themselves facing prison terms on such charges as “insulting the President”, “writing derogatory statements against the government and government officials”, and “seditious libel.”

In some states like Sierra Leone harsh restrictions on the media preceded coups and the loss of democracy. Reporting restrictions and brief detentions of journalists enforced by the crumbling Mobutu government in Zaire (now Congo), did not serve to protect it from its eventual collapse. Earlier this year the political crackdown in Belarus was preceded by severe censorship and curtailment of publications. The collapse of the government in Albania was followed by severe restrictions on publications and attacks and death threats on journalists and writers.

When a coup occurs and democracy fails, the consequences for free expression are usually disastrous as has been seen in Nigeria where journalists continue to serve lengthy prison terms and are arbitrarily detained, sometimes for months without charge. Another instance of a threat to freedom of expression in Nigeria is that of PEN member and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka who is among 12 dissidents charged in Nigeria this year with the capital offense of treason. Soyinka remains free outside the country but is certain to be imprisoned if he returns.

Pressure on writers and the media continued or increased in many new and old democracies, including Algeria, Argentina, Bosnia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgystan, Mexico, the Palestinian authority, Turkey, Uganda and Zambia. Pressures took the form of legislation which required publications to obtain government licenses and approval and/or required journalists to have state-approved credentials. Pressure also took the form of arrest, arbitrary detention and death threats…

When democracy fails, there are hosts of reasons embedded in history and politics. Curtailment of free expression is not necessarily the precipitating cause, and curtailment of free expression does not always lead to failure of democracy. However, repression of the written word and of the writer remains at the very least a symptom and often a warning light that political failure lies ahead…

The report goes on to outline situations of individuals under threat. Reading these reports is reading a political history of the time, told through the circumstances of individual writers. One of the highlighted cases at the Congress in 1997 was that of Iranian writer Faraj Sarkohi who’d signed a petition calling for freedom of expression, along with 134 other Iranian writers. Sarkohi had been kidnapped by the Iranian secret service while on his way to visit family in Germany; he was tortured and threatened with execution. Because of the worldwide protests by PEN and others, he was eventually released the following year and sent into exile.

Visiting the WiPC meeting in Edinburgh, Egyptian professor Nasr Hamed Abu-Zeid, a leading liberal theologian on Islam, told his story of being declared an apostate for his research and forced to divorce his wife, also an academic. They had fled Egypt where apostates could be killed. Şanar Yurdatapan, the Turkish activist who’d organized the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression which many of us attended earlier that spring, had just been released from prison and also spoke to the meeting. The cases of Sarkohi and Abu-Zeid and Şanar were among 700 on the WiPC records.

[Address to Assembly of Delegates:]

After four years chairing International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, I’ve come to appreciate the simplicity of the Committee’s mandate and the complexity of its execution. To defend the individual’s right to free expression is to defend not only the essence of literature but also a cornerstone of free society. Our defense begins with the individual writer, but inevitably we are caught in the movements of politics and history where individuals struggle to shape, divert or oppose the tides. One of the most significant developments in the past few years has been the expansion of multi-party democracies across the globe, a development that at first glance would signal progress for free expression. However, from our work we have seen that democracy takes more than a polling booth and a list of candidates on a ballot to come to fulfillment. Freedom of the written word is essential for a democracy to work over the long term, and attacks on this freedom usually foreshadow larger repression and even the failure of the democracy itself.

This year PEN has seen repressive laws enacted and/or writers arrested and killed in the new and old democracies of Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Belarus, Bosnia, Cambodia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Russia, Palestinian territory, Peru, Sierra Leone, South Korea, Turkey, Zambia. Many governments have passed or tried to pass laws to bring publications under their control through licensing and government-approved credentials. These laws have been followed by the arrest of writers.

Repression remains the most severe in totalitarian states such as China, Cuba, Iran, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Syria, Vietnam. China continues to imprison more writers for longer periods of time—over 70 individuals, many serving 10-20 years—than any other country. Many of the writers who were imprisoned during Tiananmen Square have been released in the past two years, but others have taken their place. The Writers in Prison Committee is watching with great concern legislation which could lead to restrictions on writers in Hong Kong as China takes over. The Committee is also following closely the continued repression in Myanmar (Burma) where prison conditions remain harsh and at least 25 writers remain behind bars, many with sentences exceeding ten years…

Many of the cases in Africa this year came from new democracies struggling with issues of free expression, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Zambia. The military dictatorship of Sani Abacha in Nigeria continued to occupy the focus of many PEN centres who worked on behalf of writers still in prison. Protests from a number of PEN centres assisted in the release of two Nigerian writers…Our Committee heard a statement from PEN main case Koigi wa Wamwere from Kenya, where riots have broken out after calls for democratic reform. Centres around the world have lobbied for his release, and he is now out on medical bail, and the Writers in Prison Committee has assisted his return to Norway where he is living. He sent a message thanking PEN for its work on his behalf. He writes, “When dictators arrest writers, they guard them with more guns and soldiers than they guard enemy armies in captivity. Dictators fear ideas and writers more than they fear guerrilla armies. Afterall they know that without ideas even guerrilla armies would wither away and die…”

In Latin America PEN continued to protest this year the imprisonment and detention of writers in Cuba. This spring the Writers in Prison Committee issued its report on its Cuba trip last fall, focusing on dissident writers who often had to choose between prison and exile…In Peru, though legislative and judicial reforms have occurred in the last years, at least 11 writers there have reported threats and/or attacks from both governmental and non-governmental sources, and sixty writers and journalists have reported death threats or attacks in Argentina…

The Writers in Prison Committee continues to work closely with freedom of expression organizations around the world, sharing our research and disseminating via the internet so that when a writer is arrested as far away as Tonga, the King of Tonga suddenly found himself receiving faxes from all over the world.

Over the years the political tides have shifted, but members’ work on behalf of individuals and the friendship of writer to writer remain even after the writers are released. This year we saw releases in Cameroon, China, Cote d’Ivoire, Cuba, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Kuwait, Maldives, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Peru, and Russia. On occasions we have gotten to meet and know the individuals personally. This year when the Nigerian government picked up Ladi Olorunyomi, the Writers in Prison Committee was quickly alerted. A number of us had had the opportunity to meet with her husband Dapo, a prominent editor and dissident now living in exile in the United States. Isabelle Stockton, our Africa researcher and I spoke in the morning, and she called him to gather more details. When I phoned him later in the day, he said, “I was going to call you, but before I could, PEN was already calling me.” As soon as we determined that Ladi Olorunyomi had not been charged with a crime, had no access to lawyers and was not allowed to see her family, we put out a Rapid Action to our centres and shared the information with other freedom of expression organizations all around the globe. During her almost two months in captivity we were able to monitor the case, share information, and hear with great relief when this writer and mother was finally released.

Dapo, who had secretly fled Nigeria a year earlier lest he be imprisoned, wrote PEN, “Thank you for everything! I am very grateful, but I lack the words, appropriate enough to convey my gratitude…to our good friends at PEN International.”

The business of PEN throughout the year and at the annual Congress also included the work of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women’s Committee, Peace Committee, the growing activity of the Exile Network and the literary sessions. The UNESCO seminars on Women’s Cultural Identity linked to the seminars on Literature and Democracy at the Guadalajara Congress the year before. In many parts of the world women still did not have full democratic rights. Significantly, in Latin America only 10% of books published were by women, and in Africa it was as few as 2%. But I must leave others to elaborate these activities.

At the 64th Congress results of the many elections yielded the next group of leaders who would take the organization into the last years of the 20th Century and into the transformation of governance. At the Congress Ronald Harwood was elected a Vice President as I had been at the previous Congress and as such we stayed connected and in the wings for the changes ahead.

Election results of the 64th PEN Congress:

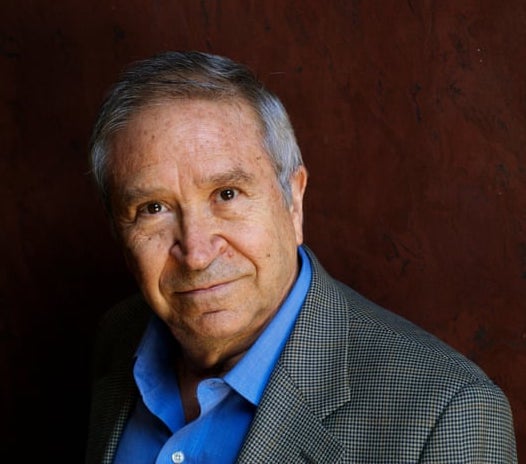

Homero Aridjis

Seven candidates stood for the presidency from Europe, Africa and the Americas though one dropped out. Homero Aridjis of Mexico, well-known poet, journalist and diplomat, was elected the next President of International PEN.

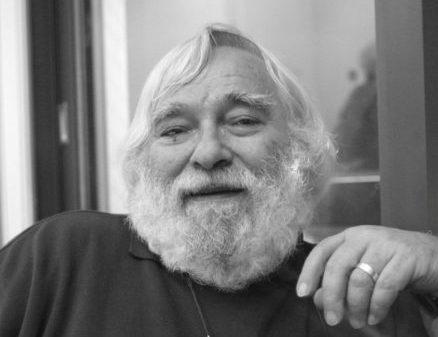

Moris Farhi

Novelist Moris Farhi, former chair of English PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, was elected chair of the WiPC. The two runner-ups Louise Gareau-Des Bois (Quebec PEN) and Marian Botsford Fraser (PEN Canada) agreed to serve for a year as Vice Chairs. In 2009 Marian Botsford Fraser was elected chair of WiPC and served till 2015.

The new Ad Hoc Committee elected at the Congress included Marian Botsford Fraser (Canada), Takashi Moriyama (Japan), Boris Novak (Slovenia), Carles Torner (Catalonia), Jacob Gammelgaard (Denmark), Vincent Magombe (Africa Writers Abroad), Gloria Guardia (Colombia), Gordon McLauchlan (New Zealand) and Monika van Paemel (Belgium). This committee was charged with considering all the restructuring proposals and preparing a draft for discussion and adoption by the Assembly of /Delegates at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. The Ad Hoc Committee was also tasked as a Nominating Committee to search for a new International Secretary. Alexander Blokh, re-elected for another year as International Secretary, planned to step down at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. Little did I know nor aspire to take on that role six years later.

New PEN Centers voted in at the Edinburgh Congress included Cuban Writers in Exile, Somali-speaking Center, Sardinian PEN Center, and a reconstituted Mexican PEN Center.

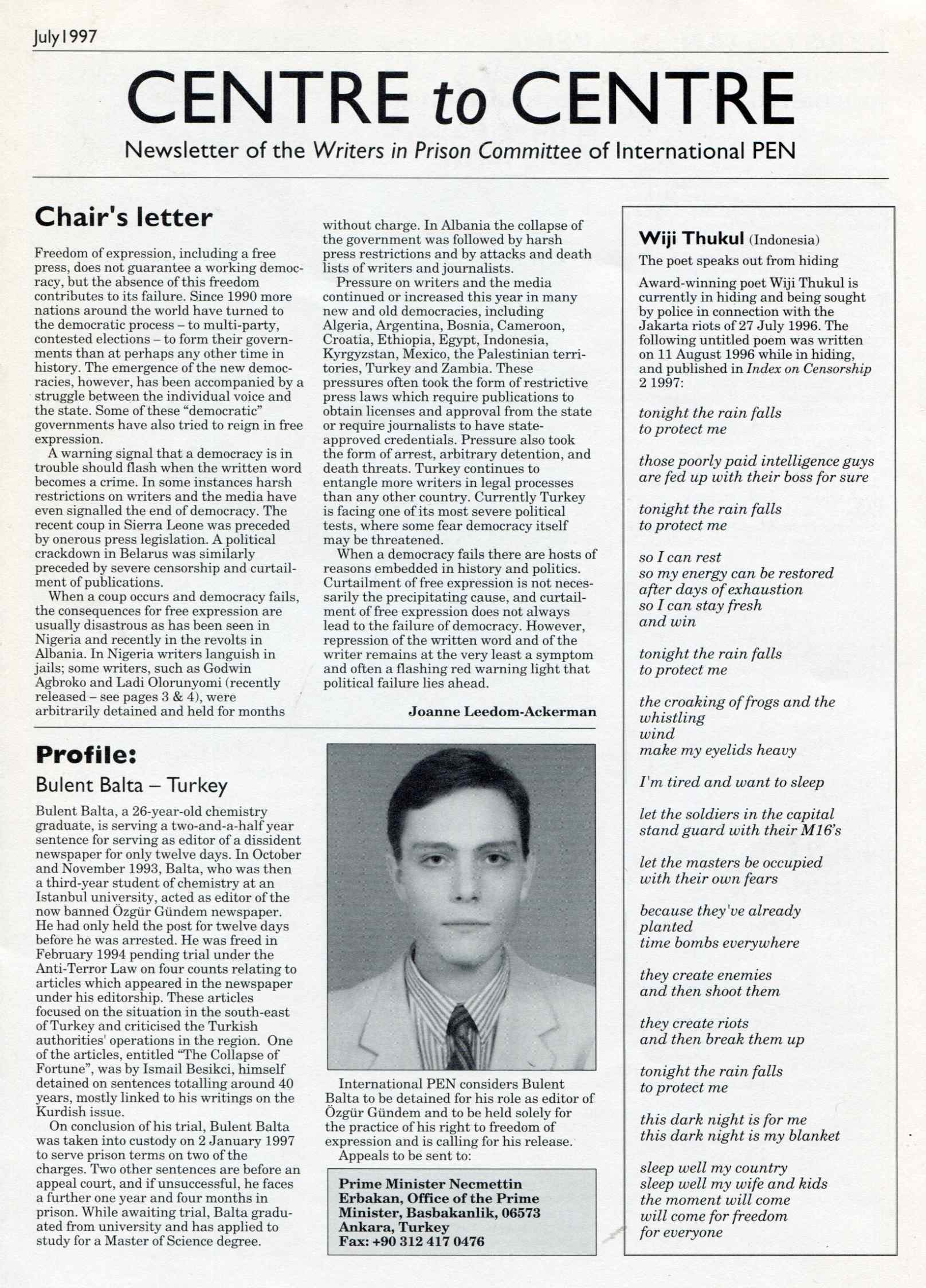

PEN International’s Writer in Prison Centre to Centre newsletter, July, 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 21: Helsinki–PEN Reshapes Itself

PEN Journey 15: Speaking Out: Death and Life

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

As I wrote holiday cards for the prisoners on PEN’s list this year, I recalled the many cases of writers PEN has worked for over the decades—the successes when writers were released early from prison and the sorrow when they did not survive. The path back for a writer imprisoned for his work is rarely easy, at times has led to exile, but often is accompanied by a mailbag full of cards and letters from fellow writers around the world.

I also sat with PEN’s Centre to Centre newsletters spread around me from 1994-1997, the years I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). During that period if a country was mentioned, I knew whether writers were imprisoned there and often knew the main cases as did PEN’s researchers. At the time we published twice a year PEN’s list with brief descriptions of the cases. Proofing paragraph after paragraph of hundreds of situations, I would know without looking when I had moved from one country to another by the punishments given. Lengthy prison terms up to 20 years to life meant I was reading cases from China, but if the writers were suddenly killed either by government or others, I’d moved on to Columbia. In Turkey were pages and pages of arbitrary detentions and investigations and writers rotating in and out of prison.

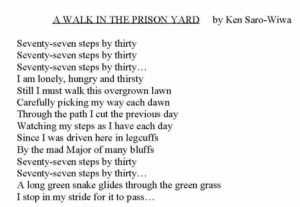

Names from this period are a kind of ghost family for me, evoking people and a time and place: Taslima Nasrin, Fikret Başkaya, Mohamed Nasheed, Gao Yu, Bao Tong, Hwang Dae-Kwon, Myrna Mack, Ma Thida, Yndamiro Restano, Mansur Rajih, Luis Grave de Peralta, Brigadier General José Gallardo Rodríguez, Koigi wa Wamwere, Eskinder Nega, Tefera Asmare, Liao Yiwu, Ferhat Tepe, Dr. Haluk Gerger, Ayşe Nur Zarakolu, Ünsal Öztürk, İsmail Beşikçi, Eşber Yağmurdereli, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Đoàn Viết Hoạt, Nguyễn Văn Thuận, Balqis Hafez Fadhil, Tong Yi, Christine Anyanwu, Tahar Djaout, Aung San Suu Kyi, Yaşar Kemal, Alexander Nikitin, Faraj Sarkohi, Ali Sa’idi Sirjani, Wei Jingsheng, Chen Ziming, Slavamir Adamovich, Bülent Balta, and many more. Many are now released, a few are even working with PEN, a number have deceased and two of the most celebrated and tragic—Liu Xiaobo and Ken Saro-Wiwa—were executed, one left to die in prison, the other hung.

Page 1 of PEN International’s campaign for Ken Saro-Wiwa 1994-1996

In their cases, no amount of mail or faxes or later emails or personal meetings with ambassadors and diplomats changed the course for these writers. A year before Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death, noted Iranian novelist Ali Sa’idi Sirjani died in prison. And years later the murder of Anna Politkovskaya in Russia and the murder of Hrant Dink in Turkey and in 2017 the death in prison of Chinese poet and Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo all stand out as main cases where PEN and others organized globally but were unable to change the course. I’ll address the case of Liu Xiaobo in a subsequent blog. He was also in prison during the 1990’s but was not yet the global name and force he became.

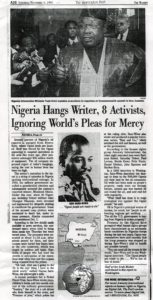

One of the most noted of PEN’s cases in the mid 1990s was Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa who was hanged November 10, 1995. Ken understood they would hang him, but PEN members did not accept this. Ken was an award-winning playwright, television producer and environmental activist who took on the government of Nigerian President Sani Abacha and Shell Oil on behalf of the Ogoni people whose land was rich in oil and also in pollution and whose people received little of the profits.

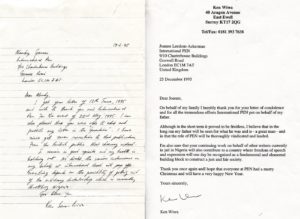

I was living in London when Ken Saro-Wiwa, who had been arrested before for his writing and activism, visited PEN and other organizations in support of the Ogoni cause. PEN took no position on political causes but campaigned for his freedom to write and speak without threat. He met at length with PEN’s researcher Mandy Garner, providing her books and documentation of how he was being harassed in case he was arrested again. When he returned to Nigeria, he was arrested again and imprisoned in May 1994, along with eight others, and charged with masterminding the murder of Ogoni chiefs who were killed in a crowd at a pro-government meeting. The charge carried the death penalty.

PEN mobilized quickly and stayed in close contact with his family. Mandy worked tirelessly on the case, gathering and coordinating information and actions. Ken Saro-Wiwa was an honorary member of PEN centers in the US, England, Canada, Kenya, South Africa, Netherlands, and Sweden so these centers were particularly active, contacting their diplomats and government officials. At PEN International we met with members of the Nigeria High Commission; novelist William Boyd joined the delegation. “I remember sitting opposite all these guys in sunglasses wearing Rolex watches, spouting the government line,” Mandy recalls. We also talked with ambassadors, including from England, the US and Norway to encourage their petitioning of the Abacha government. We met with Shell Oil officials to ask that they intervene to save Ken Saro-Wiwa’s life. PEN USA West also had lengthy meetings and negotiations with Shell Oil. PEN International and English PEN set up meetings in the British Parliament where celebrated writers spoke. English PEN mounted candlelight vigils outside the Nigerian High Commission which writers including Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri, Harold Pinter, Margaret Drabble and International PEN President Ronald Harwood attended. A theater event in London featured Nigerian actors acting out extracts from Ken’s plays and also reading poems from other writers in prison. Taslima Nasreen spoke as well. Ken’s writing was made available to the press which covered the story widely.

Poem from Malawian poet Jack Mapanje to Ken Saro-Wiwa published on page 2 of PEN Campaign document above

The activity in London mirrored activity at PEN’s more than 100 centers around the globe, from New Zealand to Norway, from Malawi to Mexico. From every continent signed petitions were faxed to the Nigerian government of General Sani Abacha and to the writers’ own governments, to members of Commonwealth nations, to the European Union, the United Nations and to the press calling for clemency for Ken Saro-Wiwa. Through the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) of which PEN International was a founding member, the word spread to freedom of expression organizations worldwide. Other human rights organizations including Amnesty and Greenpeace also protested. No one wanted to believe in the face of such an international outcry that the generals in Nigeria, particularly Nigeria’s President Sani Abacha, would kill Ken Saro-Wiwa.

Ken managed to get word out that he was tortured and held in leg irons for long periods of time. He wrote to Mandy, “A year is gone since I was rudely roused from my bed and clamped into detention. Sixty-five days in chains, many weeks of starvation, months of mental torture and, recently, the rides in steaming, airless Black Maria to appear before a Kangaroo court, dubbed a Special Military Tribunal where the proceedings leave no doubt at all that the judgement has been written in advance. And a sentence of death against which there is no appeal is a certainty.”

I moved from London to Washington, DC in late August 1995. When the death sentence was handed down at the end of October, PEN International launched a petition signed by hundreds of writers from around the globe seeking Saro-Wiwa’s and others’ release. For days I tried to get an appointment with the Nigerian Ambassador in Washington. Finally one morning I received a call that I had been given an appointment; however, I was in New York City that morning. Quickly I got a flight back to Washington. En route I called the former PEN WiPC director Siobhan Dowd, who was then heading the Freedom to Write program at American PEN. I asked her to arrange for a second writer to meet me at the Nigerian Embassy. The person didn’t have to say anything, but I wanted a larger delegation.

When I arrived, I was informed the Ambassador had suddenly been called to the U.N. in New York so I met with the number two and three ministers. As I began setting out PEN’s case on behalf of Saro-Wiwa, another woman slipped into the room and sat without speaking but lending ballast to the meeting. Afterwards she and I had coffee, and I briefed her on the case. For the next 25 years Susan Shreve, one of the founders of the PEN Faulkner Foundation, and I have been friends, a friendship that grew out of this tragic event. A few days later I was standing outside the Nigerian Embassy in a vigil, along with representatives from Amnesty and other organizations, when word was sent out to us that Ken Saro-Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt.

Article from The Washington Post November 11, 1995

The effect of his execution raced through the PEN network and through the human rights and political communities worldwide. The grief was communal. Those who worked on Ken’s case can relate to this day where they were when they heard the news of the execution. The shock was also political. Boycotts were launched against Nigeria. Archbishop Desmond Tutu appeared at a benefit in London for Ken Saro-Wiwa and reported outrage in South Africa over the executions of Saro-Wiwa and the others. He said South African President Nelson Mandela was heading up a campaign to urge the world, especially the US and Western governments to take action. Nigeria was suspended from the British Commonwealth for three years.

Ken’s brother quickly left Nigeria and went to London for a period, sheltering temporarily with British novelist Doris Lessing then relocated in Canada for a time. Ken Saro-Wiwa’s son, Ken Saro-Wiwa Jr., a journalist, also settled in Canada, then in London, then returned and worked for a period in the Nigerian government of Goodluck Jonathan as a special assistant on civil society and international media. He died suddenly in London at age 47 in 2016.

Letter on left from Ken Saro-Wiwa to PEN researcher Mandy Garner. Letter on right from Ken Saro-Wiwa, Jr. to WiPC Chair Joanne Leedom-Ackerman.

The killing of Ken Saro-Wiwa was the beginning of the end for General Sani Abacha, who maneuvered to be the sole presidential candidate in Nigeria’s next election, but died in June, 1998 when he suddenly got ill early one morning and died within two hours, at age 54, the same age as Ken Saro-Wiwa when he was hanged. There were persistent rumors that Abacha had been poisoned, but there was no autopsy and these rumors were never proven.

According to news reports in Lagos, it took five attempts to hang Ken Saro-Wiwa. He was buried by security forces, denying his family the right to bury him. His last words were reported to be: “Lord, take my soul, but the struggle continues.”

Releases of writers PEN worked for that year included Cuban poet Yndamiro Restano freed after serving three years of a ten-year sentence, Cuban journalist Pablo Reyes Martinez freed after three years on an eight-year sentence, Turkish writer Fikret Baskaya freed early and also Unsal Ozturk, freed eight years early, Chinese writer Yang Zhou freed after serving one year of a three-year sentence and Wang Juntao freed after serving five years of a 13-year sentence, Burmese Zargana freed a year early and many others.

“I wish to thank International PEN and the WiPC for all their endeavors on my behalf during the period of my detention. There is no doubt in my mind at all that the powerful insistence and impartial voice of PEN did a lot to win me my freedom from the tyrannical arms of the military dictatorship in Nigeria…”—Ken Saro-Wiwa in fall, 1993 after his earlier detention.

From Ken Saro-Wiwa’s poem “A Walk in the Prison Yard”

Next Installment: PEN Journey 16: The Universal, the Relative and the Changing PEN