Posts Tagged ‘Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’

PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At the end of September 2005 a Danish newspaper published 12 editorial cartoons which depicted Mohammed in various poses as part of a debate over criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark objected, and by early 2006 protests, violent demonstrations and even riots erupted in Muslim areas around the world. The offense was the “blasphemy” of drawing Mohammed in the first place and the particular mockery of some of the depictions in the cartoons.

The uproar over the Jyllands-Posten Mohammed cartoons quickly drew PEN into the controversy, first through Danish PEN and then through the International PEN office and other PEN Centers. PEN included many Muslim members and numbers of centers in majority Muslim countries. All PEN members and centers endorse the ideals stated in the PEN Charter. However, the third and fourth articles of the Charter which addressed the situation, also at times appeared to contradict each other:

Article 3: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

Article 4: “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world toward a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restrain, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

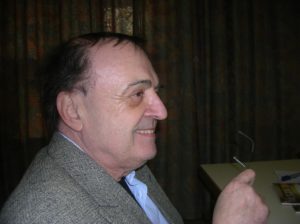

PEN International Board and Staff 2006. L to R: Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Elizabeth Nordgren (Finish PEN), Jane Spender (Programs Director) Sara Whyatt (Writers in Prison Committee Director), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Karen Efford (Programs Officer), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International President), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Britta Junge-Pederson (Treasurer), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair), Chip Rolley (Search Committee Chair), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Peter Firkin (Centers Coordinator) [not pictured: Mohammed Magani (Algerian PEN), Karin Clark (WiPC Chair), Kata Kulavkova ( Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair)

Peace Committee program 2006. Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Veno Taufer (Peace Committee Chair)

At the Peace Committee conference that April, I observed, “The Charter of PEN asserts values that can appear contradictory, but represent the dialectic upon which free societies operate and tolerate competing ideas…In our 85th year, International PEN still represents that longing for a world in which people communicate and respect differences, share culture and literature, and battle ideas but not each other.”

The Danish cartoon controversy led off 2006. For me, the PEN year also included attending the conferences of three of PEN’s four standing committees—the Peace Committee in Bled, Slovenia, Writers in Prison Committee in Istanbul, Turkey (PEN Journey 35) and Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee in Ohrid, Macedonia (PEN Journey 39)—and in May the 72nd PEN World Congress in Berlin, and later a Danish Conference on the Middle East in Copenhagen, the Gothenburg Book Fair in Sweden, a PAN Africa Conference in Dakar, Senegal and a trip to Moscow, where I went to watch my oldest son compete in the European Wrestling Championships and visited Russian PEN on a mission.

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including Alexander Tkachenko, General Secretary, 2006

To Moscow I took just under $10,000 raised by PEN centers and buried in my luggage to help the Russian PEN Center. Vladimir Putin and the Russian government had begun to crackdown on nongovernmental organizations with ties to other countries. One of their first targets was Russian PEN which had opposed the legislation restricting nongovernmental organizations. At the time I was also on the board of Human Rights Watch, a larger organization which was watching closely what was happening to PEN. The government’s attack on Russian PEN came in the form of a freeze on all assets for failure to pay a land tax. Russian PEN argued that it was a legal tenant where it had been conducting business and was not liable for the tax on the land, but the tax office refused to drop the charges. The government threatened to close PEN and take away its office if the money wasn’t paid. An appeal had gone out to PEN’s other centers, which had responded from around the globe not only with protests to Moscow but also with funds for Russian PEN.

I brought in funds just under the amount I would have had to declare. During the wrestling tournament I met with Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko, the General Secretary of Russian PEN, and delivered to him the donation, and he gave me a receipt. The funds stayed off the crisis for then. Charges were dropped. A Russian Minister said, “I don’t understand. I was getting letters from as far away as Argentina!” Sascha answered him: “That is the kind of organization we are.” PEN continued to operate.

In Moscow I also met with Russian PEN members as well as with Turkmen author Rakhim Esenov, who was visiting Russian PEN. I had met Esenov a few weeks before in New York where he had won PEN America’s Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write award. In Turkmenistan Esenov had been charged with “inciting social, national and religious hatred using the mass media” because of characters in his novel The Crowned Wanderer. Set in the 16th century Mogul Empire, the story focused on a poet/philosopher/army general who was said to have saved Turkmenistan from fragmentation. The president of Turkmenistan Saparmurad Niyazov banned the book for portraying the main character as a Shia rather than a Sunni Muslim, and he imprisoned Esenov for several months. I still have the massive Russian language volume he shared with me, a work that had taken him years to write.

L to R: Russian PEN General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko and Russian PEN member outside Russian PEN office in Moscow and Rakhim Esenov, author of The Crowned Wander and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), 2006

At the Peace Committee conference earlier that month I’d presented a paper on the conference theme “The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World,” a broad and challenging topic which had inspired me to peer both backward and forward.

Below is the beginning of that paper with a link to the rest:

My first memory of a PEN meeting was sitting in someone’s living room in Los Angles writing postcards to free Wei Jingsheng from prison in China. At the time in the 1980’s he’d already been in prison several years of a fifteen-year sentence. I had no idea who this writer was thousands of miles away. I barely knew the other writers in that living room. On the coffee table would have been PEN’s Case List, which at the time was white sheets of paper stapled together.

We wrote and stamped our post cards for Wei and other writers that afternoon. I’m sure we were provided with background on his case. I pictured these cards fluttering into a jail somewhere in China and perhaps even into the cell of this stranger to let him know we had taken note of him and cared what happened. Looking back on the blue-sky afternoon as we sipped sodas and ate crackers and cheese, I see our act as a bit fleeting, an effort to imagine the fate of another writer who didn’t have our freedom to write and speak…[continue reading here]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN Journey 39: Spiritus Loci—Literature as Home

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

[From address at Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference September, 2006:]

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

Last year at this conference, I packed in a rush, left behind a pair of shoes, but in the process got a title for a story.

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

I don’t yet know what story will emerge, or maybe only this brief talk will emerge, but Macedonia makes the title work, at least to my mind. I Left My Shoes in England…that doesn’t work…I Left My Shoes in France?…No. I Left My Shoes in the United States…please. I look forward to discovering who left the shoes and what the circumstances were and most of all what Macedonia has to do with the story.

Ohrid, Macedonia, setting of PEN International Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee conference, 2006.

Exploring the conference theme spiritus loci will be part of the journey. As writers we know the power of place in literature and in our lives. The Latin term meaning the local spirit of a place is not always easily defined, but it relates to the geography, the history, the architecture and the people, who are both shaped by and shape the place. The ancient Romans thought every location had a spirit, some benign where people would live longer, happier lives and some evil and destructive of human well-being.

Today in a world grown smaller and more connected by jet travel, the internet, the global village, the cyber global village, with the blending of cultures and commerce worldwide, spiritus loci is perhaps a more fluid concept and to a younger generation, even a digital concept. On the internet I discovered a recording studio with the name Spiritus Loci; it moved from place to place recording people’s music wherever the musicians felt most comfortable.

Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) Dimitar Basevski (President Macedonian PEN), and Kata Kulavkova (Macedonian PEN & Chair PEN International’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

It is still the writer who can best capture a place and a people and render that spiritus loci for the reader. The best writers unveil the unity between location and character so that the writer’s version becomes the backdrop for understanding the place for generations to come, whether it be Tolstoy’s Russia, Balzac’s France, Dickens’ England, Achebe’s Nigeria, Toer’s Indonesia, Fuentes’ Mexico.

Through PEN we have the opportunity to know writers and their literature from around the globe and also to visit and experience the places from which they come. I’ve had the pleasure of coming to Macedonia four times and to this most beautiful city of Ohrid because of PEN.

With 144 centers in 101 countries, PEN has members who live and operate in most regions of the globe, with different histories, geographies, races, religions, cultures, but with the common spiritus loci of ideals. Today, these ideals, which were developed between World Wars, continue to promote a shared humanity on earth. PEN members work to use “what influence [we] have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations…to do [our] utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the idea of one humanity living in peace in the world.” This mandate provides its own kind of spiritus loci no matter where one lives. It is a compass that points both to the ground we occupy and the future we hope to achieve.

Meeting at 9th Ohrid Conference of PEN International’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, 2006

Macedonia and its neighbors have been at the center of the struggle for those ideals in the last decade. In 2001 when the fires from the Balkan wars were still smoldering, PEN postponed its International Congress in Ohrid until the conflict in Macedonia subsided. Fortunately we were able to be hosted at a Congress in Ohrid the following fall. When PEN members look at that troubled time in Macedonia only a few years ago and at the current devastating conflicts in the Middle East, it is worth reflecting on how thought evolves, how cultures are translated to each other, and how we can best apply the spiritus loci of our ideals.

When a people find their home destroyed whether by natural disaster or by war, the concept of spiritus loci is problematic. The role of literature is especially important at that time. Literature provides a home in the mind and reveals the humanity we all share—the spiritus loci of the human spirit. Let us not underestimate this power of ideas and writing to transform.

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia. Perhaps the character will return to find the shoes and also to discover what Macedonia might teach. I am at least lucky enough to have returned, and I look forward to seeing what I will learn…wearing my new shoes.

—Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Next Installment: PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN Journey 38: PEN’s Work On the Road in Kyrgyzstan and Ghana

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

There have been a number of conferences and a few Congresses in PEN I’ve regretted not being able to attend. One was the Women’s Committee conference June 2005 in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan right after the 71st Bled Congress. As International Secretary, I have notes and reports from that conference. Nine years later in the fall of 2014, PEN held its 80th World Congress in Bishkek, a Congress I did attend. The Women Writers Committee led the way for International PEN into Central Asia. Later in 2005 members of the Women Writers Committee also met at the International PEN conference in Ghana which I did attend.

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, site of PEN International’s Women Writers Meeting in June 2005 and Accra, Ghana, site of PEN International’s African conference and also meeting of African women writers, November 2005.

First, Bishkek: The President of Bishkek PEN Vera Tokombaeva was concerned about the circumstances of writers in Central Asia since the breakup of the Soviet Union. She suggested to the new Women Writers Committee (IPWWC) chair Judith Buckrich that PEN hold a women writers meeting in Bishkek. Many of the institutions which had enabled writers to publish had vanished, and the status of women in the region had grown worse. Young writers from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan who were members of the PEN center were troubled by the decrease in the number of women working creatively. Only a handful were left.

PEN Women Writers Committee Chair Dr. Judith Buckrich and International PEN Board member Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN)

Bishkek PEN did a study highlighting the problem. Central Asian women writers were struggling with poverty, it said, and literature was no longer published unless self-published with limited distribution.

“Women writers are now mostly on their own. They have fallen into a cultural vacuum,” the conference proposal noted. “They are not in contact with colleagues outside their own country and know nothing of the state of culture in the world. In the meantime the global community has begun to pay attention to Central Asia because its difficult geopolitical situation could lead to the rise of violent, ultra-religious and fundamentalist ideologies into the area. And it is partly the lack of modern local literature that makes the region a breeding ground where alien ideologies can take root among young people. Flourishing modern literature could be the means to disseminate democratic ideas and social awareness.”

International PEN raised funds for the conference whose theme was “Women and Censorship.” Women from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan as well as from Finland, Norway, Switzerland and Australia gathered. The discussion focused on the access to education for women, access to literature and the formation of support groups and publishing cooperatives within and outside the region and ways to overcome censorship and self-censorship. The group addressed external pressures on what women should write and considered ways and means to access funding for women writers.

Attendee Kristin Schnider, President of Swiss German PEN, noted, “Following the discussion on the main topic, women and censorship in Central Asia, I learned just how hard it is for the strong and determined women I met to overcome censorship and self-censorship within their societies…First and foremost a woman is perceived as a mother and wife, tending the family. So much so that women feel they are confronted with the choice between being either creative or getting married. Women are not supposed to enter politics…[and] if women insist on writing they are supposed to stick to detective stories or romantic topics.”

In a discussion “The Situation in Central Asia: Women and Society and Economic Censorship,” moderator and documentary film maker Dalmira Tilepbergenova from Kyrgyzstan, noted: (translated from Russian)

“Patriarchy foundations have always been strong in Asia…My disclosing of gender inequality by the example of cinematograph is not casual. Because firstly cinematograph is a corporative sort of creative work and thus the problem of relations between men and women shows very clear and strikingly there. Second, I as a film director have to constantly deal with the problem of my work. Since Kyrgyzstan became independent, our cinematograph has passed through the period of its clinical death to its reestablishment. New names have already appeared and new films have been shot. But strange relations between our cinematograph and gender policy have existed up to now. Unwillingness of men to see women in the spheres usurped by men occur…instinctively. And this instinct is as strong as the instinct of self-preservation. Firstly, when the woman is engaged on an assisting job position in our cinematograph, everything seems to be all right. But as soon as the woman shows a desire to make films independently, the friendly atmosphere of men around her turns into syndicate of plotters. Men at once start to blame the woman for her excessive ambitions, incompetence, and uselessness. Men also criticize her private life. The woman’s desire to make films is considered as diagnosis of having deficit of sex.”

IPWWC Chair Judy Buckrich of Melbourne PEN reported the Bishkek conference was “a fantastic opportunity,” and said the committee had already begun planning for a meeting of women writers on the African continent to follow the Senegal PEN Congress in 2007. “The meetings are important in expanding the horizons of PEN to women who are not members of PEN but who PEN supports as part of its belief to support writers in difficult circumstances,” she noted.

Women Writers meeting at 2005 PEN Ghana conference including Veronica Uzoigwe (Nigerian PEN), Zeinab Koumanthio Diallo (Guinean Center), Ekbal Baraka (Egyptian PEN), Muthoni Likimani (Kenyan PEN), Kristin Schnider (Swiss German PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitiker (PEN International Executive Director), Jane Spender (PEN International Programs Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary/American PEN)

In December 2005 International PEN’s conference in Accra brought together 36 writers, a number of them women, from 13 of PEN’s 17 African Centers to prepare for the 2007 Senegal Congress. Supported by UNESCO and hosted by Ghanaian PEN, the conference aim was to begin developing a plan for sustained programs and collaboration among the African centers and to select a theme for the Congress. While PEN Senegal would act as the host center, the World Congress was a joint effort of PEN’s PAN African Network. African members of the Women’s Committee held an additional meeting to address the challenges facing women writers in Africa and to plan for the larger IPWWC conference in 2007.

In preparing for the Ghana conference, I returned to the shelves of African literature I’d read years before and pulled some of the books which first took me to Africa before I ever arrived on the continent—Ama Ata Aidoo’s No Sweetness Here, Ayi Kwei Armah’s Fragments, Charles Mungoshi’s Waiting for the Rain. In my address to the conference, I included a quote from Ghanaian writer Kofi Anyidoho’s prose poem Akofar only to discover when I arrived that Kofi Anyidoho was on the program.

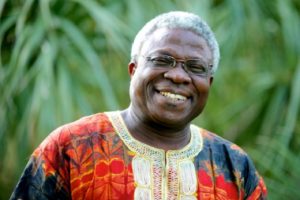

Speaking Ghanaian Professor and poet Kofi Anyidoho, seated Frankie Asare-Donkoh, Secretary PEN Ghana

From Akofar:

Words are birds. They fly so fast too far from the hunter’s aim. Words are winds. Sometimes they breeze gentle upon the smiles our hearts may wear for joy; they fan the sweat away from fever’s brow; they lull our minds to sleep upon the soft breast of earth. Yet soon too soon words become the mad dreams of storms. They howl through caves through joys into shrines of thunderbolts. They leave a ghost on guard at memory’s door. Therefore gently…gent-ly…Akofa, gen-t-ly…Take care what images of life your tongue may carve for show at the carnival of weary souls.”

The poem spoke to the themes and mission of PEN and the gathering of writers who understood that words transport over time and place and history, that words cross borders and have the power to connect us to each other and to ourselves. It is words, shaped into images and ideas, that survive wars and famine and political unrest if we are vigilant and protect them and circulate them and translate them.

Top to Bottom: Zeinab Koumanthio Diallo (Guinean PEN), Frankie Asare-Donkoh (Ghanaian PEN), Veronica Uzoigwe (Nigerian PEN)

I also quoted from Ghanaian poet Ayi Kwei Armah’s Fragments:

“Where are you going,

go softly.

Nananom,

you who have gone before,

see that this body does not lead him

into snares made for the death of spirits.

You who are going now,

do not let your mind become persuaded

that you walk alone.

There are no humans born alone.

You are a piece of us,

of those gone before

and who will come again.

A piece of us, go

and come a piece of us.

You will not be coming,

when you come,

the way you went away.

You will come stronger,

to make us stronger,

wiser,

to guide us with your wisdom.

Gain much from this going.

Gain the wisdom

to turn your back on the wisdom

of Ananse.

Do not be persuaded you will fill your stomach faster

if you do not have others’ to fill.

There are no humans who walk this earth alone.”

The poem reflected the aspiration of PEN and the meeting among participants who, as writers, often did work alone, yet understood we were all part of a larger community. For any community of letters to thrive and survive, the freedom of the individual writer had to be protected.

At that time in Africa over 230 writers in 34 countries were listed as PEN cases, excluding Egypt, which was counted in the Middle East, though the President of Egyptian PEN also attended the meeting. The large majority of cases were journalists arrested as critics of the authorities or as whistleblowers on corruption. Journalists also ran afoul of the “insult laws” which were on the books in 45 of the 53 African countries. Because of the difficult state of publishing in Africa, journalists were the group of writers with realistic possibilities of being published. Countries of most concern then were the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Libya, Somalia, Tunisia and Zimbabwe, none of which had active PEN centers, though a Somali-speaking PEN center did exist in London, and Zimbabwe PEN had existed but was inactive with its President poet Chenjerai Hove having to live in exile. (Today there are PEN centers in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, and Tunisia though the situation in some of the countries remains problematic.)

The Network of African Freedom of Expression Organizations (NAFEO) had formed just two months before the conference with 33 freedom of expression organizations attending a press freedom conference in Ghana. The aims of the network were similar to PEN’s whose Writers in Prison Committee would interact and assist when the network began to function.

The attendees at the Ghana conference shared experiences of their PEN centers, particularly in providing writing and reading programs in schools. Ghana PEN had a robust program in the schools as did other centers. The delegates agreed that the goals and work of PEN in Africa should include expanding freedom of expression, helping to lower barriers to publishing and disseminating African literature, cultivating new voices and increasing access to literary creation. The means to achieve these goals were part of the discussion, including cultivating new voices by working with youth writing clubs, bolstering recognition and excellence in literature by awarding literary prizes. Delegates planned for these discussions to continue among the African PEN Centers, facilitated when possible by International PEN. They also planned to expand the ideas and work at the 2007 PEN Congress.

Writers and visiting students at 2005 PEN International Conference in Accra, Ghana. African PEN Centers attending conference: African Writers Abroad, Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somali-Speaking, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia as well as American and Swiss German and International PEN facilitating and note taking.

Ghana PEN organizers Frankie Asare-Donkoh, General Secretary and Frank Mackay Anim-Appiah, President with PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

During the Ghana conference the possible theme for the 2007 Congress was debated and discussed, including:

—Literature and the Environment/ Literature and Ecology

—Literature and Emancipation (women, political, financial)

—Freedom of Expression and Conflict Prevention

—African Writing in a New Age, In and Out of Africa

—The Role of Literature in the Creation of Peace (with sub-themes “The crisis of reading and readership” and “Literature for children”)

—Writers Role in Peace Building in Africa and World & Literature

—Literature and the Oral Tradition (with the subtheme of the environment)

—The Writer’s /Literature’s Role in Peace-building in Africa and the World

—Literature of Exiles/ Exile Literature

—The Roles of Literature and Publishing

—The Word, the World and Human Values

—Challenge of African Literature Today

—Being a Writer in Africa

—Writer in Age of Globalization (cultural diversity)

—Survival of Literature in New Millennium

—African Writing in New Age: In and out of Africa

—Writers and Prevention of Conflict

—Writers in Their Role in Encouraging and Promoting Literacy in Africa (Responsibility and Role of Writer)

—Literature and Conflict management in Africa and the World

—Freedom of Expression and Global Diversity

—Writers in a World in Crisis (diversity, literacy etc)

The theme finally agreed for the 73rd PEN World Congress in Dakar was: The Word, The World, and Human Values.

Elmina Castle, built in 1482 as Portuguese trading settlement, became principle holding prison for slave trade on Cape Coast, Ghana for three centuries.

The highlight of the conference was a long road trip to Cape Coast (also known as the Gold Coast), where the first European (Portuguese) explorers arrived in the 1400s. The Portuguese built the Castle of Elmina there which still stands on the rocks above the sea. In this new/old land the Portuguese discovered gold and also began acquiring human beings to trade for European goods. British, Dutch, Danish, Prussian, and Swedish traders soon followed and built other forts along the coast. Elmina Castle was turned into a prison for men and women who were sent shackled through “the door of no return” into slavery. From this point, as well as from Gorée Island off the coast of Dakar, Senegal, the slave trade flourished for centuries as European and other traders sold men and women and goods into the Caribbean and North and South America.

“Slave Exit to Waiting Boats” in Elmina Castle, Cape Coast, Ghana; Kadija George, President of African Writers Abroad Center standing in front of a “door of no return.” The back of her shirt reads: “Literature is the most beautiful of countries.”

The ghostly white fort of Elmina with its iron-barred cells with peep holes to the ocean facing west and the crashing surf on the rocks silenced us as we moved through these portals of history. The several hour ride back to the city was much quieter than our impatient journey to the Coast.

In Tanzania an exchange between poet and audience in the oral and performed poetry often begins:

“I give you a story.”

Audience: “I give you another.”

“I came and I saw.”

Audience: “See so that we may see.”

This power to see and invoke, to enter the rhythm of the human heart and dance there for a time with another as partner is what literature does and what PEN celebrates and tries to protect.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 39: Spiritus Loci—Literature as Home

PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At PEN’s 71st World Congress in June 2005 over 275 writers from 88 PEN Centers gathered from around the world in the idyllic setting of Bled, Slovenia where history had been made 40 years before. In 1965, PEN had held its Congress in Bled, the first in Eastern Europe since the Second World War. Russian writers visited PEN for the first time. At that 33rd World Congress, American playwright Arthur Miller, who’d recently passed away in 2005, had been elected the first and only American President of International PEN.

Lake Bled in Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International’s 71st World Congress, 2005

In 2005 the global dynamics had changed. PEN now had active centers in most of the countries in the former Communist Eastern bloc, including in Russia. The European Union (EU) was in its ascendancy; 2005 marked Slovenia’s accession into the EU. Globalization was bringing benefits but also threats to the cultures of smaller countries.

Reception 71st PEN Congress in Bled, 2005. L to R: Frank Asare Donkoh (Ghana PEN), Jane Spender (Program Director PEN International), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), Alfred Msadala (Malawi PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (PEN Executive Director), Dan Khayana (Uganda PEN), Bao Viet Nguyen-Hoang (Suisse Romand PEN) [Photo credit for many photos: Tran Vu]

“We live in an age when many preconceived ideas, nurtured for centuries and ostensibly immutable, are no longer valid,” noted Slovene PEN President Tone Peršak. “The linguistic and cultural image of the world is in flux and civilization as a whole, under the influence of globalization, is taking on a new character. These events are also echoed in discussions within PEN centers…They guided us in our selection of the main topic for discussion at the Congress, namely the issue of linguistic and consequently cultural diversity of the world. The topic is proposed as a question: does linguistic diversity stimulate or hinder cultural development? Is it a curse or a blessing that made possible the emergence and encounter of various world views, different emotional responses to the human destiny, and finally also brought about the formulation of different schools of thought and philosophical doctrines?

“We regard the question of linguistic and cultural diversity also as a human rights issue. Attempts to unify and subject all aspects of life to uniform standards and norms is viewed as a very questionable encroachment on these rights. One of the topics is therefore the question of the need to protect languages and cultures, and that means also the smallest ones which may be on the verge of extinction. Let us also draw your attention to literature’s role in the preservation of the memory of the cultural landscape, which has been undergoing considerable changes and in some cases may even disappear forever…[Is] literature a kind of lingua franca which could and should contribute to a better mutual understanding and insight into the different cultures and nations that sustain cultural diversity?”

These were questions without definitive answers, but questions that occupied writers from dozens of cultures and languages in the Congress’s literary sessions. [At PEN Congresses, the main sessions and the Assembly of Delegates were usually translated into PEN’s three official languages—English, French and Spanish—and also the language of the Congress host.]

PEN International Congress Bled, Slovenia 2005. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Monika Van Paemel (Belgium (Dutch-speaking) PEN), Alexander Blokh (French PEN and former PEN International Secretary), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Jiří Gruša (President, International PEN)

A number of the delegates had before been to Bled, home of PEN International’s annual Writers for Peace Committee conference, hosted by Slovene PEN. During the Cold War the Peace Committee, founded in 1984, provided one of the only open forums for dialogue between writers from the East and West.

“Let us learn the language of our neighbors so that we all may better come to know and understand our neighbors and forestall incomprehension and conflict,” the Peace Committee and the Congress organizers urged.

In my own address to the Congress as International Secretary, I relied on the prevailing metaphor of the bridge, using an example close to home:

I recently crossed a soaring new bridge in Boston, Massachusetts, a bridge at least 14-years in the making. This bridge spanning the Charles River was the result of what is called the Big Dig, a project anyone who has lived in or regularly visited Boston has come to think of as the Eternal Dig for it is hard to remember when a large segment of downtown wasn’t under construction. But at last there is this soaring bridge with stanchions into the sky in gracious arcs and at night a blue light shining up into its cables as it rises above the city. There is also an elaborate network of freeways and tunnels underground.

I sometimes think International PEN is a bit like the Big Dig. For much of the last decade we’ve been reconstructing ourselves, trying to reflect in our governing structures the expansion that PEN has experienced across the globe, an expansion brought on in part by the opening up of societies after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the lifting of the so-called Iron Curtain. This expansion has also been enabled by the linking of the globe through the internet. International PEN has instituted a Board, been through a long range planning process, revised rules and regulations, and while we still have construction going on and probably always will, I’m hopeful that we too will start to see more and more of the benefits of all this work…Throughout we’ve continued to witness remarkable activities from our Centers…

This year I’ve been telling people that PEN is a place where cultures don’t clash but communicate. PEN members may not always agree, in fact frequently don’t agree, but the fellowship among members can keep that disagreement from turning into confrontation. At our best PEN’s forums offer a place where the energy of competing ideas releases light, rather like that spectacular blue light which shoots upwards on the cables of the grand bridge in Boston.

Arthur Miller once described PEN: “With all its flounderings and failings and mistaken acts, it is still, I think, a fellowship moved by the hope that one day the work it tries and often manages to do will no longer be necessary. Needless to add, we shall need extraordinarily long lives to see that noble day. Meanwhile we have PEN, this fellowship bequeathed on us by several generations of writers for whom their own success and fame were simply not enough.”

The work included substance and form, the latter focusing on the organizational structure which allowed the work to go forward. At the Bled Congress the delegates approved procedural reforms, broke into workshops to discuss PEN itself and global and regional issues, and were introduced to PEN’s first Executive Director, who would begin the following month. After an extensive search, the board and staff had agreed to hire Caroline Whitaker (née McCormick) who had worked in theater development, had a degree in literature and was coming to PEN from the Natural History Museum where she was Director of Development.

Writers in Prison Committee and Workshop Sessions, PEN International Congress, Bled, Slovenia, June 2005

At the Congress seven candidates from Algeria, Colombia, Croatia, France, Finland, Japan, and Russia ran for positions on the International Board, and Mohamed Magani (Algerian PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), and Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN) were elected.

The Congress discussed and passed over 20 resolutions and actions challenging the situations for writers in Algeria, Basque region of Spain, Belarus, Burma, China, Cuba, Iran, Maldives, Mexico, Nepal, Russia, Syria, Tibet, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam as well as resolutions relating to the attacks on journalists in war zones and the crackdown on internet writing in Tunisia where the World Summit on the Information Society was to be held that fall.

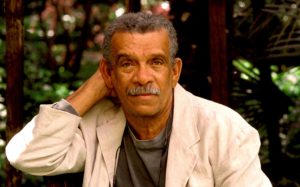

The Congress also noted the tenth anniversary of the death of PEN member Nigerian writer Ken Saro-Wiwa. International PEN President Jiří Gruša noted: “We are living in a time of extraordinary threats to writers and the freedom to write. In the ten years since our colleague Ken Saro-Wiwa was executed in Nigeria, hundreds of writers and journalists around the world have died by violence. Crackdowns on internet writers and anti-terrorism legislation have named writers and chilled freedom of expression in a number of countries.

“While our colleagues in countries such as Myanmar, Cuba, China and Belarus continue to struggle against conventional governmental censorship and repression, writers also face the threat of moral violence in countries from Mexico to Iraq and new pressures associated with writing and publishing on the internet.”

Among the guests at the Congress were Colin Channer, who introduced the prospective Jamaica PEN Center which was voted into PEN at the subsequent 2006 Congress in Berlin.

And for the first time since the Tiananmen Square massacre June 4, 1989, a writer from the People’s Republic of China attended as a representative of the new Independent Chinese PEN Center whose members included writers from inside and outside of mainland China. I include below much of his talk which rings truer than ever.

Wang Yi* addressed the Assembly, noting that this was the first time in 16 years “the voice of a non-official and independent Chinese writers’ group could be heard, a group that is independent or at least strives for its independence, that is free or at least longs for freedom and that tries to perpetuate the freedom of expression in the face of great political pressure…

Wang Yi (Independent Chinese PEN Center)

“I come here heavy-hearted without blessing, because there is no reconciliation between a free writer, an independent intellectual, and his government. I come to Bled representing those who have been disgraced, who have stood in the shadow of terror and the peril of political oppression, and who have yet never resigned but have insisted upon their freedom of speech and writing, such as Mr. Liu Xiaobo whose work has been not allowed to be published and who has not been allowed to go abroad. I also come for myself, who experienced in the sixteen years after Tiananmen a long period during which memories have been erased forcefully and silence has been ordered. This has been a time during which mothers, who lost their sons and daughters at Tiananmen, have not been allowed to weep…

“To me and my colleagues, writing is a rescue plan for the hostage. Writing means dignity and freedom; it is kind of belief. But we cannot rescue ourselves, even when we have courage and when justice is on our side in the face of institutional arbitrariness…

“Our salvation depends upon that higher community, depends upon common universal values that we share as writers, as free people and as intellectuals. It is the source of liberty and imagination…

“We are disappointed to see that some European governments are gradually abandoning free values and lessening their criticism of the despotic regime in Beijing. For a common benefit they abandon the writers, reporters, dissidents and orators who are imprisoned…

“According to the Independent Chinese PEN club, more than 50 writers and reporters are currently in jail…

“I want to mention two points: the first one is the belief that through writing, we can enlighten and preserve basic human values. Second, there is a global realistic linguistic environment. These two points make me think that the persecution of Chinese, Tibetan, Uighur and other minority writers reaches across borders to become an international issue…There is only the suppression of the right to freedom of expression and the persecution of human beings, which needs to be rooted out, and the victim needs to be consoled and supported…

“The Chinese government’s suppression of writers has accelerated in recent years, since the beginning of the Internet era…pen names and pseudonyms are prohibited. With this act, the last bastion of self-protection is destroyed.

“Every morning, the Communist Party’s propaganda department issues a list of prohibited news to the media. Whoever dares to break the taboos will get into big trouble. As the government stifles the mouths of the media and betrays the public, it also tampers with the truth in historical textbooks and deceives the children in school. An increasing number of courageous writers, reporters and public figures are daring to challenge the status quo so more and more of them have been thrown into jail on charges of committing the crime of “instigation and subversion of the state” or “disclosing state secrets” to “hostile forces…

Liu Xiaobo and Yu Jie (Independent Chinese PEN Center)

“Among the harassed and persecuted are also the president of ICPC and his deputy, Mr. Liu Xiaobo* and Mr. Yu Jie*. Under such circumstances, you cannot but regard the Chinese writer as a hostage…

“I come to Bled hoping to present myself as a writer, but I am indeed only a hostage…One of the reasons that I definitely wanted to come is that I believe we all belong to the same world. In this world, the state, the glory and the lawful right all belong to that higher spiritual origin that makes us, without regret, proud to be a writer.”

*[Wang Yi, deputy Secretary General of ICPC 2003-2007, has been imprisoned in China since December 2018, serving a 9-year sentence for “activities disobedient to the government control” and “inciting subversion of state power and illegal business.” Wang Yi is a writer and a Christian pastor. Liu Xiaobo, the second President of ICPC, was sentenced in December 2008 to an 11-year prison sentence as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power.” He was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in custody June 13, 2017. Yu Jie, a celebrated writer, was one of the drafters, along with Liu Xiaobo, of Charter 08, which set out a democratic vision for China; he was arrested and tortured in 2010 and immigrated to the U.S. in 2012. He is author of Steel Gate to Freedom: The Life of Liu Xiaobo.]

Lake Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International 71st World Congress, 2005

Next Installment: PEN Journey 38: PEN’s Work On the Road in Kyrgyzstan and Ghana

PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

In pulling out papers from 2005 of PEN conferences and the 71st World Congress, I came across two documents that told a very human story in PEN and a coincidence of life that I share here:

71st PEN World Congress 2005, Bled, Slovenia, Round Table Papers

The first paper I skimmed was a talk I’d given as PEN International Secretary at the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference in Ohrid, Macedonia in September 2005; the paper included the testimony of a PEN member at the end. The second text I read was from the Round Table Papers of the PEN Congress a few months before, in June 2005. This paper was on the Congress theme Tower of Babel: Blessing or a Curse? The paper was the first in that publication and was written by celebrated Nigerian poet Niyi Osundare who speculated on what the world would be should there be just one language and then meditated on what in fact the world was. Shared below are excerpts from Dr. Osundare’s paper, “The Blight and Blessing of Babel:”

“A one-language world would be too simple, too linguistically neat, too unrealistic. And, I daresay, too unnatural. For everywhere in nature there is a tendency towards fission and mutation on an intra-and inter-generic basis. Variety is not only the sauce of life; it is also its source…

Nigerian poet Dr. Niyi Osundare

“Yoruba culture (the culture in which I was born and raised, and one that I know best) understands the necessity of diversity and inevitability of varieties in different aspects of human life. Hence the saying “Mee l’Oluwa wi” (Many, says the Lord) and “Ona kan o w’oja” (There are countless routes to the same market), both of them short, handy variations on a longer proverb “Oju orun t/egberun eye fo lai farakanra (The sky is wide enough for a thousand birds to fly without colliding). Corroborating this pluralist perspective is the folktale about the Tortoise, ever cunning and self-centered, who one day decided to capture all the wisdom in the world and seal it up in one pot for his own use in an effort to become the wisest being in the world. Of course, his project ended up in a laughable disaster as his pot fell to the ground and exploded while different fragments of the imprisoned wisdom dispersed in different directions, free for all, unmonopolisable. In an essentially pluralist Yoruba worldview, phenomena exist by mutual definition; a thing, a person loses its sense of proportion when there is nothing else to compare it with. The trajectory of life hardly ever follows one straight and narrow path; it must confront the crossroads, experience the thrills and tortures of decision and indecision, before arriving at the juncture of choice. And for the act of choosing to take place, there must be more than one…

“Literature (and the arts generally) is, no doubt, a powerful weapon in the struggle against the blight of Babel. By endowing our airy thought with that ‘little habitation’ and ‘name’ (hail Shakespeare, one of the supreme healers of the wounds of Babel), by generating universal sympathies, globalizing the particular and particularizing the global, by producing that music of the spheres whose winds stir the eaves in different lands, by evoking images which touch hearts across cultures, by articulating those humane values that are essential to human freedom everywhere in the world, by constantly lifting the human spirit and enriching, interrogating human reality with the supple possibilities of fiction…literature strives to restore some of the lost potentialities of Babel. For every significant writer is a bridge-builder of a kind, a witness, a participant-observer, an advocate of a truly humane future.

“No doubt, the phenomenon of Babel has left its fragmentations and dispersals. But it has also bequeathed to humanity a panoply of sounds and letters, an astounding (even if confounding) array of tongues which challenges the tyranny of uniformity and monotony of methods. It has necessitated the building of bridges across diverse tongues and cultures, these bridges being, in a way, a horizontal alternative and antidote to the vertical impossibility of the Tower itself.”

L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary) and Kata Kulavkova (Chair PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

Dr. Niyi Osundare, a Nigerian PEN member, had moved to New Orleans for specialized education for one of his daughters and was also a member of the African Writers Abroad PEN Center. Recounted here is my talk to the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee a few months after the Bled Congress, in September 2005. Only as I recently read the end of my paper did I grasp the connections and the range of PEN’s reach and work. My observations at the time:

The theme of the 8th Ohrid P.E.N. Conference—Writer Within and Without a Homeland—struck a particularly sonorous chord as I was preparing to come here.

In the U.S. the question of homeland has been on the national consciousness for the past month as one of America’s most diverse and multi-lingual cities—New Orleans—has literally disappeared. Its population evacuated as the city sank into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. A large portion of the Gulf coast also fled in the face of Hurricane Katrina. Over a million people dispersed throughout the land in one of the largest displacements in the nation’s history. Many will never return to their homes.

In Europe and Africa, Asia and Latin America even larger displacements have occurred in the last century, often because of war, famine, politics, and also weather. All of us remember the disappearance of towns and villages and whole sections of coasts in the countries hit by the tsunami last December.

When a home is suddenly gone, family scattered, livelihood and career and ambitions all uprooted, one is forced to consider what endures, and what one can take with him. Home moves from a physical place to a place in consciousness.

The ability to speak with others and to tell the story is especially important and makes the idea of language as homeland compelling, also imagination as homeland, literature and art as homeland, and particularly relevant to PEN, a community of fellowship as homeland.

I’d like to read a message to PEN’s Africa Writers Abroad Centre from a Nigerian writer trapped in New Orleans:

This is my first real internet access since the disaster struck…I can’t thank you enough for your concern and care. It’s been all so overwhelming. My wife and I are alive and, after passing through five horrendous “evacuation centers”, have been allocated to the Red Cross shelter in Birmingham, Alabama. The nightmare of the past seven days is simply unimaginable. We very narrowly escaped drowning in our own house. Pursued by an 8-foot high toxic flood water (15 feet in the street outside our door), we were forced up a stuffy, airless attic, where we were holed up for 26 hours, with no food, no water, no prospect of any rescue. We were only saved by the fortuitous intervention of a neighbor who heard our shout for help when he came round with his rescue boat to pick up something from his own house. With life vests provided by him, we managed to swim out of our house, leaving everything we had behind. Right now, all our clothes, books, academic and professional credentials, travel documents, computers, manuscripts, etc are submerged in the dirty waters of the New Orleans flood. Hell has no other name… We deeply appreciate your concern. Kindly pass on our gratitude to all on your list serve.

Yours in the Eye of the Storm

[Niyi Osundare]

I’m told he has been overwhelmed by the outpouring of concern. While the concern and offers of assistance can’t replace what was lost, it can fill in some of the spaces in the heart.

In the U.S. those displaced are at least relocated in the same country and for the most part speak the same language, though the difference in accents has its challenges. What has been heartening has not been the help of government agencies, but the outpouring of citizens in communities all over the nation and abroad. One would wish this empathy would prevail and continue.

The ability to imagine and to reach out to another and try to see from the other’s point of view is one of the elements of great literature and also of great people. This empathy is a value around which PEN has developed and one which PEN at its best embodies.

A community spread across 99 countries, shaped by different nationalities, cultures, races, religions, and languages, PEN is a fellowship of writers who appreciate the importance of telling a story and defend the writer’s freedom to tell it as he sees it and to tell it in the language of his choosing. Language is the writer’s tool, expressing the music of his thoughts and sounding the chords of his imagination.

Language, imagination and fellowship—all are a kind of homeland that can survive the elements and can even survive politics and war, a homeland, one of whose addresses we like to think is at P.E.N.

Dr. Osundare and I didn’t know each other at the time though perhaps met briefly at the Bled Congress which was attended by more than 275 writers. I know many of his colleagues from Nigerian PEN and at the time from the African Writers Abroad PEN. I made the connection only as I reviewed the papers. Dr. Osundare is now a professor at the University of New Orleans.

Delegates at PEN International World Congress, Bled, Slovenia, June, 2005. L to R: Remi Raj (PEN Nigeria), Dan Kayhana (PEN Uganda), Frankie Asare Donkoh (PEN Ghana), Alfred Msadala (PEN Malawi)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

PEN Journey 35: Turkey Again: Global Right to Free Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN’s work attests to the power of the individual and also to a particular vision of globalization that advocates the global right to free expression, a right that supersedes national restrictions.

In February 2005 Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s most noted writers, received threats and had his books burned by nationalist groups objecting to comments he made to a Swiss magazine while he was abroad. He referred to an Armenian “genocide.” While the Armenian community rallied to defend him, their support heightened certain nationalists’ protest in Turkey. Orhan wasn’t in Turkey at the time and hoped the turmoil would die down, but a government official in southern Turkey ordered the seizing of his books from local libraries so that they could be destroyed; it turned out later that there were none of his books in those libraries.

Novelist Orhan Pamuk and Sara Whyatt, International PEN Director of Writers in Prison Committee (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At Pamuk’s request International PEN kept quiet publicly at first. In mid-April Sara Whyatt, International PEN’s Director of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and I had lunch with Orhan in London to discuss how PEN could help if the threat escalated. I was International Secretary of PEN at the time. We agreed that publicity at this stage could exacerbate the situation; however, we explained that PEN centers could work behind the scenes by direct contacts with their governments, and PEN would be prepared to step into public action should the need arise.

Pamuk intended to stay outside Turkey until late April/early May, but then he would be returning home to Istanbul. Sara stayed in touch with him and shared a plan for action if the threats resumed on his return. Meanwhile we told him PEN would continue to lobby for a change in the Turkish Penal Code that allowed the charges. Key PEN centers, who had good relations with their own governments, and centers from countries with influence in Turkey would make approaches. London’s WiPC would make similar approaches to Turkish officials in Ankara and also through mechanisms at the United Nations, OSCE, and the European Union (EU). At the time Turkey was hoping to become a member of the EU and was attempting to align its judiciary codes with those required by the EU. PEN also worked with the International Publishers Association .

PEN prepared a statement on the situation in Turkey from early 2005 and kept it updated with news and recommended actions for the over dozen PEN centers ready to respond on this case. There was also press guidance should the centers receive queries. Meanwhile PEN continued to work on the other cases of over 70 writers and intellectuals charged or in prison in Turkey, which had long been a country with a revolving door of writers harassed, detained, attacked and sent to prison.

On April 1, 2005 World Peace Day the Turkish press reported:

The investigation against author Orhan Pamuk due to this statement saying, ‘One million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds were killed’ [in Turkey] has ended with a case in which he is accused of violating article 301 of the new Penal Code (same as famous article 159 in the former one) “Insulting Turkish nationality” and with the demand of being imprisoned between six months and three years. The first hearing will take place at Istanbul Sisli No. 2 First Instant Criminal Court on December 16, 2005.

The Public Prosecutor claimed that Pamuk’s remarks in Switzerland’s Das Magazin were an infringement of Article 301/1 of the Turkish Penal Code which states that “the public denigration of Turkish identity” is a crime and that those found guilty should be given sentences ranging from 6-36 months.

With threats renewed by the Public Prosecutor and a lawsuit filed against Pamuk that could result in a three-year prison term, Orhan finally gave PEN the green light to launch its campaign. PEN centers mobilized globally, including in Turkey.

“It is a disturbing development when an official of the government brings criminal charges against a writer for a statement made in another country, a country where freedom of expression is allowed and protected by law,” I noted at the time.

Pamuk’s hearing in December, 2005 was approximately ten years after renowned Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal had been called to trial on similar charges in January 1995. Pamuk told a colleague he would underline two things in his statement:

1. What I said is not an insult, but the truth.

2. What if I were wrong? Right or wrong, do not people have the right to express their ideas peacefully in this Turkey?

Eugene Schoulgin, PEN International Board Member and Müge Sökmen (Turkish PEN) at WiPC Conference, Istanbul, 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the judicial hearing, PEN members came to stand witness to the proceedings, including WiPC Chair Karin Clark, Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar, and International PEN board member and former WiPC Chair Eugene Schoulgin. Armored police officers escorted Orhan as protesters hurled a barrage of eggs and jumped on the car, punching the windshield.

PEN’s observers reported at the time: “The scenes around the first appearance of Orhan Pamuk before Sisli No. 2 Court of First Instance on 16 December 2005 at 11:00 were marked by constant shouting and scuffling turning ugly and violent at times. As those attending the proceedings left the court, eggs were hurled along with insults from the nationalists and fascists among the crowd lining the pavement across the street. This in full sight of the national and international media which had turned out in full…

“The courtroom was packed with well over 70 people—among them famous Turkish writers such as Yaşar Kemal and Arif Damar, and representatives of the European Parliament, several diplomats, members of Turkish and international freedom of speech organizations. The aggression and heckling inside and outside the court did not abate…”

The session ended after an hour and 15 minutes with an adjournment because the Ministry of Justice said that it needed more time to decide on the legal basis of the trial.

Hearing the news of postponement, International PEN President Jiří Gruša declared, “It is unbelievable that Orhan Pamuk, one of Turkey’s best known and eminent authors, is in this situation. What it indicates is a complete disregard for the right to freedom of expression not only for Pamuk, but also for the Turkish populace as a whole. This decision bodes ill for other writers who are being tried under similar laws.”

He added, “PEN demands that the trials against all writers, publishers and journalists be halted and that the laws under which they are being tried be removed from the Penal Code. We also call on the Turkish authorities to put a definitive end to the penalization of those who exercise their right to freedom of expression.”

Hrant Dink, Journalist and Editor-in-chief Argos and Hilde Keteleer (Belgian Flemish PEN) at PEN WiPC Conference in Istanbul, Spring 2006 (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

At the time there were 14 other writers, publishers and journalists on trial under the newly revised “insult” law for criticizing the Turkish state and its officials. These included Ragip Zarakolu, publisher of books by Armenian authors and Hrant Dink, editor of an Armenian language newspaper, who was assassinated two years later.

For Pamuk the charges were dropped in January 2006, though on a technicality rather than on legal grounds protecting freedom of expression. The widespread opposition to Pamuk’s prosecution by PEN and other organizations succeeded, but as Turkish PEN President Vecdi Sayar noted in The New York Times: “There are many people abroad who fail to see beyond Orhan Pamuk’s trial. Saving a writer like Orhan Pamuk from prosecution may stand as a symbolic example on its own. But it is not an overall resolution for other intellectuals and writers that still face similar charges in Turkey.”

In March 2006 Orhan was the featured guest at PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee’s biennial conference held in Istanbul, hosted by Turkish PEN.

Writers in Prison Conference Istanbul 2006. L to R: Karin Clark (International PEN Chair WiPC), Sara Whyatt (Director WiPC), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary International PEN), and Sara Wyatt (Photo credit: Sara Whyatt)

On October 12, 2006 Orhan Pamuk won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

It could be said that the case of Orhan Pamuk signaled a long ride to the end of Turkey’s potential membership in the EU. In September 2006 the European Parliament called for the abolition of laws such as Article 301 “which threaten Europe’s free speech norms.” In 2008, the law was reformed, but according to the reform, it remained a crime to explicitly insult the “Turkish nation” rather than “Turkishness,” and in order to open a court case based on Article 301, a prosecutor was required to have approval of the Justice Minister; a maximum punishment was reduced to two years in jail. In November 2016 the members of the European Parliament voted to suspend negotiations with Turkey over human rights and rule of law concerns. In February 2019 the European Union Parliament committee voted to suspend accession talks with Turkey.

Turkey continues to be one of the most problematic countries for writers, especially on certain topics. While Turkey’s Penal Code relaxed for a while, allowing more space and freedom for writers, in the last years, the code and its execution has grown more onerous than ever.

*****

In that spring of 2005, I attended an event celebrating Press Freedom Day (May 3), hosted by Italian PEN in Venice. There I shared testimonials from writers on whose behalf PEN had worked. I share these again here:

** Cuban journalist and poet Jorge Olivera Castillo was conditionally released from prison in December 2004 after serving 20 months of an 18-year sentence. He wrote:

Your solidarity has been a light in the darkness. Thank you for having elected me as an Honorary Member…[I send] to all of you my gratitude for your messages of support and your unflagging concern.

** Nkwazi Mhango, Tanzanian journalist in exile, wrote:

Believe it or not tears are gushing as I am writing this message. No way in whatsoever manner my family and I can reciprocate your love and commitment to our plight. THANKS AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN MORE.

** On a sadder note the following was received from Tunisian internet writer Zouhair Yahyaoui, who died suddenly in March 2005 from a heart attack after he’d been released from prison:

Your email gave me once again a lot of hope for a better future in my country at a time when the dictatorship uses all illegal and barbaric means to make us give up and abandon all forms of protest…The fact that I continue to struggle to obtain our right to freedom of expression, here in Tunisia, is thanks to support of members of International PEN and other international organizations. Thank you again to you, to the Writers in Prison committee of International PEN and to all the PEN clubs all over the world who have supported me enormously during my imprisonment and who continue to do so.

** And from Chinese writer Jiang Qisheng:

… I am not a remarkable person. I am just an ordinary guy who did something extraordinary because it was the right thing to do…If my own case has any special significance it is only that it forces people to face a highly embarrassing fact—the fact that even now, in the dawn of the 21st century, a Chinese citizen can be imprisoned for what he says.

** I ended with a passage from the book This Prison Where I Live, the collection of prison writings drawn together by International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In the afterword Malawian poet Jack Mapanje, who himself was in prison during the autocratic rule in his country, tells how bits of news managed to get smuggled into him in his concrete cell filled with spiders and cockroaches, scorpions and bats and bat droppings.

I found the note, unusually fat…I found a bulletin of typed world news and two poems by Brecht…Pat also enclosed two honorary membership cards from International PEN’s English and American centers, issued in London and New York respectively. They each bore my name. I had been made a member of PEN. Well, well, well!…

Then there was a cutting from Britain’s Guardian newspaper. Lord Almighty! A picture of Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, Antonia Fraser, and other members of English PEN reading from my book of poems in protest at the Malawi High Commission in London! It must sure have an effect, I thought. Ten thousand miles away, among the cockroaches of the prison where I lived I felt utterly humbled. Shattered. Such generosity, such warmth I surely did not deserve. All for one slim volume of poems? Why hadn’t I written more poems? I was dumbstruck. Despair vanquished. ‘I am belonged,’ I heard myself whisper.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN Journey 34: Diyarbakir and Beyond—Finding Byways for Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN has always been about building bridges, finding the byways of fellowship among writers whose currency is language and imagination and whose hope is that even with radically different histories and backgrounds, writers might find a way to sit down across a table from each other and share stories and listen to each other and thereby have a beneficent influence on the way they and their societies see themselves and others.

It is an idealistic goal that has been battered in PEN’s hundred year history, and yet the organization continues; the dialogues continue, and writers from over 100 countries continue to meet and talk, even from countries whose governments have not found peace in decades. There have been moments of seeing that optimism realized, at least for a time, and also seeing it smashed.

The next section of these PEN Journeys covering the years 2004 (PEN Journey 33) through 2007 (August) will focus on my years as International Secretary of PEN International. I will travel through events chronologically, the number of events increasing considerably as the role demanded. I will try to knit these together as we continually try to do as an organization.

International PEN Seminar on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

In January, 2005 we held our first board meeting of the year in Vienna where PEN President Jiří Gruša had recently taken up the position as Director of the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna which hosted us. The formal board meeting itself took place in the basement of the hotel restaurant where we were staying. Around the table in the cozy space where we sat on chairs and on a long booth was PEN’s diverse board from Algeria, Colombia, France, USA, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Croatia, Australia, Norway and Japan. The search for an executive director, the new financial and employment systems going into place in the office, an upcoming meeting in Stavanger, Norway with the old Cities of Asylum Network, and an upcoming meeting in Diyarbakir, Turkey with Kurdish and Turkish PEN—all populated the agenda as did the omnipresent discussions on fundraising.

For me, the imminent departure of my Marine son from the combat zone in Iraq hovered in the corner of my mind. We were staying at a pension hotel with small rooms—single bed, dresser and nightstand; I could almost touch the walls on both sides. Outside it was snowing. I’d come to Vienna unprepared for the snow and had bought at a sale a large puffy yellow coat that now draped across the bed for warmth. At night in the dark as I fell asleep, I thought about my son and one night dreamed a desperate dream. Then the phone rang; it was 1:30 in the morning. My husband’s voice woke me. “Wheels are up!” he declared. “They are on their way home!” I still remember the moment, lying there in the dark, snow glistening in the light through the small window and feeling as though the walls had suddenly expanded and a weight lifted that I hadn’t been fully aware I was carrying. The memory…the snow, the Cathedral we passed each day in the square and at dusk in the evening, the puffy yellow coat…

I was wearing that same coat as snow fell later that month in Washington, DC the day my son finally pulled into our driveway. I was sitting on the front porch swing in the snow waiting for him, thinking about the hotel room in the dark, the restaurant basement where we helped craft a conference for writers from the hostile parties in Turkey and another to find sanctuary for writers fleeing oppression—all these memories are wrapped together in a moment of return and of the spirit lifting and life opening a corridor to walk down.

Czech PEN 80th Anniversary in Louvre Cafe where PEN members met in 1925. L to R: Playwright Tom Stoppard, PEN Int’l President Jiří Gruša, Czech PEN President Jiří Stránský.

The next meeting I attended that winter on February 15, 2005 celebrated the 80-year anniversary of Czech PEN. In Prague Jiří and I toasted the endurance of his PEN Center which had been founded by Karel Čapek and 37 Czech writers on that day in 1925. Czech PEN had survived the Second World War, the Cold War, the Soviet occupation and finally the liberation. Former prisoner, playwright and PEN member Václav Havel had become President of the country and his good friend and also prisoner Jiří Gruša was now President of International PEN. Under the auspices of the Minister of Culture, we met with Havel and playwright Tom Stoppard, himself Czech, and Jiří Stránský, President of Czech PEN at the Louvre Café where the original PEN gathering had taken place. Later, the Mayor of Prague hosted a reception with Czech PEN members in the Old Town Hall where he opened an exhibition celebrating “Eighty Years of the Czech PEN Club.”

The following week Writers in Prison Director (WIPC) Sara Whyatt and I traveled to the city of Stavanger, Norway which sat on the sea with a harbor and ships at dock. The Stavanger meeting brought together PEN and members of the now disbanded International Parliament of Writers, an organization founded after the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. The Parliament of Writers had developed a program to house writers in cities of asylum, but the Parliament of Writers no longer functioned. Many of the cities, however, still wanted to continue their hospitality for writers at risk. Stavanger itself hosted writers, including poet and novelist Chenjerai Hove, who’d been president of Zimbabwe PEN until he’d had to flee the government of Robert Mugabe. Hove was a fellow at the House of Culture in Stavanger until he passed away in 2015.

Stavanger, Norway, February, 2005 setting for birth of International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN)

Helge Lunde, director of the Stavanger International Festival of Literature and Freedom of Speech convened PEN, representatives from the old Parliament of Writers and representatives from some of the cities that wanted to continue the program. In a several day meeting, the outlines of what would become the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) were laid down with PEN as the vetting organization for applications and also a source of hospitality when writers arrived in their new temporary homes. ICORN remains active today in partnership with PEN in over 70 cities which promote and protect freedom of expression and host writers and artists at risk by providing housing, an income, literary arenas, scholarships and grants. PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and ICORN regularly hold biennial meetings together.

Writer Liu Binyan, a founder and first President, Independent Chinese PEN Center

The following weekend at Princeton University the relatively new Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), founded in 2001, honored Liu Binyan, one of its founders and first President. ICPC’s members live both in China and abroad. The PEN Center gave them the ability to talk with each other and hold programs together, often in Hong Kong. Because of his writing and criticism of the Chinese Communist Party, especially after Tiananmen Square, Liu Binyan had not been allowed to return to China after an academic stay in the U.S. Though he never saw China again, in the U.S. he wrote and worked as Director of Princeton University’s China Initiative. (Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo was also a founder of ICPC and its second president.) At the dinner at the Princeton Faculty Club, ICPC members and China scholars presented Liu Binyan the book Living in Exile, written by distinguished essayists in China and abroad and dedicated to Liu who had spent considerable time in detention and in and out of labor camps. Later that year Liu Binyan passed away at his home in New Jersey.

In March “The International PEN Diyarbakir Seminar on Cultural Diversity” convened the largest and most ambitious conference that quarter in the primarily Kurdish southeast of Turkey. For years the Writers in Prison Committee had focused on cases in this dangerous region where fighting between the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and the Turkish military had resulted in multiple imprisonments and killings. However, a rapprochement appeared to be expanding between the government and Kurdish citizens. In this space, PEN International had been working with Kurdish PEN and Turkish PEN to prepare this historic meeting of the two centers, along with PEN’s leadership of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC). For the first time Kurdish writers and Turkish writers would speak side by side from the same stage in Kurdish and Turkish with translations of each language.

Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jane Spender (PEN International Program Director), Carles Torner (Vice Chair Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee).