Posts Tagged ‘PEN Writers in Prison Committee’

PEN Journey 9: The Fraught Roads of Literature

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

Twelve-foot puppets danced outside the dining room’s second floor windows at our hotel, billed as the “oldest hotel in the world,” set on the central plaza of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, the venue for PEN International’s 60th Congress.

Sara Whyatt, coordinator of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, and I hurried to finish breakfast and our agenda before we joined the crowds outside at the historic Festival of St. James. That evening International PEN’s 60th Congress would convene. Hosted by Galician PEN, the Congress had as its theme Roads of Literature, which seemed appropriate as pilgrims from around the world also gathered on the Obradoiro Plaza in front of the ancient Cathedral, the destination for their Camino.

Parador Hotel, Santiago de Compostela St. James Festival, Obradoiro Plaza, Santiago de Compostela

At this Congress the presidency of PEN was changing hands as was the chairmanship of the Writers in Prison Committee, which I was taking over from Thomas von Vegesack. Ronald Harwood, the British playwright, was assuming the PEN presidency from Hungarian novelist and essayist György Konrád, who had been a philosophical president, often running the Assembly meetings like a stream of consciousness event where the agenda was a guide but not necessarily a governing map. Ronnie ran the final meeting like a director and dramatist, determined to get the gathering from here to there with a path and deadline. Both smart, experienced writers, committed to PEN’s principles, they had very different styles. Known only to a few of the delegates a surprise visitor was also arriving mid-Congress.

The 60th Congress in September 1993 was a watershed of sorts. It was the first since the controversial Dubrovnik gathering six months before which had split PEN’s membership (see PEN Journey 8) because of the war in the Balkans.

Konrád’s opening speech to the Assembly explained that PEN’s leadership had gone ahead with the congress over the many objections from PEN centers because the venue had been approved earlier by the Assembly and the host center had been unwilling to postpone. He acknowledged the widespread criticism and also the concern that some individuals who fomented the Balkan wars and participated in alleged war crimes were writers who had been members of PEN. He said, “That these men of war also include men of letters, indeed that these latter are well represented, painfully confronts our professional community with the notion of our responsibility for the power of the Word. Nationalist rhetoric led to mass graves here, and there. Mutual killings would not have been on such a scale in the absence of words that called on others to fight or that justified the war.”

György Konrád, PEN International President 1990-1993, Credit: Gezett/ullstein bild, via Getty Images

Konrád’s address at the opening session went a way in bringing the delegates together. “What we can do is to try and ensure the survival of the spirit of dialogue between the writers of the communities that now confront each other….International PEN stands for universalism and individualism, an insistence on a conversation between literatures that rises above differences of race, nation, creed or class, for that lack of prejudice which allows writers to read writers without identifying them with a community…

“Ours is an optimistic hypothesis: we believe that we can understand each other and that we can come to an understanding in many respects. The existence of communication between nations, and the operation of International PEN confirm this hypothesis…PEN defends the freedom of writers all over the world, that is its essence.”

Ronald Harwood added in his acceptance for the presidency: “The world seems to be fragmenting; PEN must never fragment. We have to do what we can do for our fellow-writers and for literature as a united body; otherwise we perish. And our differences are our strength: our different languages, cultures and literatures are our strength. Nothing gives me more pride than to be part of this organization when I come to a Congress and see the diversity of human beings here and know that we all have at least one thing in common. We write…We are not the United Nations…We cannot solve the world’s problems…Each time we go beyond our remit, which is literature and language and the freedom of expression of writers, we diminish our integrity and damage our credibility…We don’t’ represent governments; we represent ourselves and our Centres…We are here to serve writers and writing and literature, and that is enough…And let us remember and take pleasure in this: that when the words International PEN are uttered they become synonymous with the freedom from fear.”

Ronald Harwood, PEN International President 1993-1997. Credit BAFTA

PEN’s work to defend writers and protect space free from fear fell in large part to the Writers in Prison Committee, the largest of PEN’s standing committees with over half the PEN centers operating their own WiP Committees. Members elected the writers who were in prison for their writing as honorary members of their centers, corresponded with them and their families, advocated on their behalf with their own governments and with the governments where the writers lived. PEN’s London office provided the research, selected the cases, planned campaigns and worked with international bodies. The means and methods have modified over the years as the internet and social media have developed, but the focus has remained on the individual writer whose case is pursued until it is resolved. With consultative status at the United Nations, International PEN and its Writers in Prison Committee work through the Human Rights Commission and UNESCO and with other international institutions lobbying on behalf of writers.

At the time of the 60th Congress focus of WiPC’s work included China, Turkey, Algeria, Burma, Syria and Nigeria. In Turkey that summer an arson attack at an arts festival in Sivas had killed at least 37 people, seven writers and poets. One of the writers at the festival Aziz Nesin was translating Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses into Turkish and had started to serialize the book in a newspaper. Nesin’s presence at the festival was said to inflame the local crowds. Though Nesin survived, it was reported he was beaten by the firefighters who saved him, and a subsequent investigation held the Turkish state responsible. China continued to have more WiPC cases than any country except Turkey. The threat of death for writers had intensified in Algeria where Islamic extremists had assassinated six writers, including the novelist and journalist Tahar Djaout. In Nigeria the brief imprisonment and possible sedition charges against writer Ken Saro Wiwa, President of the Nigerian Association of Authors, founding member of Nigerian PEN and leader of the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People was highlighted after his passport was confiscated. A few years later his situation would inspire a global mobilization by PEN and human rights groups after Saro Wiwa was condemned to death by Nigeria’s de facto President Sani Abacha.

The focus of the 60th Congress remained on the Balkans and on growing religious extremism. PEN’s surprise guest appeared at the Assembly in the middle of the Peace Committee report on the Balkans. That morning delegates had entered through a metal detector and security check, the first and only time in my years at PEN. The day before, the guest was to have slipped into the hotel secretly because of security concerns, but the plaza outside was filled with people who had come to see the arrival not of Salman Rushdie but of singer Julio Iglesias who arrived at the same time. Rushdie was quickly whisked inside. That evening a small group gathered for dinner with Rushdie in a private dining room at the hotel. I remember sitting beside Salman and sharing a dessert with him but have no notes from the dinner and remember only a discussion of PEN’s further campaign on his behalf. At the time the fatwa weighed heavily. Translators and publishers of Rushdie had been killed and attacked.

The next morning Rushdie arrived in the hall during the Peace Committee’s report which took a break for Rushdie’s address. The Assembly passed a resolution again condemning the fatwa and urging Iran to rescind it and urging all PEN Centers to continue lobbying their governments on Rushdie’s behalf and to put the case on the agenda of the International Court of Justice and other multilateral fora.

International PEN 60th Congress Assembly of Delegates in Santiago de Compostella 1993. Left to right: György Konrád, Salman Rushdie, Ronald Harwood

To the Assembly Rushdie noted: “…in the Muslim world, in the Arab world when journalists and academics and other visitors ask writers, intellectuals, and other dissident figures in those countries what they think, they repeatedly say: ‘The reason you must defend Rushdie is that by doing so you defend us also.’ For example, Iranian dissident intellectuals, 167 of whom recently signed a very passionate declaration in support of me and of the principles involved in this case, say that the real target of the Khomeini Fatwa and of Iranian state terrorism is not Rushdie, it is them.’ After all I have protection; they don’t. And what the terror campaign means is ‘If we can do this to Rushdie, think how much we can do to you.’”

He said, “There is something I wanted to say about the issue of fear. I do think that a lot of people who mean well and wish to combat this kind of attack are silenced by fear, and think that by remaining silent, somehow things will get better…But the one thing that I’ve learned is that silence is always the biggest mistake, always no matter how great the temptation to silence might be, for a very simple reason. If you are silent, you allow your enemy to speak, and therefore you allow him to set the terms of the debate…I think one of the reasons I’m here is that all of you, and thousands of people around the world have not remained silent.”

Rushdie thanked PEN for its work on his behalf. When asked how this situation affected his writing, he said he’d actually become more optimistic. “I was determined to construct a happy ending and discovered it is very difficult. Happy endings in literature as in life are very difficult to arrange…[but] the answer is that it’s made my writing much more cheerful.”

Rushdie stayed after his address and participated in the discussion on the Balkans. Miloš Mikeln, chair of the Peace Committee, reported that besides help provided to writer refugees and those staying in Sarajevo, the Peace Committee was closely following and analyzing the situation in the war regions, focusing on writers’ involvement in instigating chauvinistic hatred and war propaganda. The most drastic case was that of the Serbian poet from Bosnia, Mr. Radovan Karadzic, who was now the President of the self-proclaimed Serbian Republic of Bosnia. The Peace Committee report noted that he’d used his literary talent and his reputation as a writer to foster ethnic and religious hatred and to promote genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina. “As writers who deeply believe in freedom of expression we cannot remain silent in the face of such an abuse of the freedom,” Mikeln said. “We find it incumbent upon us to condemn Radovan Karadzic for his violation of all the values that we and International PEN stand for.”

After lengthy debate on whether to name names in resolutions, this condemnation was accepted and taken as a statement of the Writers for Peace Committee. Personal condemnation is highly unusual for PEN, used most notably in the expulsion of Nazi writers in 1933. The debate further focused on the responsibility of PEN members, in particular Serbian PEN members and the Serbian center. It is also very unusual for the PEN Assembly to publicly call out a center. The resolution noted, “Writers in Serbia actively supported chauvinistic propaganda, misusing their influence as writers and thus instigating hatred, destruction and war. These actions including public statements by ___ and _____clearly run against the principles of International PEN. The 60th World Congress…condemns such a blatant abuse of our profession. We expect the Serbian PEN to take a stand against this breach of writers’ ethics as we would expect of any Center confronted by a similar situation.” In this instance the names were included in the original resolution but after debate were left out of the resolution passed by the Assembly.

The Bosnian delegate made a passionate plea protesting what was happening in Bosnia and the characterization of the situation as “civil war” by others. Rushdie said that the delegate from Bosnia was justified and should be heard. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the situation, there was no question that the crimes committed against Bosnia had been the greatest and Sarajevo the most tragic case, Rushdie said, and he hoped the delegate was wrong when he said people outside did not care and did not want to know. The destruction of Sarajevo would haunt Europe for generations, and he added that the people who had wanted to maintain a unified society had been sacrificed, and it was hard not to believe that it was because they were Muslims. Suppose the Serbs had been Muslims. The Bosnian culture was the culture of Europe.

The Assembly of Delegates approved the Peace Committee’s resolution with names removed and also endorsed a recommendation by Russian PEN that was to be annexed to the resolution. That statement declared that PEN “expresses its firm conviction that the duty of writers, and particularly of the writers of those ethnic groups and countries which are directly involved in the armed conflicts is not to espouse national interests but, in the cause of the unity of the world, promote negotiation and compromise so as to obtain the solution of all conflicts.”

PEN Congresses are full of speeches and resolutions, words offered in a world buffeted by much harder power, but PEN members have faith that words matter and can have power for good or ill, that there is a difference between words that aim for truth and words that are used for propaganda. At that time and in times before and since, words have inspired peace but also inflamed towards war. PEN remains a place where words and actions come together in campaigns to preserve the freedom of writers to use their words.

At the 60th PEN Congress in the grand ballroom of the oldest hotel in the world a new Bosnian Center whose members were Serb, Croat and Bosnian was unanimously welcomed as was an ex-Yugoslav Center for writers who no longer lived in the region.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 10: WiPC: Beware of Principles

PEN Journey 7: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Iraq invaded Kuwait August 2, 1990. When I picked up my 10-year old son from camp in the U.S. that summer and told him what had happened, his first response was: What about Talal and Alec? These were two of his good friends at the American School in London—one was son of the Kuwaiti Ambassador; the other was from Iraq. He quickly understood the consequences. Fortunately, both of his friends had been out of their countries at the time, though I don’t recall Alec returning to the American School that fall. When the bombs dropped on Baghdad in January, the American School went into lockdown. The older students were issued identity cards. The security force around the school multiplied. When Talal came over to play that winter, he was accompanied by two imposing body guards who stayed outside.

Though the fighting in Iraq concluded by the end of February, security in London continued. By the end of March, the war in the Balkans had begun. Both wars brought to a close the honeymoon many felt after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For PEN, the outbreak of war in Iraq and in the Balkans led to the cancellation of the planned Delphi Congress and to the convening of conferences in Europe and a two-day gathering of PEN’s Assembly of Delegates and international committees in Paris in April 1991. Delegates from 39 PEN centers came together to conduct the business of PEN at the Société des Gens de Lettres de France which occupied the 18th-century neoclassical Hôtel de Massa on rue de Faubourg-Saint-Jacques in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. There were no literary sessions or social gatherings, or the usual simultaneous translation of proceedings. The business was conducted primarily in English with intermittent French, the two official languages of PEN. (Spanish was added a few years later as PEN’s third official language.)

The Gulf War, the ethnic conflict in the Balkans, the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square trials and the ongoing fatwa against Salman Rushdie predominated discussions in Paris and later in November at the 56th PEN Congress in Vienna. The Gulf War had resulted in increased numbers of writers imprisoned and killed in the Middle East and an increase in censorship. Resolutions condemning the detention and imprisonment of writers in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Israel and Turkey passed the Paris Assembly. Little information was available from Iraq. Another resolution in Paris sponsored by the two American centers expressed concern to the U.S. government and all U.N. member states over the restrictions placed on journalists during the war and urged a review of the ground rules for journalists in conflicts.

Turkey and China continued to hold the largest number of writers in prison, as has been the case for most of my 30-year involvement with PEN. At the time the Turkish government had announced an amnesty for approximately a third of the writers, and there was some hope they might release the additional 80, but new laws were also proposed that could be used against writers. In China where 87 cases were reported, the authorities had announced the end of investigations on the leaders of the June 1989 Democracy Movement. Most sentences were lighter than expected with credit given to human rights organizations like PEN who had kept up pressure.

However, this was not the case for Wang Juntao, a 32-year old academic and Deputy Editor of the Economics Weekly newspaper. In a letter to his lawyer published at the time in The South China Morning Post Wang Juntao explained why he had spoken as he had at the trial even though he knew his penalty would be more severe. “…Only by so doing can the dead rest in peace, since on the soil where they shed blood there are still some compatriots who take risks and speak out from a sense of justice in the most difficult circumstances…” His lawyers had been given just four days to prepare his defense. He was sentenced to 13 years in prison with four years subsequent deprivation of political rights for the crime of conspiracy to subvert the government and for carrying out counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement. His lawyers pressed him not to appeal so his wife had to do so and was given only three days. The appeal was rejected. [In 1994 Wang Juntao was one of the prisoners the U.S. demanded be released as a condition for trade talks. He was released from prison for medical reasons and now lives in exile in the United States where he has studied and received advanced degrees from Harvard University and a PhD from Columbia University. PEN was among the organizations which lobbied for this release.]

PEN International’s case sheet for Wang Juntao sent by fax and mail in 1990 to centers and members. In 1991 PEN International launched a Rapid Action Network to notify centers and to summarize the cases, actions and advocacy.

During this period PEN through its partnership with UNESCO convened writers in the Middle East and also writers in the Balkans to find common ground and to search out the pylons upon which bridges might be built and to monitor the situation for the writers in the regions. However, because of the Balkan War, it wasn’t possible to hold the meeting with the Yugoslav Centers in Bled as the Slovene Center had proposed. Instead PEN International President György Konrád hosted the gathering in Budapest and followed up with a meeting of South-Eastern European centers in Ohrid, hosted by Macedonian PEN though the Croatian Center wasn’t able to attend. The discussion included the desirability of recognizing the right of conscious objection in time of civil war and the possibility of solving the problem of minorities by allowing multiple citizenship.

Summary statement of the August, 1991 Conference on the Balkans with all centers from the former Yugoslavia attending except the Bosnian Center, which didn’t come into being until the following year.

In addition to convening dialogues among writers and lobbying on behalf of threatened writers during the Balkan conflicts, PEN also provided financial assistance. Boris Novak, the Slovene Chair of PEN’s Peace Committee and President of Slovene PEN took many precarious trips into war-torn Sarajevo during the almost four-year siege of the city. At one point he reported at least 52 writers and their families were trapped and could only leave if invited to an international peace conference. Slovene PEN planned to host such a conference and invite the writers and their families with the hope the U.N. Peacekeeping Force could provide protection for their exit. He urged other PEN centers to assist in finding residences and perhaps temporary teaching appointments or fellowships for these writers. He also delivered aid to trapped writers, aid gathered from other PEN Centers, donated to the Writers in Prison Committee Aid Fund and to PEN’s Emergency Fund run out of Amsterdam with Dutch PEN.

In an intersection of conflicts, the German and Finnish publishers of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses donated their proceeds from the book to PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. By the Vienna Congress, Rushdie had lived 1000 days under death threat. PEN continued its defense of Rushdie and its protest against the accompanying violence of the fatwa. The Japanese translator of Satanic Verses had been killed, and the Italian translator badly beaten. (Two years later the Norwegian publisher was shot three times and left for dead.) The bounty had increased on Rushdie, and there was allegedly a hit squad deployed in Western Europe to assassinate him.

One of many letters sent by International PEN to support Salman Rushdie and to protest the ongoing fatwa.

My personal engagement and memories during this period focused on work with the Writers in Prison Committee and to a lesser extent with the formation of the Women’s Committee, which I supported but which others were driving, and with the establishment of the International PEN Foundation which would be able to receive tax exempt funds for many of these PEN activities. After a discussion of the Foundation’s framework at the Paris Conference, including assurances that the Foundation would not interfere or challenge PEN’s governance, I presented the formal proposal at the Vienna Congress where the Assembly of Delegates approved the establishment of an International PEN Foundation. The Foundation received official charitable status in March 1992 and operated for the next decade until British charitable tax laws changed and a separate foundation was no longer necessary.

Also at the Vienna Congress the Women’s Network, which had formed at the Canadian Congress in 1989, gained approval as a standing committee of International PEN with assurances that men and women were welcome and would work together. Meredith Tax, a chief strategist and one of the founders, explained the committee would involve more women in the work of PEN at all levels and address problems that particularly affected women writers in developing countries and would enable women to know each other’s work, much of which was not translated. “The Women’s Committee will be a force to strengthen, not weaken PEN,” she assured the Assembly.

The eventual governance of the Women’s Committee included PEN members from around the world and its chair rotated to different regions. Each of PEN’s standing committees had its own governing structure. The Women’s Committee was unique in its inclusiveness, which had its own challenges, but which foreshadowed a more inclusive governing structure for PEN International. Twenty-eight PEN centers signed up for the committee with 70 delegates and members, including men, attending the initial meeting.

L to R: Moniika van Paemel, (Belgium Dutch-speaking PEN) and Meredith Tax (American PEN) at Women’s Committee Planning meeting at Canadian Congress, 1989

At the time International PEN’s leadership was all male. In its 80-year history International PEN had never had a woman President and only one woman International Secretary and few women as Committee chairs though in many centers of PEN there was a growing balance of men and women members and leaders. In 2015 novelist and poet Jennifer Clement was elected the first woman President of International PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 8: Thresholds of Change…Passing the Torch

PEN Journey 6: Freedom and Beyond…War on the Horizon

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey is of some interest.

PEN members played key roles in the shifting landscape of Europe in the early 1990’s as the Berlin Wall fell, and the East moved closer to the West. Playwright and PEN member Vaclav Havel, who spent multiple stays in prison for his opposition and activism against the Communist regime, was elected President of Czechoslovakia in December, 1989. Czech writers Jiri Stransky and Jiri Grusa, both of whom spent time in jail under the Communists, later worked with Havel. Jiri Stransky became President of Czech PEN, and Jiri Grusa worked in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and later was elected President of PEN International in 2003. Dissident Hungarian writer Arpad Goncz, whose name was on the program of the 55th PEN Congress as a member of the Hungarian delegation, was prevented from coming because on the day he was to depart, he was elected President of Hungary.

Czech PEN members playwright Tom Stoppard, Jiri Grusa (President of PEN International) and Jiri Stransky (Czech PEN President) at historic restaurant in Prague in 2005

At PEN’s 55th Congress in Madeira, Portugal May,1990, Hungarian novelist Gyorgy Konrad was elected President of International PEN after the unexpected death of President Rene Tavernier. According to the interim and past President Per Wastberg, Konrad had been “very active in the spiritual liberation not only of his own country, Hungary, but of Eastern and Central Europe.”

Konrad told the Assembly of Delegates, “It had been the spirit of human rights, which corresponded with the main interest of the freedom of the mind and of literature, which had been the motive force in recent events in Eastern Europe so that it had been the spirit, rather the physical force, which had caused the shifts in power.” [But] “liberated from the uneasy situation of the censorship of the one-party system, writers there were facing a new sort of danger, the danger of conflicts between nationalities spurred on by national chauvinism. If it was possible to find understanding between writers in that very disturbed part of Europe, maybe it would also be easier to find understanding between the governments and the peoples. Therefore the PEN Centers and their members could perhaps form the avantgarde of this understanding.”

The East German delegate noted it was “the writers, theatre people and artists of the GDR who had blown that trumpet and done a great deal to bring about the collapse [of the wall.] It was they who had called for a huge demonstration on 4th November, at which two million people had gone out onto the streets of East Berlin, demanding changes.” The GDR PEN Center had also “blown the trumpet much earlier when they had supported Vaclav Havel and demanded his release from prison, which, at that time—more than a year ago—had been a thing not without danger in the GDR,” he said.

Yet the breaking up of the Communist regimes with their centralized authority was also leaving in the wake difficult conditions for many writers. Their publishers were closing, their livelihoods shrinking, and the West was taking over. “This did not mean that the writers of the GDR did not wholeheartedly go out onto the streets when they were called on to demonstrate for freedom of expression of writing, of thought and of travel,” the East German delegate said. But “now they had to take the harder road to freedom as Brecht had put it, with a proud bearing, even if they might lose in the process.”

The delegate from Poland saw two major problems ahead: “The first was political: the danger that the remnants of Stalinism might ally with the proponents of extreme right chauvinism. To overcome this danger it was necessary that the new democracies should be stabilized. The second problem was cultural: to find models for cultural life in their countries. They did have a very serious crisis in the domain of publication.”

Because of the collapse of currencies and income in these countries and the withdrawal of state support for arts and culture, it was increasingly difficult for the writers and PEN centers to pay their dues to International PEN and to find funds to travel to conferences and congresses. This situation also existed for many writers in Africa and Latin America where PEN had expanded its centers. In 1990 there were 96 PEN centers around the world.

At the Madeira Congress, PEN set up a Solidarity Fund to which countries with stronger currencies and income could contribute to assist their fellow members. The Assembly of Delegates formalized a procedure for a small, but broad-based committee to make these grant decisions. I was asked by the two American Centers to represent them on the committee, which also included representatives from Zimbabwe, Cote d’Ivoire, Polish, Soviet Russian, Canadian, English and French PEN Centers. Looking back, this new, more democratic process for dispersal of funds foreshadowed major change in PEN International’s own governing structure, change that was to come by the end of the decade.

“The collapse of the Berlin Wall…only provided an entry into the Promised Land…[but did not] overcome all the problems of coping with liberty for the first time,” reflected International Secretary Alexander Blokh to the Assembly of Delegates. “Now was the honeymoon period between East and West, but there was cause to fear that it might not last…While the trumpets of Jericho still sound in our ears, we should take steps to face up to these problems and iron out possible misunderstandings.” For this purpose PEN had held and was holding conferences in Vienna and Budapest with writers in the region.

The Congress discussion around the tectonic changes in Europe and the impact elsewhere occurred in idyllic Funchal, the capital city of Portugal’s Madeira archipelago, surrounded by hills, set on an expansive harbor with gardens and flowers everywhere. A cable car took delegates to the top of the island which offered sweeping views of the hillside neighborhoods and the town below. My specific memories are of bougainvilleas and the beauty of the setting, of the combined joy and worry of colleagues who used to emerge from the “Iron Curtain” to attend PEN gatherings, and now felt relief in their freedom but uncertainty about their lives and the future of their countries.

I remember specifically the establishment of the Solidarity Fund which operated in the 1990’s to help bridge the economic differences within PEN so that all centers could participate. PEN’s policy, though with exceptions, was that a center had to pay its dues in order to vote in the Assembly. Gilly Vincent, who later assisted the International PEN Foundation, remembers working late one winter’s night in the International PEN office when the doorbell rang. She went downstairs to find the Secretary of Polish PEN standing in the shadows at the front door. He had come to pay his Center’s dues in cash. She took the envelope and invited him in so that she could give him a receipt. He replied: “No. We carry no receipts” and vanished into the darkness, she recalls.

My memory of the Madeira Congress includes sharing meals with colleagues from Eastern Europe and with the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, author of the famed Babi Yar who attended as a delegate from the new Soviet Russian PEN Center. [At the Vienna Congress a year later in November, 1991 the Soviet Russian PEN Center got approval to change its name to Russian PEN after the August coup where the Center had issued a statement “true to the best traditions of PEN”.] Yevtushenko, dressed as I recall in rather flamboyant clothes—all white suits (or were they all red or plaid?) commanded attention wherever he went. In the Assembly he spoke in support of a new Belarusian Center which he said would symbolize the democratization of the Soviet Union. He said its members would be helpful in the common fight on behalf of persecuted writers. He spoke in support of the Kurdish Writers Abroad Center changing its name to the Kurdish Center so that Kurdish Writers in Turkey wouldn’t be accused of “separatism” for joining it. And he supported PEN holding a conference in Alexandria, Egypt, where he said PEN must do everything possible to help Salman Rushdie and must ask Arab colleagues in Alexandria for support.

Richard Bray (PEN USA West Executive Director ), Carolyn See (PEN USA West President), and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman at the 55th PEN Congress in Madeira, Portugal

At the Writers in Prison Committee meetings and at the Assembly, PEN delegates also focused on the continuing crackdown in China, on the persecution of writers, editors and publishers in Turkey, Myanmar, Vietnam, Sudan, Cuba, and El Salvador. They protested the house arrest of the renowned novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer in Indonesia. In May, 1990 PEN recorded 381 cases of writers in prison or banned. In spite of the changes in Eastern Europe, the numbers of persecuted writers had not declined worldwide, and there were still some cases in Central and Eastern Europe. PEN resolved to act in all these areas, but the seismic shift in the political landscape of Europe held the focus for the 55th Congress whose theme for the literary sessions was Language and Literatures: Unity and Diversity.

The breakdown of the Communist states was already leading to heightened nationalism, in no place more acutely than in the Republic of Yugoslavia. While most PEN members defended the move towards freer and more tolerant societies, there were some who espoused the nationalistic sentiments that led to the war which eventually broke out in the Balkans. A few took leadership roles in that conflict and separated from PEN which had centers in the former Yugoslav republics—Serbian PEN, Croatian PEN, and Slovene PEN. Only Slovene PEN attended the Madeira Congress. Slovene PEN had long been the annual host for PEN’s Peace Committee which met in Bled, Slovenia, an idyllic town on a lake where it was difficult to imagine war.

But war was on the horizon in the Balkans. What no one anticipated was that war was also on the horizon in the Middle East for in less than three months after the Madeira Congress, Iraq invaded Kuwait. By January, 1991 America and 39 other nations were at war with Iraq. The upcoming PEN Congress in Delphi, Greece had to be cancelled; the conference in Alexandria had already been cancelled at the Madeira Congress. Two months later, in March 1991 the first shots were fired in the Balkans in a war that would last four years.

Next Installment: PEN in Times of War and Women on the Move

PEN Journey 5: PEN in London, Early 1990’s

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey might be of interest.

I moved to London where International PEN is headquartered in January 1990 from Los Angeles. I came with my husband and my 9 and 11-year old sons who rarely wore long sleeves, let alone coats or jackets. A few weeks into our resettlement, London spun in its first major tornado of the decade with hail and winds whipping at hurricane force and cars and trees toppled and a few rooftops airborne. The weather was highly unusual for London. Our family, who was still in temporary housing, took the unwelcome weather as a welcome of sorts, signaling that we might just be in for an adventure. Did you see that roof flying…!

There were still complaints: only four television channels, movies strictly restricted by age and when you did get into a theater, you had assigned seats, milk that went bad in a day, delivered on the stoop in glass bottles, a refrigerator that barely held enough food for a day, appliances that came without plugs…And where was the sun?

Yet the magic of the city quickly affected us all. My youngest son discovered the best skateboarders lived in London, and London (and England) was full of history and castles, and my oldest son, who was soon moved ahead a grade in school because he was highly talented in math, met students from all over the world in his class at the American School, a few of whom talked and imagined in his orbit. He was put on the rugby team to help socialize and the following year on the wrestling team, where he eventually, as an adult and by then dual citizen, wrestled for Great Britain in the Olympics.

For me, finding home in London meant connecting with PEN, both International PEN and English PEN. Writers can be members of more than one PEN center, though can vote with only one center. I’d begun my PEN journey in Los Angeles at PEN Los Angeles Center (changed to PEN USA West). When my second book was published, I also joined PEN American Center, based in New York, and now in London. I joined English PEN, the oldest and the original PEN center since the organization was founded by British writers in 1921. International PEN and English PEN had separate offices, but the Administrative Secretary of International PEN and the General Secretary of English PEN were longtime friends and actually lived next door to each other in Fulham. The two organizations worked independently, yet closely together.

Early on I visited International PEN’s office, headquartered in Covent Garden on King Street in the Africa Centre. To get to the office at the front of the house, you had to go through the Africa Book Shop on the first floor. PEN had two rooms with several desks in the larger room with papers stacked everywhere. There was a filing cabinet and a photocopier and just enough space to squeeze between to get to the desk looking onto the street.

International PEN was kept functioning by the stalwart and efficient Elizabeth Paterson, who I don’t recall getting angry at anyone even as the work piled on and people around the world in PEN centers asked more and more of her, including the smart, demanding International Secretary Alexander Blokh. Alex flew in every month, usually from Paris, and displaced the Writers in Prison Committee’s small staff from the second office in order to conduct the business of PEN around the world. Alex was a former UNESCO official, and at that time UNESCO was one of International PEN’s major funders. When UNESCO was formed, according to Alex, it established organizations for the various arts, but when it came to literature, it recognized that PEN already existed, and so its outreach and funding funneled through PEN. Over the years PEN has grown more and more independent of UNESCO support.

Elizabeth, with her quiet intelligence and subtle humor, managed to keep International PEN running day to day while Alex developed the literary and cultural programs with the centers and the standing committees—the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, the Peace Committee, and the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC). The WiPC tended to operate more autonomously with its elected chair Swedish publisher Thomas von Vegesack and before him Michael Scammell. When I arrived in London, there was also a petite gray-haired woman Kathleen von Simson, a volunteer who’d helped manage the Writers in Prison Committee work for years. PEN had recently hired a paid Coordinator Siobhan Dowd whose task was to professionalize the human rights work, and Siobhan hired researcher Mandy Garner. The two of them worked in the tiny second room. Siobhan eventually crossed the ocean to head up the Freedom to Write program at American PEN.

Fall 1990. Left to right: Elizabeth Paterson, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Per Wastberg (former PEN International President), Siobhan Dowd, Bill Barazetti

Also finding space on King Street was the Assistant Treasurer (and later International Treasurer) Bill Barazetti, who at that time was an unsung hero from World War II. It was later publicized that Bill had smuggled hundreds of Jewish children out of Prague with false identity papers he arranged. He was a wiry gray-haired former intelligence officer who’d also interrogated captured German pilots. Alex Blokh, whose pen name was Jean Blot, was an exiled Russian Jew, a lawyer and had also been active in the French Resistance during World War II, and Elizabeth had endured the bombings in London during the War. Though it was 1990 and the Berlin Wall and other barriers which had gone up after World War II were now falling, in the PEN office there was still a feeling of that post-War period, an abstemiousness and a fortitude of the dedicated amateur who knew what sacrifice was and endured no matter what. I couldn’t articulate the atmosphere at the time, but as an American born after the war, grown up in Texas and moving to London from Los Angeles, I felt the contrasts and the constraints. One small incident I remember was when a donation for a baby gift for the newly hired Sara Whyatt was being gathered. I offered £20 for the pot and was told by Elizabeth, “Oh, no, that amount would embarrass her.” The concept of anyone being embarrassed by a pooled £20 contribution silenced me. I put in £10 instead, still considered a large amount. Because I was new and an American, I tried to listen and learn, but I understood expectations and horizons were different.

A generation of my own joined the office in the persons of Jane Spender, a former editor, smart and literary who worked with Elizabeth and later Gilly Vincent, who took on the part time assignment to help with development work for the eventual International PEN Foundation. (see PEN Journey 4) Later Gilly became General Secretary of English PEN. I quickly learned to respect the differences; the American way was not the British way. I remember a fundraising event in which there must have been 20 major English writers featured and attending, and the ticket price was £25. The PEN Foundation netted perhaps £3000 that evening. In New York with that line up of writers, I am confident American PEN would have added at least one, if not two, zeros to the proceeds, but we were in London, and the event was not a glittery affair but more like a large family gathering of literary friends at someone’s home.

PEN International moved its offices in 1991 from Covent Garden to Charterhouse Buildings in Clerkenwell nearer the City of London. The new offices were on the top floor of a bonded warehouse, and I never met anyone who didn’t arrive breathless after climbing the steep four or five flights of stairs. There was no elevator, but there was an outside hoist where PEN could load supplies and mail out the window and drop or raise these to and from the ground, preferably not in the rain. Elizabeth set the door code as the beginning and ending years of World Wars I and II, an 8-digit code everyone could remember. The offices at Charterhouse Buildings were spacious compared to King Street—two large airy rooms, one for the Writers in Prison Committee and one for all the other work of PEN, a spacious entry room used as a meeting area and a smaller private office where the International Secretary could work or small meetings could be held. All the rooms were painted “magnolia”–a creamy white/yellow color. The full-time staff by then was, I think, three, along with four or five part-time staff and volunteers, including Jane Spender, Peter Day, editor of PEN International magazine, Bill Barazetti and later his daughter Kathy and occasional interns.

When Siobhan prepared to leave for the U.S., Thomas asked me to interview candidates with him for her replacement. Between interviews he explained to me his view of England in the constellation of Europe by a story of when a fog settled over the English Channel and the headline in a British paper announced: Continent Isolated. Later, when the Channel Tunnel finally connected Great Britain to France in 1994, I sent Thomas a note and a copy of the headline from a British paper: “You’ll be glad to know, Thomas: Continent No Longer Isolated, the headline read.

Thomas and I agreed on the best candidate, and PEN hired Sara Whyatt as the new Program Director of the Writers in Prison Committee. Sara came to PEN from Amnesty and set about further professionalizing WiPC’s research and advocacy work. Sara and Mandy split up the globe, with Mandy focusing on Latin America and Africa.

Across London in Chelsea, English PEN rented offices from the London Sketch Club on Dilke Street where it held weekly literary programs, a monthly formal dinner, an annual Writers Day Program honoring one writer—Arthur Miller, Graham Greene, and Larry McMurtry were three I recall—and a mid-Summer Party. The literary programs and dinners, held in the Sketchers studio and bar, featured writers such as Michael Ignatieff, Germaine Greer, Michael Holroyd, Jan Morris, Rachael Billington, A.L. Barker, Penelope Lively, Andrew Motion, A.S. Byatt, Margaret Foster, William Boyd, Margaret Drabble, Iris Murdoch, and frequently Antonia Fraser, Harold Pinter and Ronald Harwood, just to name a few.

When I moved to London and joined English PEN, the General Secretary Josephine Pullein-Thompson, a stalwart writer/member, managed the organization and kept it running with minimal staff and with active members. Author of young adult novels, Josephine wrote books about young girls and horses. When I close my eyes, I can hear her gruff voice and see her square face and think of horses. She was pragmatic and no-nonsense and what I think of as the epitome of a certain era of British resolve. She befriended me early, I think, because I was focused on a task—getting charitable status for PEN International which ultimately allowed English PEN to claim the same. It was Josephine years later who nominated me as a Vice President of International PEN.

Members of English PEN were passionate about PEN’s mission to protect and speak up on behalf of writers under threat in oppressive regimes. Among activities, members, including notable British writers such as Ronald Harwood, Harold Pinter, and Antonia Fraser, who were good friends, and Moris Farhi, a Turkish/British novelist with a great beard, great girth and great heart, who later succeed me as Writers in Prison Chair, and dozens of other English PEN members held vigils, often by candlelight. They protested outside embassies of countries where writers were in prison. They got press coverage and ultimately helped secure the release of writers, particularly those in former Commonwealth countries like Malawi.

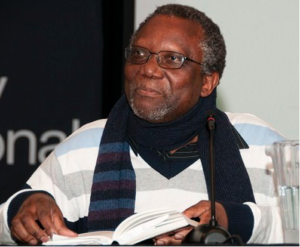

Malawian poet Jack Mapanje recalled his spirit lifting when he saw the press clippings of Harold Pinter and others protesting outside the Malawi Embassy in London on his behalf. When he was released, he resettled in England and joined English PEN.

Jack Mapanje

Next Installment: Freedom and Beyond…War on the Horizon

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

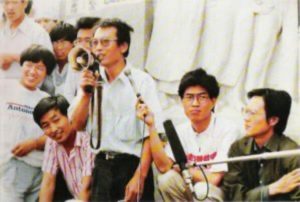

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

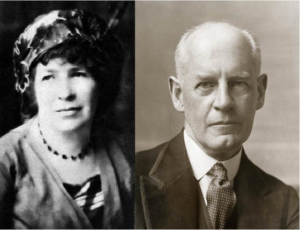

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International

Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance

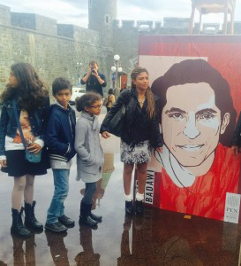

Of all the lively discussions, the literary evenings, multiple resolutions generated at PEN International’s 81st Congress last week in Quebec City, the image that stays in my mind is of the petite wife and children of Saudi blogger and editor Raif Badawi standing in a puddle on the plaza by his picture in the early morning, along with delegates from PEN centers around the world.

His wife and children now live in Quebec, which has also offered Raif Badawi a home, but he remains in a Saudi prison with a ten-year sentence and 950 more lashes of punishment, then a decade long ban on travel, all for setting up a digital forum to encourage social and political debate within Saudi Arabia. He has been found guilty of “insulting Islam” and “founding a liberal website.”

The PEN Congress, which hosted writers from 84 centers in 73 countries, featured three writers with “empty chairs,” including Raif Badawi, Eritrean poet, critic and editor Amanuel Asrat and murdered Honduran journalist Juan Carlos Argenal Medina. PEN called for the release of Badawi and Asrat and justice for Medina. It also targeted the cases of writers imprisoned, threatened, killed or at risk in Bangladesh, China, Cuba, Eritrea, Honduras, India, Iran, Mexico, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Tibet, Turkey and Vietnam.

Badawi’s message via his wife to PEN members after receiving an earlier PEN Canada One Humanity Award was: “We want life for those who wish death to us, and we want rationality for those who want ignorance for us.”

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”–2

(As part of International PEN’s celebration of the 50th anniversary of its Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) which works around the world on behalf of writers who are imprisoned, threatened and killed because of their work, the former chairs of the WiPC have been asked for brief personal memories of their years. For me those years were 1993-1997.)

My years as Chair of International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee began in a way with Salman Rushdie and ended, or at least were framed, by Ken Saro Wiwa. Both were global cases that mobilized writers and others around the world to protest the edicts of governments that tried to stifle dissent and imagination by killing the writer. Rushdie survived; Saro Wiwa did not.

I was elected Chair at the International PEN Congress in Santiago de Compostela, a medieval city in the hills of Northern Spain. The surprise guest at the Congress was Salman Rushdie. At the time Rushdie made few appearances and traveled clandestinely with extensive security, though when he arrived at the hotel, he confronted hundreds of people gathered on the plaza who’d come not to see him, but Julio Iglesias, the Spanish singer, who happened to arrive at the same time.

Rushdie addressed the PEN Congress under tight security. Though the fatwa calling on Muslims around the world to kill Rushdie had been issued in 1989, his case still loomed and defined that period as PEN and the freedom of expression community came to terms with the threat of radical Islam to free expression.

A few days later a young woman in Bangladesh offended militant Muslims and local mullahs with her novel criticizing Muslims attacking Hindus in communal violence in India. Death threats and fatwas were issued against Taslima Nasrin by those extremists. As community pressure built, the Bangladesh government temporarily withdrew her passport and took out an arrest warrant against her for “deliberate and malicious intention of hurting religious sentiments….” At one point it was reported that the snake charmers in Dhaka threatened to release their snakes into the city if she wasn’t prosecuted.

The case of Taslima Nasrin took many turns, including a clandestine meeting in a hotel restaurant in London where the WiPC director and I went to see a young man who’d claimed on the phone to be Taslima’s brother. We had a spotter at a table near the door in case of trouble, and MI5, or perhaps it was MI6, we thought were watching nearby. The man turned out in fact to be Taslima’s brother, and he was trying to get her safely out of the country. PEN worked with her lawyer to secure her safe exit from Bangladesh in the dark of night, and she was flown to Sweden where Swedish PEN helped find her refuge.

Ken Saro Wiwa, the popular Nigerian writer, opposed the brutal regime of Sani Abacha and championed the rights of the Ogoni people in an area of Nigeria where oil companies produced and polluted the landscape and shared few proceeds with the local population. Ken was imprisoned, along with others, charged with the murder of four Ogoni leaders, sentenced to death and given no right of appeal.

PEN and the freedom of expression community mobilized, challenging the charges and the sentence and holding meetings in Parliaments with national leaders, staging readings and mounting vigils around the world, particularly in the countries of the British Commonwealth and in the U.S.

During that period I moved from London to Washington, DC. where each day I called to get an appointment with the Nigerian Ambassador. Finally, one morning when I was actually in New York, I got a call saying the Ambassador would meet with me. I quickly got a plane back to DC and along the way called the Freedom to Write director at PEN American Center and asked her to arrange to have another writer meet me at the embassy. The writer didn’t need to do or say anything; I just wanted there to be two of us to add weight to our delegation. As it turned out, the Ambassador was suddenly bid to the U.N. in New York so we crossed in the skies, but in Washington I met with the second and third diplomats at the embassy, arguing for Ken Saro Wiwa’s life. Midway through the meeting, a fellow writer arrived and sat like an anchor on the other end of the sofa. For all the arguments presented and all the nodding of heads and taking of notes, I feared at the end of the meeting that the decision to execute Ken Saro Wiwa had already been made.

On November 10, 1995 representatives of human rights organizations—PEN, Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and others—were outside the Nigerian Embassy in Washington to protest and seek another meeting when the word came out that Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged that morning in Port Harcourt. The shock of his execution was felt around the world, not only in the freedom of expression community but with the many governments which had also been involved in the protest.

Most colleagues I’ve worked with over the years can tell where they were when the fatwa was issued against Salman Rushdie and when they heard the news of the execution of Ken Saro Wiwa. These two cases were seminal, changing the landscape of the work that was done. Rushdie’s foreshadowed a threat which knew no national boundaries, and Ken Saro Wiwa’s highlighted our limitations.

During those years there were hundreds of cases in China, Turkey, Russia, Algeria, Burundi, Korea, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Peru, Mexico, Guatemala, Syria, Ethiopia, Egypt, Rwanda,– cases in more than 60 countries–all important, many of whom were released, some of whom were killed and a few of whom still remain in prison.

“If the face of global fear used to be a face across a border, it is now the face of a neighbor once tolerated,” I reported during that period. “In Bosnia, Kosovo, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Greece, India, Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Bangladesh, Georgia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tajikistan, Egypt religious and/or ethnic strife has set portions of the population against each other.”

At the PEN Congress in Prague in 1994 my report noted, “Five years ago, the March 1989 Writers in Prison case book listed among our main cases Vaclav Havel and a dozen other Czech writers. Today with the sea change in global politics, PEN has no cases in the Czech Republic. The Writers in Prison work often rides the tides of larger political forces, but in that turbulence, the individual writers connect to each other through the work of the Writers in Prison Committee, through letters to the threatened or imprisoned writers, letters to governments on the writer’s behalf, through acts as simple as a German PEN member sending toothpaste and a toothbrush to an imprisoned South Korean writer or a Norwegian PEN member finding an optician to send free glasses to a recently released Cuban writer, or to acts as complex as Swedish PEN assisting in the safe departure and relocation of our Bangladesh colleague.”

(PEN’s WiPC was formed in 1960, the year before Amnesty was founded. Further information on the work and cases during this half a century when human rights became an important part of the global dialogue can be found at “Because Writers Speak Their Minds: 50 Years of Defending Freedom of Expression.”)