Posts Tagged ‘Thomas von Vegesack’

PEN Journey 42: From Copenhagen to Dakar to Guadalajara and in Between

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Royal Danish Library extension in Copenhagen, dubbed the Black Diamond (Photo by © User:Colin / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66870365)

Arriving in Copenhagen in early September 2006, I walked along the waterfront, dodged bicycles and shared coffee and conversation with longtime colleague Niels Barfoed, former President of Danish PEN who had briefly succeeded me as Writers in Prison Chair and was an eminent Danish journalist and writer. We met at the new waterfront extension of the Royal Danish Library, dubbed the Black Diamond because of its imposing black granite cladding and irregular angles. Niels would be moderating a public meeting on Freedom of Expression in the Arab World.

PEN International’s base was broadening in the Middle East and in Africa, both regions where active centers for writers were fragile, but potentially important havens. Danish PEN was hosting a conference with a dozen writers from the Arab-speaking world, including representatives from Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Palestinian PEN, Tunisia, Lebanon and invited writers from Iraq and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), along with Danish and Norwegian PEN members and International PEN represented by Centers Coordinator Peter Firkin and myself.

The Copenhagen conference had been initiated in part as a response to the Danish cartoons controversy earlier in the year and also as an opportunity to develop PEN’s work and presence in the Middle East. PEN had a few centers in the region and interest from writers in Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, and Bahrain to form additional PEN centers and a desire to revive PEN Lebanon. Developing PEN centers in these areas was challenging given the politics and conflicts on the ground.

Ekbal Baraka, President Egyptian PEN (left) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN International Secretary (right) meeting in Cairo, 2006

The Copenhagen meetings explored common fields of interest among Western and Arab writers, networking among Arab writers and ways in which PEN could assist. Women writers in the Arab world had particular challenges, a discussion led by Egyptian PEN President Ekbal Baraka. Ekbal later became Chair of PEN International’s Women Writers Committee. Algerian PEN and International PEN board member Mohamed Magani offered to host a subsequent meeting in Algiers the following fall, along with a conference on translation. A public event in the evening showcased the work of the visiting writers.

On the final day the public conference on Freedom of Expression in the Arab World moderated by Niels included discussions on Networking in the Cause for Freedom of Media and Opinion and featured renowned Tunisian journalist and human rights campaigner Sihem Bensedrine. A discussion on Access to Information: Implications to Development was addressed by Jordanian journalist Daoud Kuttab and Danish columnist and Danish PEN President Anders Jerichow. Lebanese Writer Elias Khoury and Egyptian journalist and commentator Mona Eltahawy concluded the conference in a discussion on Publication and Powerplay in the Middle East.

The days together resulted in a loose network of these and other Arab writers and eventually led to the opening of additional PEN centers and work in the Middle East. PEN currently has Bahrain, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestinian centers as well as the Egyptian, Algerian and Moroccan Centers.

******

Anna Politkovskaya, Russian journalist assassinated, 2006

A few weeks after the Copenhagen conference, my phone rang early on Saturday morning October 7, 2006 at my home in Washington, DC. Sara Whyatt, PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee Director, was on the line. She called to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya, Russian journalist, PEN member who’d visited PEN Congresses and meetings, who’d worked for years reporting on Chechnya—had been assassinated. The report was that Anna had been shot that morning in the elevator of her apartment building in Moscow.

For seven years Anna had been one of the few reporting on the war in Chechnya despite intimidation and violence. She had been arrested by the Russian military and suffered a mock execution; she’d been poisoned while flying from Moscow to the Beslan school hostage crisis and had to turn back to get medical treatment. She had survived many dangerous encounters. But now she had been killed.

The killing of Anna Politkovskaya swept through the news media around the world as well as through the PEN world. We were stunned and deeply saddened and then began our protests and calls for investigation, along with human rights organizations worldwide. PEN honored Anna at its subsequent Congress and meetings and annually held an Anna Politkovskaya lecture on the anniversary of her death to commemorate her fortitude and inspiration.

The work in PEN was a helix of hope and pain and sorrow and hope again.

******

Dakar, Senegal, venue for PEN’s upcoming 73rd World International Congress in 2007

At the end of November Senegalese PEN hosted a meeting with African centers engaged with the planning of PEN’s 73rd Congress to be held in 2007 in Dakar. The meeting included representatives from Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Guinea, Senegal, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Ghana. It was standard practice for International PEN to visit the site of an upcoming Congress to review logistics and budgets and programs in advance, to assist and assure the Congress ran smoothly. The 73rd Congress in Dakar would be only the second time a PEN Center in Africa had hosted a World Congress. In addition to reviewing the facilities at the Meridien hotel by the ocean, the delegation met with the Minister at the Ministry of Culture and Classified Historical Heritage which was supporting the Congress.

At that meeting and throughout the Congress to come, I offered the sentiment I had drafted and memorized in French and still endorse:

“Il n’y a que quelques autres pays dans le monde ou l’ecrivain est plus honore qu’au Senegal.

“There are few countries in the world where the writer is more honored than in Senegal.”

Because Senegal’s founding President Leopold Senghor had been a poet and writer of global distinction, also a Vice President of International PEN, Senegal celebrated literature. “As a national leader, Leopold Senghor left a rich heritage and respect for African culture and writing which we hope to honor by International PEN’s upcoming Congress in Dakar,” I told the Minister.

Karen Efford, PEN Program Officer, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, PEN International Secretary, and Caroline McCormick, PEN International Executive Director, meeting in Dakar. Senegalese PEN members organizing PEN 73rd World Congress included Abdoulaye Racine Senghor, Abdoulaye Fode Ndione, Mamadou Diop Traoré, Seydi Sow, Mbaye Gana Kehe, Alioune Badara Beye, Elie-Charles Moreau, Silcarneyni Gueye, Aissatou Diop

Senegalese PEN hosted our working meetings at its headquarters where the focus was also on regional development. International PEN’s Executive Director Caroline McCormick and Program Officer Karen Efford led a “mapping” or gathering of information with each center on its activities and membership and needs in order to determine how PEN International could assist, especially with fundraising. The Centers also participated in the discussions on the programs and facilities for the July 2007 Congress.

After hours of meetings, we all went to dinner together at the local restaurant. I don’t remember the food, except there were generous plates family style. I remember the atmosphere—the bright blues and reds and yellows in the restaurant, the music, and the laughter after a long day concentrating on budgets, logistics, and translations. The planning meetings were work but also fun with friendships among the writers from the PAN Africa Network with whom I had met on numerous occasions over the past few years.

In my three years as International Secretary, I was impressed by the care of all the host centers for Congresses. The Congress in Senegal would be my last as an officer of International PEN, except for the privilege of attending as a Vice President in the years to come. The operational work and responsibility would be passed on. I had determined not to stand for a second term. I had other responsibilities that had been put on hold for three years, and I had learned it was better to leave a position when everyone wanted you to stay, than to stay too long when people were waiting for you to leave. I needed to return to being a writer and to my family and to the other organizational work I did. So Senegal would be a farewell of sorts for me. It would prove to be a grand occasion, but I am getting ahead of myself…

******

“Does Freedom of Expression Have a Limit?” “Hospitality without Borders.”—those two panels I participated in and moderated at the 2006 Gothenburg Book Fair, Scandinavia’s largest. The International Publishers Association (IPA) and International PEN had been collaborators in selecting the Fair’s theme of Freedom of Expression that year. The Book Fair reflected the Freedom of Expression theme in many of its over 2000 events for the 100,000 visitors. PEN and IPA, along with the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN), had an exhibit with a stage where events and seminars took place.

For me, it was a special pleasure to attend the Fair in Sweden where my mentor and predecessor as Writers in Prison Chair Thomas von Vegesack was a respected and now retired publisher. Thomas attended the Book Fair. I noted in my remarks that it was from Thomas I’d learned the difference between having principles and simply talking about principles. Thomas didn’t like “principles,” which meant he didn’t like paradigms of abstractions. Our role—PEN’s role—was pragmatic. It was to help writers in trouble, to be in touch with them and their families so the isolation of imprisonment was broken, to give them support and most of all to figure out where the access was within our PEN centers and within our larger freedom of expression community to pressure governments to spring open the prison doors and also to get protection for writers under death threats. (It was two weeks after the Gothenburg Book Fair that Anna Politkovskaya was assassinated.)

The world had changed since the days Thomas and I had been chair of WiPC. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s we had all been hopeful that the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the totalitarian governments would ease the situation for writers worldwide, but there were now as many writers as ever under threat. PEN’s casebook listed over 1000. There were more non-state actors. There was also a level of global communication that was only budding in 1993 when Thomas handed over the reins to me. There were new bad guys, and many of the good guys were not as good as they once were. We were in a world where freedom of expression was no longer accepted as an unqualified value.

Yet “the world is still changed by ideas and books, and writers who write them are still the main vehicle for ideas,” I concluded my opening talk.

On the panel “Does Freedom of Expression Have a Limit?” we had no easy answer. We asked if there was a personal and public responsibility to tell the truth, or at least not to lie. And who determined a lie? The responsibility of the writer was to try to find and tell the truth even if truth seemed relative at times. The question arose, who sets the limits on freedom of expression? The State? Society at large? What were those limits and penalties and were they set by fear of attack or violence or censorship?

It was generally agreed that calls for violence such as the killing of another human being set a limit on freedom of expression, especially when this call came from someone who had the power of the state to exercise the threat. An example was the fatwa on Salman Rushdie. The limit should not be on Rushdie but on the Ayatollah and the state that issued the fatwa calling for his death.

Hate speech had a limit when it urged violence as in the case of Radio Rwanda during the genocide against the Tutsis or certain broadcasts during the Balkans wars.

PEN’s Charter contained the elements of the dialectic upon which free societies were based, both the respect for other cultures in an effort to dispel race, class and national hatreds and also a commitment to protect the free and unhampered transmission of thought and ideas.

“And since freedom implies voluntary restraint, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends,” the PEN Charter concluded.

Democracies flourish only when an exchange of competing, even contradictory, ideas can occur in a battle of ideas, the panel concluded.

Novelist Moris Farhi, former WiPC Chair and PEN Vice President/English PEN

The panel “Hospitality Without Borders,” co-sponsored by ICORN, featured Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish novelist who a month later won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and Moris Farhi, also Turkish but long resident in the UK and member of English PEN. Moris had followed me as Chair of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee after Niels Barfoed’s brief tenure.

Novelist Orhan Pamuk (Photo credit: © Elena Seibert)

The previous year, Orhan had faced charges of “insulting the Turkish Army and Turkishness” because of his statement in a Swiss newspaper regarding the Armenian genocide and massacre of a million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds in Anatolia in 1919. On the panel Orhan noted how valuable it was for a persecuted writer in his home to know about the possibility of finding refuge in a safe city, even if he didn’t take advantage or was unable to leave his present situation at the time.

Moris, who’d also chaired English PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, talked about the challenges facing the host city and the community receiving a guest writer. He focused on how to make sure the writer didn’t just disappear from the literary community and the need to focus on translation and publishing strategies for the writer. It was important to help the writer establish new foundations and relationships in a new city.

I recalled the situation of Bangladeshi novelist Taslima Nasreen who had faced death threats and was given asylum in Sweden and awarded the Tucholsky prize. Taslima Nasreen’s was one of the more dramatic cases in my PEN history as she was whisked out of Dhaka in the dark of night and brought to Stockholm by Swedish PEN. That had turned out to be just one stop on a difficult journey into exile.

******

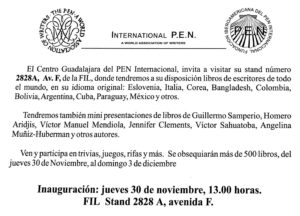

At the end of 2006, PEN Guadalajara, San Miguel PEN and the Ibero-American Foundation of PEN established a presence for the first time at the 20th Guadalajara Book Fair. The Guadalajara Book Fair was considered the most important publishing event in the Spanish-speaking world, hosting 450,000 visitors and 15,000 book professionals from over 40 countries. Officials of the Guadalajara Book Fair were eager to have a relationship with PEN in order to collaborate and “create and guarantee space in which literature of different languages cohabit supporting the freedom of opinion with words as vehicle of understanding between different nations and cultures,” according to the Coordinator of the Festival events.

At the end of 2006, PEN Guadalajara, San Miguel PEN and the Ibero-American Foundation of PEN established a presence for the first time at the 20th Guadalajara Book Fair. The Guadalajara Book Fair was considered the most important publishing event in the Spanish-speaking world, hosting 450,000 visitors and 15,000 book professionals from over 40 countries. Officials of the Guadalajara Book Fair were eager to have a relationship with PEN in order to collaborate and “create and guarantee space in which literature of different languages cohabit supporting the freedom of opinion with words as vehicle of understanding between different nations and cultures,” according to the Coordinator of the Festival events.

International PEN aspired to have a more robust presence at book fairs globally, but did not yet have the budget or staff. However International PEN supported centers’ activities at book fairs such as at Frankfurt, Gothenburg, and now Guadalajara. I visited the Guadalajara Book Fair as part of this initiative.

PEN Guadalajara and San Miguel and the Ibero-American Foundation of PEN hosted a stand at the Book Fair and offered readings and presentations of books and displayed hundreds of books from PEN members and PEN centers around the globe. On the Book Fair’s program two eminent PEN members, Vice President Nadine Gordimer and former PEN International President Mario Vargas Llosa were featured. Nadine Gordimer participated in a Literary Salon and later had dinner with PEN members. I have no notes from that dinner, but I have fond memories of the outside restaurant in the evening and the hospitality of Guadalajara and San Miguel PEN and the graciousness of Nadine Gordimer.

Photo Left: Meeting at 2006 Guadalajara Book Fair: María Elena Ruiz Cruz, Víctor Sahuatoba, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Lucina Kathmann, Luis Mario Cerda, Martha Cerda, Moisés Zamora. Photo Right: At dinner: Moisés Zamora, Nadine Gordimer, Martha Cerda, and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Martha Cerda, President of Guadalajara PEN, PEN Vice President Lucina Kathmann of San Miguel PEN and I met with Book Fair officials and assured that PEN would have a presence and partnership with the Guadalajara Book Fair in the years to come through its Latin American centers.

The visit to Guadalajara also offered the opportunity to meet with members from several Latin American PEN centers in a preliminary focus on the region and on the “mapping” International PEN would undertake of resources, programs and needs of the Latin American PEN centers before the 2008 Congress in the region.

******

At the end of 2006 PEN’s long time staff member Jane Spender retired. Jane had worked with Peter Day on the PEN International Magazine as an editor; she’d been administrative assistant to the Administrative Secretary Elizabeth Paterson and then became the Administrative Director when Elisabeth retired. She had taken on the role of International PEN Program Director when PEN hired an Executive Director. We all relied on Jane’s intelligence, good humor and patience. Jane and I had spent hours—too many hours we both agreed—toiling over just the right word on several documents. I was especially going to miss working with Jane; I have kept the friendship to this day. To celebrate the past and send her off with good wishes for the future, we surprised her by giving her a bicycle which I rode across the office and presented to her. Friends from International PEN and English PEN all gathered in PEN’s new offices on High Holborn. PEN is about people, and Jane was one of the stalwart ones.

Jane Spender retirement party at PEN offices, 2006. L to R: Sara Whyatt, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender, Caroline McCormack, Karen Efford, Terry Carlbom, Ursula Setzer, Josephine Pullen-Thompson, Francis King, Peter Day, Gilly Vincent, Jane Spender, Nawal, Karen Efford, Elizabeth Paterson

Next Installment: PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

PEN Journey 10: WiPC: Beware of Principles

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

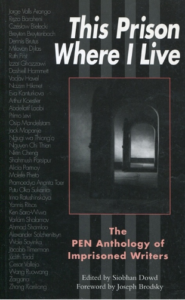

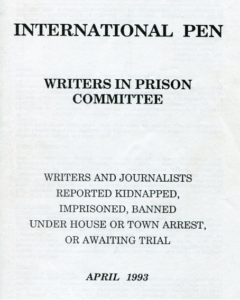

In the summer of 1993 before taking over the Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee I studied hundreds of individual cases on PEN’s list of over 900 cases which was published twice a year. I studied the regions of the world where conflict was rife, where governments were most oppressive and where writers were most threatened. I also used the time to conceive three long term projects because I knew when the job began, there would be less time for long term thinking.

First, I hoped we could gather the many poems and stories from imprisoned writers over the years and get these published into a book. In studying the cases, I came to understand that those who survived harrowing experiences were often those able to keep their imaginations alive and if possible were able to write. “We lived in Paris in our minds,” one prisoner in dire conditions inside the Western Sahara recounted. A book of these writings would celebrate and inspire and could also be used by PEN centers in their work.

Second, I wanted to convene the Writers in Prison Committees from around the world in a conference to strategize our work. PEN’s other standing committees had such meetings outside of the congresses, but WiPC never had. The PEN congresses were often filled with competing programs and those working on WiPC issues were not always the delegates. We needed to gather and plan together for several days.

Finally, I hoped to expand the roster of Writers in Prison Committees in the PEN Centers so that we could increase the number of members working and the number of writers on whose behalf we worked.

WiPC Coordinator Sara Whyatt and researcher Mandy Garner and I agreed on each of these goals. Every two weeks we met in the large airy WiPC office at the top of the Charterhouse Buildings in London or often at the tea shop across the alley. At the end of our strategy sessions we would discuss how to move forward the longer range goals. I learned an important lesson—first, a goal begins with an idea then is realized by having talented, committed people around. For me that began with Sara and Mandy, who set steps in motion. And then each project found a path forward as people arrived into our circle to help accomplish the tasks.

One day a publisher showed up in our office and asked if we had ever considered doing a book of prisoners’ writings. As a matter of fact…We quickly outlined our idea, put together a team with former WiPC coordinator Siobhan Dowd as editor, and a year and a half later in 1996 This Prison Where I Live was on book stands with selections from more than 65 writers who had been imprisoned, many of whose cases PEN had worked on, from Arthur Koestler to Cesar Vallejo, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Jacobo Timerman, Breyten Breytenbach, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Primo Levi, Wole Soyinka, Vaclav Havel, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Nazim Hikmet, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and many others, current and former writers in prison.

From This Prison Where I Live:

You took away all the oceans and all the room.

You gave me my shoe-size with bars around it.

Where did it get you? Nowhere.

You left me my lips, and they shape words, even in silence.

—Osip Mandelstam, former USSR, 1935

When we shared our second hope for a global gathering, Danish PEN offered to host the conference in Helsingor, the home of Hamlet. With representatives of PEN centers on every continent, this first WiPC conference convened in the spring of 1996. The WiPC gathering has been held biennially ever since at locations around the world. (More on this conference in a later post.)

Regarding the third goal, the number of PEN centers with Writers in Prison Committees has grown each year because of PEN members around the globe. Unfortunately, the number of cases of writers threatened, imprisoned or killed has also continued to grow, but individual cases are released.

In that summer preparing to take over the Chair, my predecessor and mentor Thomas von Vegesack gave me advice I found puzzling at first. He invoked: “Beware of principles!” Thomas was an empathetic and principled man so I was perplexed by his counsel, but over the years I’ve come to understand what he meant. He meant that declarations and statements can often keep you from seeing a way forward and from understanding how to work on a case if you get tangled in abstractions.

There are of course principles that govern our work enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These are fundamental, but Thomas was warning that it is important to understand each situation and not let rigidity, a kind of authoritarianism of principles or political correctness limit.

PEN’s Charter itself contains contradictory concepts. The Charter asserts that PEN members should “use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

At the same time the Charter notes that “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong…”

These two ideas of respect and freedom of expression have been challenged more than once, a decade ago in the case of the Danish cartoons. (More on this in a future post.)

Ultimately each PEN member has to resolve the inherent tension. Those from societies with longer democratic traditions are more accustomed to balancing competing ideas; but there are no certain answers. PEN has had lengthy discussions and debates on such questions as “hate speech”—what constitutes it, are there limits to freedom of expression—on slander and libel, holocaust denial, blasphemy.

These challenges for PEN are manifested in individual cases. Early in my tenure as Writers in Prison Chair, one such case blew up quickly, gathering headlines across the globe—the case of Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasrin. Dr. Nasrin (she was a medical doctor turned writer) had written a novel Lajja (Shame) which described the Muslim backlash against Bangladesh’s Hindu minority after the destruction of a mosque. She was also quoted (misquoted, she said) suggesting that the Koran should be revised in favor of women. An arrest warrant was issued for her; demonstrators called for her death, and at one point snake charmers in Dhaka threatened to release their cobras into the streets if she wasn’t executed. PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and PEN’s Women’s Committee took up the case, which had bizarre twists along the way.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 11: Death and Its Threat: The Ultimate Censor

PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

In fall, 1991 I went to Moscow just months after the August coup attempt in which hardline Communists sought to take control from President Mikhail Gorbachev. I hopped onto the visa of my husband who was traveling to Russia as a Visiting Scholar at the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London. I went as a writer, interested in meeting other writers. I contacted fellow PEN member and Russian translator Michael Scammell, who had previously chaired International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). Michael gave me a list of writers to contact in Moscow.

Statues toppled of Lenin and Stalin and others in park after failed coup attempt in Moscow, 1991.

My husband and I stayed in what I was told was one of the government hotels where guests were hosted but also watched. We were watched too, I’m fairly certain, though there was little for anyone to see with me. I was cautious as I made contact with the writers lest my reaching out compromise them. Only a few years before, PEN’s case list had included many dissident Soviet writers in prison. Michael and later WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack and PEN’s WiPC committees around the world had advocated for the release of dissident Soviet writers, many of whom were imprisoned in the gulags. PEN had also covertly sent aid to them and their families through the channels of the PEN Emergency Fund.

I no longer remember if I called or faxed the writers in advance. (Fall, 1991 was before an active internet.) I likely made contact when I arrived. The writers welcomed me. We met in simple apartments with old holiday cards on the mantles as decorations, a paper mobile hanging from the light fixture over one dining room table I recall, strips of newspaper stacked by the toilets in lieu of tissue. The economy was spare for these writers. They hoped for change and for freedoms to come, but they were cautious. In these meetings and in other random encounters, people were curious about the United States. On the street, vendors not only sold Russian nesting dolls with the rushed visages of Boris Yeltsin, who had defied the tanks of the coup, and of Gorbachev but also stacking dolls of U.S. presidents, including one set that had George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. I was asked by numbers of people, including the writers, if I could get them copies of the U.S. Constitution and the Federalist papers. The Berlin Wall had fallen and times were changing, but no one knew how that change would settle out in the Soviet Union.

Stall of street vendor selling Russian Matryoshika dolls, including stacking dolls of Boris Yeltsin and Mikhail Gorbachev and also U.S. Presidents.

I remember one meeting in Moscow with members of a women’s theater cooperative—actresses, director, costume designer, and playwright. Before the member who spoke English arrived, we were left to communicate with each other by hand gestures and a few common words. Finally, the sturdy, broad-chested Russian writer who spoke English entered. I asked her what she did during the coup attempt. She stood, spread out her arms and declared triumphantly, “I stopped the tanks with my breasts!” This image has stayed with me, along with her words and the determined words of her fellow thespians and writers in that apartment, women demanding as their due freedoms they hadn’t yet experienced.

Joanne and members of Russian women’s theater cooperative in Moscow apartment, 1991.

Not only in the USSR but elsewhere, old dictatorships were crumbling, in Africa and Latin America. PEN was a refuge writers often looked to before democracy and political liberalization took hold in their countries. In September 1991 at the Vienna Congress, a month after the coup attempt, the Soviet Russian Center applied and received approval to change its name to Russian PEN. The debate within PEN was when to recognize a center. It was necessary to have enough qualified writers committed to the freedoms embedded in the PEN Charter and to have an environment in which the writers could feasibly operate, at least to some extent.

As the USSR broke apart, writers gathered and petitioned for PEN centers, sometimes before the regions claimed full independence. A PEN Center of the Soviet Asian Republics, including the literatures of the five separate regions of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tadzhikistan had been recognized at the Paris gathering in April 1991, but by PEN’s September 1993 Congress in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, writers from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan all proposed separate centers of PEN. Russian PEN supported the disbanding of the Soviet Central Asian Center because it had not functioned, because the Soviet Union no longer existed, and because the President of the center had made public statements racially slandering others, and he refused to withdraw these. It is rare for PEN to challenge a member and withdraw membership, but the use of PEN to advocate racially intolerant and provocative positions is a rationale; PEN did so as well with certain members in the Balkans during the war there.

The Kazakhstan Center was accepted as a PEN Center at the Congress in 1993; the vote on Kyrgyzstan’s proposal was delayed until more information about the writers could be gathered, and it was agreed the situation in Turkmenistan, still governed by a dictatorship, remained too problematic for a PEN center to exist.

PEN often mirrored the global landscape. In the early 1990’s PEN added centers in Albania, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Bosnia, and an ex-Yugoslav Center for writers in exile from the former Yugoslavia. Also new centers formed in the Congo, Mozambique, Malawi, Kenya, Guadalajara, Palestine as well as a Chinese Writers Abroad Center, an Iranian Writers in Exile Center, and an African Writers Abroad Center. The abroad and exile centers included members living outside the regions. At the Barcelona Congress in 1992 the acceptance of a Palestinian PEN Center was unanimous, including by the Israeli PEN and represented a hope that writers in the region would engage with each other. Also a Welsh Center and an Esperanto Center were added in the early 1990s.

PEN was growing quickly. It doubled in size in ten years, from 50 centers to more than 100 centers in 1992. Its finances, however, did not grow at the same rate, and the governing structure was essentially the same—an elected President, International Secretary and Treasurer who comprised the executive of International PEN. Staff also had hardly grown. Elizabeth Paterson, the Administrative Secretary had to manage the increasing workload with the addition of Jane Spender as her assistant. The Writers in Prison Committee, which operated with a separate budget, in a separate room, consisted of only two researchers—Sara Whyatt ,coordinator, and Mandy Garner and later a few interns.

During Michael Scammell’s years as Chair of WiPC and later during Thomas von Vegesack’s term, the Writers in Prison Committee focused its work on behalf of imprisoned and threatened writers, and on occasion tension arose between the Secretariat’s goal of promoting literature and comity among writers and the WiPC’s goal of protecting writers in oppressive regimes. The ultimate organizational decisions fell to the Secretariat between Congresses and in consultation with the Assembly of Delegates which met twice a year at Congress. Because of budgetary restraints and the growing size and expense of the Congresses, PEN reduced its Congresses to only once a year, beginning in 1994.

PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee Report, September 1991 presented to the November 1991 PEN Congress in Vienna. PEN’s complete Case List for this period included 143 pages of cases of writers and journalists around the world reported kidnapped, “disappeared,” executed, having died in custody, imprisoned, banned, under house or town arrest, deported or awaiting trial.

Controversy around the narrow base of decision-making came to a confrontation over the April 1993 Congress in Dubrovnik, Croatia. The Balkan War was raging. At the Rio Congress in December 1992 the American delegate questioned the wisdom of holding the Congress in a war zone not only for reasons of safety but also for the appearance and possible “political misuse” of PEN in one corridor of the riven community and the restrictions on talking freely with the press. Others felt holding the Congress, most of which would be on a ship that would sail from Venice to Dubrovnik, would have a symbolic message of peace and also commemorate PEN’s Dubrovnik Congress 60 years earlier in 1933 when PEN exlcuded official writers of Nazi Germany from the organization. The host center assured that all centers from the region would attend. When delegates asked that the Dubrovnik Congress either be cancelled or postponed, they were told the decision had been made two years before, and there was no need for the Assembly to take a vote. Later as the war escalated, a mail vote was taken and the majority who responded voted for postponement, but the Croatian center, which had put in considerable work, wanted to hold the Congress, and so the plans went ahead.

On April 12, a week before the PEN gathering, the Army of the Republic of Srpska launched an attack on the town of Srebrenica in Bosnia, 200 miles from Dubrovnik. Many PEN Centers chose not to send delegates, including American and German PEN. The Writers in Prison Committee in the person of Thomas also chose not to attend nor did many of the WiPC members. Because there was not a quorum, the gathering was declared not an official congress, but a meeting.

I did not attend either the Dubrovnik meeting nor the earlier Rio Congress. Before the November 1992 Congress in Rio, Thomas and International Secretary Alexander Blokh without consulting with each other asked if I would take over the Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee when Thomas finished his term in September 1993. The fact that these two individuals both came to me made me consider carefully, but I was among the younger generation of PEN members who was urging more democratic procedures for PEN. I didn’t think the Chair should be an appointive office but should have the input of the PEN members, but in 1992, PEN had no such systems in place. Alex told me that he would canvas people at the Rio Congress to see if they agreed and get back to me. I don’t know what process was used nor how widely he asked, but he and Thomas returned in agreement and urged me to accept. I agreed, though I said that when my term was up, I wanted to assure we had set in place a more democratic system for nominations and election of the WIPC Chair. And so we did and have ever since.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 9: The Fraught Roads of Literature

PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move: West to East

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I have attended 32 International PEN Congresses as president of a PEN Center, often as a delegate, as Chair of the International Writers in Prison Committee, as International Secretary and now as Vice President. The number surprises me when I count. The Congresses have been held on every continent except Antarctica. Many were grand affairs where heads of State such as Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, Angela Merkel in Germany, Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal greeted PEN members. Some were modest as the improvised Congress in London in 2001 when PEN had to postpone the Congress planned in Macedonia because of war in the Balkans. PEN held its Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia the following year. At these Congresses writers from PEN centers all over the globe attended. Today PEN International has centers in over 100 countries.

Among the more memorable and grand was the 54th PEN Congress in Canada, held in September 1989 when PEN still held two Congresses a year. The Canadian Congress, staged in both Toronto and Montreal by the two Canadian PEN centers, moved delegates and participants between cities on a train. The theme—The Writer: Freedom and Power—signaled hope at a time when freedom was expanding in the world with writers wielding the megaphone.

54th PEN Congress in Canada, 1989. Front row: WiPC chair Thomas von Vegesack, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman and PEN USA West Executive Director Richard Bray. Back row: Digby Diehl (right) and other delegates.

The literary programs included luminary writers from over 25 countries, including Margaret Atwood (Canada), Chinua Achebe (Nigeria), Anita Desai (India), Tadeusz Konwicki ( Poland), Claribel Alegria (El Salvador), Margaret Drabble (England), Michael Ignatieff (Canada), Ama Ata Aidoo (Ghana), Derek Walcott (St. Lucia), John Ralston Saul (Canada), Duo Duo (China), Harold Pinter (England), Tatyana Tolstaya (USSR), Alice Munro (Canada), Wendy Law-Yone (Burma), Larry McMurtry (USA), Emily Nasrallah (Lebanon), Yehuda Amichai (Israel), Maxine Hong-Kingston (USA), Michael Ondaatje (Canada), Nancy Morejn (Cuba), Jelila Hafsia (Tunisia), Miriam Tlali (South /Africa), and dozens more, and other writers listed in absentia such as Vaclav Havel (Czechoslovakia) and writers from Iran, Turkey, Hungary, South Africa, Morocco and Vietnam. PEN members and delegates attended from at least 57 PEN centers around the world.

The new PEN International President Rene Tavernier, a poet who had been active in the French resistance during World War II, hailed the importance of the writer’s role in upholding freedom of expression around the globe and in confronting central power which restricted individual voices. PEN’s and the writer’s only weapon was the word, he said, and the word must be used in service of “creative intelligence, human rights, lucidity and hope.” Though the twentieth century had seen “the growth of new and atrocious ideologies with their police forces and concentration camps, they could not change the spirit of man, which is what PEN defends,” he said. PEN’s concern was literature and ideas and conversations among writers, who may not always agree.

A goal of the Congress was to expand dialogues among people, especially in Muslim communities in the wake of the fatwa and to expand PEN’s reach into Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. Today PEN centers in those areas have grown exponentially with 33 centers in Africa and the Middle East and 19 centers in Latin America, though participation from these centers in global forums still remains challenging.

Another outcome of the Congress was the formation of the PEN Women’s Network, a precursor to the Women’s Committee established as a standing committee of PEN two years later at the 1991 Vienna Congress. The Canadian Congress organizers had balanced literary panels and discussions among men and women, a response to the growing voice of women in PEN and to the 1986 New York Congress where men dominated the forums. Some opposed a Women’s Committee, including English PEN which voiced concern that it would fragment and divide members when the goal of PEN was to bring people together. English PEN already operated under a guideline that balanced men and women in leadership. PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer wrote that she had “more pressing obligations here, at home in South Africa, towards the needs of both women and men who are writers under our difficult and demanding position, beset by censorship, harassment, and lack of educational opportunities common to both sexes.” But she added that she hoped if a committee did form, it would be in touch with all South African writers.

PEN USA West presented a resolution on South Africa at the Congress, protesting the arrest and treatment of a number of writers, including our honorary member. The resolution passed unanimously in the Assembly of Delegates.

My fellow delegate and I also joined American PEN as well as Canadian PEN, Hong Kong and Taipei PEN in a resolution protesting the “slaughter of Chinese citizens peacefully assembled in and around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square” three months before and the arrest of writers, including Liu Xiaobo and over 20 others. It was feared some of the China PEN members might be under threat. Neither the China Center nor the Shanghai Center were present at the Canadian Congress, but they had been in touch with PEN International. In an official communication the Shanghai Center protested that China was being slandered abroad. Representatives from the two Chinese Centers had demanded an apology from PEN International because poet Bei Dao had been allowed to address the Maastricht Congress (see PEN Journey 3) and they continued to argue that PEN’s main case Wei Jingsheng was not a writer. An apology was not offered, and the resolution protesting the killings and arrests after Tiananmen Square passed with one abstention. Delegates from the China Center and Shanghai Center didn’t return to a PEN Congress for the next two decades, but in the intervening years, individual centers and members such as Japanese writers stayed in touch. In 2001 an Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) formed and gave a place for Chinese writers inside and outside of China to communicate with discussion and debate on freedom of expression and democracy. PEN currently has more than half a dozen centers of Chinese writers, including the China, Shanghai, ICPC, Taipei, Hong Kong, Tibet, Uyghur, and Chinese Writers Abroad centers.

The challenge for PEN has always been how best to use its formal resolutions, written in the language of the United Nations. These are passed then directed to the respective governments, to United Nations forums and to embassies and officials in the countries where PEN has centers and to the media. The effort begins at the PEN International office and then fans out through the centers. The impact of the resolutions vary according to country and to the direct advocacy efforts. However, the climate for such resolutions has altered over the years, and it is an ongoing question what is the most impactful method for effecting change.

At the Canadian Congress the situation in Myanmar/Burma was also highlighted. Our center, along with Austrian, Australian (Perth), and Canadian centers presented a resolution protesting the slaughter of Burmese citizens and the wholesale arrests and imprisonment without trial of citizens, including writers, after the imposition of martial law. I met one of these writers—Ma Thida—in London years later after PEN had advocated aggressively for her release. She’d spent almost six years in prison. A physician, writer and editor and an assistant for Aung San Suu Kyi, she remained committed to freedom for her country. It took another 15 years before the Myanmar government eased restrictions and a civilian government took over. When the political situation in Burma/Myanmar began to open, Ma Thida, Nay Phone Latt and other writers, many of whom had been in prison, formed a PEN Myanmar Center which joined PEN’s Assembly at the 2013 Congress in Reykjavik, Iceland. Ma Thida was its first president, and she now serves on the International Board of PEN.

Ma Thida and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the PEN Congress in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan in October 2014

For me, the outward facing Canadian Congress mirrored my own preparation for moving with my family to London three months later in January 1990. It was a fortuitous time to live in Europe as Eastern Europe was opening to the West. Six weeks after the PEN Congress, East Germany announced that its citizens were free to cross into the West, and the Berlin Wall began to crumble figuratively and literally as citizens used hammers and picks to knock down the looming concrete structure. In fall 1990, I took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to East Berlin, and we too climbed up on ladders with metal rods and knocked down the wall, chunks of which we still have.

Joanne and sons Elliot and Nate at the Berlin Wall, Fall 1990

At the Canadian Congress, PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair Thomas von Vegesack asked that a sub-committee be formed to assist in fundraising. Eight centers—Australian (Perth), Canadian, Swedish, Norwegian, West German, English, American and USA West agreed to help. Because I was moving to London where PEN International was headquartered, Thomas asked if I would head the effort. I told him I wasn’t able to do so but agreed to take on the interim position and help him find a chair and then agreed to take on the task of getting PEN International charitable tax status. I assumed the latter mission would be fairly straightforward, a matter of finding the right law firm to assist. Little did I know the complications of British charitable tax law. Eventually Graeme Gibson, president of PEN Canada, novelist and partner of Margaret Atwood, agreed to head the development effort.

After I arrived in London, I found a law firm. Charitable tax status would relieve PEN of tax bills it found hard to pay and also help with fundraising, but so far PEN had not been able to secure the charitable status. Thomas and I, along with the International Secretary Alexander Blokh, Treasurer Bill Barazetti and Administrative Secretary Elizabeth Paterson met frequently at the PEN International offices at the top of four (or was it five?) very steep flights of stairs in the Charterhouse Buildings where we worked on what turned out to be a two-year project that included the establishment of the International PEN Foundation. The Foundation was allowed to raise tax-exempt funds for the “charitable” work of PEN which could not include perceived “political” work, but only the “educational” aspects.

It took a young American who didn’t know it was impossible to do what we have not been able to do, Antonia Fraser said to me as she joined the first board of the International PEN Foundation in 1992. In a way she was right for I had no idea the complexity of British tax law, quite different than America’s. I wasn’t prepared for the sets and sets of documents and negotiations, the time required to set up a separate organization; on the other hand, the effort opened up the workings of PEN International to me and introduced me to friends I’ve maintained over the decades who also worked on the project. On the Foundation board with me were a majority of British citizens (and PEN members), including Antonia Fraser, Margaret Drabble, Buchi Emecheta, Andre Schiffrin, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson and later Ronald Harwood as well as a few other international members, PEN’s International Secretary, Treasurer and the new PEN President Gyorgy Konrad.

Harold Pinter’s play Moonlight premiered as the first fundraising event of the International PEN Foundation on October 12, 1993 at the Almeida Theater. Dramatically, the lights of the theater burnt out just before the performance, and the play was performed by candlelight.

First International PEN and PEN Foundation brochure.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 5: PEN in London, Early 1990’s

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

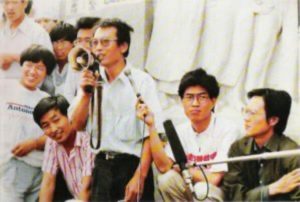

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East