Posts Tagged ‘Yaşar Kemal’

PEN Journey 35: Turkey Again: Global Right to Free Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN’s work attests to the power of the individual and also to a particular vision of globalization that advocates the global right to free expression, a right that supersedes national restrictions.

In February 2005 Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s most noted writers, received threats and had his books burned by nationalist groups objecting to comments he made to a Swiss magazine while he was abroad. He referred to an Armenian “genocide.” While the Armenian community rallied to defend him, their support heightened certain nationalists’ protest in Turkey. Orhan wasn’t in Turkey at the time and hoped the turmoil would die down, but a government official in southern Turkey ordered the seizing of his books from local libraries so that they could be destroyed; it turned out later that there were none of his books in those libraries.

Novelist Orhan Pamuk and Sara Whyatt, International PEN Director of Writers in Prison Committee (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At Pamuk’s request International PEN kept quiet publicly at first. In mid-April Sara Whyatt, International PEN’s Director of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and I had lunch with Orhan in London to discuss how PEN could help if the threat escalated. I was International Secretary of PEN at the time. We agreed that publicity at this stage could exacerbate the situation; however, we explained that PEN centers could work behind the scenes by direct contacts with their governments, and PEN would be prepared to step into public action should the need arise.

Pamuk intended to stay outside Turkey until late April/early May, but then he would be returning home to Istanbul. Sara stayed in touch with him and shared a plan for action if the threats resumed on his return. Meanwhile we told him PEN would continue to lobby for a change in the Turkish Penal Code that allowed the charges. Key PEN centers, who had good relations with their own governments, and centers from countries with influence in Turkey would make approaches. London’s WiPC would make similar approaches to Turkish officials in Ankara and also through mechanisms at the United Nations, OSCE, and the European Union (EU). At the time Turkey was hoping to become a member of the EU and was attempting to align its judiciary codes with those required by the EU. PEN also worked with the International Publishers Association .

PEN prepared a statement on the situation in Turkey from early 2005 and kept it updated with news and recommended actions for the over dozen PEN centers ready to respond on this case. There was also press guidance should the centers receive queries. Meanwhile PEN continued to work on the other cases of over 70 writers and intellectuals charged or in prison in Turkey, which had long been a country with a revolving door of writers harassed, detained, attacked and sent to prison.

On April 1, 2005 World Peace Day the Turkish press reported:

The investigation against author Orhan Pamuk due to this statement saying, ‘One million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds were killed’ [in Turkey] has ended with a case in which he is accused of violating article 301 of the new Penal Code (same as famous article 159 in the former one) “Insulting Turkish nationality” and with the demand of being imprisoned between six months and three years. The first hearing will take place at Istanbul Sisli No. 2 First Instant Criminal Court on December 16, 2005.

The Public Prosecutor claimed that Pamuk’s remarks in Switzerland’s Das Magazin were an infringement of Article 301/1 of the Turkish Penal Code which states that “the public denigration of Turkish identity” is a crime and that those found guilty should be given sentences ranging from 6-36 months.

With threats renewed by the Public Prosecutor and a lawsuit filed against Pamuk that could result in a three-year prison term, Orhan finally gave PEN the green light to launch its campaign. PEN centers mobilized globally, including in Turkey.

“It is a disturbing development when an official of the government brings criminal charges against a writer for a statement made in another country, a country where freedom of expression is allowed and protected by law,” I noted at the time.

Pamuk’s hearing in December, 2005 was approximately ten years after renowned Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal had been called to trial on similar charges in January 1995. Pamuk told a colleague he would underline two things in his statement:

1. What I said is not an insult, but the truth.

2. What if I were wrong? Right or wrong, do not people have the right to express their ideas peacefully in this Turkey?

Eugene Schoulgin, PEN International Board Member and Müge Sökmen (Turkish PEN) at WiPC Conference, Istanbul, 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the judicial hearing, PEN members came to stand witness to the proceedings, including WiPC Chair Karin Clark, Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar, and International PEN board member and former WiPC Chair Eugene Schoulgin. Armored police officers escorted Orhan as protesters hurled a barrage of eggs and jumped on the car, punching the windshield.

PEN’s observers reported at the time: “The scenes around the first appearance of Orhan Pamuk before Sisli No. 2 Court of First Instance on 16 December 2005 at 11:00 were marked by constant shouting and scuffling turning ugly and violent at times. As those attending the proceedings left the court, eggs were hurled along with insults from the nationalists and fascists among the crowd lining the pavement across the street. This in full sight of the national and international media which had turned out in full…

“The courtroom was packed with well over 70 people—among them famous Turkish writers such as Yaşar Kemal and Arif Damar, and representatives of the European Parliament, several diplomats, members of Turkish and international freedom of speech organizations. The aggression and heckling inside and outside the court did not abate…”

The session ended after an hour and 15 minutes with an adjournment because the Ministry of Justice said that it needed more time to decide on the legal basis of the trial.

Hearing the news of postponement, International PEN President Jiří Gruša declared, “It is unbelievable that Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s best known and eminent authors, is in this situation. What it indicates is a complete disregard for the right to freedom of expression not only for Pamuk, but also for the Turkish populace as a whole. This decision bodes ill for other writers who are being tried under similar laws.”

He added, “PEN demands that the trials against all writers, publishers and journalists be halted and that the laws under which they are being tried be removed from the Penal Code. We also call on the Turkish authorities to put a definitive end to the penalization of those who exercise their right to freedom of expression.”

Hrant Dink, Journalist and Editor-in-chief Argos and Hilde Keteleer (Belgian Flemish PEN) at PEN WiPC Conference in Istanbul, Spring 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the time there were 14 other writers, publishers and journalists on trial under the newly revised “insult” law for criticizing the Turkish state and its officials. These included Ragip Zarakolu, publisher of books by Armenian authors and Hrant Dink, editor of an Armenian language newspaper, who was assassinated two years later.

For Pamuk the charges were dropped in January 2006, though on a technicality rather than on legal grounds protecting freedom of expression. The widespread opposition to Pamuk’s prosecution by PEN and other organizations succeeded, but as Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar noted in The New York Times: “There are many people abroad who fail to see beyond Orhan Pamuk’s trial. Saving a writer like Orhan Pamuk from prosecution may stand as a symbolic example on its own. But it is not an overall resolution for other intellectuals and writers that still face similar charges in Turkey.”

In March 2006 Orhan was the featured guest at PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee’s biennial conference held in Istanbul, hosted by Turkish PEN.

Writers in Prison Conference Istanbul 2006. L to R: Karin Clark (International PEN Chair WiPC), Sara Whyatt (Director WiPC), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary International PEN), and Sara Wyatt (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

On October 12, 2006 Orhan Pamuk won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

It could be said that the case of Orhan Pamuk signaled a long ride to the end of Turkey’s potential membership in the EU. In September 2006 the European Parliament called for the abolition of laws such as Article 301 “which threaten Europe’s free speech norms.” In 2008, the law was reformed, but according to the reform, it remained a crime to explicitly insult the “Turkish nation” rather than “Turkishness,” and in order to open a court case based on Article 301, a prosecutor was required to have approval of the Justice Minister; a maximum punishment was reduced to two years in jail. In November 2016 the members of the European Parliament voted to suspend negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns. In February 2019 the European Union Parliament committee voted to suspend accession talks with Turkey.

Turkey continues to be one of the most problematic countries for writers, especially on certain topics. While Turkey’s Penal Code relaxed for a while, allowing more space and freedom for writers, in the last years, the code and its execution has grown more onerous than ever.

*****

In that spring of 2005, I attended an event celebrating Press Freedom Day (May 3), hosted by Italian PEN in Venice. There I shared testimonials from writers on whose behalf PEN had worked. I share these again here:

** Cuban journalist and poet Jorge Olivera Castillo was conditionally released from prison in December 2004 after serving 20 months of an 18-year sentence. He wrote:

Your solidarity has been a light in the darkness. Thank you for having elected me as an Honorary Member…[I send] to all of you my gratitude for your messages of support and your unflagging concern.

** Nkwazi Mhango, Tanzanian journalist in exile, wrote:

Believe it or not tears are gushing as I am writing this message. No way in whatsoever manner my family and I can reciprocate your love and commitment to our plight. THANKS AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN MORE.

** On a sadder note the following was received from Tunisian internet writer Zouhair Yahyaoui, who died suddenly in March 2005 from a heart attack after he’d been released from prison:

Your email gave me once again a lot of hope for a better future in my country at a time when the dictatorship uses all illegal and barbaric means to make us give up and abandon all forms of protest…The fact that I continue to struggle to obtain our right to freedom of expression, here in Tunisia, is thanks to support of members of International PEN and other international organizations. Thank you again to you, to the Writers in Prison committee of International PEN and to all the PEN clubs all over the world who have supported me enormously during my imprisonment and who continue to do so.

** And from Chinese writer Jiang Qisheng:

… I am not a remarkable person. I am just an ordinary guy who did something extraordinary because it was the right thing to do…If my own case has any special significance it is only that it forces people to face a highly embarrassing fact—the fact that even now, in the dawn of the 21st century, a Chinese citizen can be imprisoned for what he says.

** I ended with a passage from the book This Prison Where I Live, the collection of prison writings drawn together by International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In the afterword Malawian poet Jack Mapanje, who himself was in prison during the autocratic rule in his country, tells how bits of news managed to get smuggled into him in his concrete cell filled with spiders and cockroaches, scorpions and bats and bat droppings.

I found the note, unusually fat…I found a bulletin of typed world news and two poems by Brecht…Pat also enclosed two honorary membership cards from International PEN’s English and American centers, issued in London and New York respectively. They each bore my name. I had been made a member of PEN. Well, well, well!…

Then there was a cutting from Britain’s Guardian newspaper. Lord Almighty! A picture of Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, Antonia Fraser, and other members of English PEN reading from my book of poems in protest at the Malawi High Commission in London! It must sure have an effect, I thought. Ten thousand miles away, among the cockroaches of the prison where I lived I felt utterly humbled. Shattered. Such generosity, such warmth I surely did not deserve. All for one slim volume of poems? Why hadn’t I written more poems? I was dumbstruck. Despair vanquished. ‘I am belonged,’ I heard myself whisper.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN Journey 34: Diyarbakir and Beyond—Finding Byways for Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN has always been about building bridges, finding the byways of fellowship among writers whose currency is language and imagination and whose hope is that even with radically different histories and backgrounds, writers might find a way to sit down across a table from each other and share stories and listen to each other and thereby have a beneficent influence on the way they and their societies see themselves and others.

It is an idealistic goal that has been battered in PEN’s hundred year history, and yet the organization continues; the dialogues continue, and writers from over 100 countries continue to meet and talk, even from countries whose governments have not found peace in decades. There have been moments of seeing that optimism realized, at least for a time, and also seeing it smashed.

The next section of these PEN Journeys covering the years 2004 (PEN Journey 33) through 2007 (August) will focus on my years as International Secretary of PEN International. I will travel through events chronologically, the number of events increasing considerably as the role demanded. I will try to knit these together as we continually try to do as an organization.

International PEN Seminar on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

In January, 2005 we held our first board meeting of the year in Vienna where PEN President Jiří Gruša had recently taken up the position as Director of the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna which hosted us. The formal board meeting itself took place in the basement of the hotel restaurant where we were staying. Around the table in the cozy space where we sat on chairs and on a long booth was PEN’s diverse board from Algeria, Colombia, France, USA, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Croatia, Australia, Norway and Japan. The search for an executive director, the new financial and employment systems going into place in the office, an upcoming meeting in Stavanger, Norway with the old Cities of Asylum Network, and an upcoming meeting in Diyarbakir, Turkey with Kurdish and Turkish PEN—all populated the agenda as did the omnipresent discussions on fundraising.

For me, the imminent departure of my Marine son from the combat zone in Iraq hovered in the corner of my mind. We were staying at a pension hotel with small rooms—single bed, dresser and nightstand; I could almost touch the walls on both sides. Outside it was snowing. I’d come to Vienna unprepared for the snow and had bought at a sale a large puffy yellow coat that now draped across the bed for warmth. At night in the dark as I fell asleep, I thought about my son and one night dreamed a desperate dream. Then the phone rang; it was 1:30 in the morning. My husband’s voice woke me. “Wheels are up!” he declared. “They are on their way home!” I still remember the moment, lying there in the dark, snow glistening in the light through the small window and feeling as though the walls had suddenly expanded and a weight lifted that I hadn’t been fully aware I was carrying. The memory…the snow, the Cathedral we passed each day in the square and at dusk in the evening, the puffy yellow coat…

I was wearing that same coat as snow fell later that month in Washington, DC the day my son finally pulled into our driveway. I was sitting on the front porch swing in the snow waiting for him, thinking about the hotel room in the dark, the restaurant basement where we helped craft a conference for writers from the hostile parties in Turkey and another to find sanctuary for writers fleeing oppression—all these memories are wrapped together in a moment of return and of the spirit lifting and life opening a corridor to walk down.

Czech PEN 80th Anniversary in Louvre Cafe where PEN members met in 1925. L to R: Playwright Tom Stoppard, PEN Int’l President Jiří Gruša, Czech PEN President Jiří Stránský.

The next meeting I attended that winter on February 15, 2005 celebrated the 80-year anniversary of Czech PEN. In Prague Jiří and I toasted the endurance of his PEN Center which had been founded by Karel Čapek and 37 Czech writers on that day in 1925. Czech PEN had survived the Second World War, the Cold War, the Soviet occupation and finally the liberation. Former prisoner, playwright and PEN member Václav Havel had become President of the country and his good friend and also prisoner Jiří Gruša was now President of International PEN. Under the auspices of the Minister of Culture, we met with Havel and playwright Tom Stoppard, himself Czech, and Jiří Stránský, President of Czech PEN at the Louvre Café where the original PEN gathering had taken place. Later, the Mayor of Prague hosted a reception with Czech PEN members in the Old Town Hall where he opened an exhibition celebrating “Eighty Years of the Czech PEN Club.”

The following week Writers in Prison Director (WIPC) Sara Whyatt and I traveled to the city of Stavanger, Norway which sat on the sea with a harbor and ships at dock. The Stavanger meeting brought together PEN and members of the now disbanded International Parliament of Writers, an organization founded after the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. The Parliament of Writers had developed a program to house writers in cities of asylum, but the Parliament of Writers no longer functioned. Many of the cities, however, still wanted to continue their hospitality for writers at risk. Stavanger itself hosted writers, including poet and novelist Chenjerai Hove, who’d been president of Zimbabwe PEN until he’d had to flee the government of Robert Mugabe. Hove was a fellow at the House of Culture in Stavanger until he passed away in 2015.

Stavanger, Norway, February, 2005 setting for birth of International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN)

Helge Lunde, director of the Stavanger International Festival of Literature and Freedom of Speech convened PEN, representatives from the old Parliament of Writers and representatives from some of the cities that wanted to continue the program. In a several day meeting, the outlines of what would become the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) were laid down with PEN as the vetting organization for applications and also a source of hospitality when writers arrived in their new temporary homes. ICORN remains active today in partnership with PEN in over 70 cities which promote and protect freedom of expression and host writers and artists at risk by providing housing, an income, literary arenas, scholarships and grants. PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and ICORN regularly hold biennial meetings together.

Writer Liu Binyan, a founder and first President, Independent Chinese PEN Center

The following weekend at Princeton University the relatively new Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), founded in 2001, honored Liu Binyan, one of its founders and first President. ICPC’s members live both in China and abroad. The PEN Center gave them the ability to talk with each other and hold programs together, often in Hong Kong. Because of his writing and criticism of the Chinese Communist Party, especially after Tiananmen Square, Liu Binyan had not been allowed to return to China after an academic stay in the U.S. Though he never saw China again, in the U.S. he wrote and worked as Director of Princeton University’s China Initiative. (Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo was also a founder of ICPC and its second president.) At the dinner at the Princeton Faculty Club, ICPC members and China scholars presented Liu Binyan the book Living in Exile, written by distinguished essayists in China and abroad and dedicated to Liu who had spent considerable time in detention and in and out of labor camps. Later that year Liu Binyan passed away at his home in New Jersey.

In March “The International PEN Diyarbakir Seminar on Cultural Diversity” convened the largest and most ambitious conference that quarter in the primarily Kurdish southeast of Turkey. For years the Writers in Prison Committee had focused on cases in this dangerous region where fighting between the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and the Turkish military had resulted in multiple imprisonments and killings. However, a rapprochement appeared to be expanding between the government and Kurdish citizens. In this space, PEN International had been working with Kurdish PEN and Turkish PEN to prepare this historic meeting of the two centers, along with PEN’s leadership of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC). For the first time Kurdish writers and Turkish writers would speak side by side from the same stage in Kurdish and Turkish with translations of each language.

Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jane Spender (PEN International Program Director), Carles Torner (Vice Chair Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee).

My predecessor as International Secretary Terry Carlbom had been instrumental in the planning, and we all agreed he should continue as coordinator of the seminar. Seventy delegates from a dozen countries gathered in the ancient city of Diyarbakir/Ahmed for five days. Diyarbakir dated back at least 5000 years, one of the oldest cities in the ancient land of Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Later it was dominated by Persia and by Alexander the Great. Because of its strategic position, Diyarbakir’s sovereignty changed many times, was part of the Roman empire, later conquered by the Arabs in 639, by Tamerlane in 1394; the Ottomans conquered in 1515. Diyarbakir continued through cycles of battles for control.

Old Diyarbakir was a standard Roman town circled by a wall, the stones of which still stood. The black basalt wall was said to be second only to the Great Wall of China. Within the walls a labyrinth of cobbled streets and alleyways unfolded, leading to towers where we could see the rivers and gardens and the city’s mosques and street life below, where caravan travelers used to stop on the silk road.

Before the conference began, PEN International Program Director Jane Spender and I explored the twisting paths and shared black tea in a central plaza with Carles Torner, vice chair of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee. As an American whose national history extended back barely 400 years, this accumulation of history in the streets and walls and buildings was mind-bending. In stones, in ideas…where did history reside and how did it evolve?

On the first evening Diyarbakir’s Lord Mayor Osman Baydemir greeted us at the Town Hall for a Newroz (New Year’s) reception. I thanked him on behalf of PEN for all he and the city had done to support this seminar. “It is a treat for us to visit one of the world’s oldest cities, with a history that could occupy the imagination of a community of writers like us for years to come,” I said. “Central to the Charter and ethos of PEN is a celebration of the universal which binds us as human beings and of the diversity which distinguishes each individual—the specific history, language and culture. It is our challenge and our aspiration as writers and members of PEN to provide the forums where cultures don’t clash but communicate. That is what we hope to do here in Diyarbakir.”

The first full day of the seminar we spent at the Newroz Festival. Our delegation was seated in an honored place in the bleachers which turned out to be behind the mother of Abdullah Öcalan, one of the founders and leaders of the PKK who was currently in prison. On the grounds in front of us spread thousands/ hundreds of thousands—some said a million people—celebrating the Kurdish new year, a time that coincides with the March equinox. Terry Carlbom and I were soon escorted to the main stage where we stood looking out over a sea of people as far as we could see, many in colorful local dress. Because PEN is specifically a nonpartisan/nonpolitical organization, we felt some ambivalence at the appearance of being swept into the Kurdish cause; on the other hand, the experience was one I won’t forget. The day was celebratory without violence. If there were political speeches, they were not translated for us, and we were accompanied by our Turkish colleagues who also attended.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference on Cultural Diversity, 2005. L to R: Mehmed Uzun and Dr. Zaradachet Hajo (Kurdish PEN), Kata Kulavkova, (Chair, PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), and Üstün Akmen, Turkish PEN

That evening in opening the conference, I noted, “In Diyarbakir/Ahmed this week we’ve come together to celebrate cultural diversity and explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.”

The official program began with the Lord Mayor and the President of Kurdish PEN Dr. Zaradachet Hajo and the President of Turkish PEN Mr. Üstün Akmen and a keynote speech by Kurdish author Mehmed Uzun. The following evening Turkish writer Murathan Mungan delivered an introductory address to a public gathering.

At the conference itself Kurdish and Turkish writers, poets, publishers and translators shared history and literature across their linguistic borders. Through discussion and readings and performances, they addressed the importance of cultural diversity as a value in a culture of peace.

Renowned Turkish/Kurdish novelist Yaşar Kemal, former president of Turkish PEN, had been invited but was ill and sent a message instead. He noted that the world was going through a difficult period and was faced with terrible destruction. He asked, “What makes human beings? Love, compassion, peace, friendship…Human beings are the only creative beings in the world.” Local cultures are being destroyed and with that is the destruction of languages and art and values, he said. In life and death we have to stand against a terrible destructive force in favor of local and national culture. “I believe your meeting will be successful,” he predicted.

Kata Kulavkova, Chair of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee emphasized the importance of the capacity to imagine, the importance of cultural memory and openness to dialogue. “Europe needs all identities, including Kurdish identities,” she said, noting that every culture is the center of the world for itself. “Turkish and Kurdish culture depend on each other to promote Turkish/Kurdish universal culture.”

Hüseyin Dozen of Kurdish PEN noted that literary translation helps a language to flourish; languages that are not standardized are enriched by literary translation which is an art rather than a scientific discipline. As far as languages that have no official status or have been prohibited, oral literature plays a central role, and the work of a translator must not neglect this kind of literature in his work.

PEN Vice President Lucina Kathmann led a discussion on “Bridging Borders” among women writers. Müge Sökmen of Turkish PEN moderated a discussion on Diversity and Literary Translation; Kurdish PEN member Berivan Dosky moderated a discussion on Cultural Diversity and Peace; Turkish PEN’s Vecdi Sayar led the discussion on Cultural Diversity and Dialogue, and Aysu Erden of Turkish PEN moderated a panel on Cultural Diversity and Linguistic Diversity.

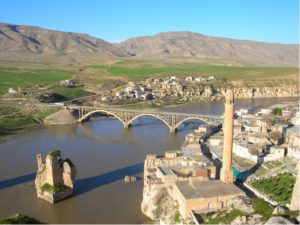

PEN trip to ancient town of Hasenkeyf, Turkey, 2005 including PEN International and Turkish and Kurdish members

One of the highlights of the conference was a visit to Hasankeyf, reputed to be the oldest continuing settlement on the planet and a cradle of civilization. Built into the sandstone cliffs in southeast Turkey, Hasankeyf had yielded relics that dated the site even earlier than the 12,000 years recorded, perhaps as old as 15,000 years. This Kurdish town of southeast Anatolia was threatened by a dam the Turkish government planned to build on the Tigris River. The Ilisu Dam would drown the town as the water was diverted and eventually would submerge Hasankeyf under as much as 400 feet of water.

Lunch in a cave in Hasenkeyf, 2005, including PEN International representatives Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender and Lucina Kathmann

As we journeyed up the stone steps to the ruins of Hasankeyf Castle and later as we ate lunch in a cave, then bought small souvenirs from children who lived in the town, our delegation fell in love with the setting and the people. Several of us returned home and began writing about Hasankeyf in an effort to preserve its heritage. We were not alone. Worldwide protests to save this ancient site had been lodged, and the dam had been delayed. I set a google alert so that every time there was mention of the Ilisu Dam, I would know. Lucina Kathmann and I began exchanging latest news.

In spite of worldwide protests, the giant Ilisu Dam was completed after many delays in July, 2019. It began to fill its reservoir, tapping water from the Tigris River and diverting it from Iraq. The rising water levels are now slowly submerging the town of Hasankeyf, flooding the area which had been settled for millennia. The population for the most part has had to move. The waters have risen 15 meters and continue to rise around 15 centimeters per day, according to a February report by Reuters.

Hasenkeyf, Turkey, March 2005 during PEN Conference on Cultural Diversity, before the Ilisu Dam flooded the region.

Turkey’s rapprochement with the Kurds has also taken a turn away from the opening and the cultural diversity we celebrated in the 2005 Diyarbakir Seminar. But literature was exchanged there; friendships were made, and the dialogue among PEN members continues. Individual by individual has always been the strength and the modus operandi of PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 35: Turkey Again: Global Right to Free Expression

PEN Journey 19: Prison, Police and Courts in Turkey: Initiative For Freedom of Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

We sat on the ferry drinking strong Turkish coffee then handing over the emptied cups to a woman who read fortunes from the pattern of the leftover coffee grounds. As we huddled in the wind off the Sea of Marmara en route to the prison in Bursa, we speculated who among the passengers was following us. We were assured we were being followed.

Program for Initiative for Freedom of Expression Gathering, March 1997

I came to Turkey in March 1997 as the returning Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WIPC) (PEN Journey 18). I was heading a delegation of 20 PEN members from 12 countries. We’d arrived to support Turkish PEN, the Turkish Writers’ Syndicate, the Literary Writers Association and the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in the first Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression. We had signed on as “publishers” to an abridged version of the book Freedom of Expression. The original book included essays by those who were in prison or facing charges for their writing, particularly former president of Turkish PEN, the prominent novelist Yaşar Kemal. He was tried for an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel. (PEN Journey 17). Headlined “Campaign of lies,” the article called out the government for its human rights abuses, particularly its treatment of the Kurds.

Arthur Miller letter to Yaşar Kemal, March 1997

Bearing a letter from Arthur Miller, who knew Kemal and had himself come to Turkey with Harold Pinter in solidarity a dozen years before, I was among the 141 “foreign publishers” of the booklet Mini Freedom of Expression. This book contained a paragraph from each article published in the larger book. We joined the 1080 Turkish “editors” of the larger volume who included writers, theater actors, politicians, painters, cinema actors and directors, cartoonists, musicians, trade unionists, academics, lawyers, architects and others. The Turkish Penal Code made it a crime to re-publish an article that had been defined as a “crime” so that the publisher as well as the writer was charged.

The “publishers” had presented themselves before the State Security Court and faced charges of “seditious criminal activity.” After questioning the first 99 people, the prosecutor demanded the accused be tried under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law and Article 312 on “disseminating separatist propaganda.” After six months only 185 of these individuals had been questioned and brought to trial. If these individuals were given the usual 20-month jail sentence, that would mean ten popular television programs would have to be canceled because their stars or directors would be in prison; five series would have to find new stars and change their story lines. The media would lose over 30 well-known journalists; 15 popular columns would be left blank. Eight professorial chairs would be left vacant, and universities would require new teaching staff. Theater stages and film sets would require many other artists, directors, musicians, etc., and 20 new books about prison life would be added to literature if every author wrote.

Turkey already had over 200 writers either in prison or entangled in legal processes, more than any other country. This protest initiative was unique and creative. The challenge to the court was to bring charges against so many. The State Prosecutor had dropped charges against the foreign participants on the grounds that he wasn’t able to bring us to Istanbul for questioning though the Turkish citizens who had prepared and distributed the booklet could be tried. The organizer of the initiative Şanar Yurdatapan suggested we come to Istanbul and challenge the prosecutor. Though PEN members were willing to come to support their Turkish colleagues, no one wanted to end up in a Turkish prison.

“No one will go to prison,” Şanar assured. The prosecutor had to act within six months, and even in the unlikely event charges were brought, we’d go home before a trial, and there was no extradition from the US, UK and many other countries because no such “offense” existed under their laws. Unlike organizations such as Greenpeace, PEN was not a direct action organization. PEN dealt in words, protest letters, diplomacy, meetings, on occasion candlelight vigils outside embassies and stories in the media. But Şanar, who was a song writer, civic activist, not a PEN member, instinctively understood the dynamics of nonviolent direct action and understood how to get attention and make the point that the Turkish laws were unjust and unfairly administered.

On our first day, which was Women’s Day, we joined the Saturday Mothers’ rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members. The gathering had been held every Saturday for a year and a half at Galatasaray Square, ten minutes from our small hotel in Taksim. The crowd of mothers and children held pictures and signs of their loved ones, mostly Kurds, who had been taken away, assumedly by the government and likely killed. On the edges of the crowd police in riot gear gathered but didn’t interfere. Meeting at Galatasaray Square is now banned for Saturday Mothers by the Ministry of Interior since August 25, 2018. They still keep the rally at Human Rights Association branch in one of the back streets.

Saturday Mother’s Rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members.

From there a number of us went to a women’s rally where hundreds of Kurdish women in traditional dress marched with banners shouting, “We are mothers; we are for peace! Mafia is in Parliament; students are in prison.” Along the route men cheered and dozens of police lined the road frisking and checking bags. This was the last weekend of a 40-day protest all over Turkey. At 9pm every night people around the country turned out their lights or blinked their lights and shouted out their windows and in the street, “Go Away!” in protest over the government. The idea was that people would have one minute of darkness to get years of light. At dinner that Saturday evening we watched as the streets filled with shouting and the lights in restaurant blinked on and off.

Women’s Day march of Kurdish women with police positioned along the route.

The trip to Istanbul was my first of what would turn out to be dozens of visits to Turkey over the years for PEN, for other organizations, and for family. In 1997 the times were tense; soldiers with their weapons and machine guns were stationed at the airport; armed police were on the streets; we were followed; the phones at the hotel were likely tapped. It was difficult to imagine then that it would get much better in the following decade as it did and then much worse in recent years. I’m not sure today we could hold such a gathering with confidence.

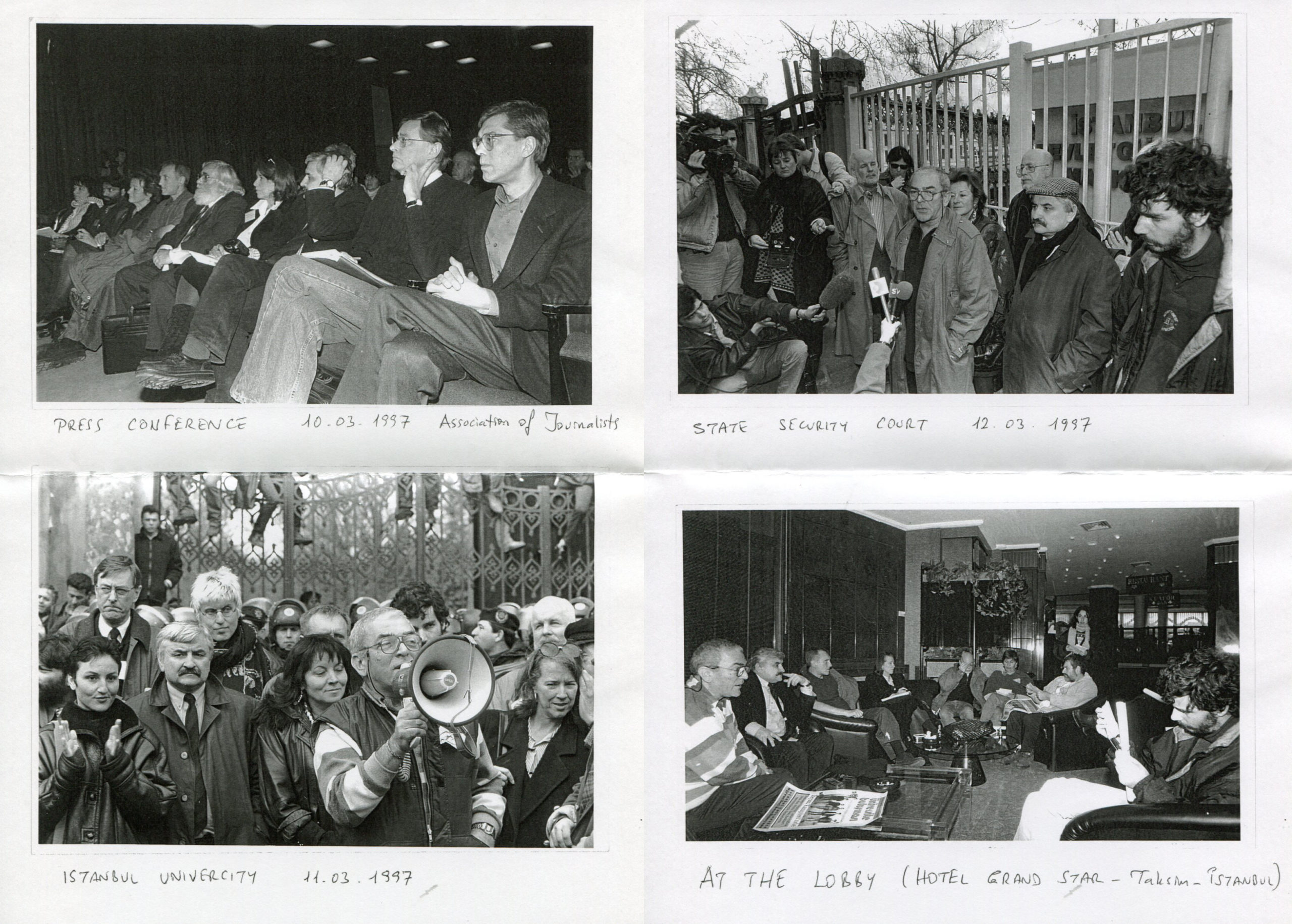

Throughout our visit we were covered by the press, including two visits to the State Security Court. In 1997 the legal way to meet publicly was to hold a press conference so we spent our days in press conferences, including one at the Journalists Association. Because I was Chair of the WiPC, I was often the one explaining why we were there. I emphasized that we had come out of respect for Turkish literature and writers. We had not come to break Turkish laws; we did not consider editing a book a crime. We were there to uphold the international covenants that Turkey had signed, approved and became a party to: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 19), Article 19 of the UN Convention on Civil and Political Rights and Article 90 in the European Convention on Human Rights. We noted that Article 90 in Turkey’s own Constitution declared that no law should supersede these international covenants.

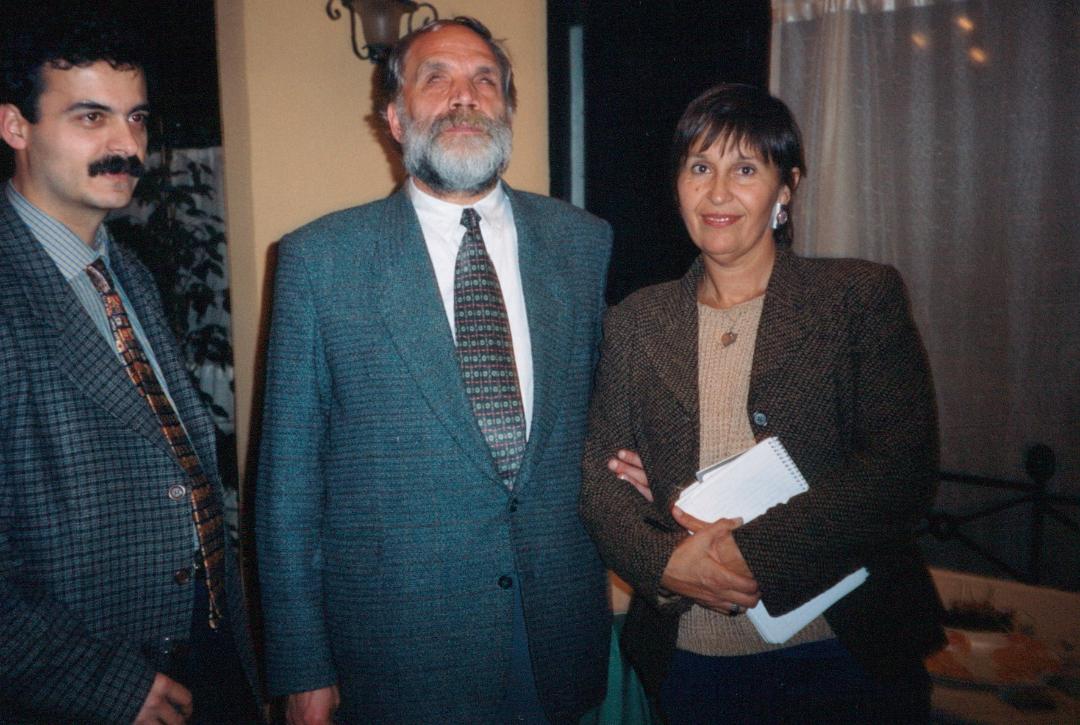

Our PEN delegation included representatives from Canada (Quebec), Finland, Germany, Holland, Israel, Mexico, Palestine, Russia, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States and Turkey. The delegates included James Kelman, Booker Prize winner from Scotland and Turkish writers including Yaşar Kemal, Orhan Pamuk and others.

PEN members from 12 countries join Turkish colleagues for dinner at the first Gathering of the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in Istanbul, March 1997

On Monday we started the day at the State Security Court where Şanar petitioned the prosecutor for an appointment to question one delegate who had to leave early. Because the prosecutor didn’t want to bring charges against “international editors”, an act that would bring international attention, the “Turkish editors” could use this failure as further evidence of the unfair nature and application of the law when they took the case to the World Court. We approached the State Security Court again on Wednesday, when the prosecutor actually locked the gates and wouldn’t see any representative of our group. In the end nine of us—from USA, England, Scotland, Finland, Holland, Sweden, Canada (Quebec), Mexico and Russia—signed a form which said, “I accepted to be one of the collective publishers of this book willingly and I am aware of the legal responsibility. I have nothing else to say.” These forms were then sent registered mail to the prosecutor.

Two small groups visited prisons and the prisoners of conscience, including Dr. İsmail Beşikçi and his publisher Ünsal Öztürk in Bursa and journalist Işık Yurtçu in Adapazarı prison. Louise Gareau-Des Bois from Quebec PEN went to the Adapazari prison and was able to visit with Işık Yurtçu.

Kalevi Haikara from Finland and I went with Şanar on the ferry to the prison in Bursa where we met Ünsal Öztürk’s wife Süreyya. We waited and waited and talked together in the bleak courtyard with grey concrete walls rising around us topped with barbed wire, with guard towers looming over us. We went to the pink concrete building of Bursa Prison with a shield on the door “Ministry of Justice Bursa Special Prison” and waited there too. But we were not allowed to see İsmail Beşikçi, the noted Turkish sociologist and philosopher who wrote about the Kurds history and living conditions. He was one of the few non-Kurdish writers in Turkey speaking out about the treatment of the Kurds. At the time he was also one of the longest serving prisoners. He’d been sentenced to over 100 years though he was released from jail two years after our visit. Of his 36 books, 32 were banned in Turkey.

Kalevi Haikara from Finish PEN and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, WiPC Chair and member American PEN outside prison in Bursa, along with Süreyya, wife of prisoner Ünsal Öztürk (middle picture) and in conversation at Bursa Prison (far right picture.)

We were also not allowed to see Ünsal Öztürk, Beşikçi’s publisher, who had completed more than a three-year sentence. We met with the press which had gathered. We paid the outstanding fine against Öztürk with funds raised from Turkish writers, artists and many of the visiting PEN members. Öztürk was released the following day though there remained 30 outstanding cases against him, 62 charges waiting to be brought to court, all relating to Beşikçi. Every time he published a book, a charge was brought, but he kept publishing. Öztürk and his wife joined the conference.

The following day we attended the Justice House hearing of the “Kafka Trial.” When one editor of the Freedom of Expression book—actor Mahir Günşiray—faced the judges, he’d read a paragraph from Kafka’s The Trial. The paragraph offended the judges, and they brought a civil suit against him. Sixty-five other writers and artists signed on and said they also endorsed the reading of Kafka and should thus be guilty too. We all piled into the small room where the defendant Mahir Günşiray and his lawyer and the judge met. The hearing was the second or third for him, but with the room full of observers, the judge again postponed the proceedings.

At hearing of “Kafka Trial” in the Justice House

Many of us went next to Istanbul University to participate in a Forum on Freedom of Expression. However when we arrived, hundreds of students were protesting in the plaza, surrounded by riot police with shields. The situation was tense. In Ankara students had recently been arrested after they’d unfurled a banner in Parliament challenging the 300% tuition increase at state universities. The student protesters there were tried with the demand of 18-year prison sentences. The students at Istanbul University asked if we would speak at the rally. None of us were prepared for this potentially explosive scene. The writers who’d come to speak on freedom of expression asked me to talk for the group, all except Sascha from Russian PEN who also wanted to speak. Sascha, Şanar and I addressed the crowd. I emphasized that we were there to uphold the right for free expression, not to take a side with any particular party of government or to take sides on how education was financed in Turkey, but to insist that individuals should have the right to discuss, debate and write about these issues without facing prison terms. We urged that the protest stay nonviolent. We were then ushered out through the police corridor.

Rally at Istanbul University (Includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (WiPC Chair/American PEN), Hanan Awwad (Palestinian PEN), Turkish writer Vedat Türkali, and Şanar Yurdatapan (with bullhorn).

In the evening the Istanbul Bar Association hosted us. The head of the Bar noted that the Turkish Constitution protects the state against the individual rather than the other way around as in the US. Everyone agreed there was free expression in many quarters of Turkey, but that the danger arose when one addressed Kurdish issues and Kurdish separatism and referred to the PKK.

Attending the meeting was the former PEN main case Eşber Yağmurdereli, a blind poet/dramatist, who’d served 14 years in prison. Released August 1991, he’d spoken in September 1991 at a meeting on behalf of Kurdish prisoners and had new charges brought against him. After five years he was still awaiting the resolution of that case. His passport had been taken from him. He could be sent back to prison for more than 20 years. He said he was unable to write, and if he wrote, he had to hide the writing and not publish. He earned his living now as a lawyer.

Meeting with Istanbul Bar Association. Eşber Yağmurdereli (middle) and Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN) on right.

I also met the young brother of Bülent Balta, an investigation case. Balta, a chemistry honors graduate, a Turk, not a Kurd, had agreed to edit Özgür Gündem, the Kurdish newspaper, because of his sympathies for the difficulty of the Kurds. He had no particular experience as an editor, and after only 11 days was arrested and was serving a four-year prison sentence.

That evening the protest at Istanbul University was all over the news, including pictures of me with a bull horn speaking, but my words had been translated into Turkish so I had no clear idea what it was reported I was saying.

Early the next morning I slipped out of our hotel and walked to a large international hotel nearby where I called home. I asked my husband to confirm my return flight the following day. He asked what the flight was, but I told him to check with the travel agent and confirm. Over the phone I didn’t want to give flight details. I told him what was happening, including the widespread coverage of the protest with my participation, and he told me a colleague in Washington said that the American Embassy knew I was there and warned me not to leave the hotel. I had to leave the hotel, I explained. I was leading the delegation and events were planned, including a farewell dinner on the Bosphorus.

At the final panel/press conference, I noted that I had two sons, and as I observed the young people here, especially the young police officers and the young students, I felt sorrow that these youth were set across battle lines from each other. There was so much talent and promise we had seen. For the first time in the three days of speeches and press conferences, emotion stirred in my voice and I paused for a moment. One of the headlines the following day read something to the effect: “She Cries for Turkey!”

Panel at Initiative for Freedom of Expression Conference, Istanbul March, 1997

The following morning I was to be driven to the airport, but the driver didn’t show up, and I was left to find my own transportation in a taxi. The atmosphere around the conference had slowly made each of us cautious, even slightly paranoid. As I climbed into the taxi, driven by a stranger, I remembered the fortune teller on the ferry a few days before. Proceed with caution…was that her warning? You will make friends…was that the prediction? The road ahead is fortuitous but also fraught? In fact, I no longer remembered what her fortunes were, and I didn’t believe in fortunes or scattered coffee grounds, but I left Istanbul with a strong belief in the people and a commitment to the country and to the writers and publishers and lawyers and journalists and to the young people I had met and to the promise they represented.

In years following I returned to Turkey on numerous missions for PEN and for meetings with Human Rights Watch, with the International Crisis Group, on a trip with UNHCR looking at the Syrian refugee crisis, and several trips with my oldest son who wrestled in the World Championships and European Championships in Ankara and in the World Championships again in Istanbul and also lectured in mathematics at Koc University and other universities and with my youngest son who lived in Istanbul for two years with his two young children and wrote as a journalist on the Turkish/Syrian border and has set two of his four published novels in Turkey.

PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Centre to Centre newsletter special Turkey section April 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

PEN Journey 17: Gathering in Helsingør

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

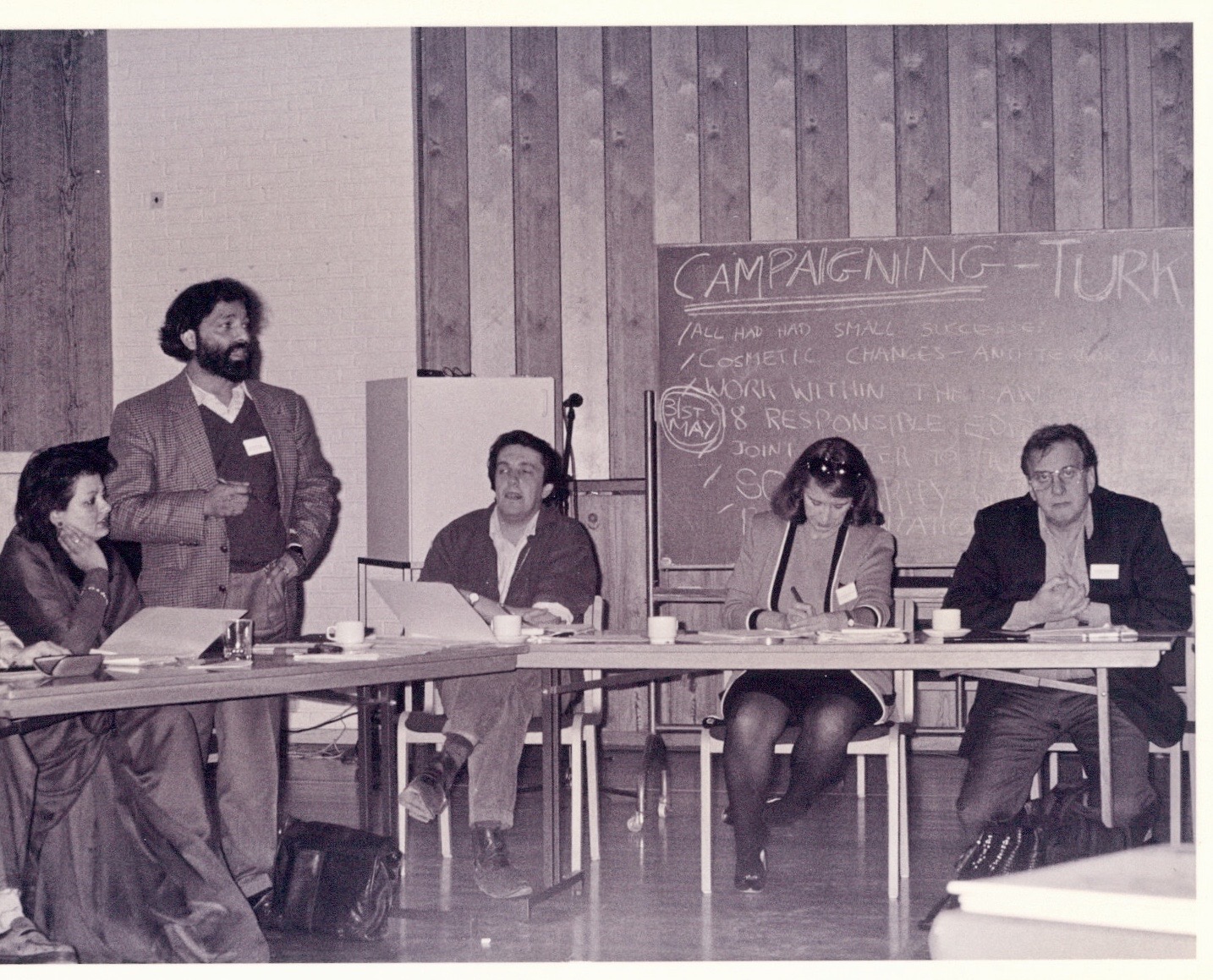

What I remember most about the gathering of colleagues from 28 countries—31 PEN centers—51 of us in all at the first Writers in Prison Committee conference in 1996 was the seriousness of purpose and intellect during the day and the fun and talent in the evenings.

Hosted by Danish PEN, writers from every continent gathered at a university in Helsingør—known in English as Elsinore, the home of Shakespeare’s Hamlet—where we met in workshops and ensemble during the day to shape and refine our work on behalf of writers and freedom of expression around the world. But in the evening we were at a small university in a small city without transportation or distraction so we entertained ourselves. Each delegate displayed talents—from poetry reading to song to dance to musical performances.

As Chair of the WiPC gathering, I’d brought none of my own writing to read and was left to exhibit meager other talent which consisted of playing a few opening bars of Für Elise on the piano and whistling tunes with my far more talented Danish and Russian colleagues. Archana Singh Karki from Nepal in flowing red dress entertained with her graceful dance; Siobhan Dowd, our Irish former WiPC director and Freedom of Expression director at American PEN, silenced us with her soulful Irish folk songs, sung acapella; Sascha, Russian PEN’s General Secretary, not only whistled robustly but recited his poetry, which I was told I should be glad I didn’t understand with its bawdy content; Sam Mbure from Kenya and Turkish/English novelist Moris Farhi also read and recited work. PEN International President Ronald Harwood joined the discussions in the day and was audience in the evening. I don’t recall if Ronnie offered his own work, but we all bonded in our mission and in our support for the talent in the room.

Entertainment in the evening: From the top left—Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Chair of WiPC)in a whistling song; Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East) accompanying Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN) in dance; Siobhan Dowd (at piano—English & American PEN) with Moris Farhi (reading—English PEN); Sam Mbure (reciting—Kenyan PEN); Niels Barfoed (reading—Danish PEN)

During the three days, we fine-tuned our methods of working on and campaigning for our main cases, those writers who were imprisoned, attacked or threatened because of their writing, often their nonviolent voice of protest against authoritarian regimes. We considered PEN’s decision-making on borderline cases such as those which included drug charges, advocacy of violence, pornography, hate speech, terrorism. These were not categories we normally took on as cases. We discussed when we might take up such a case or assign them to investigation or judicial concern. We laid the groundwork for more joint actions among centers and other organizations such as the U.N., OSCE and IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.

Round Table of the WiPC conference which included delegates from PEN centers in Switzerland, Jerusalem, Denmark, England, Mexico, Portugal, America, Norway, Czech Republic, Ghana, Canada, Australia (Melbourne and Sydney), Portugal, Finland, Nepal, Scotland, Malawi, Kenya, Ghana, Croatia, Slovakia, Sweden, Spain, Austria, Japan, Germany, Russia, Poland, Netherlands

With PEN’s WiPC staff Sara Whyatt and Mandy Garner, we set out a campaign calendar for the year, beginning with Turkey in May; China in June; Myanmar in July; Guatemala in September; Vietnam in October; Nigeria in November; Human Rights Day focus in December; Cuba in January; Rushdie and Fatwa and Iran in February; United Nations Commission on Human Rights lobbying in February/March and a return to China during the Chinese New Year in February/March; International Women’s Day in March and World Press Freedom Day in May. This campaign calendar meant that the London office would send information each month related to these foci, and PEN centers would plan programs if the campaign fit their work and the cases they had taken on.

We discussed the elements of successful missions to troubled areas and what future missions should be considered. In 1997 PEN International and Danish PEN sent representatives on a quiet mission to Cuba. We also strategized on the effect of writers observing trials in certain countries, particularly in Turkey.

Working session on Turkey Campaign at at WiPC conference: L to R: Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN), Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East), Robin Jones (WIPC staff), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair), Ronald Harwood (PEN International President)

During the conference a request came for members of PEN to sign on individually and en mass as publishers of a book in Turkey which republished an article by the famed Turkish novelist Yaşar Kemal, along with articles by other Turkish writers who were in prison because of their writing. Kemal had recently been charged because of an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel about the Kurds. The organizer in Turkey had gathered hundreds of Turkish writers, publishers, artists, and actors to sign on as publishers. They wanted to present the book and the list of hundreds of publishers to challenge the courts to bring charges against everyone. Many of us agreed to participate. This act launched a campaign in Turkey and a mission later in 1997. (Blog to come.) The independent Turkish Freedom of Expression Initiative has since gathered biennially for the last 23 years. For this kind of joint action PEN was primed to cooperate.

Finally in Helsingør the Writers in Prison Committee took a step towards opening up the election process for the WiPC Chair. My term was due to expire at the fall 1996 Congress in Guadalajara. We decided to select a nominating committee from members to find candidate(s) for the next chair rather than have the post appointed by the Secretariat in London. That process was later replicated in other elections in PEN and is standard procedure today.

Workshop: From left includes: Neils Barfoed (Danish PEN), Lady Diamond (Ghana PEN), Moris Farhi (English PEN), Sara Whyatt (WiPC Programme Director), Mandy Garner (WiPC researcher), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair at front)

Helsingør was a fitting venue for the first WiPC Conference, not only because of its literary credentials with the Kronborg Castle where most of Shakespeare’s Hamlet takes place, but also because of its historic legacy in World War II. Helsingør was one of the most important transport points for the rescue of Denmark’s Jews. A few days before Hitler had ordered that the Danish Jews were to be arrested and deported to concentration camps October 2, 1943, one of the Nazi diplomatic attaches who’d received word in advance shared the information with the Jewish community leaders. Using the name Elsinore Sewing Club, the Jewish leaders communicated with the population, and the Danes moved the Jews away from Copenhagen to Helsingør, just two miles across the straights to neutral Sweden. The Danish citizens hid their fellow Jewish citizens until they could get onto fishing boats, pleasure boats and ferry boats and escape over a period of three nights. The Danes managed to smuggle the majority of its Jewish citizens—over 7200 Jews and 680 non-Jews—across the water to safety.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 18: Picasso Club and Other Transitions in Guadalajara

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International

View on the Bosphorus: Rights in Retreat

I’m sitting on the Bosphorus today in Istanbul looking across to the Asian side over the balustrade of a European porch. I’ve been visiting Istanbul over the last 20 years for conferences, recently for visits to refugee camps and most often now to see family living here. Istanbul is one of my favorite cities, full of heart, multiple cultures, history and citizens of intellect and warmth.

But recently the atmosphere has chilled. I’ve come on this trip to participate in the launch of Human Rights Watch’s 2016 World Report which focuses on the “Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society” as causes that imperil citizens’ rights around the world. Istanbul was chosen as the launch city because it sits at the nexus of east and west, is the crossing point for millions of refugees fleeing the Syrian war and has an active civil society and free press that are now severely tested as the environment for rights deteriorates.

“Government-led restrictions on media freedom and freedom of expression in Turkey in 2015 went hand-in-hand with efforts to discredit the political opposition and prevent scrutiny of government policies in the run-up to the two general elections,” according to Human Rights Watch (HRW) 2016 World Report.

The restrictions include the investigation of Cumhuriyet newspaper for posting a report showing weapons on trucks allegedly headed to Syria. The paper’s editor Can Dϋndar and Ankara representative Erdem Gϋl were arrested and are now in jail awaiting trial. Other journalists have been arrested for criticizing the government. There have been police raids on media groups, a widespread firing of journalists perceived to be in opposition to the government, in particular to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Publisher Cevheri Gϋven of Nokta news magazine and editor Murat Çapan spent two months in jail for “inciting an armed insurrection against the government” for a report and a satirical picture of Erdoğan. Nokta’s website remains blocked by a court order. Months of pretrial detention have been handed out to those allegedly insulting Erdoğan via social media and during demonstrations.

I first came to Istanbul in spring, 1997 for the “Initiative for Freedom of Expression”, a conference that brought together PEN International and freedom of expression organizations in Europe to protest the harsh treatment of writers by the Turkish government and courts. Charges had been brought against the celebrated Turkish novelist Yaşar Kemal for an article he wrote for the German magazine Der Spiegel in which he accused the Turkish army of destroying Kurdish villages. Though he was acquitted, he is quoted as saying, “One person’s acquittal does not mean freedom of expression has arrived. You can’t have spring with only one flower. We still have to work very hard to achieve democracy in Turkey. I will continue to write these things until there are no trials against expression.” Kemal passed away last spring at age 91.

At the time activist and song writer Şanar Yurdatapan organized a publication that included Kemal’s essay and the writings of other Turkish and Kurdish writers who had been banned or imprisoned. He mobilized Turkish artists and publishers and academics to sign on as the publisher, and he asked writers from the more than 100 centers of PEN International around the world also to sign on as publisher. The publication thus challenged the government which would have to bring charges against hundreds of people as publisher. And so the Gathering for Freedom of Expression was born.

I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee during that time, and along with dozens of writers from around the world, I arrived in Istanbul for the conference. Şanar and his colleagues organized visits to prisons to try to see the many writers and publishers incarcerated, visits to courthouses to observe hearings and trials, a visit to the prosecutor’s office to insist that we too should be charged as publisher. We understood the embarrassment such would cause the government, though none of us aspired to go to a Turkish prison. The Initiative for Freedom of Expression held multiple press conferences because the only legal way to gather at that time was to have a press conference. Yaşar Kemal spoke at one of these.

There was also a freedom of expression conference called at a university where hundreds of students had mobilized in the campus square when we arrived. Many were protesting tuition hikes, not writers in prison, but the two gatherings merged. Riot police surrounded us all as we addressed the crowds.

The period of 1997 in Turkey was charged. The heavy hand of the State was palpable. The police were at every gathering. Cars followed us. In 1997 PEN International recorded more writers in prison or tangled in the judicial processes in Turkey than almost anywhere in the world except perhaps China.

But citizens were mobilizing and claiming space for expression. In the subsequent years the Initiative for Freedom of Expression and other freedom of expression and human rights organizations recorded regularly the abuses and circulated these and mobilized actions. Şanar was sent to prison because of his work and there studied the history and principles of civilian based resistance, practices he had instinctively employed. Every other year the Gathering for Freedom of Expression assembled in Istanbul, several of which I attended. Turkey could mark its progress by the decrease of the numbers of writers and publishers in prison. Until last year.

At the launch of HRW’s World Report this week, Şanar and I met again, smiling to see each other but not smiling about the state of affairs. Turkey appears to be reverting back to the ways and days of the 1990’s. Şanar has returned to song writing, still passionate, but addressing issues through music and advising (not quite on the sidelines) the next generation of activists.