Posts Tagged ‘PEN International’

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

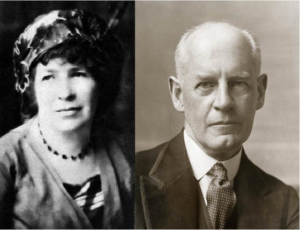

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

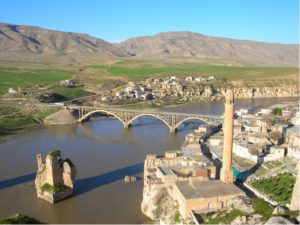

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International

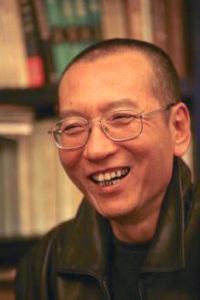

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo died this past July in prison, where he was serving an 11-year sentence for his role in drafting Charter ’08 calling for democratic reform in China. Below is my essay in The Memorial Collection for Dr. Liu Xiaobo, just published by the Institute for China’s Democratic Transition and Democratic China.

I never met Liu Xiaobo, but his words and life touch and inspire me. His ideas live beyond his physical body though I am among the many who wish he survived to help develop and lead democratic reform in China, a nation and people he was devoted to.

Liu’s Final Statement: I Have No Enemies delivered December 23, 2009 to the judge sentencing him stands beside important texts which inspire and help frame society as Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail did in my country. King addressed fellow clergymen and also his prosecutors, judges and the citizens of America in its struggle to realize a more perfect democracy.

I hesitate to project too much onto Liu Xiaobo, this man I never met, but as a writer and an activist through PEN on behalf of writers whose words set the powers of state against them, I can offer my own context and measurement.

Liu said June, 1989 was a turning point in his life as he returned to China to join the protests of the democracy movement. In June, 1989 I was President of PEN Center USA West. It was a tumultuous year in which the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was issued in February, and PEN, including our center, mobilized worldwide in protest.

In May, 1989 I was a delegate to the PEN Congress in Maastricht, Netherlands where PEN Center USA West presented to the Assembly of Delegates a resolution on behalf of imprisoned writers in China, including Wei Jingsheng, and called on the Chinese government to release them. The Chinese delegation, which represented the government’s perspective more than PEN’s, argued against the resolution. Poet Bei Dao, who was a guest of the Congress, stood and defended our resolution with Taipei PEN translating.

When the events of Tiananmen Square erupted a few weeks later, my first concern was whether Bei Dao was safe. It turns out he had not yet returned to China and never did. PEN Center USA West, along with PEN Centers around the world, began going through the names of Chinese writers taken into custody so we might intervene. I remember well reading through these names written in Chinese sent from PEN’s London headquarters and trying to sort them and get them translated. Liu Xiaobo, I am certain must have been among them, though I didn’t know him at the time.

In his Final Statement to the Court twenty years later, Liu told the consequence for him of being found guilty of “the crime of spreading and inciting counterrevolution” at the Tiananmen protest: “I found myself separate from my beloved lectern and no longer able to publish my writing or give public talks inside China. Merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his right to teach, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual could no longer speak openly. Whether we view this as my own fate or as the fate of a China after thirty years of ‘reform and opening,’ it is truly a sad fate.”

I finally did meet Wei Jingsheng after years of working on his case. He was released and came to the United States where we shared a meal together at the Old Ebbit Grill in Washington. I was hopeful I might someday also get to meet Liu Xiaobo, or if not meet him physically, at least get to hear more from him through his poetry and prose.

His words are now our only meeting place. His writing is robust and full of truth about the human spirit, individually and collectively as citizens form the body politic. I expect that both his poetry and the famed Charter 08, for which he was one of the primary drafters and which more than 2000 Chinese citizens endorsed, will resonate and grow in consequence.

Charter 08 set out a path to a more democratic China which I hope one day will be realized.

“The political reality, which is plain for anyone to see, is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government,” noted Charter 08. “The ruling elite continues to cling to its authoritarian power and fights off any move toward political change….

“Accordingly, and in a spirit of this duty as responsible and constructive citizens, we offer the following recommendations on national governance, citizens’ rights, and social development: a New Constitution…Separation of Powers…Legislative Democracy…an Independent Judiciary…Public Control of Public Servants…Guarantee of Human Rights…Election of Public Officials…Rural—Urban Equality…Freedom to Form Groups…Freedom to Assemble…Freedom of Expression…Freedom of Religion…Civic Education…Protection of Private Property…Financial and Tax Reform…Social Security…Protection of the Environment…a Federated Republic…Truth in Reconciliation.”

Charter 08 addresses the body politic. Liu Xiaobo’s Final Statement: I Have No Hatred addresses the individual, and for me resonates most profoundly. Its call doesn’t depend on others but on oneself for execution. He warned against hatred.

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows). It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

At a recent conference a participant asked if Liu Xiaobo might have changed this statement if he understood how his life would end. A friend who knew him assured that he would not for he was committed to the idea. Liu Xiaobo’s commitment to No Enemies, No Hatred does not accede to the authoritarianism he opposed, but instead resists the negative. He aligns with benevolence and love as the power that nourishes the human spirit and ultimately allows it to flourish. Liu’s words and his ideas lived offer us all a beacon and a guide.

Reclaiming Truth In Times Of Propaganda

PEN International’s 83rd Congress in Lviv, Ukraine took on truth and words, history and memory, women’s access and equality, cyber trolling, fake news and threats to freedom of expression worldwide, including public panels focused on the three super powers: “America’s Reckoning—Threats to the First Amendment in Trump’s America,” “China’s Shame—How a Poet Exposed the Soul of the Party,” and “Putin’s Power Play—The Decline of Freedom of Expression in Russia.”

At its annual gathering PEN hosted more than 200 writers, editors, staff and visitors from 69 PEN centers around the world in the historic city of Lviv, the Cultural Capital of Ukraine and a UNESCO World City of Literature. Straddling the center of Europe, on the fault lines between East and West, Lviv changed its name and governing domain eight times between 1914 and 1944, passing from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to Russia, back to Austria, Ukraine, Poland, Soviet Union, Germany then back to the Soviet Union and now finally in the Ukraine.

The path of European history cuts through the city and can be seen in architecture, culture and conversation. Though writers celebrated literature in the western Lviv, fighting was still underway in eastern Ukraine and the Crimea. PEN’s Russian center didn’t attend the Congress at the same time a new PEN St. Petersburg center was elected. Other new centers joining PEN’s network included Cuba, the Gambia and South India.

In times of war, the first casualty is truth, noted PEN’s report “Freedom of Expression in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: External Aggressions, Internal Challenges.” The report and the Congress addressed the aggressive role of propaganda in conflict. In Ukraine, in Russia and worldwide there has been a proliferation of false narratives.

PEN’s report on Ukraine noted: “Despite significant improvements, democracy in Ukraine remains ‘a work in progress’ and, among other things, severe challenges to the enjoyment of the right to free expression remain. These include the use of the media to foster political interests and agendas, delays in reforming state-owned media; and intimidation and attacks on journalists followed by impunity for the perpetrators. On the other hand, public criticism is growing, albeit slowly, including demands for more transparent and unbiased journalism.”

In Russia authorities are taking increasingly extreme legal and policy measures against freedom of expression, according to a PEN/Free Word Association report “Russia’s Strident Stifling of Free Speech.”

No writers are in prison in Ukraine, but in the Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014, filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, an opponent of annexation, was arrested and is now serving a 20-year sentence inside a Russian prison on terrorism charges he denies. At PEN’s Assembly, delegates remembered Pavel Sheremet with an Empty Chair. A Belarusian-born Russian journalist and free speech advocate, Sheremet wrote for an independent news website and hosted a radio show where he reported and commented on political developments in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. He died in a car bomb explosion in Kiev July, 2016. Shortly before he was assassinated, he’d written about corruption among law enforcement in Belarus, Ukraine and propagandists in Russia. His murder remains unsolved.

Resolutions at the Congress also addressed writers imprisoned in Turkey, China, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, and Eritrea and killings in Mexico, Russia, Venezuela, Bangladesh and India. Concerns about increasing censorship in Hungary, Poland, India, Turkey, and Spain were acted on as was the restriction of linguistic rights for Kurdish writers in Turkey, Hungarians in Ukraine and Uyghurs in China.

Expressing concern about the abuse of Interpol’s Red Notice system by some member states “in order to repress freedom of expression or to persecute members of political opposition beyond their borders”, PEN called on the Council of Europe “to refrain from carrying out arrests…when they have serious concerns that the notice in question could be abusive.”

PEN expanded Article 3 of its Charter for the first time since the document’s inception over 90 years ago. The Assembly voted new language which would include a wider mandate, reaching beyond just opposing hatreds of race, class and nations to include by extension gender, religion and other categories of identity. Article 3 of PEN’s Charter, which can be linked to here, now reads: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

PEN also passed a Women’s Manifesto noting “the use of culture, religion and tradition as the defense for keeping women silent as well as the way in which violence against women is a form of censorship needs to be both acknowledged and addressed.”

At the Opening Ceremony author of East West Street Philippe Sands, whose grandfather was born in Lviv, narrated the origins of international human rights law and the concepts “crimes against humanity” and “genocide.” These legal frameworks were developed by two lawyers who passed through the very university where the delegates sat. The legal teams prosecuting at the Nuremberg trials after World War II used these frameworks to secure convictions, including the conviction of Hans Frank, Hitler’s lawyer who governed the area around Lviv and sent over 100,000 Jews to concentration camps and death.

“The Foundations of human rights law came from here,” Sands said. “Every individual has rights under international law.” The lawyers Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin studied at the university at different times and never met. One escaped to Austria then England, the other to America. Lauterpacht protected the rights of the individual with the concept he developed of “crimes against humanity” and Lemkin protected the group with the legal construct for “genocide.” Both men were on the legal teams that successfully secured convictions at Nuremberg.

“No organization in the world knows better than PEN the need to protect individuals and to protect others,” Sands concluded.

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President

Andrei Kurkov from Ukranian PEN and Carles Torner, Executive Director PEN International

At the closing ceremony author David Patrikarakos focused on the current situation as the 21st century unfolds and addressed “Fact, Fiction and Politics in a Post Truth Age.” He told the story of Vitali, who became a troll for the Russian state working at a Troll farm. “When Vitali went to the Troll farm, he had enlisted in the Russian Army; he just didn’t wear a uniform. He and others became their own army with a virtual information war, and it is effective,” said Patrikarakos.

As an unemployed journalist, Vitali developed propaganda, rewriting reports, doctoring news accounts to enhance Russia’s position then distributed these on social media, along with fake news, fake pictures and memes to a wide audience, all relating to Russia’s assault on the Crimea. According to Patrikarakos (Nuclear Iran: The Birth of an Atomic State), who has also written for the New York Times, Financial Times, Guardian, and Wall Street Journal, the Russian state spent $250 million to sow discord in its battle for Crimea.

In the Troll farm where Vitali and other journalists worked, the first floor focused on distorting news reports and circulating them. On the second floor people worked through social media, posting memes and making up ads; on the third floor bloggers wrote about how life was better in Russian and bad for Russians in the Ukraine and on the fourth floor, people posted comments on other sites.

According to Patrikarakos and his sources, there was a bag of sim cards to request new accounts, and people were encouraged to make the accounts in the names of females because women were more likely to be believed. “The first goal was to shore up and get true believers, to give a narrative and sow as much confusion on reality as possible,” Patrikarakos said.

After three months Vitali told his boss he wanted to quit. He wrote an expose of the Troll farm. When it came out, he received threats such as “Don’t you know you can get punched in the face.”

“As I went through towns of Eastern Ukraine, content had seeped into walls,” said Patrikarakos. “In Eastern Ukraine, Putin’s nervous system is on display. There is belief in fake news—that Ukrainians want to kill Russian speakers. Social media is supposed to connect us but it has also shattered unity and divided people; it sets people at loggerheads. The news that young people get depends on who they follow. We all follow who we like, and so prejudice is reaffirmed. Facts are less important than narratives. The new word in 2016 from the Oxford dictionary was ‘post-truth’ which is finding linguistic footing. The goal of many is not to trust truth but to subvert truth,” he concluded.

What can we do to counter this trend? Patrikarakos advised:

- Go out of your way to see people who don’t think like you.

- Go directly to the source of information and go to the news.

- Read those you don’t agree with.

- Read books. (Patrikarakos’ new book is More Than 140 Characters)

- Mistrust the mob.

- Beware of Click bait.

- Click off.

In Turkey, a show of solidarity with writers behind bars

Commentary: For the first time in two decades, Turkey is again the largest jailor of writers and publishers in the world. A PEN International delegation tried to visit a prison where most are incarcerated.

By Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, published in The Christian Science Monitor, February 3, 2017

Snow was falling outside Silivri prison as we drove up the road bordered by high wire fences. A senior delegation of PEN International from Europe, North America, and the Middle East had come to Turkey in solidarity with the more than 150 Turkish writers and publishers now in prison. The majority of these were incarcerated behind the walls of Silivri.

For the first time in two decades, Turkey is again the largest jailor of writers and publishers in the world. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who came to power in 2002, civil institutions have been increasingly circumscribed. In the past six months more than 170 news outlets have been closed by the government. A third of Turkey’s judiciary – judges and prosecutors – have lost their jobs and/or been put in prison. University presidents have been fired; thousands of academics have been forced to resign, and more than 140,000 civil servants and military personnel have been purged; a third of these are now in detention. Ever since a coup attempt last July, Turkey has existed in a declared “state of emergency.” Those who oppose the government have been labeled and charged as “terrorists” or “supporters of terrorist organizations.” The crackdown that was already under way before the coup attempt has escalated.

At Silivri, our delegation was restricted to a remote parking lot. The prison officials had been notified the delegation would be arriving, but the gendarmes who encountered us appeared unprepared. Eventually they returned us to our minivans and encircled these and blocked us with police vehicles as they collected our passports. A young gendarme with an assault rifle boarded our bus, impeding our exit for almost an hour, though he appeared unsure of what he was supposed to do with us except keep us from taking pictures. Finally the delegation, which included three current and former International PEN presidents, including the current chair of the Nobel Prize for Literature, were escorted away from the prison. There was no interchange with prison officials or meetings with the writers behind bars. The cars were stopped again outside the grounds by the police, and our passports were once more collected. After approximately two hours, our two white minivans turned back to Istanbul.

Earlier, in the Turkish capital of Ankara, a smaller delegation of PEN met with the minister of Culture and other government officials to protest and express deep concern over the restriction of free expression and the imprisonment of writers and publishers in Turkey. PEN questioned the legitimacy of the constitutional referendum President Erdoğan is putting on the ballot this spring. The referendum will expand the powers of the presidency, giving Erdoğan the ability to suspend parliament as well as rights and due process, “extorting individual rights and freedom” by statutory decree. It could allow him to stay in office until 2029. While PEN, which promotes literature and defends freedom of expression worldwide, does not take political positions, it challenged the legitimacy of a referendum held during a state of emergency, when opposition voices are silenced.

After our delegation returned from the prison to Istanbul, we met with recently released writer Asil Erdoğan (no relation to the president), linguist Necmiye Alpay, and others, including the spouses of writers still in prison or killed. “It is not our husbands in prison, but journalism,” said the wife of one. “Journalism is a prerequisite for a country to have a free press. If we don’t have a free press, we can’t be considered anything. Don’t use the word “journalist” and “terrorist” together. It is very sad to see.”

Several of the writers noted that often no indictment is made when individuals are detained. They are held without charge because the prosecutors can’t find anything to charge them with. See #Journalismisnotacrime.

A new effort

One newspaper, Özgür Gündem, which had a large Kurdish readership, was shut down in August after 25 years. But a new newspaper, Demokrasi, has grown up out of its staff and readership.

At the top of a steep four-floor walkup, writers, photographers, and editors work to put out the daily paper with a readership of 30,000. The design and layout team work elsewhere as do some of the writers and other organs of the paper, in the belief that the more decentralized the operation, the better chance it has to survive.

“The government wants to eliminate the Kurdish movement – the language, the news we report. They want a single state, single religion, single language,” said one of the editors. “Kurds are not only the target; our newspapers are the target. We are OK with a single flag, but we don’t want religion and language imposed.”

The Turkish government has fought with Kurdish separatists for decades. A cease-fire from 2013-15 held out prospects for a more lasting peace and for the allowance of Kurdish language and culture to be recognized as part of Turkish identity. The rapprochement broke down, however, after the predominantly Kurdish HDP party won enough votes in June 2015 to secure seats in parliament and deny Erdoğan and his AKP party its parliamentary majority and the supermajority he was seeking for his constitutional changes. Hostilities with the Kurds were renewed shortly afterward. A new election was held in November 2015, and the AKP party won its majority.

The gray-haired editor of Demokrasi spoke calmly behind an empty desk in a sparse room with pale yellow walls. He acknowledged that the state police could come at any moment to take him away, but there would be others to take his place. “We received support from 100 journalists who volunteered to be editor-in-chief at Özgür Gündem. Thirty-seven of those are now on trial. But it is not a problem for us to repeat.”

As we left the Demokrasi office, the editor with his photographer stood at the top of the stairs in the shadow of a half-opened door, the light behind them. “Thank you for solidarity!” he said.

When we emerged, the sun was setting. The winding backstreet was filled with people as the lights of shops and apartments readying for dinner flickered on, and the snow continued to fall.

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman visited Turkey as part of a delegation from PEN International, where she is a vice president. Ms. Leedom-Ackerman is also a former reporter for the Monitor.

(Click here to read the article at The Christian Science Monitor.)

Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

The last time I saw Şanar Yurdatapan we had coffee in the press building in Istanbul after Human Rights Watch released its 2016 World Report “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society”. I’ve known Şanar for almost 20 years, ever since I headed PEN International’s delegation for his first Initiative for Free Expression in Istanbul in 1997.

A noted and popular musician and song writer, Şanar has dedicated the last decades to defending and trying to open up space in Turkey for free expression. He’s done so by monitoring, reporting and organizing on behalf of writers and artists under threat. At our coffee a year ago he told me he was retiring, or at least going back to song writing and handing over the mantle of leadership to the younger generation.

However, in the past year freedom of expression has been under siege in Turkey with 150-170 writers and journalists now in prison and hundreds of news organizations closed down. This past week Şanar was called before prosecutors for his advocacy on behalf of the closed newspaper Özgür Gündem, (Turkish for “Free Agenda”), the chief newspaper read by Kurds.

“It is both the duty and the right of a journalist to report; his is freedom of information at the same time and right to freedom and right of all of us,” Şanar is reported to have told the court.

At the end of the hearing the prosecutor demanded that Şanar be imprisoned for over ten years for “propaganda for the organization” under the Anti-Terror Law. The hearing is January 13, 2017. Şanar is now 75.

Since the failed coup in July the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has increased the detainment and arrest of writers, journalists and academics for their peaceful opposition to his policies. These have included noted novelist Asli Erdoğan and leading linguist Necmiye Alpay, who spent her 70th birthday in detention. Brothers Ahmet Altan, a novelist, and Mehmet Altan, an academic, are held in maximum security Silivri prison facing terror charges, unable to receive books, letters or any communication from outside or to visit the prison library.

As the year 2016 ends with an increase of terror attacks around the world, with a new administration about to take power in the U.S., with existing administrations struggling to hold onto power in Europe, with a collapsing Syria and a continual tide of refugees around the world, with an odd dance between super powers and aspiring super powers, the single citizen voice can get overlooked. But history has shown that when the individual voice, especially those of writers who dissent, gets stifled, the arc of history is bending towards conflict and away from peace which leaders and citizens say they want.

In the new year PEN International hopes to go to Turkey to add support firsthand for Turkish writers and for the important role they play right now in keeping that arc from bending too far backwards. We will watch and argue for the fate of Şanar and others and hope that he will be writing songs in the years ahead, and not from prison.

Building Literary Bridges: Past and Present

Gathered in the ancient city of Ourense, Spain in the heart of Galicia, writers from around the world celebrated history, debated the present and committed to the future of literature and freedom of expression at PEN International’s 82nd Congress organized around the theme “Building Literary Bridges.”

Two hundred poets, novelists, dramatists and nonfiction writers from approximately 75 centers of PEN agreed to embark on a three-year global campaign to increase opportunities for displaced writers worldwide. Responding to the unprecedented flow of refugees, migrants, and displaced, all of which include writers and those whose stories need to be told, the 95-year old literary organization will undertake an initiative to put storytelling and literature at the center of an effort to heal and expand opportunities. Through its 145 centers, PEN will develop programs that will include residencies, workshops, mentoring, education and publications. The full scope of the campaign will be announced December 10, Human Rights Day.

Founded in 1921 out of the chaos and refugee flows after World War I, PEN anticipated and protested the suppression of freedom of expression in Nazi Germany prior to World War II and defended writers throughout Europe during the war, offering haven and setting up PEN centers in exile.

“PEN responds to the crises of our times,” said PEN International President Jennifer Clement. “We are writers. We believe in imagination.”

The 82nd Congress began with heartening and dispiriting news. Iranian-Canadian writer Homa Hoodfar was released from Iran’s Evin prison at the same time news arrived that Jordanian columnist Nahed Hattar had been gunned down outside court by a fundamentalist who claimed Nahed deserved to die for his ideas.

This pattern of good and terrible news also emerged in the past year with early releases of imprisoned writers in Tibet, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Vietnam, Qatar and Colombia at the same time the situation deteriorated with more arrests and killings in Bangladesh, China, Turkey, Ukraine and other countries.

The tradition of an Empty Chair at the PEN Congress sessions highlighted the cases of imprisoned Egyptian novelist Ahmed Naji, Kurdish journalist Asli Erdogan, Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour, and Gui Minhai, a bookseller in Hong Kong, who was kidnapped by the Chinese government while he was in Thailand.

Gui’s daughter, a Swedish citizen as is he, sent a letter to the Congress: “In the end, this is not about my father as an individual…. This is about China actively extending its control far beyond its own borders. This is about China kidnapping and illegally detaining more and more people because of their political beliefs. It’s about European citizens no longer being able to know that their human rights will be protected.”

Discussing “Literature as a Tool for Empowerment,” delegates shared ongoing projects, including working with young writers in schools and in prisons. Lebanon PEN Center’s delegate noted, “I discovered the tremendous effect from creative writing to express trauma and help people tell their stories. We have 1.3 million Syrians in Lebanon. We have a big responsibility. We see the empowerment of civil society through literature.”

In Mali and Sierra Leone, the PEN centers work with students and young people in post-conflict situations. The Mali delegate spoke about workshops with Tuareg warriors who had fought on the battlefield in the Sahara. When they returned home, they had lost their dignity and positions and were migrants so they went to join the ranks of Gadhafi. After Gadhafi was toppled, there was a big problem, he said, and conflict. The Mali PEN Center helped organize writing workshops which led to publishing books. Hundreds attended these workshops and were able to tell their stories and see them published.

PEN’s earliest work to protect writers began when poet Federico Garcia Lorca was arrested at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. PEN President H.G. Wells sent a telegram protesting, but it arrived too late and Lorca was executed. At the 82nd PEN Congress, Lorca’s niece Laura opened the Assembly with Lorca’s poem Sonnet:

I know that my profile will be serene

In the north of an unreflecting sky.

Mercury of vigil, chaste mirror

to break the pulse of my style.

For if ivy and the cool of linen

are the norm of the body I leave behind,

my profile in the sand will be the old

unblushing silence of a crocodile.

And though my tongue of frozen doves

will never taste of flame,

only of empty broom,

I’ll be a free sign of oppressed norms

on the neck of the stiff branch

and in an ache of dahlias without end.

–Federico Garcia Lorca

Call for Help inside Iran’s Evin Prison

Shared below is a letter that managed to get out of Iran’s infamous Evin Prison from journalist and human rights activist Narges Mohammadi. She is detained on charges of “gathering and colluding to commit crimes against national security” and “spreading propaganda against the system.” According to reports she has also been charged with “insulting officers while being transferred to a hospital” because of her health. Narges Mohammadi is former vice president and spokesperson of the Defenders of Human Rights (DHRC) which represents prisoners of conscience. She is also involved in a campaign against the death penalty in Iran.

On May 17 the verdict in her case was handed down. Narges Mohammadi was sentenced to five years in prison for “meeting and conspiring against the Islamic Republic,” one year for “spreading propaganda against the system” and ten years for her work advocating against the death penalty. Under Iranian penal code, a person with several jail terms must serve the most severe so she must serve ten years, although sentenced to 16 years total.

Dear members of International PEN,

I’ m writing this letter to you from the Evin Prison. I am in a section with 25 other female political prisoners, with different intellectual and political point of view. Until now 23 of us, have been sentenced to a total of 177 years in prison (2 others have not been sentenced yet). We are all charged due to our political and religious tendency and none of us are terrorists.

The reason to write these lines is, to tell you that the pain and suffering in the Evin Prison is beyond tolerance. Opposite other prisons in Iran, there is no access to telephone in Evin Prison. Except for a weekly visit, we have no contact to the outside. All visits takes place behind double glass and only connected through a phone. We are allowed to have a visit from our family members only once a month.

But it is the solitary confinement, which is beyond any kind of acceptable imprisonment. We – 25 women – have detained in total more than 12 years in solitary confinement. Political prisoners who are considered dangerous terrorists are held in solitary confinement indefinitely. Retention in solitary confinement can vary from a day up to several years.

However, according to regulations of the Islamic Republic of Iran, holding prisoners in solitary confinement is illegal. Unfortunately until now, the solitary confinement, as a psychological torture, has had many victims in Iran.

During 14 years long activity of the Center for Human Rights Defenders, the Center have published and held many protests against the use of this kind of punishment. But unfortunately the solitary confinement is still used against many of Iran’s political prisoners. The solitary confinement is used to get forced and false confessions out of the defendants. These false and faked confessions are used against the defendants during the trials. Many of the detainees in the solitary confinement are suffering from mental and physical health problems and the injuries will remain with them for the rest of their life. As a matter of a fact, the solitary confinement is nothing but a closed and dark room. A dimly confined space, deprived of all sounds and all light that can give the inmates a sense of humanity. Personally, I have been in solitary confinement three times since 2001. Once during my interrogation in 2010, I suffered a panic neurotic attacks, which I had never experienced before.

As a defender of human Right, who has experienced and have had dialogues with many people detained in solitary confinement, I emphasize that this kind of punishment is inhuman and can be considered psychological torture.

As a humble member of this prestigious organization, I urge all of you, as writers and defenders of the principles of free thought and freedom of speech and expression, to combat the use of solitary confinement as torture, with your pen, speech and all other means. Maybe one day we will be able to close the doors behind us to solitary confinement and no one will be sentenced to prison for criticizing and demanding reforms. I hope that day will come soon.

Greetings and Regards

Narges Mohammadi

Prison Evin, May 2016

For more information on Narges Mohammadi and suggested action, you can link to PEN International.

Spring and Release

I saw the first daffodils today…and forsythia…and the buds on cherry blossom trees. Spring with its regalia is starting to blossom, at least here in Washington, DC.

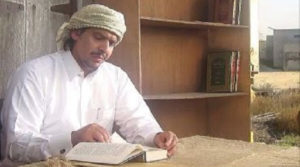

In the freedom of expression community renewal is heralded this week by the release of writers from prison in a number of countries, including Qatar, China and Azerbaijan. While the writers were unjustly imprisoned in the first place and many hundreds still languish in jails because they have offended governing powers, the releases of Qatar poet Mohammed al-Ajami after almost five years in prison and Chinese writers Rao Wenwei and Wang Xiaolu and half a dozen writers in Azerbaijan are cause for quiet celebration.

Qatar: In the fall of 2013 another PEN colleague and I stood outside the sprawling prison in the desert around Doha where Mohammed Ibn al-Dheeb al-Ajami was held in solitary confinement. After meetings with Justice Ministry officials, we’d understood we would be allowed into the prison for a visit. However, after five hours waiting in the desert wind, we were denied access. Al-Ajami’s family, who were visiting inside, told us later that Al-Ajami knew we were there and took some heart in that. Al-Ajami was imprisoned for “insulting the Emir” in two poems which he read at a private apartment in Cairo but which were surreptitiously recorded and posted by a student on YouTube. One of the poems “Tunisian Jasmine” expressed support for the uprising in Tunisia that launched the Arab Spring and challenged rulers throughout the region. Al-Ajami, who is the father of four, was originally sentenced to life in prison, reduced to 15 years.

PEN centers around the world, including American, Austrian, English and German PEN worked on his behalf as did Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and other organizations championing freedom of expression. Many voices protested, many hands tried to push open the prison door. Just last week at a Washington dinner I noted Al-Ajami’s imprisonment to an individual headed to Qatar for high level meetings. Those who deal with Qatar are always surprised that this Emirate which boasts education and partnerships with Western universities would imprison a poet for his poems. It is not a comfortable outcome that it is a pardon and not an apology by the Emir which brought about Al-Ajami’s release, but it is still cause to be glad.

China: There are more than 40 writers in prison in China, including Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo. Recently two—Rao Wenwei and Wang Xiaolu—were released early. Rao Wenwei is a writer charged with “inciting subversion of the state power” for articles published on the internet. His 12-year sentence was cut short by four years with his release. Wang Xiaolu was arrested for a story on the stock market crash on suspicion of “fabricating and disseminating false information on the trading of securities and futures.” Through the efforts of PEN centers, particularly the Independent Chinese PEN Center, the cases and situation of writers in prison in China stay at the forefront of protests.

Azerbaijan: Half a dozen writers are being released in Azerbaijan this month. The Baku Court of Appeals is expected to release journalist Rauf Mirkadirov today, according to Sports for Rights coalition which includes PEN, commuting his six-year prison sentence to a five-year suspended sentence. President Aliyev has signed a pardon decree that includes 14 political prisoners, including the writers Parviz Hashimli (journalist), Abdul Abilov (blogger), Hilal Mammadov (journalist), Omar Mamedov (blogger) and Tofiq Yaqublu (journalist). The European Court of Human Rights also issued a judgment in Rasul Jafarov’s case finding violations of Rasul’s rights to liberty and security. Rasul is expected to be released shortly. Dozens of political prisoners, however, remain in Azerbaijani jails, including journalists Khadija Ismayilova and Seymur Hezi.

(*For background on any of these cases or the many remaining political prisoners in Azerbaijan, here’s the full list with case details: http://www.helpsetthemfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/The-list-of-Political-Prisoners-in-Azerbaijan_December-2015.pdf)

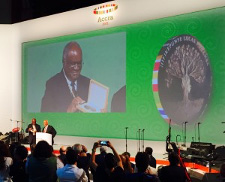

Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

I returned last week from two conferences and a debate back to back in Africa. The Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which has developed an index on good governance and transparency in Africa, gave its annual prize to a former African leader, followed by a day-long discussion on “African Urban Dynamics.”

The Africa Report Debates inaugurated its series with the question: “Democracy vs. Development.”

And the International Crisis Group, an organization dedicated to analyzing and offering policy recommendations for current and potential conflicts worldwide, (and on whose board I serve) gathered its Africa program for an internal analysis.

From the gatherings of eminent African leaders, policy makers, scholars and commentators I took away the following contradictions across the continent:

–There is an expanding and active civil society at the same time there are spreading and virulent extremists and criminal networks.

–There are growing numbers of working democracies at the same time entrenched leaders are trying to change constitutions to hold onto power in single-party states.

–There is developing urbanization offering services and employment for citizens while slums and marginalized communities expand.

The debate “Democracy vs. Development” concluded overwhelmingly that the two must go hand in hand.

“Fast and equitable development and diversity come through democracy,” according to Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Ethiopia. But he added, “Democracy is a process. It matures over time and grows from the inside. It can’t be prescribed. It needs institutions and education. We don’t need paternalistic intervention.”

Ethiopia was pointed to throughout as making significant economic progress. But in a break between panels, I asked Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus about the restrictions on freedom of expression in Ethiopia and the number of writers and journalists now in prison there. His answer: “They broke the law.” Their imprisonments have been challenged by major freedom of expression organizations like PEN International, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty, Committee to Protect Journalists, as well as by African PEN centers, I pointed out; this is not a positive sign for healthy government. He and I did not resolve the question between us.

Good news and reasons for hope on the continent include the peaceful elections and transfer of power this year in Nigeria, which has a strong and vocal civil society even as it struggles with the radical extremism of Boko Haram in the North and with criminal trafficking. Also positive is the immanent transfer of power through elections in Burkina Faso, where citizens rose up peacefully last year and opposed the extended 27-year rule of its leader, demonstrating a strengthening civil society. Ghana, where the conferences convened, held peaceful Parliamentary elections while we were there.

“We need heroes,” said Mo Ibrahim, who initiated the conference and the award which was given to the former President of Namibia. Hifikepunye Pohamba won the $5 million prize for “forging national cohesion and reconciliation at a key stage of Namibia’s consolidation of democracy and social and economic development.”

“We must reject the manipulation of the Constitutions,” said former President Pohamba in his acceptance speech. “No individual or group of people should be allowed to abuse power from democratically elected leaders with impunity.”

Electoral transitions in East, West and Southern Africa could unhinge or advance their regions, including in Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Cameroon, Uganda and Zimbabwe. In many of these countries, the current presidents are hoping to hold onto power past constitutional limits which they are trying to alter or past public tolerance. Outcomes of these elections will be important indicators to watch.

Informal conversation outside the symposiums:

“Who can chat with Kabila?” (President of DRC). “I understand he’s scared. His father was killed here.”

“Who can offer him immunity?”

“Can he have a soft exit?”

“Will he exit?”

“I don’t think so.”

Behind all the statistics and the headlines, the story after all is always about people.

Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance

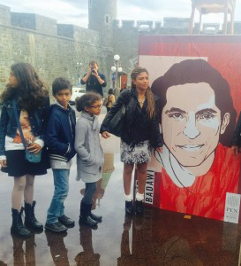

Of all the lively discussions, the literary evenings, multiple resolutions generated at PEN International’s 81st Congress last week in Quebec City, the image that stays in my mind is of the petite wife and children of Saudi blogger and editor Raif Badawi standing in a puddle on the plaza by his picture in the early morning, along with delegates from PEN centers around the world.

His wife and children now live in Quebec, which has also offered Raif Badawi a home, but he remains in a Saudi prison with a ten-year sentence and 950 more lashes of punishment, then a decade long ban on travel, all for setting up a digital forum to encourage social and political debate within Saudi Arabia. He has been found guilty of “insulting Islam” and “founding a liberal website.”

The PEN Congress, which hosted writers from 84 centers in 73 countries, featured three writers with “empty chairs,” including Raif Badawi, Eritrean poet, critic and editor Amanuel Asrat and murdered Honduran journalist Juan Carlos Argenal Medina. PEN called for the release of Badawi and Asrat and justice for Medina. It also targeted the cases of writers imprisoned, threatened, killed or at risk in Bangladesh, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Honduras, India, Iran, Mexico, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Tibet, Turkey and Vietnam.

Badawi’s message via his wife to PEN members after receiving an earlier PEN Canada One Humanity Award was: “We want life for those who wish death to us, and we want rationality for those who want ignorance for us.”