Posts Tagged ‘PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee’

PEN Journey 45: Dakar, Senegal: The Word, the World and Human Values

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Program for PEN International’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal, July 2007

PEN International’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal July 2007 celebrated the first Pan African PEN Congress with over 200 writers gathered from over 70 countries around the theme “The Word, the World, and Human Values.” The theme had been developed by PEN’s African centers who assisted in the planning of the Congress which brought together writers from every continent as well as from across Africa.

The setting was grand on the rugged Atlantic coast at Le Meridien Hotel. Government luminaries, including the President of Senegal Abdoulaye Wade and Prime Minister Cheikh Hadjibou Soumaré greeted delegates at the opening and closing ceremonies in the tiered auditorium where the Assembly of Delegates conducted PEN’s business. Ministers of Culture, Information and Foreign Affairs hosted dinners in the evening as did the President and Prime Minister.

Because PEN monitored the human rights situation in countries, particularly regarding freedom of expression, PEN vetted carefully countries where it held its Congresses. Senegal had prosecuted four journalists the past year, but none were in detention, and PEN Senegal and the International Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) were advocating to abolish defamation laws used to repress writers across the continent. Senegal in general was an open society for writers. On the few occasions when PEN hosted Congresses in countries with more repressive regimes, it took no assistance from the government and used the occasion to advocate on behalf of the writers.

The 73rd Congress marked the end of my term as PEN International Secretary. At my first Congress as International Secretary, I’d opened with the image of a bridge soaring into the sky, a bridge that had taken decades to construct. I had suggested that for the last decade International PEN had been building an organizational bridge into the 21st century. Having occupied the position of International Secretary for three years on a daily basis, I could attest that PEN was a robust, though occasionally fragile, organization whose bridges across cultures were real, whose joints were welded by the principles of the PEN Charter and by the fellowship among writers.

For me, memories abounded—memories of the ancient city of Diyarbakir, Turkey where Kurdish and Turkish writers translated each other side by side for the first time; the gathering in Hong Kong where writers from mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the diaspora, along with other writers from around the world, met and shared ideas and literature; and the memory of the dungeons of Gorée Island with its dark doorway to the Atlantic, similar to “the door of no return” on Ghana’s Cape (Gold) Coast where the most basic human rights had been violated centuries before when men and women were shipped as slaves to other countries, including to my own.

At the Congress PEN members traveled to Gorée Island off the coast of Dakar to see and to pay homage to this history and through PEN’s work to act on behalf of freedom and human dignity today.

Visit to Gorée Island, Senegal. L to R: Carles Torner (Catalan PEN), Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN), Lucian Kathmann (San Miguel PEN), Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Mamadou Tangara (Gambia.)

A Nobel Laureate in science once said, “Discovery consists in seeing what everyone else has seen and thinking what no one else has thought.” That could be said of the writer whose imagination saw bridges between people and cultures where others saw clashes and conflict.

Before each Congress I made a point of reading histories of PEN, particularly the history of the place where PEN was holding its Congress. The 73rd Congress was only the second time PEN’s whole international body had met in Africa. Forty years before a PEN delegate at the 35th Congress in Abidjan, Ivory Coast recalled ascending the stairs of the Congressional Hall between a double row of guards dressed in scarlet and gold with raised sabers. At that Congress PEN members took special notice of writers in prison in Communist and noncommunist countries. There were not many PEN centers in Africa then, but PEN Senegal existed. At the Congress the prior year in New York City in 1966, delegates from the Ivory Coast and Senegal had attended as had observers from Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria. By 2007 PEN had 15 centers in Africa, including in those countries whose writers had visited the New York Congress. Today PEN has 28 African centers.

At the Dakar Congress, writers from regions who hoped to develop PEN centers observed, including Uighur writers, Afar-speaking writers and writers from Tunisia, Bahrain, Iraq and Jordan, all of whom eventually formed PEN centers. Forty years ago International PEN also had observers from the Soviet-bloc. In all these instances, PEN had acted as a bridge to writers who aspired to share their literature and to work for freedom of expression in their societies.

PEN International President Jiří Gruša addressing PEN Assembly of Delegates at 73rd Congress, 2007.

In Dakar, International PEN President Jiří Gruša noted, “International PEN and its Centers are glad to be gathering in Senegal, a country which holds literature in high regard, in part because its first President Leopold Senghor was the internationally renowned poet and also a Vice President of International PEN.”

Mbaye Gana Kébé, Senegal PEN President, affirmed, “Senegal has remained a welcome land at the crossroads of all civilizations. In addition to that we have its democratic ideal and respect of human rights. This Congress taking place here consecrates a lasting and beautiful tradition of African hospitality.”

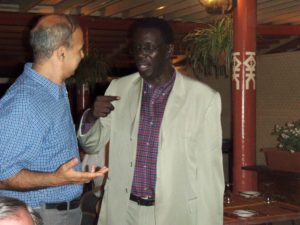

International PEN Board Member Mohamed Magani (Algerian PEN) talking with Alioune Badara Bèye (General Secretary Senegal PEN).

The Congress theme “The Word, the World, and Human Values” was explored thorough round table sessions including “Literature and the Oral Tradition” and “The Role of Contemporary African Literature in Intercultural Dialogue” and at International PEN’s first literary event “Freedoms” held outside under the stars. Hosted with TrustAfrica, a new African foundation that promoted peace, economic development and social justice, the evening and the panels featured writers from across Africa, noted Senegalese PEN Vice President Amadou Lamine Sall and General Secretary Alioune Badara Bèye who were instrumental in arranging the Congress. Writers included Bernard Dadié (Ivory Coast), Jean-Baptiste Tati Loutard (Congo), Fernando d’Almeida (Cameroon), Dieudonné Miuka Kadima Nzuji (Congo), Tanure Ojaide (South Africa), Frédéric Pacéré Titinga (Burkina Faso), Aminata Sow Fall and Pr. Abdoulaye Elimane Kane (Senegal), and Jack Mapanje (Malawi).

In the hotel’s meeting rooms, PEN’s standing committees adjourned. The Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), chaired by Karin Clark (German PEN), focused on criminal insult and defamation laws, particularly in Africa. These laws endangered writers and resulted in imprisonments. During the previous year WiPC had followed 1100 cases worldwide of attacks on writers, ranging from killings, long term detentions, threats, and harassments. Around 320 of those had been in Africa.

PEN also brought attention to the refugee crisis in Iraq with an appeal for translators, writers and journalists who were being targeted for death because of their work. In a resolution supported by American PEN and passed unanimously, International PEN urged the US to protect these refugee writers and translators and to increase funding for UNHCR and other refugee services and remove barriers to resettling Iraqi refugee writers and intellectuals.

The Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC), chaired by Kata Kulavkova (Macedonia PEN), considered the mounting threats to linguistic diversity in an English-dominated world. Delegate Esther Allen (PEN America) presented “To Be Translated or Not to Be: Globalization, Translation, and English,” a major survey of barriers to the exchange of literature and entrance into the international literary marketplace. The Assembly of Delegates passed a resolution calling on UN member states to comply with international conventions on linguistic rights.

International PEN Women Writers Committee Conference, Dakar, Senegal, July 2007.

The Women Writers Committee (IPWWC), chaired by Judith Buckrich (Melbourne PEN), met during the Congress and also at its own conference right after the Congress to examine the challenges faced by women writers, especially as related to freedom of expression and censorship, particularly in Africa. The writers also discussed women’s literacy and educational opportunities and explored the publishing potential for voices which struggled to be heard.

PEN’s Peace Committee, chaired by Edvard Kovač (Slovene PEN), met with an appeal to bring writers in countries at war together in an exchange of literature and ideas such as at a recent meeting between Turkish and Kurdish members

The Writers in Exile Network, chaired by Haroon Siddiqui (PEN Canada), reported that PEN continued to assist resettling writers under threat, often at universities, and also through partnership with the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN).

International PEN’s Executive Director Caroline McCormick and her team worked before, during and after the Congress on regional development. “International PEN is working in partnership with its African Centers to address challenges which they have identified in the region. Essential to this work is the role of continued engagement with reading, writing and ideas in bringing about change and empowering civil society.”

Each African center had its own history and focus though many overlapped. PEN Senegal, the first and oldest center in Africa, was dedicated to raising the profile of young and new unpublished writers and published an anthology of young writers and actively promoted work through its publications and competitions. The center had the advantage of a permanent writers house which was a drop-in center and focal point for the writing community and also accommodated visiting writers.

Guinean PEN had been established by the Women Writers Association of Guinea, which made it one of few African centers that had majority of women writers as members. Headed by Zeinab Koumanthio Diallo, President of Guinea PEN, the center ran its own museum and cultural center and raised the majority of funds through income-generating activities, including performances and cultural activities with a focus on literature and on raising awareness of social issues to include communities who didn’t normally have access to the world of literature. Projects included promoting reading in rural agricultural communities and using literature to support the rights of women and girls.

PEN International’s next regional focus would be Latin America in anticipation of the 2008 Congress. After a vigorous debate at the Congress, the Assembly of Delegates voted to move the 2008 Congress from Oaxaca, Mexico because of challenges to freedom of expression there to Bogotá, Colombia, hosted by Colombian PEN which was monitoring closely, along with International PEN, the situation for writers there.

Members of PEN International Foundation Board, final meeting. L to R: Fawzia Assaad (Suisse Romand PEN), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director), Karin Clark (German PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (PEN International President), Britta Junge Pedersen (PEN International Treasurer), Eric Lax (PEN USA West).

The work of the 73rd Congress included the final disbanding of the International PEN Foundation which had served its purpose for over a decade as a charitable entity that existed with its own board alongside PEN International and enabled PEN International to receive charitable donations. Now that British charitable tax law had changed, PEN International, which was headquartered in London, could finally be incorporated as a charity.

The work of the Assembly of Delegates included elections of:

—International Secretary Eugene Schoulgin (PEN Norway), former WiPC Chair and International PEN Board member,

—Treasurer Eric Lax (PEN USA West), former International PEN Board member and former President of PEN USA West,

—International PEN Board members: Mike Butscher (Sierra Leone PEN), Haroon Siddiqui (PEN Canada), Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN) and Kristin T. Schnider (Swiss German PEN),

—Vice Presidents: Margaret Atwood (PEN Canada) for service to literature and Niels Barfoed (Danish PEN) for service to PEN.

PEN International Board Meeting and Staff in Dakar, Senegal, July 2007.

Three new PEN centers were welcomed: Iraq, Jordan and Afar-speaking.

The Assembly adopted twelve resolutions from the Writers in Prison Committee focusing on the imprisonment of writers in China, Tibet, Iran, Uzbekistan, Eritrea, Cuba, Turkey, Tunisia and Vietnam, the killing of journalists in Mexico & Afghanistan and the forced closure of television stations in Venezuela.

One unexpected controversy arose just a few weeks before the Congress when the British government conferred a knighthood on Salman Rushdie. The act stirred disputes in literary and political circles which threatened to follow us to the Congress. We came prepared should questions arise. I don’t recall now if the question was asked at the closing press conference where Jiří and I sat in our new African dress which had been given to us by the Congress hosts. Along with the President of Senegal PEN we recalled the successes of the Congress and the African programs which PEN International committed to continuing.

Rather than revisit the Rushdie controversy, I quote here PEN International’s response from Vice President and Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer: “International PEN deplores the reaction of extremists to the honor conferred upon one of the world’s great writers, Salman Rushdie, by the Queen of the United Kingdom for his services to literature. The appalling reaction from extremists threatens not alone the principle of freedom of expression as a basic tenant of justice, but seeks to decree the violent end to the life of a writer, solely on the grounds of written words that did not call for any aggression against any group or individual.”

My personal memories of the impressive Dakar Congress include being driven around in a limousine as International Secretary. Because PEN Board Member Eric Lax was hobbling on crutches with his foot in a cast, he also hitched a ride. I would have been happy to go on the bus, but we both appreciated the gesture.

Before each PEN Congress while I was International Secretary, I studied French. I hired a tutor and talked with her for hours, practicing conversation and comprehension and jotting down what I might want to say. I understood that it was important to know the language of so many of PEN’s members, especially when the Congress was in a French-speaking country. I didn’t do the same with Spanish because my Spanish was more remedial, but I had studied French at university and so had some base. French colleagues used to say, “Your accent is cute and you are fearless,” which I think was a nice way of saying you’re not very good, but at least you’re trying.

Before I came to the Dakar Congress, I had taken out my notebook from French lessons and copied on a single page the phrases I thought I might want to say at some point. When I arrived at the opening ceremony, I was seated on the dais along with Jiří, PEN’s Vice Presidents, the President of Senegalese PEN and the President of Senegal. I had not been informed that I was expected to give a speech, but my name, along with Jiří’s, was on the program. I knew Jiří didn’t speak French, and I felt it would be insulting for neither of us to speak in one of the languages of the country. That morning I’d tucked my sheet of phrases into my bag, and as I sat there, I glanced at the accumulation of sentences; they were a kind of speech so for the first few minutes I spoke in French then said, “Now I’d like to shift to English so I can speak better from my heart.” Everyone had translation equipment.

When the closing ceremonies arrived, the same situation arose. With the Prime Minister of Senegal also on the dais, I was again listed on the program to speak. However, this time Senegalese PEN had written remarks for me in French, and I stepped over to my nearby colleagues at French PEN to practice.

PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman addressing Assembly of Delegates at 73rd PEN Congress, July 2007.

To close out this final memory, I share here a portion of my report to the Congress. Each International Secretary and President and Board member and Staff member brings his/her talents, skills and affection to this organization which is held together in part by ideals and friendship. In marking progress, no one diminishes the work that came before. I continue to note in wonder the improbability of an organization of writers connected around the globe in 150 centers in more than 100 countries surviving for a century. With gratitude I recognize those who have come before and kept the organization together and those who come after and add to the bridges and structures or whatever metaphor suits at the time. Here is a brief summary of my journey those years as International Secretary:

As an organization we have grown in the past three years, both in numbers of centers, scope of activity, and size of the Secretariat. We have worked to strengthen the infrastructure of the London office so that it can better assist the centers and can coordinate the international work of PEN. We have put financial systems in place for budgeting and have expanded fundraising, and have established employment procedures and contracts for staff and transparent criteria for our own grant-making.

The Board, which now meets monthly by phone, has worked, along with the Staff and myself, in this process. I want to take this moment to thank the Board whose members work hard on your behalf and each of whom has always said yes when asked to take on a task. I’ve also had the pleasure of working with a wonderful staff, first Jane Spender, who has now retired and sends her best and with the highly qualified team of Caroline McCormick, Sara Whyatt and now Frank Geary and Karen Efford and newer members Tamsin Mitchell and Emily Bromfield…I want to thank former International Secretaries Alexandre Blokh and Terry Carlbom who have always been available when I’ve sought counsel. And I want to thank so many of you in the centers who have helped me in the work and my home center in America for sustained support. Finally we all want to thank Senegalese PEN for its work in putting on this Congress and all the African centers who participated in this effort.

To finance PEN’s growth we have raised funds from new funders and from existing funders, who have signed onto the expanded program for International PEN and have given us larger grants…

I’ve had the pleasure of working with and visiting many of you and your centers over the last three years…One of the greatest pleasures of working with International PEN has been developing friendships around the globe.

PEN is only as strong as its centers. We have been working through our regional program on a one-to-one basis with centers in Africa this year to develop strategic plans. Through the Board we have also been in touch with centers whom we have not heard from in long time to see if they still exist and to find out how we might help them. Through the workshops at the Congresses and in the consultations last year with the whole membership, we have developed for centers a guide to good governance which we will share later at this Congress. Most PEN centers already operate according to the principles of transparent membership criteria, regular elections, rotation in office, and governance by a constitution, but other centers need assistance in this area.

PEN began as a club of writers committed to the ideals which developed over the years. But a club does not mean that qualified writers should be kept out of the work of PEN or that PEN should be an exclusive Academy. There has always been the balancing of PEN as a club and PEN as a nongovernmental organization (an NGO.) Each center chooses its activities, but internationally, PEN operates as an NGO. That is why we have consultative status at the United Nations. Clubs do not receive this status. As an international organization we work to achieve goals related to civil society—the goals of promoting literature and defending freedom of expression. The work of International PEN, through its committees and through the centers and writers who chose to participate in the international work, serves these goals.

This year Caroline and I visited UNESCO several times and are happy to report that UNESCO officials are enthusiastically recommending PEN’s partnership under the framework agreement be renewed for another six-year period. They specifically praised PEN for its “significant modernization.”

At a PEN Congress in 1966 the Mexican novelist Carles Fuentes took note of “the improbable spectacle of 500 writers—conservatives, anarchists, communists, liberals, socialists—meeting not to underline their differences or to enumerate their dogmas, but to bear witness to the existence of a community of spirit while accepting diversity of interests.” That is still what PEN is and what PEN represents to the world.

The theme of this Congress—The Word, The World and Human Values—resonates and was chosen by PEN’s African centers. I am particularly honored to be finishing my term in Africa, for African literature and the literature of African American writers have had a significant influence on my own work as a writer. I’d like to end with a verse from Senegal’s great poet and first President and also International PEN Vice President Leopold Senghor, from his elegy written after the assassination of my countryman Martin Luther King. Senghor’s life offered a kind of bridge in the world. Through his life and his words, he showed how an individual and a writer can in fact enhance human values.

From Senghor’s “Elegy for Martin Luther King”:

“As the Reverend’s heart evaporated like incense and his soul

Flew like a diaphanous rising dove, I heard behind my left ear

The slow beating of the drum. The voice and its sharp breath close to

My cheek said: ‘Take up your pen and write, Son of the Lion.’

“And I saw a vision…”

You must read the poem to see the vision, but I can tell you it is a vision very much in the spirit of PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 46: Wrapping Up

PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

After PEN’s Asia and Pacific Regional meeting in Hong Kong February 2007, I flew to Tokyo for a two-day visit with members of Japanese PEN, along with International PEN board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori. We met with Japan PEN’s board, and in the evening I shared a stage and conversation with Mr. Hisashi Inoue, chairman of Japan PEN and one of the country’s well-known playwrights. Part of our discussions explored the possibility of Japanese PEN hosting an International PEN Congress. Only once before, in 1984, was the World Congress held in Japan.

International PEN Board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori

Housed in an impressive building in Tokyo, Japan PEN was one of International PEN’s largest and most active centers with one of the more interesting histories. Founded in November 1935 on the eve of a tumultuous period in world affairs, Japan PEN members committed to the PEN ideals of freedom of expression and “one humanity living in peace in one world.” By 1935 Japan had left the League of Nations in the wake of the Manchurian Incident and was moving towards international isolation, a direction that concerned liberal literary figures and diplomats. In this climate International PEN in London, with support from leading novelists, poets and foreign literary figures, reached out and requested that writers in Japan form a PEN Club. Japan’s well-known novelist Toson Shimazaki served as the founding president. As suppression of free speech increased as war in the Pacific broke out and the Second World War advanced, Japanese PEN stayed in limited contact with International PEN in London and provided a unique portal to the world for its writers and citizens during that time.

Japan PEN members at PEN’s 71st Congress in Bled: Furukawa Taeko, Miyakawa Keiko and Yonehara Mari, along with Fawzia Assad (Suisse Romand PEN) Huguette de Broqueville (French PEN) and Celia Balcazar (Colombian PEN) and Takeaki Hori (PEN International Board & Japan PEN)

Personally, I remember the hospitality of Japan PEN members who took me out on the Ginza to toast my birthday as I rounded a decade. I had explained that I needed to fly home that evening, a day early to share the birthday. I still remember the glasses of pink champagne flowing up and down the Ginza, (though I was drinking sparkling water), as my own new decade was heralded, then flying halfway around the world and arriving in time to have another dinner that same night with my husband.

Three years later, in September 2010 Japan PEN hosted the 76th PEN International World Congress in Tokyo, one of PEN’s largest with representatives from 90 centers around the theme “The Environment and Literature—What Can Words Do?”

******

World War II, D-Day, the fall of the Berlin Wall—all were global events in the 20th Century which framed the history that followed for much of the world and stirred both despair and optimism among politicians and citizens and inspired stories and poetry among writers. PEN’s Peace Committee conference in March 2007 settled on three themes: Languages under Threat—Dying Cultures, Reading as a Social Event, and Post-Totalitarian Resistance.

Bled, Slovenia, setting of PEN International Peace Committee meeting, March 2007

In my files I found the keynote paper “Post-Totalitarian Resistance” by Peace Committee Chair Edvard Kovač, a portion of which I quote here. It provokes thought with the kind of open-ended questions that don’t necessarily have answers but can lead to discovery. Contents of PEN’s forums are among its important legacy.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall there was a great deal of hope that the era of totalitarian ideologies was over forever. Fukuyama and others even talked about the end of history. But ideological thinking has settled like sediment in people’s minds and it still persistently, albeit imperceptibly, affects our thoughts, conclusions and decisions.

Edvard Kovač, Chair PEN’s International’s Peace Committee, 2007

The role of the writer is to be vigilant and to recognize a transformation in the rigid thinking that until only recently stifled his creativity and pushed him towards dissidence. Perhaps he will notice that the ‘class struggle’ has been transformed and that out of this transformation the germs of new ideologies are emerging: to the legitimate striving for the creation of a Palestinian state a new anti-Semitism has been attached and alongside the right to the existence of the state of Israel the humane protection of civilian population has simply been forgotten. Recognition of and admiration for Third World culture is fortified by anti-Europeanism while a critical attitude to technological civilization confirms the ethno-centrism of the young states. The spread of democracy is confused with domination of the world market and a critical attitude to processes of globalization is interlaced with anti-Americanism. An emphasis on the need for virility conceals a kind of anti-feminism, while the emancipation of women facilitates a new uniformity. The elements of old totalitarianism which have transformed into foundations of new ideologies are harder to unmask as they appear in the name of anti-ideological principles…

…the demise of totalitarianism does not necessarily equate with critical thinking. The defeat of ideologies only creates the possibility of enlightened thinking. In fact, the desire for quick and simple solutions is even greater in post-totalitarian states. Hence the unbearable lightness of new populisms. If in the past it was politics that fully led the economy, it has now come to a complete turnaround so that the economy is stifling political initiative and economic success is putting a noose around the neck of culture and artistic creativity that cannot be marketed…

How can a writer establish a reasonable dialogue when faced with the new fundamentalisms of all colors and creeds?…this new humanism of the pen, which would once again oppose the violence of the sword (which is also the idea behind PEN’s logo) must create new means of expression. So what is the writer’s language in this new struggle?” —Edvard Kovač, Slovene PEN

There are no simple answers to these observations, but the questions continue to be worth asking in PEN’s forums.

Somewhere in the world during most weeks, if not most days, one of PEN’s 150 centers is holding an event or conference and is at work on behalf of writers. For me, the conferences and literary festivals in 2007 included a visit, along with PEN International Executive Director Caroline McCormick to New York to PEN America’s impressive World Voices Festival with over 100 writers from around the globe. The annual World Voices Festival anticipated and informed the launch of PEN International’s own Free the Word! Festival in London in 2008 and in subsequent countries thereafter.

One of the privileges of serving as International Secretary was visiting centers and members around the world though I couldn’t accept all invitations. I regret missing the celebration of PEN’s Global Library launched by members of Slovak PEN. The Global Library gathered books from PEN members worldwide in multiple languages. I missed a conference on freedom of expression and Kurdish literature and a conference in Georgia arranged by Three Seas Writers and Translators’ and the Georgia Writers Union under the auspices of UNESCO, a frequent funder for PEN gatherings. Other International PEN board members and Vice Presidents often did attend as well as the PEN members.

Visit to UNESCO headquarters. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Eugene Schoulgin (PEN International Board Member), Eric Lax (PEN International Board Member), Homero Aridjis (Mexican Ambassador to UNESCO & former PEN International President), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director)

Following the World Voices Festival, Caroline and I, along with International Board members Eugene Schoulgin and Eric Lax, met with UNESCO officials in Paris where former International PEN President Homero Aridjis was now Mexico’s Ambassador to UNESCO. The meetings at UNESCO headquarters and with Homero and the US representative to UNESCO were in anticipation of the renewal of PEN’s formal consultative relationship and “Framework Agreement” with UNESCO. In the prior agreement PEN had also been recognized as a Category II organization with ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council.) These agreements were renewed every six years; the relationship continues to this day.

One country in which PEN and UNESCO were active, but not always with compatible agendas was Turkey. Because UNESCO depended on governments for its funding and PEN frequently criticized the Turkish government for its suppression of free expression, we sometimes walked separate paths in Turkey.

The month after the UNESCO meetings I participated in Istanbul in the Forum on Freedom of Expression, sponsored by that independent organization. Along with dozens of PEN members, I had attended the first Forum on Freedom of Expression in Istanbul in 1997 as Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, and I and other PEN members had spoken at many of the biennial meetings since.

Meeting before Forum on Freedom of Expression in Istanbul. L to R: Novelist Elif Shafak (PEN case at the time), Sara Whyatt (PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Program Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), friend, Journalist Nadire Mater (PEN main case), Eugene Schoulgin (PEN International Board Member)

In Ankara, I was hosted at the International Ankara Short Story Days Festival, an initiative which also aspired to get UNESCO support to establish a World Short Story Day. Professor Aysu Erden, Turkish PEN’s international secretary and editorial board member of PEN International’s Diversity Project of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC) was a champion of the effort. That year the theme was “Preservation of Multiculturalism and Diversity,” a UNESCO focus as well.

Joanne Leedom-Ackerman with Aysu Erden, Turkish PEN board member

In a visit to a large school in Ankara and at a program later that evening, we considered how people and societies bridged differences, how consciousness could change in societies and how literature and stories could play a role. I reflected on the changes during the civil rights movement in the U.S. where I had grown up.

“Many of the stories in my short story collection No Marble Angels are set in the late 1950’s and 60’s in the American South during a time of upheaval in the United States. It was a time when blacks and whites peered at each other over the barriers of history and laws which separated them,” I told both audiences, aware that in Turkey, Kurds often faced discrimination as did Armenians, and the writers who wrote about this discrimination could face time in prison.

That schism is still one of the U.S.’s major national dramas though much distance has been travelled in my lifetime. The abolishment of the laws of segregation and the opening up of opportunity has strengthened U.S. society immeasurably, though there is still a journey to take. It is the closing of the distance between people which has interested me as a writer over the years, whether the distance arises from race or gender or age or simply from the self looking out into the world and seeing an image other than its own.

One of the books that had an impact on me growing up was written by another Texan who literally changed the color of his skin in an attempt to get inside the experience of being black in the South during the time when racial covenants dictated where a person could get a drink of water or sit on the bus or go to the bathroom. John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me came out when I was a school girl. I don’t remember if I read the book then, or a few years later, but when I read it, the dilemma it posed both shaped and mirrored feelings and questions which were growing in me. The questions were really questions of the human condition: Who am I? And who is that person who is not me and different from me?

For a time I considered these as political questions. I spent much of my youth debating issues of civil rights with family and friends. I located the antagonist outside myself, as some monolith, which for lack of a better description had a handle at the top, a wing on the west and several large rivers running through it. And so I left the state of Texas.

As long as the antagonist was outside in politics, society, and culture, I could separate myself from it. As a journalist in the Northeastern part of the United States, I gathered facts and statistics and social opinions and searched for answers to issues. I wrote articles on segregation and desegregation and integration of institutions in the United States. All the while other stories were building in me that I wanted to write, stories that couldn’t so easily be contained in facts and figures and social theory. I began a journey of my own, not by changing the color of my skin, but by considering experience from the inside out. I began writing fiction—short stories and novels. My writing changed from the journalistic to the consideration of the individual heart, from the objective to the subjective.

What continues to interest me in writing are the shadowy places in the individual heart, those places which keep us from seeing one another. Sometimes the distance between self and other is measured in terms of race, sometimes age, sometimes gender, sometimes culture, sometimes religion, sometimes country of origin. I’m interested in the way people go about making bridges or tearing them down.

To the extent a multicultural society recognizes the human spirit that connects its citizens at the same time valuing the cultural differences among them, the society progresses. Multiculturalism is at the heart of International PEN, which has 144 centers in 101 countries. PEN is committed to dispelling race, class and national hatreds in an effort to champion one humanity living in peace; PEN is also committed to freedom of expression.

Because we are writers, literature is our means of expression. Literature has an important role in bridging cultures. The first glimpse we have of another culture is often through reading. We let our imagination take an author’s images, scenes, and characters and bind them to our own lives. We draw from books wisdom and experience.

Many of the characters in my short stories are struggling to expand who they are and come out of themselves, to reach across to another person, to enter and occupy that space at the back of the house, that dark, vine-covered, musty room where “the other” lives. Entering that space, one raises the shades and opens the doors and windows and glimpses in the face of the other, a reflection of one’s self.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 45: Dakar—The Word, the World and Human Values

PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At the end of September 2005 a Danish newspaper published 12 editorial cartoons which depicted Mohammed in various poses as part of a debate over criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark objected, and by early 2006 protests, violent demonstrations and even riots erupted in Muslim areas around the world. The offense was the “blasphemy” of drawing Mohammed in the first place and the particular mockery of some of the depictions in the cartoons.

The uproar over the Jyllands-Posten Mohammed cartoons quickly drew PEN into the controversy, first through Danish PEN and then through the International PEN office and other PEN Centers. PEN included many Muslim members and numbers of centers in majority Muslim countries. All PEN members and centers endorse the ideals stated in the PEN Charter. However, the third and fourth articles of the Charter which addressed the situation, also at times appeared to contradict each other:

Article 3: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

Article 4: “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world toward a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restrain, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

PEN International Board and Staff 2006. L to R: Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Elizabeth Nordgren (Finish PEN), Jane Spender (Programs Director) Sara Whyatt (Writers in Prison Committee Director), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Karen Efford (Programs Officer), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International President), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Britta Junge-Pederson (Treasurer), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair), Chip Rolley (Search Committee Chair), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Peter Firkin (Centers Coordinator) [not pictured: Mohammed Magani (Algerian PEN), Karin Clark (WiPC Chair), Kata Kulavkova ( Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair)

Peace Committee program 2006. Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Veno Taufer (Peace Committee Chair)

At the Peace Committee conference that April, I observed, “The Charter of PEN asserts values that can appear contradictory, but represent the dialectic upon which free societies operate and tolerate competing ideas…In our 85th year, International PEN still represents that longing for a world in which people communicate and respect differences, share culture and literature, and battle ideas but not each other.”

The Danish cartoon controversy led off 2006. For me, the PEN year also included attending the conferences of three of PEN’s four standing committees—the Peace Committee in Bled, Slovenia, Writers in Prison Committee in Istanbul, Turkey (PEN Journey 35) and Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee in Ohrid, Macedonia (PEN Journey 39)—and in May the 72nd PEN World Congress in Berlin, and later a Danish Conference on the Middle East in Copenhagen, the Gothenburg Book Fair in Sweden, a PAN Africa Conference in Dakar, Senegal and a trip to Moscow, where I went to watch my oldest son compete in the European Wrestling Championships and visited Russian PEN on a mission.

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including Alexander Tkachenko, General Secretary, 2006

To Moscow I took just under $10,000 raised by PEN centers and buried in my luggage to help the Russian PEN Center. Vladimir Putin and the Russian government had begun to crackdown on nongovernmental organizations with ties to other countries. One of their first targets was Russian PEN which had opposed the legislation restricting nongovernmental organizations. At the time I was also on the board of Human Rights Watch, a larger organization which was watching closely what was happening to PEN. The government’s attack on Russian PEN came in the form of a freeze on all assets for failure to pay a land tax. Russian PEN argued that it was a legal tenant where it had been conducting business and was not liable for the tax on the land, but the tax office refused to drop the charges. The government threatened to close PEN and take away its office if the money wasn’t paid. An appeal had gone out to PEN’s other centers, which had responded from around the globe not only with protests to Moscow but also with funds for Russian PEN.

I brought in funds just under the amount I would have had to declare. During the wrestling tournament I met with Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko, the General Secretary of Russian PEN, and delivered to him the donation, and he gave me a receipt. The funds stayed off the crisis for then. Charges were dropped. A Russian Minister said, “I don’t understand. I was getting letters from as far away as Argentina!” Sascha answered him: “That is the kind of organization we are.” PEN continued to operate.

In Moscow I also met with Russian PEN members as well as with Turkmen author Rakhim Esenov, who was visiting Russian PEN. I had met Esenov a few weeks before in New York where he had won PEN America’s Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write award. In Turkmenistan Esenov had been charged with “inciting social, national and religious hatred using the mass media” because of characters in his novel The Crowned Wanderer. Set in the 16th century Mogul Empire, the story focused on a poet/philosopher/army general who was said to have saved Turkmenistan from fragmentation. The president of Turkmenistan Saparmurad Niyazov banned the book for portraying the main character as a Shia rather than a Sunni Muslim, and he imprisoned Esenov for several months. I still have the massive Russian language volume he shared with me, a work that had taken him years to write.

L to R: Russian PEN General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko and Russian PEN member outside Russian PEN office in Moscow and Rakhim Esenov, author of The Crowned Wander and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), 2006

At the Peace Committee conference earlier that month I’d presented a paper on the conference theme “The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World,” a broad and challenging topic which had inspired me to peer both backward and forward.

Below is the beginning of that paper with a link to the rest:

My first memory of a PEN meeting was sitting in someone’s living room in Los Angles writing postcards to free Wei Jingsheng from prison in China. At the time in the 1980’s he’d already been in prison several years of a fifteen-year sentence. I had no idea who this writer was thousands of miles away. I barely knew the other writers in that living room. On the coffee table would have been PEN’s Case List, which at the time was white sheets of paper stapled together.

We wrote and stamped our post cards for Wei and other writers that afternoon. I’m sure we were provided with background on his case. I pictured these cards fluttering into a jail somewhere in China and perhaps even into the cell of this stranger to let him know we had taken note of him and cared what happened. Looking back on the blue-sky afternoon as we sipped sodas and ate crackers and cheese, I see our act as a bit fleeting, an effort to imagine the fate of another writer who didn’t have our freedom to write and speak…[continue reading here]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN Journey 39: Spiritus Loci—Literature as Home

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

[From address at Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference September, 2006:]

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

Last year at this conference, I packed in a rush, left behind a pair of shoes, but in the process got a title for a story.

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia.

I don’t yet know what story will emerge, or maybe only this brief talk will emerge, but Macedonia makes the title work, at least to my mind. I Left My Shoes in England…that doesn’t work…I Left My Shoes in France?…No. I Left My Shoes in the United States…please. I look forward to discovering who left the shoes and what the circumstances were and most of all what Macedonia has to do with the story.

Ohrid, Macedonia, setting of PEN International Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee conference, 2006.

Exploring the conference theme spiritus loci will be part of the journey. As writers we know the power of place in literature and in our lives. The Latin term meaning the local spirit of a place is not always easily defined, but it relates to the geography, the history, the architecture and the people, who are both shaped by and shape the place. The ancient Romans thought every location had a spirit, some benign where people would live longer, happier lives and some evil and destructive of human well-being.

Today in a world grown smaller and more connected by jet travel, the internet, the global village, the cyber global village, with the blending of cultures and commerce worldwide, spiritus loci is perhaps a more fluid concept and to a younger generation, even a digital concept. On the internet I discovered a recording studio with the name Spiritus Loci; it moved from place to place recording people’s music wherever the musicians felt most comfortable.

Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) Dimitar Basevski (President Macedonian PEN), and Kata Kulavkova (Macedonian PEN & Chair PEN International’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

It is still the writer who can best capture a place and a people and render that spiritus loci for the reader. The best writers unveil the unity between location and character so that the writer’s version becomes the backdrop for understanding the place for generations to come, whether it be Tolstoy’s Russia, Balzac’s France, Dickens’ England, Achebe’s Nigeria, Toer’s Indonesia, Fuentes’ Mexico.

Through PEN we have the opportunity to know writers and their literature from around the globe and also to visit and experience the places from which they come. I’ve had the pleasure of coming to Macedonia four times and to this most beautiful city of Ohrid because of PEN.

With 144 centers in 101 countries, PEN has members who live and operate in most regions of the globe, with different histories, geographies, races, religions, cultures, but with the common spiritus loci of ideals. Today, these ideals, which were developed between World Wars, continue to promote a shared humanity on earth. PEN members work to use “what influence [we] have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations…to do [our] utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the idea of one humanity living in peace in the world.” This mandate provides its own kind of spiritus loci no matter where one lives. It is a compass that points both to the ground we occupy and the future we hope to achieve.

Meeting at 9th Ohrid Conference of PEN International’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, 2006

Macedonia and its neighbors have been at the center of the struggle for those ideals in the last decade. In 2001 when the fires from the Balkan wars were still smoldering, PEN postponed its International Congress in Ohrid until the conflict in Macedonia subsided. Fortunately we were able to be hosted at a Congress in Ohrid the following fall. When PEN members look at that troubled time in Macedonia only a few years ago and at the current devastating conflicts in the Middle East, it is worth reflecting on how thought evolves, how cultures are translated to each other, and how we can best apply the spiritus loci of our ideals.

When a people find their home destroyed whether by natural disaster or by war, the concept of spiritus loci is problematic. The role of literature is especially important at that time. Literature provides a home in the mind and reveals the humanity we all share—the spiritus loci of the human spirit. Let us not underestimate this power of ideas and writing to transform.

I Left My Shoes in Macedonia. Perhaps the character will return to find the shoes and also to discover what Macedonia might teach. I am at least lucky enough to have returned, and I look forward to seeing what I will learn…wearing my new shoes.

—Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

Next Installment: PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN Journey 36: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part One

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

In pulling out papers from 2005 of PEN conferences and the 71st World Congress, I came across two documents that told a very human story in PEN and a coincidence of life that I share here:

71st PEN World Congress 2005, Bled, Slovenia, Round Table Papers

The first paper I skimmed was a talk I’d given as PEN International Secretary at the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee Conference in Ohrid, Macedonia in September 2005; the paper included the testimony of a PEN member at the end. The second text I read was from the Round Table Papers of the PEN Congress a few months before, in June 2005. This paper was on the Congress theme Tower of Babel: Blessing or a Curse? The paper was the first in that publication and was written by celebrated Nigerian poet Niyi Osundare who speculated on what the world would be should there be just one language and then meditated on what in fact the world was. Shared below are excerpts from Dr. Osundare’s paper, “The Blight and Blessing of Babel:”

“A one-language world would be too simple, too linguistically neat, too unrealistic. And, I daresay, too unnatural. For everywhere in nature there is a tendency towards fission and mutation on an intra-and inter-generic basis. Variety is not only the sauce of life; it is also its source…

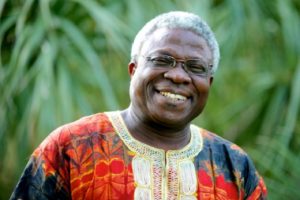

Nigerian poet Dr. Niyi Osundare

“Yoruba culture (the culture in which I was born and raised, and one that I know best) understands the necessity of diversity and inevitability of varieties in different aspects of human life. Hence the saying “Mee l’Oluwa wi” (Many, says the Lord) and “Ona kan o w’oja” (There are countless routes to the same market), both of them short, handy variations on a longer proverb “Oju orun t/egberun eye fo lai farakanra (The sky is wide enough for a thousand birds to fly without colliding). Corroborating this pluralist perspective is the folktale about the Tortoise, ever cunning and self-centered, who one day decided to capture all the wisdom in the world and seal it up in one pot for his own use in an effort to become the wisest being in the world. Of course, his project ended up in a laughable disaster as his pot fell to the ground and exploded while different fragments of the imprisoned wisdom dispersed in different directions, free for all, unmonopolisable. In an essentially pluralist Yoruba worldview, phenomena exist by mutual definition; a thing, a person loses its sense of proportion when there is nothing else to compare it with. The trajectory of life hardly ever follows one straight and narrow path; it must confront the crossroads, experience the thrills and tortures of decision and indecision, before arriving at the juncture of choice. And for the act of choosing to take place, there must be more than one…

“Literature (and the arts generally) is, no doubt, a powerful weapon in the struggle against the blight of Babel. By endowing our airy thought with that ‘little habitation’ and ‘name’ (hail Shakespeare, one of the supreme healers of the wounds of Babel), by generating universal sympathies, globalizing the particular and particularizing the global, by producing that music of the spheres whose winds stir the eaves in different lands, by evoking images which touch hearts across cultures, by articulating those humane values that are essential to human freedom everywhere in the world, by constantly lifting the human spirit and enriching, interrogating human reality with the supple possibilities of fiction…literature strives to restore some of the lost potentialities of Babel. For every significant writer is a bridge-builder of a kind, a witness, a participant-observer, an advocate of a truly humane future.

“No doubt, the phenomenon of Babel has left its fragmentations and dispersals. But it has also bequeathed to humanity a panoply of sounds and letters, an astounding (even if confounding) array of tongues which challenges the tyranny of uniformity and monotony of methods. It has necessitated the building of bridges across diverse tongues and cultures, these bridges being, in a way, a horizontal alternative and antidote to the vertical impossibility of the Tower itself.”

L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary) and Kata Kulavkova (Chair PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

Dr. Niyi Osundare, a Nigerian PEN member, had moved to New Orleans for specialized education for one of his daughters and was also a member of the African Writers Abroad PEN Center. Recounted here is my talk to the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee a few months after the Bled Congress, in September 2005. Only as I recently read the end of my paper did I grasp the connections and the range of PEN’s reach and work. My observations at the time:

The theme of the 8th Ohrid P.E.N. Conference—Writer Within and Without a Homeland—struck a particularly sonorous chord as I was preparing to come here.

In the U.S. the question of homeland has been on the national consciousness for the past month as one of America’s most diverse and multi-lingual cities—New Orleans—has literally disappeared. Its population evacuated as the city sank into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. A large portion of the Gulf coast also fled in the face of Hurricane Katrina. Over a million people dispersed throughout the land in one of the largest displacements in the nation’s history. Many will never return to their homes.

In Europe and Africa, Asia and Latin America even larger displacements have occurred in the last century, often because of war, famine, politics, and also weather. All of us remember the disappearance of towns and villages and whole sections of coasts in the countries hit by the tsunami last December.

When a home is suddenly gone, family scattered, livelihood and career and ambitions all uprooted, one is forced to consider what endures, and what one can take with him. Home moves from a physical place to a place in consciousness.

The ability to speak with others and to tell the story is especially important and makes the idea of language as homeland compelling, also imagination as homeland, literature and art as homeland, and particularly relevant to PEN, a community of fellowship as homeland.

I’d like to read a message to PEN’s Africa Writers Abroad Centre from a Nigerian writer trapped in New Orleans:

This is my first real internet access since the disaster struck…I can’t thank you enough for your concern and care. It’s been all so overwhelming. My wife and I are alive and, after passing through five horrendous “evacuation centers”, have been allocated to the Red Cross shelter in Birmingham, Alabama. The nightmare of the past seven days is simply unimaginable. We very narrowly escaped drowning in our own house. Pursued by an 8-foot high toxic flood water (15 feet in the street outside our door), we were forced up a stuffy, airless attic, where we were holed up for 26 hours, with no food, no water, no prospect of any rescue. We were only saved by the fortuitous intervention of a neighbor who heard our shout for help when he came round with his rescue boat to pick up something from his own house. With life vests provided by him, we managed to swim out of our house, leaving everything we had behind. Right now, all our clothes, books, academic and professional credentials, travel documents, computers, manuscripts, etc are submerged in the dirty waters of the New Orleans flood. Hell has no other name… We deeply appreciate your concern. Kindly pass on our gratitude to all on your list serve.

Yours in the Eye of the Storm

[Niyi Osundare]

I’m told he has been overwhelmed by the outpouring of concern. While the concern and offers of assistance can’t replace what was lost, it can fill in some of the spaces in the heart.

In the U.S. those displaced are at least relocated in the same country and for the most part speak the same language, though the difference in accents has its challenges. What has been heartening has not been the help of government agencies, but the outpouring of citizens in communities all over the nation and abroad. One would wish this empathy would prevail and continue.

The ability to imagine and to reach out to another and try to see from the other’s point of view is one of the elements of great literature and also of great people. This empathy is a value around which PEN has developed and one which PEN at its best embodies.

A community spread across 99 countries, shaped by different nationalities, cultures, races, religions, and languages, PEN is a fellowship of writers who appreciate the importance of telling a story and defend the writer’s freedom to tell it as he sees it and to tell it in the language of his choosing. Language is the writer’s tool, expressing the music of his thoughts and sounding the chords of his imagination.

Language, imagination and fellowship—all are a kind of homeland that can survive the elements and can even survive politics and war, a homeland, one of whose addresses we like to think is at P.E.N.

Dr. Osundare and I didn’t know each other at the time though perhaps met briefly at the Bled Congress which was attended by more than 275 writers. I know many of his colleagues from Nigerian PEN and at the time from the African Writers Abroad PEN. I made the connection only as I reviewed the papers. Dr. Osundare is now a professor at the University of New Orleans.

Delegates at PEN International World Congress, Bled, Slovenia, June, 2005. L to R: Remi Raj (PEN Nigeria), Dan Kayhana (PEN Uganda), Frankie Asare Donkoh (PEN Ghana), Alfred Msadala (PEN Malawi)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

PEN Journey 34: Diyarbakir and Beyond—Finding Byways for Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN has always been about building bridges, finding the byways of fellowship among writers whose currency is language and imagination and whose hope is that even with radically different histories and backgrounds, writers might find a way to sit down across a table from each other and share stories and listen to each other and thereby have a beneficent influence on the way they and their societies see themselves and others.

It is an idealistic goal that has been battered in PEN’s hundred year history, and yet the organization continues; the dialogues continue, and writers from over 100 countries continue to meet and talk, even from countries whose governments have not found peace in decades. There have been moments of seeing that optimism realized, at least for a time, and also seeing it smashed.

The next section of these PEN Journeys covering the years 2004 (PEN Journey 33) through 2007 (August) will focus on my years as International Secretary of PEN International. I will travel through events chronologically, the number of events increasing considerably as the role demanded. I will try to knit these together as we continually try to do as an organization.

International PEN Seminar on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

In January, 2005 we held our first board meeting of the year in Vienna where PEN President Jiří Gruša had recently taken up the position as Director of the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna which hosted us. The formal board meeting itself took place in the basement of the hotel restaurant where we were staying. Around the table in the cozy space where we sat on chairs and on a long booth was PEN’s diverse board from Algeria, Colombia, France, USA, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Croatia, Australia, Norway and Japan. The search for an executive director, the new financial and employment systems going into place in the office, an upcoming meeting in Stavanger, Norway with the old Cities of Asylum Network, and an upcoming meeting in Diyarbakir, Turkey with Kurdish and Turkish PEN—all populated the agenda as did the omnipresent discussions on fundraising.

For me, the imminent departure of my Marine son from the combat zone in Iraq hovered in the corner of my mind. We were staying at a pension hotel with small rooms—single bed, dresser and nightstand; I could almost touch the walls on both sides. Outside it was snowing. I’d come to Vienna unprepared for the snow and had bought at a sale a large puffy yellow coat that now draped across the bed for warmth. At night in the dark as I fell asleep, I thought about my son and one night dreamed a desperate dream. Then the phone rang; it was 1:30 in the morning. My husband’s voice woke me. “Wheels are up!” he declared. “They are on their way home!” I still remember the moment, lying there in the dark, snow glistening in the light through the small window and feeling as though the walls had suddenly expanded and a weight lifted that I hadn’t been fully aware I was carrying. The memory…the snow, the Cathedral we passed each day in the square and at dusk in the evening, the puffy yellow coat…

I was wearing that same coat as snow fell later that month in Washington, DC the day my son finally pulled into our driveway. I was sitting on the front porch swing in the snow waiting for him, thinking about the hotel room in the dark, the restaurant basement where we helped craft a conference for writers from the hostile parties in Turkey and another to find sanctuary for writers fleeing oppression—all these memories are wrapped together in a moment of return and of the spirit lifting and life opening a corridor to walk down.

Czech PEN 80th Anniversary in Louvre Cafe where PEN members met in 1925. L to R: Playwright Tom Stoppard, PEN Int’l President Jiří Gruša, Czech PEN President Jiří Stránský.

The next meeting I attended that winter on February 15, 2005 celebrated the 80-year anniversary of Czech PEN. In Prague Jiří and I toasted the endurance of his PEN Center which had been founded by Karel Čapek and 37 Czech writers on that day in 1925. Czech PEN had survived the Second World War, the Cold War, the Soviet occupation and finally the liberation. Former prisoner, playwright and PEN member Václav Havel had become President of the country and his good friend and also prisoner Jiří Gruša was now President of International PEN. Under the auspices of the Minister of Culture, we met with Havel and playwright Tom Stoppard, himself Czech, and Jiří Stránský, President of Czech PEN at the Louvre Café where the original PEN gathering had taken place. Later, the Mayor of Prague hosted a reception with Czech PEN members in the Old Town Hall where he opened an exhibition celebrating “Eighty Years of the Czech PEN Club.”

The following week Writers in Prison Director (WIPC) Sara Whyatt and I traveled to the city of Stavanger, Norway which sat on the sea with a harbor and ships at dock. The Stavanger meeting brought together PEN and members of the now disbanded International Parliament of Writers, an organization founded after the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. The Parliament of Writers had developed a program to house writers in cities of asylum, but the Parliament of Writers no longer functioned. Many of the cities, however, still wanted to continue their hospitality for writers at risk. Stavanger itself hosted writers, including poet and novelist Chenjerai Hove, who’d been president of Zimbabwe PEN until he’d had to flee the government of Robert Mugabe. Hove was a fellow at the House of Culture in Stavanger until he passed away in 2015.

Stavanger, Norway, February, 2005 setting for birth of International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN)

Helge Lunde, director of the Stavanger International Festival of Literature and Freedom of Speech convened PEN, representatives from the old Parliament of Writers and representatives from some of the cities that wanted to continue the program. In a several day meeting, the outlines of what would become the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) were laid down with PEN as the vetting organization for applications and also a source of hospitality when writers arrived in their new temporary homes. ICORN remains active today in partnership with PEN in over 70 cities which promote and protect freedom of expression and host writers and artists at risk by providing housing, an income, literary arenas, scholarships and grants. PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee and ICORN regularly hold biennial meetings together.

Writer Liu Binyan, a founder and first President, Independent Chinese PEN Center

The following weekend at Princeton University the relatively new Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), founded in 2001, honored Liu Binyan, one of its founders and first President. ICPC’s members live both in China and abroad. The PEN Center gave them the ability to talk with each other and hold programs together, often in Hong Kong. Because of his writing and criticism of the Chinese Communist Party, especially after Tiananmen Square, Liu Binyan had not been allowed to return to China after an academic stay in the U.S. Though he never saw China again, in the U.S. he wrote and worked as Director of Princeton University’s China Initiative. (Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo was also a founder of ICPC and its second president.) At the dinner at the Princeton Faculty Club, ICPC members and China scholars presented Liu Binyan the book Living in Exile, written by distinguished essayists in China and abroad and dedicated to Liu who had spent considerable time in detention and in and out of labor camps. Later that year Liu Binyan passed away at his home in New Jersey.

In March “The International PEN Diyarbakir Seminar on Cultural Diversity” convened the largest and most ambitious conference that quarter in the primarily Kurdish southeast of Turkey. For years the Writers in Prison Committee had focused on cases in this dangerous region where fighting between the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and the Turkish military had resulted in multiple imprisonments and killings. However, a rapprochement appeared to be expanding between the government and Kurdish citizens. In this space, PEN International had been working with Kurdish PEN and Turkish PEN to prepare this historic meeting of the two centers, along with PEN’s leadership of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC). For the first time Kurdish writers and Turkish writers would speak side by side from the same stage in Kurdish and Turkish with translations of each language.

Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jane Spender (PEN International Program Director), Carles Torner (Vice Chair Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee).

My predecessor as International Secretary Terry Carlbom had been instrumental in the planning, and we all agreed he should continue as coordinator of the seminar. Seventy delegates from a dozen countries gathered in the ancient city of Diyarbakir/Ahmed for five days. Diyarbakir dated back at least 5000 years, one of the oldest cities in the ancient land of Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Later it was dominated by Persia and by Alexander the Great. Because of its strategic position, Diyarbakir’s sovereignty changed many times, was part of the Roman empire, later conquered by the Arabs in 639, by Tamerlane in 1394; the Ottomans conquered in 1515. Diyarbakir continued through cycles of battles for control.

Old Diyarbakir was a standard Roman town circled by a wall, the stones of which still stood. The black basalt wall was said to be second only to the Great Wall of China. Within the walls a labyrinth of cobbled streets and alleyways unfolded, leading to towers where we could see the rivers and gardens and the city’s mosques and street life below, where caravan travelers used to stop on the silk road.

Before the conference began, PEN International Program Director Jane Spender and I explored the twisting paths and shared black tea in a central plaza with Carles Torner, vice chair of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee. As an American whose national history extended back barely 400 years, this accumulation of history in the streets and walls and buildings was mind-bending. In stones, in ideas…where did history reside and how did it evolve?

On the first evening Diyarbakir’s Lord Mayor Osman Baydemir greeted us at the Town Hall for a Newroz (New Year’s) reception. I thanked him on behalf of PEN for all he and the city had done to support this seminar. “It is a treat for us to visit one of the world’s oldest cities, with a history that could occupy the imagination of a community of writers like us for years to come,” I said. “Central to the Charter and ethos of PEN is a celebration of the universal which binds us as human beings and of the diversity which distinguishes each individual—the specific history, language and culture. It is our challenge and our aspiration as writers and members of PEN to provide the forums where cultures don’t clash but communicate. That is what we hope to do here in Diyarbakir.”

The first full day of the seminar we spent at the Newroz Festival. Our delegation was seated in an honored place in the bleachers which turned out to be behind the mother of Abdullah Öcalan, one of the founders and leaders of the PKK who was currently in prison. On the grounds in front of us spread thousands/ hundreds of thousands—some said a million people—celebrating the Kurdish new year, a time that coincides with the March equinox. Terry Carlbom and I were soon escorted to the main stage where we stood looking out over a sea of people as far as we could see, many in colorful local dress. Because PEN is specifically a nonpartisan/nonpolitical organization, we felt some ambivalence at the appearance of being swept into the Kurdish cause; on the other hand, the experience was one I won’t forget. The day was celebratory without violence. If there were political speeches, they were not translated for us, and we were accompanied by our Turkish colleagues who also attended.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference on Cultural Diversity, 2005. L to R: Mehmed Uzun and Dr. Zaradachet Hajo (Kurdish PEN), Kata Kulavkova, (Chair, PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), and Üstün Akmen, Turkish PEN

That evening in opening the conference, I noted, “In Diyarbakir/Ahmed this week we’ve come together to celebrate cultural diversity and explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.”

The official program began with the Lord Mayor and the President of Kurdish PEN Dr. Zaradachet Hajo and the President of Turkish PEN Mr. Üstün Akmen and a keynote speech by Kurdish author Mehmed Uzun. The following evening Turkish writer Murathan Mungan delivered an introductory address to a public gathering.

At the conference itself Kurdish and Turkish writers, poets, publishers and translators shared history and literature across their linguistic borders. Through discussion and readings and performances, they addressed the importance of cultural diversity as a value in a culture of peace.

Renowned Turkish/Kurdish novelist Yaşar Kemal, former president of Turkish PEN, had been invited but was ill and sent a message instead. He noted that the world was going through a difficult period and was faced with terrible destruction. He asked, “What makes human beings? Love, compassion, peace, friendship…Human beings are the only creative beings in the world.” Local cultures are being destroyed and with that is the destruction of languages and art and values, he said. In life and death we have to stand against a terrible destructive force in favor of local and national culture. “I believe your meeting will be successful,” he predicted.

Kata Kulavkova, Chair of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee emphasized the importance of the capacity to imagine, the importance of cultural memory and openness to dialogue. “Europe needs all identities, including Kurdish identities,” she said, noting that every culture is the center of the world for itself. “Turkish and Kurdish culture depend on each other to promote Turkish/Kurdish universal culture.”

Hüseyin Dozen of Kurdish PEN noted that literary translation helps a language to flourish; languages that are not standardized are enriched by literary translation which is an art rather than a scientific discipline. As far as languages that have no official status or have been prohibited, oral literature plays a central role, and the work of a translator must not neglect this kind of literature in his work.

PEN Vice President Lucina Kathmann led a discussion on “Bridging Borders” among women writers. Müge Sökmen of Turkish PEN moderated a discussion on Diversity and Literary Translation; Kurdish PEN member Berivan Dosky moderated a discussion on Cultural Diversity and Peace; Turkish PEN’s Vecdi Sayar led the discussion on Cultural Diversity and Dialogue, and Aysu Erden of Turkish PEN moderated a panel on Cultural Diversity and Linguistic Diversity.

PEN trip to ancient town of Hasenkeyf, Turkey, 2005 including PEN International and Turkish and Kurdish members