Posts Tagged ‘Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’

PEN Journey 9: The Fraught Roads of Literature

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

Twelve-foot puppets danced outside the dining room’s second floor windows at our hotel, billed as the “oldest hotel in the world,” set on the central plaza of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, the venue for PEN International’s 60th Congress.

Sara Whyatt, coordinator of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, and I hurried to finish breakfast and our agenda before we joined the crowds outside at the historic Festival of St. James. That evening International PEN’s 60th Congress would convene. Hosted by Galician PEN, the Congress had as its theme Roads of Literature, which seemed appropriate as pilgrims from around the world also gathered on the Obradoiro Plaza in front of the ancient Cathedral, the destination for their Camino.

Parador Hotel, Santiago de Compostela St. James Festival, Obradoiro Plaza, Santiago de Compostela

At this Congress the presidency of PEN was changing hands as was the chairmanship of the Writers in Prison Committee, which I was taking over from Thomas von Vegesack. Ronald Harwood, the British playwright, was assuming the PEN presidency from Hungarian novelist and essayist György Konrád, who had been a philosophical president, often running the Assembly meetings like a stream of consciousness event where the agenda was a guide but not necessarily a governing map. Ronnie ran the final meeting like a director and dramatist, determined to get the gathering from here to there with a path and deadline. Both smart, experienced writers, committed to PEN’s principles, they had very different styles. Known only to a few of the delegates a surprise visitor was also arriving mid-Congress.

The 60th Congress in September 1993 was a watershed of sorts. It was the first since the controversial Dubrovnik gathering six months before which had split PEN’s membership (see PEN Journey 8) because of the war in the Balkans.

Konrád’s opening speech to the Assembly explained that PEN’s leadership had gone ahead with the congress over the many objections from PEN centers because the venue had been approved earlier by the Assembly and the host center had been unwilling to postpone. He acknowledged the widespread criticism and also the concern that some individuals who fomented the Balkan wars and participated in alleged war crimes were writers who had been members of PEN. He said, “That these men of war also include men of letters, indeed that these latter are well represented, painfully confronts our professional community with the notion of our responsibility for the power of the Word. Nationalist rhetoric led to mass graves here, and there. Mutual killings would not have been on such a scale in the absence of words that called on others to fight or that justified the war.”

György Konrád, PEN International President 1990-1993, Credit: Gezett/ullstein bild, via Getty Images

Konrád’s address at the opening session went a way in bringing the delegates together. “What we can do is to try and ensure the survival of the spirit of dialogue between the writers of the communities that now confront each other….International PEN stands for universalism and individualism, an insistence on a conversation between literatures that rises above differences of race, nation, creed or class, for that lack of prejudice which allows writers to read writers without identifying them with a community…

“Ours is an optimistic hypothesis: we believe that we can understand each other and that we can come to an understanding in many respects. The existence of communication between nations, and the operation of International PEN confirm this hypothesis…PEN defends the freedom of writers all over the world, that is its essence.”

Ronald Harwood added in his acceptance for the presidency: “The world seems to be fragmenting; PEN must never fragment. We have to do what we can do for our fellow-writers and for literature as a united body; otherwise we perish. And our differences are our strength: our different languages, cultures and literatures are our strength. Nothing gives me more pride than to be part of this organization when I come to a Congress and see the diversity of human beings here and know that we all have at least one thing in common. We write…We are not the United Nations…We cannot solve the world’s problems…Each time we go beyond our remit, which is literature and language and the freedom of expression of writers, we diminish our integrity and damage our credibility…We don’t’ represent governments; we represent ourselves and our Centres…We are here to serve writers and writing and literature, and that is enough…And let us remember and take pleasure in this: that when the words International PEN are uttered they become synonymous with the freedom from fear.”

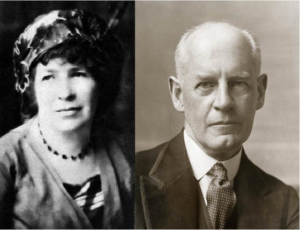

Ronald Harwood, PEN International President 1993-1997. Credit BAFTA

PEN’s work to defend writers and protect space free from fear fell in large part to the Writers in Prison Committee, the largest of PEN’s standing committees with over half the PEN centers operating their own WiP Committees. Members elected the writers who were in prison for their writing as honorary members of their centers, corresponded with them and their families, advocated on their behalf with their own governments and with the governments where the writers lived. PEN’s London office provided the research, selected the cases, planned campaigns and worked with international bodies. The means and methods have modified over the years as the internet and social media have developed, but the focus has remained on the individual writer whose case is pursued until it is resolved. With consultative status at the United Nations, International PEN and its Writers in Prison Committee work through the Human Rights Commission and UNESCO and with other international institutions lobbying on behalf of writers.

At the time of the 60th Congress focus of WiPC’s work included China, Turkey, Algeria, Burma, Syria and Nigeria. In Turkey that summer an arson attack at an arts festival in Sivas had killed at least 37 people, seven writers and poets. One of the writers at the festival Aziz Nesin was translating Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses into Turkish and had started to serialize the book in a newspaper. Nesin’s presence at the festival was said to inflame the local crowds. Though Nesin survived, it was reported he was beaten by the firefighters who saved him, and a subsequent investigation held the Turkish state responsible. China continued to have more WiPC cases than any country except Turkey. The threat of death for writers had intensified in Algeria where Islamic extremists had assassinated six writers, including the novelist and journalist Tahar Djaout. In Nigeria the brief imprisonment and possible sedition charges against writer Ken Saro Wiwa, President of the Nigerian Association of Authors, founding member of Nigerian PEN and leader of the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People was highlighted after his passport was confiscated. A few years later his situation would inspire a global mobilization by PEN and human rights groups after Saro Wiwa was condemned to death by Nigeria’s de facto President Sani Abacha.

The focus of the 60th Congress remained on the Balkans and on growing religious extremism. PEN’s surprise guest appeared at the Assembly in the middle of the Peace Committee report on the Balkans. That morning delegates had entered through a metal detector and security check, the first and only time in my years at PEN. The day before, the guest was to have slipped into the hotel secretly because of security concerns, but the plaza outside was filled with people who had come to see the arrival not of Salman Rushdie but of singer Julio Iglesias who arrived at the same time. Rushdie was quickly whisked inside. That evening a small group gathered for dinner with Rushdie in a private dining room at the hotel. I remember sitting beside Salman and sharing a dessert with him but have no notes from the dinner and remember only a discussion of PEN’s further campaign on his behalf. At the time the fatwa weighed heavily. Translators and publishers of Rushdie had been killed and attacked.

The next morning Rushdie arrived in the hall during the Peace Committee’s report which took a break for Rushdie’s address. The Assembly passed a resolution again condemning the fatwa and urging Iran to rescind it and urging all PEN Centers to continue lobbying their governments on Rushdie’s behalf and to put the case on the agenda of the International Court of Justice and other multilateral fora.

International PEN 60th Congress Assembly of Delegates in Santiago de Compostella 1993. Left to right: György Konrád, Salman Rushdie, Ronald Harwood

To the Assembly Rushdie noted: “…in the Muslim world, in the Arab world when journalists and academics and other visitors ask writers, intellectuals, and other dissident figures in those countries what they think, they repeatedly say: ‘The reason you must defend Rushdie is that by doing so you defend us also.’ For example, Iranian dissident intellectuals, 167 of whom recently signed a very passionate declaration in support of me and of the principles involved in this case, say that the real target of the Khomeini Fatwa and of Iranian state terrorism is not Rushdie, it is them.’ After all I have protection; they don’t. And what the terror campaign means is ‘If we can do this to Rushdie, think how much we can do to you.’”

He said, “There is something I wanted to say about the issue of fear. I do think that a lot of people who mean well and wish to combat this kind of attack are silenced by fear, and think that by remaining silent, somehow things will get better…But the one thing that I’ve learned is that silence is always the biggest mistake, always no matter how great the temptation to silence might be, for a very simple reason. If you are silent, you allow your enemy to speak, and therefore you allow him to set the terms of the debate…I think one of the reasons I’m here is that all of you, and thousands of people around the world have not remained silent.”

Rushdie thanked PEN for its work on his behalf. When asked how this situation affected his writing, he said he’d actually become more optimistic. “I was determined to construct a happy ending and discovered it is very difficult. Happy endings in literature as in life are very difficult to arrange…[but] the answer is that it’s made my writing much more cheerful.”

Rushdie stayed after his address and participated in the discussion on the Balkans. Miloš Mikeln, chair of the Peace Committee, reported that besides help provided to writer refugees and those staying in Sarajevo, the Peace Committee was closely following and analyzing the situation in the war regions, focusing on writers’ involvement in instigating chauvinistic hatred and war propaganda. The most drastic case was that of the Serbian poet from Bosnia, Mr. Radovan Karadzic, who was now the President of the self-proclaimed Serbian Republic of Bosnia. The Peace Committee report noted that he’d used his literary talent and his reputation as a writer to foster ethnic and religious hatred and to promote genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina. “As writers who deeply believe in freedom of expression we cannot remain silent in the face of such an abuse of the freedom,” Mikeln said. “We find it incumbent upon us to condemn Radovan Karadzic for his violation of all the values that we and International PEN stand for.”

After lengthy debate on whether to name names in resolutions, this condemnation was accepted and taken as a statement of the Writers for Peace Committee. Personal condemnation is highly unusual for PEN, used most notably in the expulsion of Nazi writers in 1933. The debate further focused on the responsibility of PEN members, in particular Serbian PEN members and the Serbian center. It is also very unusual for the PEN Assembly to publicly call out a center. The resolution noted, “Writers in Serbia actively supported chauvinistic propaganda, misusing their influence as writers and thus instigating hatred, destruction and war. These actions including public statements by ___ and _____clearly run against the principles of International PEN. The 60th World Congress…condemns such a blatant abuse of our profession. We expect the Serbian PEN to take a stand against this breach of writers’ ethics as we would expect of any Center confronted by a similar situation.” In this instance the names were included in the original resolution but after debate were left out of the resolution passed by the Assembly.

The Bosnian delegate made a passionate plea protesting what was happening in Bosnia and the characterization of the situation as “civil war” by others. Rushdie said that the delegate from Bosnia was justified and should be heard. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the situation, there was no question that the crimes committed against Bosnia had been the greatest and Sarajevo the most tragic case, Rushdie said, and he hoped the delegate was wrong when he said people outside did not care and did not want to know. The destruction of Sarajevo would haunt Europe for generations, and he added that the people who had wanted to maintain a unified society had been sacrificed, and it was hard not to believe that it was because they were Muslims. Suppose the Serbs had been Muslims. The Bosnian culture was the culture of Europe.

The Assembly of Delegates approved the Peace Committee’s resolution with names removed and also endorsed a recommendation by Russian PEN that was to be annexed to the resolution. That statement declared that PEN “expresses its firm conviction that the duty of writers, and particularly of the writers of those ethnic groups and countries which are directly involved in the armed conflicts is not to espouse national interests but, in the cause of the unity of the world, promote negotiation and compromise so as to obtain the solution of all conflicts.”

PEN Congresses are full of speeches and resolutions, words offered in a world buffeted by much harder power, but PEN members have faith that words matter and can have power for good or ill, that there is a difference between words that aim for truth and words that are used for propaganda. At that time and in times before and since, words have inspired peace but also inflamed towards war. PEN remains a place where words and actions come together in campaigns to preserve the freedom of writers to use their words.

At the 60th PEN Congress in the grand ballroom of the oldest hotel in the world a new Bosnian Center whose members were Serb, Croat and Bosnian was unanimously welcomed as was an ex-Yugoslav Center for writers who no longer lived in the region.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 10: WiPC: Beware of Principles

PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

In fall, 1991 I went to Moscow just months after the August coup attempt in which hardline Communists sought to take control from President Mikhail Gorbachev. I hopped onto the visa of my husband who was traveling to Russia as a Visiting Scholar at the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London. I went as a writer, interested in meeting other writers. I contacted fellow PEN member and Russian translator Michael Scammell, who had previously chaired International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). Michael gave me a list of writers to contact in Moscow.

Statues toppled of Lenin and Stalin and others in park after failed coup attempt in Moscow, 1991.

My husband and I stayed in what I was told was one of the government hotels where guests were hosted but also watched. We were watched too, I’m fairly certain, though there was little for anyone to see with me. I was cautious as I made contact with the writers lest my reaching out compromise them. Only a few years before, PEN’s case list had included many dissident Soviet writers in prison. Michael and later WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack and PEN’s WiPC committees around the world had advocated for the release of dissident Soviet writers, many of whom were imprisoned in the gulags. PEN had also covertly sent aid to them and their families through the channels of the PEN Emergency Fund.

I no longer remember if I called or faxed the writers in advance. (Fall, 1991 was before an active internet.) I likely made contact when I arrived. The writers welcomed me. We met in simple apartments with old holiday cards on the mantles as decorations, a paper mobile hanging from the light fixture over one dining room table I recall, strips of newspaper stacked by the toilets in lieu of tissue. The economy was spare for these writers. They hoped for change and for freedoms to come, but they were cautious. In these meetings and in other random encounters, people were curious about the United States. On the street, vendors not only sold Russian nesting dolls with the rushed visages of Boris Yeltsin, who had defied the tanks of the coup, and of Gorbachev but also stacking dolls of U.S. presidents, including one set that had George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. I was asked by numbers of people, including the writers, if I could get them copies of the U.S. Constitution and the Federalist papers. The Berlin Wall had fallen and times were changing, but no one knew how that change would settle out in the Soviet Union.

Stall of street vendor selling Russian Matryoshika dolls, including stacking dolls of Boris Yeltsin and Mikhail Gorbachev and also U.S. Presidents.

I remember one meeting in Moscow with members of a women’s theater cooperative—actresses, director, costume designer, and playwright. Before the member who spoke English arrived, we were left to communicate with each other by hand gestures and a few common words. Finally, the sturdy, broad-chested Russian writer who spoke English entered. I asked her what she did during the coup attempt. She stood, spread out her arms and declared triumphantly, “I stopped the tanks with my breasts!” This image has stayed with me, along with her words and the determined words of her fellow thespians and writers in that apartment, women demanding as their due freedoms they hadn’t yet experienced.

Joanne and members of Russian women’s theater cooperative in Moscow apartment, 1991.

Not only in the USSR but elsewhere, old dictatorships were crumbling, in Africa and Latin America. PEN was a refuge writers often looked to before democracy and political liberalization took hold in their countries. In September 1991 at the Vienna Congress, a month after the coup attempt, the Soviet Russian Center applied and received approval to change its name to Russian PEN. The debate within PEN was when to recognize a center. It was necessary to have enough qualified writers committed to the freedoms embedded in the PEN Charter and to have an environment in which the writers could feasibly operate, at least to some extent.

As the USSR broke apart, writers gathered and petitioned for PEN centers, sometimes before the regions claimed full independence. A PEN Center of the Soviet Asian Republics, including the literatures of the five separate regions of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tadzhikistan had been recognized at the Paris gathering in April 1991, but by PEN’s September 1993 Congress in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, writers from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan all proposed separate centers of PEN. Russian PEN supported the disbanding of the Soviet Central Asian Center because it had not functioned, because the Soviet Union no longer existed, and because the President of the center had made public statements racially slandering others, and he refused to withdraw these. It is rare for PEN to challenge a member and withdraw membership, but the use of PEN to advocate racially intolerant and provocative positions is a rationale; PEN did so as well with certain members in the Balkans during the war there.

The Kazakhstan Center was accepted as a PEN Center at the Congress in 1993; the vote on Kyrgyzstan’s proposal was delayed until more information about the writers could be gathered, and it was agreed the situation in Turkmenistan, still governed by a dictatorship, remained too problematic for a PEN center to exist.

PEN often mirrored the global landscape. In the early 1990’s PEN added centers in Albania, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Bosnia, and an ex-Yugoslav Center for writers in exile from the former Yugoslavia. Also new centers formed in the Congo, Mozambique, Malawi, Kenya, Guadalajara, Palestine as well as a Chinese Writers Abroad Center, an Iranian Writers in Exile Center, and an African Writers Abroad Center. The abroad and exile centers included members living outside the regions. At the Barcelona Congress in 1992 the acceptance of a Palestinian PEN Center was unanimous, including by the Israeli PEN and represented a hope that writers in the region would engage with each other. Also a Welsh Center and an Esperanto Center were added in the early 1990s.

PEN was growing quickly. It doubled in size in ten years, from 50 centers to more than 100 centers in 1992. Its finances, however, did not grow at the same rate, and the governing structure was essentially the same—an elected President, International Secretary and Treasurer who comprised the executive of International PEN. Staff also had hardly grown. Elizabeth Paterson, the Administrative Secretary had to manage the increasing workload with the addition of Jane Spender as her assistant. The Writers in Prison Committee, which operated with a separate budget, in a separate room, consisted of only two researchers—Sara Whyatt ,coordinator, and Mandy Garner and later a few interns.

During Michael Scammell’s years as Chair of WiPC and later during Thomas von Vegesack’s term, the Writers in Prison Committee focused its work on behalf of imprisoned and threatened writers, and on occasion tension arose between the Secretariat’s goal of promoting literature and comity among writers and the WiPC’s goal of protecting writers in oppressive regimes. The ultimate organizational decisions fell to the Secretariat between Congresses and in consultation with the Assembly of Delegates which met twice a year at Congress. Because of budgetary restraints and the growing size and expense of the Congresses, PEN reduced its Congresses to only once a year, beginning in 1994.

PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee Report, September 1991 presented to the November 1991 PEN Congress in Vienna. PEN’s complete Case List for this period included 143 pages of cases of writers and journalists around the world reported kidnapped, “disappeared,” executed, having died in custody, imprisoned, banned, under house or town arrest, deported or awaiting trial.

Controversy around the narrow base of decision-making came to a confrontation over the April 1993 Congress in Dubrovnik, Croatia. The Balkan War was raging. At the Rio Congress in December 1992 the American delegate questioned the wisdom of holding the Congress in a war zone not only for reasons of safety but also for the appearance and possible “political misuse” of PEN in one corridor of the riven community and the restrictions on talking freely with the press. Others felt holding the Congress, most of which would be on a ship that would sail from Venice to Dubrovnik, would have a symbolic message of peace and also commemorate PEN’s Dubrovnik Congress 60 years earlier in 1933 when PEN exlcuded official writers of Nazi Germany from the organization. The host center assured that all centers from the region would attend. When delegates asked that the Dubrovnik Congress either be cancelled or postponed, they were told the decision had been made two years before, and there was no need for the Assembly to take a vote. Later as the war escalated, a mail vote was taken and the majority who responded voted for postponement, but the Croatian center, which had put in considerable work, wanted to hold the Congress, and so the plans went ahead.

On April 12, a week before the PEN gathering, the Army of the Republic of Srpska launched an attack on the town of Srebrenica in Bosnia, 200 miles from Dubrovnik. Many PEN Centers chose not to send delegates, including American and German PEN. The Writers in Prison Committee in the person of Thomas also chose not to attend nor did many of the WiPC members. Because there was not a quorum, the gathering was declared not an official congress, but a meeting.

I did not attend either the Dubrovnik meeting nor the earlier Rio Congress. Before the November 1992 Congress in Rio, Thomas and International Secretary Alexander Blokh without consulting with each other asked if I would take over the Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee when Thomas finished his term in September 1993. The fact that these two individuals both came to me made me consider carefully, but I was among the younger generation of PEN members who was urging more democratic procedures for PEN. I didn’t think the Chair should be an appointive office but should have the input of the PEN members, but in 1992, PEN had no such systems in place. Alex told me that he would canvas people at the Rio Congress to see if they agreed and get back to me. I don’t know what process was used nor how widely he asked, but he and Thomas returned in agreement and urged me to accept. I agreed, though I said that when my term was up, I wanted to assure we had set in place a more democratic system for nominations and election of the WIPC Chair. And so we did and have ever since.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 9: The Fraught Roads of Literature

PEN Journey 7: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Iraq invaded Kuwait August 2, 1990. When I picked up my 10-year old son from camp in the U.S. that summer and told him what had happened, his first response was: What about Talal and Alec? These were two of his good friends at the American School in London—one was son of the Kuwaiti Ambassador; the other was from Iraq. He quickly understood the consequences. Fortunately, both of his friends had been out of their countries at the time, though I don’t recall Alec returning to the American School that fall. When the bombs dropped on Baghdad in January, the American School went into lockdown. The older students were issued identity cards. The security force around the school multiplied. When Talal came over to play that winter, he was accompanied by two imposing body guards who stayed outside.

Though the fighting in Iraq concluded by the end of February, security in London continued. By the end of March, the war in the Balkans had begun. Both wars brought to a close the honeymoon many felt after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For PEN, the outbreak of war in Iraq and in the Balkans led to the cancellation of the planned Delphi Congress and to the convening of conferences in Europe and a two-day gathering of PEN’s Assembly of Delegates and international committees in Paris in April 1991. Delegates from 39 PEN centers came together to conduct the business of PEN at the Société des Gens de Lettres de France which occupied the 18th-century neoclassical Hôtel de Massa on rue de Faubourg-Saint-Jacques in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. There were no literary sessions or social gatherings, or the usual simultaneous translation of proceedings. The business was conducted primarily in English with intermittent French, the two official languages of PEN. (Spanish was added a few years later as PEN’s third official language.)

The Gulf War, the ethnic conflict in the Balkans, the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square trials and the ongoing fatwa against Salman Rushdie predominated discussions in Paris and later in November at the 56th PEN Congress in Vienna. The Gulf War had resulted in increased numbers of writers imprisoned and killed in the Middle East and an increase in censorship. Resolutions condemning the detention and imprisonment of writers in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel and Turkey passed the Paris Assembly. Little information was available from Iraq. Another resolution in Paris sponsored by the two American centers expressed concern to the U.S. government and all U.N. member states over the restrictions placed on journalists during the war and urged a review of the ground rules for journalists in conflicts.

Turkey and China continued to hold the largest number of writers in prison, as has been the case for most of my 30-year involvement with PEN. At the time the Turkish government had announced an amnesty for approximately a third of the writers, and there was some hope they might release the additional 80, but new laws were also proposed that could be used against writers. In China where 87 cases were reported, the authorities had announced the end of investigations on the leaders of the June 1989 Democracy Movement. Most sentences were lighter than expected with credit given to human rights organizations like PEN who had kept up pressure.

However, this was not the case for Wang Juntao, a 32-year old academic and Deputy Editor of the Economics Weekly newspaper. In a letter to his lawyer published at the time in The South China Morning Post Wang Juntao explained why he had spoken as he had at the trial even though he knew his penalty would be more severe. “…Only by so doing can the dead rest in peace, since on the soil where they shed blood there are still some compatriots who take risks and speak out from a sense of justice in the most difficult circumstances…” His lawyers had been given just four days to prepare his defense. He was sentenced to 13 years in prison with four years subsequent deprivation of political rights for the crime of conspiracy to subvert the government and for carrying out counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement. His lawyers pressed him not to appeal so his wife had to do so and was given only three days. The appeal was rejected. [In 1994 Wang Juntao was one of the prisoners the U.S. demanded be released as a condition for trade talks. He was released from prison for medical reasons and now lives in exile in the United States where he has studied and received advanced degrees from Harvard University and a PhD from Columbia University. PEN was among the organizations which lobbied for this release.]

PEN International’s case sheet for Wang Juntao sent by fax and mail in 1990 to centers and members. In 1991 PEN International launched a Rapid Action Network to notify centers and to summarize the cases, actions and advocacy.

During this period PEN through its partnership with UNESCO convened writers in the Middle East and also writers in the Balkans to find common ground and to search out the pylons upon which bridges might be built and to monitor the situation for the writers in the regions. However, because of the Balkan War, it wasn’t possible to hold the meeting with the Yugoslav Centers in Bled as the Slovene Center had proposed. Instead PEN International President György Konrád hosted the gathering in Budapest and followed up with a meeting of South-Eastern European centers in Ohrid, hosted by Macedonian PEN though the Croatian Center wasn’t able to attend. The discussion included the desirability of recognizing the right of conscious objection in time of civil war and the possibility of solving the problem of minorities by allowing multiple citizenship.

Summary statement of the August, 1991 Conference on the Balkans with all centers from the former Yugoslavia attending except the Bosnian Center, which didn’t come into being until the following year.

In addition to convening dialogues among writers and lobbying on behalf of threatened writers during the Balkan conflicts, PEN also provided financial assistance. Boris Novak, the Slovene Chair of PEN’s Peace Committee and President of Slovene PEN took many precarious trips into war-torn Sarajevo during the almost four-year siege of the city. At one point he reported at least 52 writers and their families were trapped and could only leave if invited to an international peace conference. Slovene PEN planned to host such a conference and invite the writers and their families with the hope the U.N. Peacekeeping Force could provide protection for their exit. He urged other PEN centers to assist in finding residences and perhaps temporary teaching appointments or fellowships for these writers. He also delivered aid to trapped writers, aid gathered from other PEN Centers, donated to the Writers in Prison Committee Aid Fund and to PEN’s Emergency Fund run out of Amsterdam with Dutch PEN.

In an intersection of conflicts, the German and Finnish publishers of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses donated their proceeds from the book to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. By the Vienna Congress, Rushdie had lived 1000 days under death threat. PEN continued its defense of Rushdie and its protest against the accompanying violence of the fatwa. The Japanese translator of Satanic Verses had been killed, and the Italian translator badly beaten. (Two years later the Norwegian publisher was shot three times and left for dead.) The bounty had increased on Rushdie, and there was allegedly a hit squad deployed in Western Europe to assassinate him.

One of many letters sent by International PEN to support Salman Rushdie and to protest the ongoing fatwa.

My personal engagement and memories during this period focused on work with the Writers in Prison Committee and to a lesser extent with the formation of the Women’s Committee, which I supported but which others were driving, and with the establishment of the International PEN Foundation which would be able to receive tax exempt funds for many of these PEN activities. After a discussion of the Foundation’s framework at the Paris Conference, including assurances that the Foundation would not interfere or challenge PEN’s governance, I presented the formal proposal at the Vienna Congress where the Assembly of Delegates approved the establishment of an International PEN Foundation. The Foundation received official charitable status in March 1992 and operated for the next decade until British charitable tax laws changed and a separate foundation was no longer necessary.

Also at the Vienna Congress the Women’s Network, which had formed at the Canadian Congress in 1989, gained approval as a standing committee of International PEN with assurances that men and women were welcome and would work together. Meredith Tax, a chief strategist and one of the founders, explained the committee would involve more women in the work of PEN at all levels and address problems that particularly affected women writers in developing countries and would enable women to know each other’s work, much of which was not translated. “The Women’s Committee will be a force to strengthen, not weaken PEN,” she assured the Assembly.

The eventual governance of the Women’s Committee included PEN members from around the world and its chair rotated to different regions. Each of PEN’s standing committees had its own governing structure. The Women’s Committee was unique in its inclusiveness, which had its own challenges, but which foreshadowed a more inclusive governing structure for PEN International. Twenty-eight PEN centers signed up for the committee with 70 delegates and members, including men, attending the initial meeting.

L to R: Moniika van Paemel, (Belgium Dutch-speaking PEN) and Meredith Tax (American PEN) at Women’s Committee Planning meeting at Canadian Congress, 1989

At the time International PEN’s leadership was all male. In its 80-year history International PEN had never had a woman President and only one woman International Secretary and few women as Committee chairs though in many centers of PEN there was a growing balance of men and women members and leaders. In 2015 novelist and poet Jennifer Clement was elected the first woman President of International PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN Journey 5: PEN in London, Early 1990’s

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

I moved to London where International PEN is headquartered in January 1990 from Los Angeles. I came with my husband and my 9 and 11-year old sons who rarely wore long sleeves, let alone coats or jackets. A few weeks into our resettlement, London spun in its first major tornado of the decade with hail and winds whipping at hurricane force and cars and trees toppled and a few rooftops airborne. The weather was highly unusual for London. Our family, who was still in temporary housing, took the unwelcome weather as a welcome of sorts, signaling that we might just be in for an adventure. Did you see that roof flying…!

There were still complaints: only four television channels, movies strictly restricted by age and when you did get into a theater, you had assigned seats, milk that went bad in a day, delivered on the stoop in glass bottles, a refrigerator that barely held enough food for a day, appliances that came without plugs…And where was the sun?

Yet the magic of the city quickly affected us all. My youngest son discovered the best skateboarders lived in London, and London (and England) was full of history and castles, and my oldest son, who was soon moved ahead a grade in school because he was highly talented in math, met students from all over the world in his class at the American School, a few of whom talked and imagined in his orbit. He was put on the rugby team to help socialize and the following year on the wrestling team, where he eventually, as an adult and by then dual citizen, wrestled for Great Britain in the Olympics.

For me, finding home in London meant connecting with PEN, both International PEN and English PEN. Writers can be members of more than one PEN center, though can vote with only one center. I’d begun my PEN journey in Los Angeles at PEN Los Angeles Center (changed to PEN USA West). When my second book was published, I also joined PEN American Center, based in New York, and now in London. I joined English PEN, the oldest and the original PEN center since the organization was founded by British writers in 1921. International PEN and English PEN had separate offices, but the Administrative Secretary of International PEN and the General Secretary of English PEN were longtime friends and actually lived next door to each other in Fulham. The two organizations worked independently, yet closely together.

Early on I visited International PEN’s office, headquartered in Covent Garden on King Street in the Africa Centre. To get to the office at the front of the house, you had to go through the Africa Book Shop on the first floor. PEN had two rooms with several desks in the larger room with papers stacked everywhere. There was a filing cabinet and a photocopier and just enough space to squeeze between to get to the desk looking onto the street.

International PEN was kept functioning by the stalwart and efficient Elizabeth Paterson, who I don’t recall getting angry at anyone even as the work piled on and people around the world in PEN centers asked more and more of her, including the smart, demanding International Secretary Alexander Blokh. Alex flew in every month, usually from Paris, and displaced the Writers in Prison Committee’s small staff from the second office in order to conduct the business of PEN around the world. Alex was a former UNESCO official, and at that time UNESCO was one of International PEN’s major funders. When UNESCO was formed, according to Alex, it established organizations for the various arts, but when it came to literature, it recognized that PEN already existed, and so its outreach and funding funneled through PEN. Over the years PEN has grown more and more independent of UNESCO support.

Elizabeth, with her quiet intelligence and subtle humor, managed to keep International PEN running day to day while Alex developed the literary and cultural programs with the centers and the standing committees—the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, the Peace Committee, and the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). The WiPC tended to operate more autonomously with its elected chair Swedish publisher Thomas von Vegesack and before him Michael Scammell. When I arrived in London, there was also a petite gray-haired woman Kathleen von Simson, a volunteer who’d helped manage the Writers in Prison Committee work for years. PEN had recently hired a paid Coordinator Siobhan Dowd whose task was to professionalize the human rights work, and Siobhan hired researcher Mandy Garner. The two of them worked in the tiny second room. Siobhan eventually crossed the ocean to head up the Freedom to Write program at American PEN.

Fall 1990. Left to right: Elizabeth Paterson, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Per Wastberg (former PEN International President), Siobhan Dowd, Bill Barazetti

Also finding space on King Street was the Assistant Treasurer (and later International Treasurer) Bill Barazetti, who at that time was an unsung hero from World War II. It was later publicized that Bill had smuggled hundreds of Jewish children out of Prague with false identity papers he arranged. He was a wiry gray-haired former intelligence officer who’d also interrogated captured German pilots. Alex Blokh, whose pen name was Jean Blot, was an exiled Russian Jew, a lawyer and had also been active in the French Resistance during World War II, and Elizabeth had endured the bombings in London during the War. Though it was 1990 and the Berlin Wall and other barriers which had gone up after World War II were now falling, in the PEN office there was still a feeling of that post-War period, an abstemiousness and a fortitude of the dedicated amateur who knew what sacrifice was and endured no matter what. I couldn’t articulate the atmosphere at the time, but as an American born after the war, grown up in Texas and moving to London from Los Angeles, I felt the contrasts and the constraints. One small incident I remember was when a donation for a baby gift for the newly hired Sara Whyatt was being gathered. I offered £20 for the pot and was told by Elizabeth, “Oh, no, that amount would embarrass her.” The concept of anyone being embarrassed by a pooled £20 contribution silenced me. I put in £10 instead, still considered a large amount. Because I was new and an American, I tried to listen and learn, but I understood expectations and horizons were different.

A generation of my own joined the office in the persons of Jane Spender, a former editor, smart and literary who worked with Elizabeth and later Gilly Vincent, who took on the part time assignment to help with development work for the eventual International PEN Foundation. (see PEN Journey 4) Later Gilly became General Secretary of English PEN. I quickly learned to respect the differences; the American way was not the British way. I remember a fundraising event in which there must have been 20 major English writers featured and attending, and the ticket price was £25. The PEN Foundation netted perhaps £3000 that evening. In New York with that line up of writers, I am confident American PEN would have added at least one, if not two, zeros to the proceeds, but we were in London, and the event was not a glittery affair but more like a large family gathering of literary friends at someone’s home.

PEN International moved its offices in 1991 from Covent Garden to Charterhouse Buildings in Clerkenwell nearer the City of London. The new offices were on the top floor of a bonded warehouse, and I never met anyone who didn’t arrive breathless after climbing the steep four or five flights of stairs. There was no elevator, but there was an outside hoist where PEN could load supplies and mail out the window and drop or raise these to and from the ground, preferably not in the rain. Elizabeth set the door code as the beginning and ending years of World Wars I and II, an 8-digit code everyone could remember. The offices at Charterhouse Buildings were spacious compared to King Street—two large airy rooms, one for the Writers in Prison Committee and one for all the other work of PEN, a spacious entry room used as a meeting area and a smaller private office where the International Secretary could work or small meetings could be held. All the rooms were painted “magnolia”–a creamy white/yellow color. The full-time staff by then was, I think, three, along with four or five part-time staff and volunteers, including Jane Spender, Peter Day, editor of PEN International magazine, Bill Barazetti and later his daughter Kathy and occasional interns.

When Siobhan prepared to leave for the U.S., Thomas asked me to interview candidates with him for her replacement. Between interviews he explained to me his view of England in the constellation of Europe by a story of when a fog settled over the English Channel and the headline in a British paper announced: Continent Isolated. Later, when the Channel Tunnel finally connected Great Britain to France in 1994, I sent Thomas a note and a copy of the headline from a British paper: “You’ll be glad to know, Thomas: Continent No Longer Isolated, the headline read.

Thomas and I agreed on the best candidate, and PEN hired Sara Whyatt as the new Program Director of the Writers in Prison Committee. Sara came to PEN from Amnesty and set about further professionalizing WiPC’s research and advocacy work. Sara and Mandy split up the globe, with Mandy focusing on Latin America and Africa.

Across London in Chelsea, English PEN rented offices from the London Sketch Club on Dilke Street where it held weekly literary programs, a monthly formal dinner, an annual Writers Day Program honoring one writer—Arthur Miller, Graham Greene, and Larry McMurtry were three I recall—and a mid-Summer Party. The literary programs and dinners, held in the Sketchers studio and bar, featured writers such as Michael Ignatieff, Germaine Greer, Michael Holroyd, Jan Morris, Rachael Billington, A.L. Barker, Penelope Lively, Andrew Motion, A.S. Byatt, Margaret Foster, William Boyd, Margaret Drabble, Iris Murdoch, and frequently Antonia Fraser, Harold Pinter and Ronald Harwood, just to name a few.

When I moved to London and joined English PEN, the General Secretary Josephine Pullein-Thompson, a stalwart writer/member, managed the organization and kept it running with minimal staff and with active members. Author of young adult novels, Josephine wrote books about young girls and horses. When I close my eyes, I can hear her gruff voice and see her square face and think of horses. She was pragmatic and no-nonsense and what I think of as the epitome of a certain era of British resolve. She befriended me early, I think, because I was focused on a task—getting charitable status for PEN International which ultimately allowed English PEN to claim the same. It was Josephine years later who nominated me as a Vice President of International PEN.

Members of English PEN were passionate about PEN’s mission to protect and speak up on behalf of writers under threat in oppressive regimes. Among activities, members, including notable British writers such as Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, and Antonia Fraser, who were good friends, and Moris Farhi, a Turkish/British novelist with a great beard, great girth and great heart, who later succeed me as Writers in Prison Chair, and dozens of other English PEN members held vigils, often by candlelight. They protested outside embassies of countries where writers were in prison. They got press coverage and ultimately helped secure the release of writers, particularly those in former Commonwealth countries like Malawi.

Malawian poet Jack Mapanje recalled his spirit lifting when he saw the press clippings of Harold Pinter and others protesting outside the Malawi Embassy in London on his behalf. When he was released, he resettled in England and joined English PEN.

Jack Mapanje

Next Installment: Freedom and Beyond…War on the Horizon

PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move: West to East

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I have attended 32 International PEN Congresses as president of a PEN Center, often as a delegate, as Chair of the International Writers in Prison Committee, as International Secretary and now as Vice President. The number surprises me when I count. The Congresses have been held on every continent except Antarctica. Many were grand affairs where heads of State such as Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, Angela Merkel in Germany, Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal greeted PEN members. Some were modest as the improvised Congress in London in 2001 when PEN had to postpone the Congress planned in Macedonia because of war in the Balkans. PEN held its Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia the following year. At these Congresses writers from PEN centers all over the globe attended. Today PEN International has centers in over 100 countries.

Among the more memorable and grand was the 54th PEN Congress in Canada, held in September 1989 when PEN still held two Congresses a year. The Canadian Congress, staged in both Toronto and Montreal by the two Canadian PEN centers, moved delegates and participants between cities on a train. The theme—The Writer: Freedom and Power—signaled hope at a time when freedom was expanding in the world with writers wielding the megaphone.

54th PEN Congress in Canada, 1989. Front row: WiPC chair Thomas von Vegesack, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman and PEN USA West Executive Director Richard Bray. Back row: Digby Diehl (right) and other delegates.

The literary programs included luminary writers from over 25 countries, including Margaret Atwood (Canada), Chinua Achebe (Nigeria), Anita Desai (India), Tadeusz Konwicki ( Poland), Claribel Alegria (El Salvador), Margaret Drabble (England), Michael Ignatieff (Canada), Ama Ata Aidoo (Ghana), Derek Walcott (St. Lucia), John Ralston Saul (Canada), Duo Duo (China), Harold Pinter (England), Tatyana Tolstaya (USSR), Alice Munro (Canada), Wendy Law-Yone (Burma), Larry McMurtry (USA), Emily Nasrallah (Lebanon), Yehuda Amichai (Israel), Maxine Hong-Kingston (USA), Michael Ondaatje (Canada), Nancy Morejn (Cuba), Jelila Hafsia (Tunisia), Miriam Tlali (South /Africa), and dozens more, and other writers listed in absentia such as Vaclav Havel (Czechoslovakia) and writers from Iran, Turkey, Hungary, South Africa, Morocco and Vietnam. PEN members and delegates attended from at least 57 PEN centers around the world.

The new PEN International President Rene Tavernier, a poet who had been active in the French resistance during World War II, hailed the importance of the writer’s role in upholding freedom of expression around the globe and in confronting central power which restricted individual voices. PEN’s and the writer’s only weapon was the word, he said, and the word must be used in service of “creative intelligence, human rights, lucidity and hope.” Though the twentieth century had seen “the growth of new and atrocious ideologies with their police forces and concentration camps, they could not change the spirit of man, which is what PEN defends,” he said. PEN’s concern was literature and ideas and conversations among writers, who may not always agree.

A goal of the Congress was to expand dialogues among people, especially in Muslim communities in the wake of the fatwa and to expand PEN’s reach into Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. Today PEN centers in those areas have grown exponentially with 33 centers in Africa and the Middle East and 19 centers in Latin America, though participation from these centers in global forums still remains challenging.

Another outcome of the Congress was the formation of the PEN Women’s Network, a precursor to the Women’s Committee established as a standing committee of PEN two years later at the 1991 Vienna Congress. The Canadian Congress organizers had balanced literary panels and discussions among men and women, a response to the growing voice of women in PEN and to the 1986 New York Congress where men dominated the forums. Some opposed a Women’s Committee, including English PEN which voiced concern that it would fragment and divide members when the goal of PEN was to bring people together. English PEN already operated under a guideline that balanced men and women in leadership. PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer wrote that she had “more pressing obligations here, at home in South Africa, towards the needs of both women and men who are writers under our difficult and demanding position, beset by censorship, harassment, and lack of educational opportunities common to both sexes.” But she added that she hoped if a committee did form, it would be in touch with all South African writers.

PEN USA West presented a resolution on South Africa at the Congress, protesting the arrest and treatment of a number of writers, including our honorary member. The resolution passed unanimously in the Assembly of Delegates.

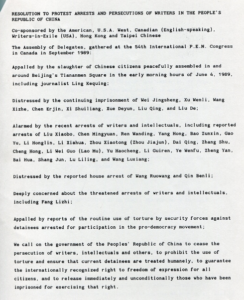

My fellow delegate and I also joined American PEN as well as Canadian PEN, Hong Kong and Taipei PEN in a resolution protesting the “slaughter of Chinese citizens peacefully assembled in and around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square” three months before and the arrest of writers, including Liu Xiaobo and over 20 others. It was feared some of the China PEN members might be under threat. Neither the China Center nor the Shanghai Center were present at the Canadian Congress, but they had been in touch with PEN International. In an official communication the Shanghai Center protested that China was being slandered abroad. Representatives from the two Chinese Centers had demanded an apology from PEN International because poet Bei Dao had been allowed to address the Maastricht Congress (see PEN Journey 3) and they continued to argue that PEN’s main case Wei Jingsheng was not a writer. An apology was not offered, and the resolution protesting the killings and arrests after Tiananmen Square passed with one abstention. Delegates from the China Center and Shanghai Center didn’t return to a PEN Congress for the next two decades, but in the intervening years, individual centers and members such as Japanese writers stayed in touch. In 2001 an Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) formed and gave a place for Chinese writers inside and outside of China to communicate with discussion and debate on freedom of expression and democracy. PEN currently has more than half a dozen centers of Chinese writers, including the China, Shanghai, ICPC, Taipei, Hong Kong, Tibet, Uyghur, and Chinese Writers Abroad centers.

The challenge for PEN has always been how best to use its formal resolutions, written in the language of the United Nations. These are passed then directed to the respective governments, to United Nations forums and to embassies and officials in the countries where PEN has centers and to the media. The effort begins at the PEN International office and then fans out through the centers. The impact of the resolutions vary according to country and to the direct advocacy efforts. However, the climate for such resolutions has altered over the years, and it is an ongoing question what is the most impactful method for effecting change.

At the Canadian Congress the situation in Myanmar/Burma was also highlighted. Our center, along with Austrian, Australian (Perth), and Canadian centers presented a resolution protesting the slaughter of Burmese citizens and the wholesale arrests and imprisonment without trial of citizens, including writers, after the imposition of martial law. I met one of these writers—Ma Thida—in London years later after PEN had advocated aggressively for her release. She’d spent almost six years in prison. A physician, writer and editor and an assistant for Aung San Suu Kyi, she remained committed to freedom for her country. It took another 15 years before the Myanmar government eased restrictions and a civilian government took over. When the political situation in Burma/Myanmar began to open, Ma Thida, Nay Phone Latt and other writers, many of whom had been in prison, formed a PEN Myanmar Center which joined PEN’s Assembly at the 2013 Congress in Reykjavik, Iceland. Ma Thida was its first president, and she now serves on the International Board of PEN.

Ma Thida and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the PEN Congress in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan in October 2014

For me, the outward facing Canadian Congress mirrored my own preparation for moving with my family to London three months later in January 1990. It was a fortuitous time to live in Europe as Eastern Europe was opening to the West. Six weeks after the PEN Congress, East Germany announced that its citizens were free to cross into the West, and the Berlin Wall began to crumble figuratively and literally as citizens used hammers and picks to knock down the looming concrete structure. In fall 1990, I took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to East Berlin, and we too climbed up on ladders with metal rods and knocked down the wall, chunks of which we still have.

Joanne and sons Elliot and Nate at the Berlin Wall, Fall 1990

At the Canadian Congress, PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair Thomas von Vegesack asked that a sub-committee be formed to assist in fundraising. Eight centers—Australian (Perth), Canadian, Swedish, Norwegian, West German, English, American and USA West agreed to help. Because I was moving to London where PEN International was headquartered, Thomas asked if I would head the effort. I told him I wasn’t able to do so but agreed to take on the interim position and help him find a chair and then agreed to take on the task of getting PEN International charitable tax status. I assumed the latter mission would be fairly straightforward, a matter of finding the right law firm to assist. Little did I know the complications of British charitable tax law. Eventually Graeme Gibson, president of PEN Canada, novelist and partner of Margaret Atwood, agreed to head the development effort.

After I arrived in London, I found a law firm. Charitable tax status would relieve PEN of tax bills it found hard to pay and also help with fundraising, but so far PEN had not been able to secure the charitable status. Thomas and I, along with the International Secretary Alexander Blokh, Treasurer Bill Barazetti and Administrative Secretary Elizabeth Paterson met frequently at the PEN International offices at the top of four (or was it five?) very steep flights of stairs in the Charterhouse Buildings where we worked on what turned out to be a two-year project that included the establishment of the International PEN Foundation. The Foundation was allowed to raise tax-exempt funds for the “charitable” work of PEN which could not include perceived “political” work, but only the “educational” aspects.

It took a young American who didn’t know it was impossible to do what we have not been able to do, Antonia Fraser said to me as she joined the first board of the International PEN Foundation in 1992. In a way she was right for I had no idea the complexity of British tax law, quite different than America’s. I wasn’t prepared for the sets and sets of documents and negotiations, the time required to set up a separate organization; on the other hand, the effort opened up the workings of PEN International to me and introduced me to friends I’ve maintained over the decades who also worked on the project. On the Foundation board with me were a majority of British citizens (and PEN members), including Antonia Fraser, Margaret Drabble, Buchi Emecheta, Andre Schiffrin, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson and later Ronald Harwood as well as a few other international members, PEN’s International Secretary, Treasurer and the new PEN President Gyorgy Konrad.

Harold Pinter’s play Moonlight premiered as the first fundraising event of the International PEN Foundation on October 12, 1993 at the Almeida Theater. Dramatically, the lights of the theater burnt out just before the performance, and the play was performed by candlelight.

First International PEN and PEN Foundation brochure.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 5: PEN in London, Early 1990’s

PEN Journey 1: Engagement

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. As Vice President Emeritus of PEN International and former International Secretary, former Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, former President of PEN Center USA West, board member and Vice President of PEN America and the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging with documents, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down some of the memories. I will try in digestible portions to recount moments, though I’m not certain how easily I can contain all these. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of some interest.

February 13, 1989: I was President of PEN Center USA West and on an airplane when I read that Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses was being burned in Birmingham. The next day a fatwa was issued on Rushdie. What was a fatwa, we all asked at the time, as we, along with PEN Centers around the world, mobilized to protest that a head of state was ordering the murder of a writer wherever he was in the world.

November 10, 1995: As Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, I was standing vigil with others outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington, D.C. when word spread that novelist and activist Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

October 7, 2006: My phone rang at 7:30 on Saturday morning. I was International Secretary of PEN International, and the International Writers in Prison Program Director was calling to tell me that Anna Politkovskaya had just been shot and killed in Moscow. We all knew Anna—I’d last had coffee with her at an airport in Macedonia. We worked with her on the situation of writers in Russia and Chechnya and had enormous respect for her knowledge and courage.

January 19, 2007: We were about to begin a PEN International board meeting in Vienna when a call came from Istanbul. Hrant Dink had just been shot and killed outside his newspaper office in Istanbul. Dink was an editor of an Armenian paper and a writer whom members of PEN knew well and worked with on freedom of expression issues in Turkey.

Most writers long active in PEN’s freedom-to-write work can tell you where they were when the news broke on each of these cases. They can tell you because the lives of these writers and many others have been critical in the struggle for freedom of expression around the world.

In sharing memories of PEN, I begin with the writers and with the many friends around the globe who work on behalf of writers who don’t have the freedom to write without threat, imprisonment or death. As colleagues, we are bound together by the belief that truthful writing matters, be it journalism, fiction, poetry, drama, essays because stories and witnessing and creative imagination connect, inspire and shape us. Free expression is fundamental to a free society and is worth defending and expanding.

Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro Wiwa, Anna Politkovskaya, Hrant Dink

My own thirty plus years working with PEN began at a dinner meeting in Los Angeles in the early 1980’s. I was a young writer, new mother, former journalist who’d recently moved across the country from New York City where I taught writing at university and had friends and colleagues. I landed in the land of sun and Hollywood, and though I had a new college teaching job, I knew few people and even fewer writers. Like many who first seek out PEN, I came for the community.

My second meeting was at someone’s home where a presentation was made about writers in different parts of the world who were in prison because of their writing. I was introduced to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. At that meeting, we wrote postcards urging the Chinese government to release Wei Jingsheng, a writer who was imprisoned for “counterrevolutionary” activities, particularly for his essay “The Fifth Modernization” which he’d posted on the Democracy Wall in Beijing in 1978. His manifesto argued that as China was modernizing with four principles of modernization, it needed to include a fifth modernization–Democracy.

As I learned about Wei Jingsheng and the other writers on whose behalf PEN worked, I became more active in the PEN Center on the West Coast of America called PEN Los Angeles Center. I was elected President in 1988. Shortly after the election, I attended my second PEN International Congress in Seoul, South Korea right before the Olympics there. (The first Congress I attended was in 1986 in New York City, where our Center’s members were registered with the foreign delegates. I was active at that New York Congress in the Women’s revolution and the statement that came from the Congress.)

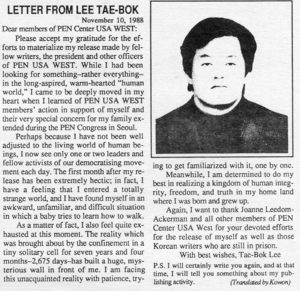

I arrived in Seoul late summer,1988 with our Center’s support for resolutions including one calling for the release of Wei Jingsheng and other writers in China, another resolution addressing writers in prison in South Korea, including our honorary member, publisher Lee Tae-Bok, and a resolution to change the name of PEN Los Angeles Center to PEN Center USA West. The name change had been passed by our center’s previous board but needed approval of the international Assembly of Delegates. It reflected our wider membership in the western part of the United States.

As president of PEN Los Angeles Center, I arrived as a young writer with a small delegation from Southern California, which included the former book editor of The Los Angeles Times and an English professor from UCLA. American PEN, based in New York, the largest of PEN’s more than 60 worldwide centers at the time was headed by Susan Sontag, president. American PEN didn’t want us to change our name and opposed our resolution on the floor of the Congress. While our two centers agreed on the other substantive issues of the Congress, including the problematic situation for writers in South Korea, and though we shared meals, the American PEN delegation, and Susan Sontag in particular, tried to get us to withdraw our name change, including a midnight call to me from Susan. The name change would be confusing, she said, and would take from the national scope of American PEN’s work. In that midnight call I listened to the arguments, then shared our thinking, which included the observation that our membership already came from many states west of the Mississippi, that in a country the size of the United States, PEN allowed more than one center, and for writers 3000 miles from New York, there was value in having more than one center of gravity. In the morning I presented American PEN’s arguments to my delegation, and we decided to go ahead and let our resolution go to the floor of the Assembly.

The representative from East Berlin noted: It would seem the East and West of America get along worse than the East and West of Germany. PEN Los Angeles Center’s resolution for a name change won by a wide margin, and we left the Congress as PEN Center USA West, which years later became PEN USA. I no longer live in Los Angeles but note that only in the past year –2018—did the members of the West Coast PEN decided to merge with PEN America in New York so there is now only one center of PEN in the US.

Most memorable and significant from the Seoul Congress was our delegation’s visit with the family of Lee Tae-Bok, our honorary member. “The house of Lee Tae-Bok’s parents is neat and spare, bedrooms with tatami mats on the floor, a living room with a sofa, a chair, a fish tank. There is no excess in the house, one senses out of choice. But there is an absence, not out of choice, for Lee Tae-Bok has been away in prison seven years. His mother worries that she will not see her oldest son out of prison before she dies,” I wrote in our Center’s newsletter. The family said that Lee Tae-Bok was in poor health and held in a cell four by five square meters, allowed out in the fresh air for only twenty minutes a day and wasn’t allowed to write except one letter a month to his family. His mother lamented the “hypocrisy” of the Korean government which had sentenced her son to life in prison because they said he published communist propaganda and yet they were greeting writers and “honored guests” at PEN’s Congress from Communist countries as well as inviting Eastern bloc athletes to Korea for the Olympic Games.

Digby Diehl and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman meet with the family of Lee Tae-Bok at the Lee home in Seoul in 1988.

In addition to our family visit, PEN Congress delegates petitioned the South Korean government on behalf of those in prison. A delegation from PEN International visited two of the writers in prison.

A few weeks after the Congress, notification reached us that Lee Tae-Bok had been released, though not everyone PEN spoke up for was released. I still remember where I was—I was in New York—when I heard the news, and I remember the elation. Many people worked on Lee Tae-Bok’s behalf so we couldn’t and didn’t take the credit, but we could feel some part of our actions, some push at the prison door helped spring it open. Release is not always the outcome for PEN’s work, but often it is. It is one of the goals. Over all my years in PEN, the release of a writer from prison still evokes a burst of hope and a measure of faith.

[Next installments: the watershed year 1988-1989 as the first global fatwa is issued against a writer, and writers and students in Tiananmen Square square off against China.]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 2: The Fatwa

Duck for a Day

I passed two ducks strolling down the highway on Easter morning—large mallards waddling and chatting with each other, staying on their side of the white-lined shoulder, yet precariously close to the cars whizzing by. They appeared oblivious to the traffic. I wondered where they were going and where they thought they were. They were several miles from water. On their side of the small highway on the Eastern shore of Maryland sprawled a shopping center with a supermarket, restaurants, movie theater. On the other side spread a bit of green field and beyond that more stores and beyond that woods, and beyond that the water—the Tred Avon River which eventually flows out into the Chesapeake Bay.

I was tempted to turn around and try to get a picture, but by the time I could make the turn and get back, they would likely have flown away. Instead, I carry their picture in my mind. I love ducks.

What kind of creature would you be if you were a creature? I would be a duck. Not a lion or giraffe or bear, not a gazelle or panther. No, I’d choose a duck. They can walk and swim and fly and are good at all three mobilities. They are modest, but much smarter and more ingenious than given credit. They have “a remarkable ability for abstract thought,” and “outperform supposedly ‘smarter’ animal species,” according to the Smithsonian. I am fairly certain walking down the highway, they were not debating the Mueller Report or the 2020 U.S. presidential elections, thus demonstrating already a more transcendent point of view.

I’d choose a mallard with the purple-blue wing feathers, the striking green set of feathers around the head (though that is only the male), stepping gingerly with big webbed feet, then gliding onto the water and when the mood strikes, lifting off the water into flight. I could live practically anywhere I wanted in North America, South America, Africa, Australia, Asia. I don’t have enemies except for humans who want to shoot me, and I have a pleasant disposition most of the time. I watch and listen, cooperate well with a group and have an uncanny sense of direction.

Readers, thank you for indulging this moment of fantasy in an effort to lift above the serious, yet endless and tendentious issues on the ground here in Washington.

What kind of creature would you be, at least for a day?

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

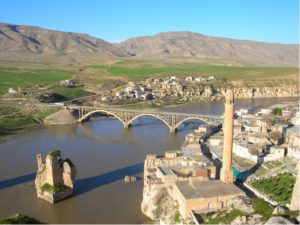

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.