Posts Tagged ‘Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’

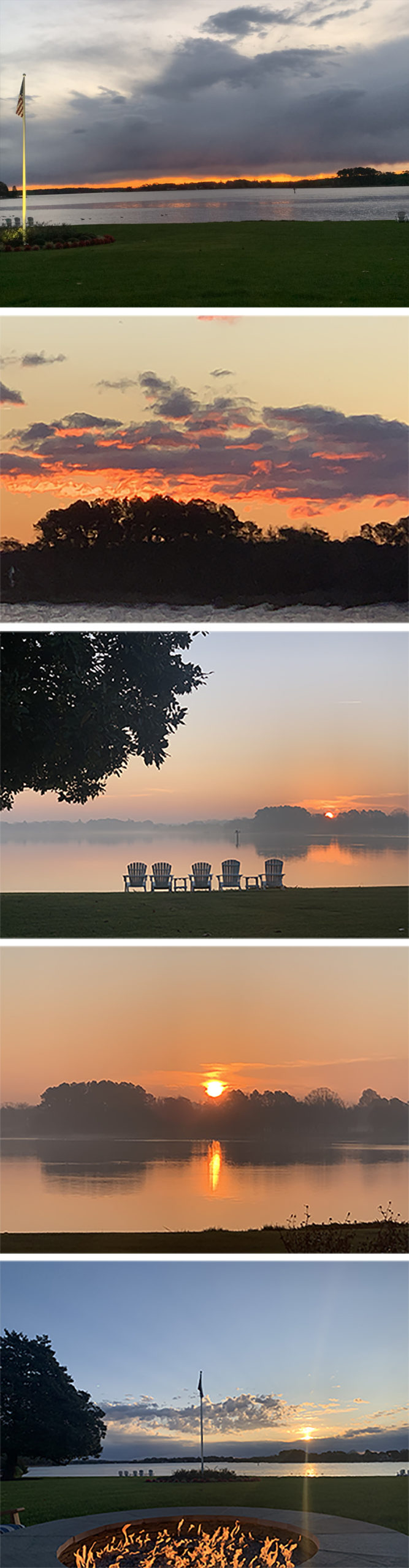

In the Morning…

As many Americans, I have watched with disbelief and sadness events that have taken place in my country and in my home city of Washington, DC over the last days. I have felt unable to add words. This morning I rose early to watch the sunrise on the Eastern Shore of Maryland where I’ve been living this year.

I listened for inspiration. I wasn’t seeking political answers or recriminations, justifications or blame. I wanted inspiration to move forward. I share here the verse that came into my thought and the photos of the morning:

“The night is far spent, the day is at hand: let us therefore cast off the works of darkness, and let us put on the armour of light.” —Romans 13:12

(Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman)

I have a better feeling about tomorrow…

I am living in the country for the first length of time in my life. I wake up most mornings to light lifting the sky out my bedroom window which faces east—a vibrant red line on the dark horizon. Slowly the color fades to orange then yellow and then a pale pink as the sun sneaks up behind the land across the river.

As the sky grows lighter, I stumble out of bed, bundle up and go downstairs, make a quick cup of tea, turn on the fire pit and sit outside with my dogs to watch the world fill with light before the sun itself appears, a throbbing yellow globe through the trees. Some mornings a cloud settles on the horizon, and I see only the effect of the sun—light cast upward, shimmering pink splashes on the clouds above until the sun finally emerges through the clouds and greets the day.

I listen to the geese waking up, honking to each other before they take flight. An American flag blows on a flag pole by the river. On a windy day it flaps wildly and on other days it luffs in the breeze.

For the past year I have been living on the Eastern Shore of Maryland where oyster and crab boats quietly troll by on the river in their season. I live in the area near where James Michener wrote his doorstop-size novel Chesapeake. In fact our good friends, two of the few people we have seen regularly during this pandemic year, live in the house where Michener wrote his book.

For the first months here, I listened to Michener’s Chesapeake every day at lunch as I took a break from writing. For ten months, I have eaten the same lunch—tomato soup, rice crackers with melted chips of cheese, hard-boiled egg, grapes and frozen yogurt bar—and the same breakfast—coconut yogurt with blueberries, raspberries and slivered almonds and cup of decaf coffee—and though dinner varies, usually a salad with another hard-boiled egg, maybe tuna, few more rice crackers, another frozen yogurt. I eat the same meals because I don’t like to cook and have little imagination when it comes to food, so without planning, the routine has meant that everything again fits me in my closet. I bike every morning on a stationary bike and swim most afternoons after work is done.

Swimming at dusk and sitting by the fire pit at dawn are the particular times when I listen. I try to hear the harmony in the universe, not the arguing of political opinions nor the statistics of covid nor the rancor nor the violence of citizens intolerant with each other.

I look up at the sky and listen. On more than one occasion, clouds have broken open and a shaft of light has fallen on the water, or a pageant of clouds has swept across the blue with the wind rising, or some days the air is so still I can hear the river flowing. Nature reminds me there is a larger perspective, and if I listen, there are harmonies to hear, inspired thoughts to think. Hearing the harmony comes first and then…

I have a better feeling about tomorrow.

(Photo credits: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman)

Nobel Peace Prize for Liu Xiaobo Ten Years After

PEN International marks the ten-year anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to writer, literary critic and human rights activist Liu Xiaobo on 10 December 2010. PEN’s Liu Xiaobo Anniversary Campaign acts as a commemoration of Liu Xiaobo’s life, his contribution to Chinese literature, and his selfless work promoting basic freedoms in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The campaign also highlights the cases of writers Gui Minhai, Kunchok Tsephel, Yang Hengjun and Qin Yongmin who are currently detained by the PRC government. The campaign seeks to raises awareness of their situation, to boost advocacy work on their behalf and to ensure that they and their families feel supported and not forgotten.

The following links to PEN’s campaign. Below is text and Chinese translation of my video tribute to Liu:

Hello, I’m Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Vice President Emeritus of PEN International.

您好!我是乔安尼•利多姆-阿克曼,国际笔会荣休副会长。

Ten years ago, essayist, poet, activist and PEN member Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace. Liu envisioned and worked towards a peaceful and democratic pathway for China. Beginning with the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and through the subsequent decades, he spoke out and wrote and gathered people and ideas in support of a China where individual freedom was valued and protected.

十年前,散文家、诗人、活动家、笔会成员刘晓波成为首位荣获诺贝尔和平奖的中国公民。刘先生设想并致力于中国走向和平民主的道路。他从1989年天安门广场抗议运动开始,在随后数十年言说和书写,并聚集民众及理念,以支持一个重视和保护个人自由的中国。

In 2008, he and others drafted Charter 08, which set out this democratic vision. He and others gathered hundreds and then thousands of signatures from Chinese citizens who endorsed the vision. Charter 08 did not call for an overthrow of the government so much as a transformation of the way government related to its citizens in a transition to a democratic society that would include freedom of expression and assembly.

2008年,他和其他人起草了《 零八宪章》,阐明这一民主愿景。他们从支持这一愿景的中国公民那里汇集了成百上千人签名。 《零八宪章》并未呼吁推翻政府,而是要转变政府相对于公民的方式,转型为包括言论自由和集会自由的民主社会。

Liu Xiaobo has been called the Nelson Mandela or Václav Havel of China because of his ideas, his activism and his leadership. Like Havel, Liu was committed to nonviolent action as a means of achieving change, and he was an inspired writer.

刘晓波因其理念、言行和领导能力而被称为中国的曼德拉或哈维尔。像哈维尔一样,刘晓波也致力于以非暴力行动来实现变革,他是一位受鼓舞的作家。

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

I first encountered Liu Xiaobo through PEN. After the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989, PEN worked on behalf of the writers who had been arrested in the protest, including Liu Xiaobo. Liu had also been instrumental in persuading students to leave the Square before the soldiers and tanks rolled in to attack and possibly kill them. At the time of Tiananmen Square, I was President of PEN Center USA West. A few years later when Liu was again imprisoned for his writing, I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

我首先通过笔会遭遇刘晓波。在1989年天安门广场镇压后,笔会致力于代表在抗议活动中被捕的作家,包括刘晓波。刘晓波还曾劝说学生离开广场,以免士兵和坦克席卷攻入广场可能杀死他们。在天安门广场抗议时,我担任美国西部笔会会会长。几年后,当刘晓波再次因写作而被监禁时,我是国际笔会狱中作家委员会主席。

Liu Xiaobo then went on to become one of the founders and the second President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), whose members lived inside and outside of China. He was instrumental in establishing the platforms by which these writers could communicate and share ideas about a society where freedom of expression and democratic processes could exist.

刘晓波随后成为独立中文笔会(ICPC)的创始人之一和第二任会长,该笔会成员居住在中国境内和海外。他发挥作用建立起这个平台,这些作家们可以借此平台,交流和分享有关这样一个社会的理念,在那里言论自由和民主进程得以存在。

During the time Liu was President of ICPC, I was the International Secretary of PEN. However, Liu was not allowed out of mainland China into Hong Kong where ICPC had its meetings, and I didn’t get to the mainland until in 2010 after he was arrested for the fourth and final time, so we never met in person, though over decades I have worked with many of his colleagues.

在刘晓波担任独立中文笔会会长期间,我曾担任国际笔会秘书长。然而,他没获准离开中国大陆前往独立中文笔会举行会议的香港,而直到他 第四次也是最后一次被捕后的2010年,我才去中国大陆,因此我们从未亲身见面,尽管数十年来我一直与他的许多同事共同工作。

Liu Xiaobo was the writer the Chinese government feared the most and therefore arrested. Liu was charged as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power” because of his ideas, his writing and his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison. He was the only recipient of the Nobel Prize who was in prison at the time and not allowed to attend the ceremony. Only an empty chair represented him. His wife Liu Xia was also not allowed to attend. Liu Xiaobo died in custody July 13, 2017.

刘晓波是中国政府最害怕的作家,因此而被捕。由于其理念、写作并参与起草和传播《 零八宪章》,刘晓波被指控为“煽动颠覆国家政权”的“国家敌人”。他被判处了十一年徒刑。他是当时在监狱中而未被允许参加颁奖典礼的唯一诺贝尔奖得主,只有一把空椅子代表他。他的妻子刘霞也被禁止出席。刘晓波于2017年7月13日去世。

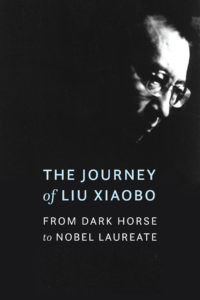

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

他去世后,全世界了解他的作家开始书写他及其作品,书写中国以及自由主义和民主理想之路。今年出版了《刘晓波之旅程:从黑马到诺奖得主》(文文版),包含75篇以上的文章,可能是来自中国民主活动人士的最大笔墨聚会,既是对刘晓波的回忆致敬,也是对中国民主运动的研究。

China’s Democracy Movement and Liu Xiaobo’s legacy still inspire those inside and outside of China, from the mainland to Xinjiang to Tibet to Hong Kong and to neighboring countries engaged in the struggle for political reform and an end to authoritarian rule.

中国民主运动和刘晓波的遗产,仍然激励着中国内外的人们,从大陆到新疆,到西藏,再到香港,再到争取政治改革和结束专制统治的邻国。

Some have said that because of China’s ascendency in the last decade, the legacy of Liu Xiaobo has been reduced to nothing. But a longer view of history shows that the same was said of those visionaries and martyrs for free societies in Eastern Europe and South Africa.

有人说,由于近十年来的中国崛起,刘晓波的遗产被削减为零。然而,更长的历史证明,同样的说法也曾针对过那些在东欧和南非争取自由社会的远见者和烈士们。

Societies move forward and are changed by ideas, by leaders, and ultimately by their citizens. Liu Xiaobo did not aspire to personal power, but those in power came to fear him because he understood how to move ideas into action.

社会向前发展,并通过理念、领导者及最终通过其公民而改变。刘晓波并不渴望个人权力,但是当权者却开始害怕他,正因为他知道如何将理念付诸行动。

As individuals one by one—be they writers, lawyers, academics or others—are put into prison and taken out of the discourse, those in power attempt to maintain their control. That is why it is important to keep an eye not only on the monolith of regimes and government, but to protect the individuals who hold the powerful to account.

当作家、律师、学者或其他人一个接一个地被关进监狱并从话语中带走时,当权者试图维持其控制。这就是为什么重要的不仅是着眼于政权的垄断和政府问题,而且要保护那些向当权者追责的个人。

Liu Xiaobo declared, “Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth.”

刘晓波声言:“表达自由,人权之基,人性之本,真理之母。”

Liu Xiaobo insisted that to transition to a state that one wanted to live in, one needed to have citizens who represented those values even in the struggle.

刘晓波坚持认为,要过渡到一个人们想要生活的国度,就需要有即使在斗争中也代表那些价值观的公民。

I’d like to read from his Final Statement to the judge who sentenced him: “…now I have been once again shoved into the dock by the enemy mentality of the regime. But I still want to say to this regime, which is depriving me of my freedom, that I stand by the convictions…I have no enemies and no hatred…Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy. That is why I hope to be able to transcend my personal experiences as I look upon our nation’s development and social change, to counter the regime’s hostility with utmost goodwill and to dispel hatred with love.”

我要朗读他的《我的最后陈述》,是他写给判决他的法官的:“……现在又再次被政权的敌人意识推上了被告席,但我仍然要对这个剥夺我自由的政权说,我坚守着……信念——我没有敌人,也没有仇恨。……仇恨会腐蚀一个人的智慧和良知,敌人意识将毒化一个民族的精神,煽动起你死我活的残酷斗争,毁掉一个社会的宽容和人性,阻碍一个国家走向自由民主的进程。所以,我希望自己能够超越个人的遭遇来看待国家的发展和社会的变化,以最大的善意对待政权的敌意,以爱化解恨。”

After Liu Xiaobo’s death, a colleague who had known and worked with him for decades was asked if he thought Xiaobo would have changed his statement had he known his end. His friend said No, that his final statement and sentiment that “I have no enemies, no hatred” was at the heart of who Liu Xiaobo was.

刘晓波去世后,一位与他认识并合作了数十年的同道被问到,如果刘晓波知道自己的结局,他是否认为晓波会改变自己的陈述。他的朋友说“不会”,因为“我没有敌人,也没有仇恨”的最后陈述和观点,正是刘晓波其人的核心。

Now Liu Xiaobo’s beloved wife Liu Xia, who is herself a poet, will read one of his poems written to her: “Van Gogh and You” addressed to “Little Xia”:

现在,刘晓波的挚爱妻子,自己也是诗人的刘霞,将朗诵他写给她的一首诗:《梵高与你——给小霞》:

PEN JOURNEY: Introduction—Raising the Curtain: The Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and was asked by PEN International to write down memories. I have done so in 46 PEN Journeys and have been asked to write an introduction to these. Below is the introduction coming last, drawn in part from an earlier blog post of the same title, but not in this PEN Journey sequence.

“In a world where independent voices are increasingly stifled, PEN is not a luxury. It is a necessity.”—Novelist & poet Margaret Atwood, former President of PEN Canada

“…freedom of speech is no mere abstraction. Writers and journalists, who insist upon this freedom, and see in it the world’s best weapon against tyranny and corruption, know also that it is a freedom which must constantly be defended, or it will be lost.”—Novelist Salman Rushdie, PEN member

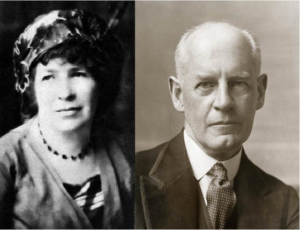

PEN International was started modestly 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catharine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others, conceived if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, they reasoned, at least among writers of Europe.

PEN Founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and first PEN President John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN [Poets, Essayists & Novelists—later expanding to Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Editors and Novelists and now including a wide array of Nonfiction writers and Journalists] spread quickly. Clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, and the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. A decade later when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he donated the prize money to International PEN. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace. Galsworthy spoke about the possibilities of a “League of Nations for Men and Women of Letters.”

Members of PEN began to gather at least once a year in 1923 with 11 Centers attending the first meeting. During the 1920’s writers regardless of nationality, culture, language or political opinion came together. As the political temperature rose in Europe, PEN insisted it was an apolitical organization though its role in the politics of nations was soon to be tested and ultimately landed not on a partisan or ideological platform but on a platform of ideals and principles.

At a tumultuous gathering at PEN’s 4th Congress in Berlin in 1926, tensions rose among the assembled writers, and the debate flared over the political versus non-political nature of PEN. Young German writers, including Bertolt Brecht, told Galsworthy that the German PEN Club didn’t represent the true face of German literature and argued that PEN could not ignore politics. Ernst Toller, a Jewish-German playwright, insisted PEN must take a stand.

After the Congress Galsworthy returned to London and holed up in the drawing room of PEN’s founder Catharine Scott where he worked on a formal statement to “serve as a touchstone of PEN action.” This statement included what became the first three articles of the PEN Charter. At the 1927 PEN Congress in Brussels, the document was approved and remains part of PEN’s Charter today, including the idea that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.” The third article of the Charter notes that PEN members “should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people and dispel all hatreds and champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

As the voices of National Socialism rose in Germany, PEN’s determination to remain apolitical was challenged though the determination to defend freedom of expression united most members. At the 1932 Congress in Budapest the Assembly of Delegates sent an appeal to all governments concerning religious and political prisoners, and Galsworthy issued a five-point statement, a document that would evolve into the fourth article of PEN’s Charter.

When Galsworthy died in January 1933, H.G. Wells took over as International PEN President. It was a time in which the Nazi Party in Germany was burning in bonfires thousands of books they deemed “impure” and hostile to their ideology. At PEN’s 1933 Congress in Dubrovnik, H.G. Wells and the PEN Assembly launched a campaign against the burning of books by the Nazis and voted to reaffirm the Galsworthy resolution. German PEN, which had failed to protest the book burnings, attended the Congress and tried to keep Ernst Toller, a Jew, from speaking. Some members supported German PEN, but the overwhelming majority reaffirmed the principles they had just voted on the previous day. The German delegation walked out of the Congress and out of PEN and didn’t return until after World War II. Their membership was rescinded. “If German PEN has been reconstructed in accordance with nationalistic ideas, it must be expelled,” the PEN statement read. During World War II PEN continued to defend the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. (Today German PEN is one of PEN’s active centers, especially on issues of freedom of expression and assistance to exiled writers.)

PEN was one of the first nongovernmental organizations and the first human rights organization in the 20th century. PEN’s Charter, which developed over two decades, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II. In 1949 PEN was granted consultative status at the United Nations as “representative of the writers of the world,” and is today the only literary organization with formal consultative status with UNESCO.

In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in more than 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries, defend linguistic rights and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia in the late 1980’s and in other countries of the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar where a former prisoner of conscience was instrumental in forming a center there and was its first President. A PEN center is a refuge for writers in many countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

For more than 35 years I have been engaged with PEN, as a member, as the President of one of PEN’s largest centers, PEN Center USA West during the year of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie and Tiananmen Square, as Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), as International Secretary (2004-2007), and continuing as an International Vice President since 1996. I’ve also served on the Board and as Vice President of PEN America (2008-2015). I lived for six years in London, where PEN International is headquartered.

In the run-up to PEN’s Centenary, I was asked if I would write an account of PEN’s history as I’d seen it. I began by posting a blog twice a month, taking on small slices of the history in each narrative. This serial blog of PEN Journeys recounts PEN’s history as I’ve witnessed it as well as history of the period and personal history during those years. The narratives are framed by the times, featuring writers, including the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the protests in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall—PEN members or future PEN members were central in all these events—the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of PEN Centers there; the opening up of Eastern Europe with its PEN centers; the release of PEN “main case” Václav Havel and his ascendency to the Presidency of Czechoslovakia; the mobilization of Turkish PEN members in opposition to recurring authoritarian governments; PEN’s mission to Cuba; PEN’s protests over killings and impunity in Mexico; protests and gatherings in Hong Kong on behalf of imprisoned Chinese writers; the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Peace to PEN member and Independent Chinese PEN Center founder and President Liu Xiaobo.

PEN and its members have played a pivotal role in defending freedom of expression around the world, in challenging systems that trap citizens, and in at least two instances, in taking on the presidencies of the new democracies that emerged. The PEN Charter, which sets out the principles and ideals, has united the global organization and guided its members who have often been at the forefront or in the wings of important historical moments—celebrated and outspoken writers like Václav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk, Yaşar Kemal, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Koigi wa Wamwere, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Arthur Miller, Anna Politkovskaya, Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Carlos Fuentes, Liu Xiaobo. The list is long, and I have had the privilege of interacting with many of them in PEN and also with hundreds of perhaps lesser known, but courageous writers who have stood watch and engaged.

The view of PEN Journey is global though the work is often local. As well as chronicling global events and personal history, PEN Journey recounts the shaping and re-imagining of this sprawling nongovernmental organization, one of the largest in terms of geographic reach. PEN has had to evolve and re-shape itself to serve its 155 autonomous centers. With at least 40,000 members around the globe in more than 100 countries, there are many stories others might tell, but this narrative is a close-up view of a period of time and of the writers who continue to work together in the belief that the world for all its differences and complexities can aspire to and perhaps even achieve “the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”* [*PEN Charter]

Because I tended not to throw away documents over the decades, I have an extensive paper as well as digital archive which I used to refresh memories and document facts. As I dug through files, I came across a speech I’d given which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman speaking at PEN International Conference on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

The talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is ongoing. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King is quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

From Diyarbakir Conference:

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through PEN’s 141 centers in 99 countries. [Now 155 centers in over 100 countries.] They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see for himself this ancient city, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together.

–Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International, March 2005

PEN Journey 46: Wrapping Up

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I finished my term as International Secretary of PEN July 2007 at PEN’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal. I handed over the responsibility to my longtime colleague Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) who would continue to work with the Board, the Executive Director Caroline McCormick, new Treasurer Eric Lax and President Jiří Gruša. We had executed many changes in the last three years, and those who had been involved were continuing and active both in the international leadership and in the PEN centers.

Before the Congress, the staff and PEN members gave me a farewell party at PEN International’s relatively new London headquarters on High Holborn. PEN is about people, and I’d been fortunate to work over many decades with dozens of talented writers who were also competent in organizational work, friends from around the globe who remain friends today.

PEN International Farewell gathering in London 2007 with friends and staff, including Caroline McCormick, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender, Sara Whyatt, Moris Farhi, Peter Firkin, Eugene Schoulgin, Frank Geary, Emily Bromfield, Mitch Albert, Mandy Garner.

As a Vice President, I would continue to work, write appeal letters to governments for the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC)’s RAN (Rapid Action Network) cases, speak when asked and hold meetings in Washington when asked, but I could return to being a writer. American PEN’s Executive Director Michael Roberts asked me to join American PEN’s board. I demurred and said I needed a break, but he and others urged me so in 2008 I joined the board of PEN America but worked at a far less intense pace for the next six years. When American PEN’s new Executive Director Suzanne Nossel came on, I was asked to extend for an additional year as a Vice President while she oriented to PEN’s international work. It is difficult to step away from PEN though most who are engaged find they must for a time, though not too far away.

As I left the historic Senegal Congress that July 2007, I boarded a plane and flew out over the Atlantic to Italy where I met up with my husband by a lake in one of our favorite spots for a vacation. He had patiently waited those three years as I spent 10-15 days a month on the road. In the first week without PEN’s emails and phone calls and conferences, we talked; I wrote, and I read four books in six days.

Back home I soon realized I needed to join the 21st century as a writer. At PEN we had begun to use some tools of social media in publicizing cases of writers under threat, but I hadn’t engaged personally. I remember sitting with a group of women writers in Washington, DC, many younger than me, who were talking about their websites and blogs and Twitter, and Facebook. In 2007 writers having URLs, Twitter handles, Facebook pages was relatively new. Twitter had only launched the year before, and though blogs had been around for a few years, I had never written one. Facebook seemed an odd medium, also only a few years old. I was of the “private” generation; we were not prone to sharing our activities and feelings on a “social” platform. Those of us who’d been journalists were used to having to condense stories, but never to 140 characters which Twitter demanded. We were in a new communications age, and I needed to understand and at least to put a toe in the water, even if I didn’t jump fully in.

Encouraged by friends and agent, I set up a website. The developer urged me to blog. I didn’t want to blog, I explained. I wanted to write fiction and occasional journalism, but I agreed to post a blog once a month. I have done so for over ten years now. Often when I considered what was worth writing about each month, I found myself reflecting on work with PEN. When asked to write about PEN’s history as I’d witnessed it in anticipation of the Centennial, I reasoned I could post twice a month. That seemed a reasonable way to get through PEN’s history year by year. A serial blog. I have sped up the pace since Covid locked us all into our homes and travel has halted. I have now come to an end of this particular PEN Journey though I will write an introduction. I will also reference links to those blog posts I wrote after 2007 when I continued to work with PEN.

In this final post, I want to review a few areas of PEN International I feel I haven’t explored sufficiently, and I want to give a quick view forward of what and who came next.

In Journey’s 7, 8, 22, 25, 26, I touched on the work of the PEN Emergency Fund. I want to highlight that here. Founded in 1971 by Dutch Writer A. (Bob) den Doolaard who had an active role with PEN International, the PEN Emergency Fund fulfilled a missing link in PEN’s work. Doolaard noted that PEN had no mechanism to grant material aid to writers, especially those under threat who had to flee their countries so he and Dutch PEN set up the aid fund based in the Netherlands, operated under Dutch law. The PEN Emergency Fund gives a one-time grant to writers in dire circumstances and is able to act quickly. Over the years PEN’s Emergency Fund has provided rapid support for writers on every continent, especially those in Eastern Europe during the Communist era and those in the Balkans War in the 1990s and also to persecuted writers in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Every year dozens of writers have been helped with grants that have bridged to longer term answers. The Fund operates in close collaboration with PEN International whose professionals furnish the Fund with information and with the PEN centers and members who have contributed to the Fund. I’ve had the privilege of serving on the PEN Emergency Fund Advisory Board for a number of years.

Prizes: As a literary organization, PEN through its centers awards numbers of literary awards, but only a few literary prizes have been awarded by PEN International. Over the years the idea of a PEN International Prize for Literature or even for Peace has arisen. When I first took on the position of International Secretary, we were approached by a donor offering to give PEN $100,000 for the PEN International Prize for Peace. Well-meaning though the donor was, it quickly became clear that PEN International could not accept. The donor already had his first winner in mind—Bono. We explained that any prize would have to be independently judged with established criteria and nominating processes, and in order for PEN to give an annual prize, we would need to have a substantial financial commitment in an account to assure we could afford the prize each year as well as the cost of the judging and ceremony. We named the figure. The discussions broke off though the donor, I think, did find another way to give his prize though not through PEN.

Chimamanda Adichie, PEN David T. Wong International Short Story Prize winner.

The biennial PEN David T. Wong International Short Story Prize did come into being for a time, with a much more modest monetary award for a new writer, open to nominations by all PEN Centers and run by International PEN Foundation’s Gilly Vincent, who later became General Secretary of English PEN. Gilly was a pro and lined up well-qualified writers as judges. The nominations came in from PEN Centers around the world and the winner was often celebrated at PEN’s Congress. One of the first winners for 2002-2003 was a young Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie, who won for her short story “One Half of the Yellow Sun,” submitted by her local PEN Center USA West. The story went on to become the celebrated novel by the same name, and she went on to win wide international acclaim for that and other books. The PEN David T. Wong Prize was one of the first international recognition of her as a writer. The judges for 2003 were William Trevor, Michele Roberts and J.M. Coetzee who won the Nobel Prize for Literature later that year. The 2001 prize had been won by Rachel Seifert, who went on to have her first novel short-listed for Booker Prize.

PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, the PEN Emergency Fund and Oxfam Novib each year do give the Oxfam Novib/PEN International Free Expression Award to writers who work for freedom of expression in the face of persecution. The award is given to writers and journalists committed to free speech despite the danger to their own lives.

Turkey visit—on the roof with Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Carl Morten and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN)

Many other literary awards and literary festivals are hosted by PEN’s centers around the world. I had the pleasure of visiting a number of those, including in Croatia and in Turkey, hosted by the PEN centers.

There are many aspects of PEN’s work I’ve touched on but not explored fully such as the formation of a PEN center, which technically can occur when 20 reputable writers get together and petition the International office. There is a limit of five centers per country; most countries have fewer, and many countries have only one center. The rationale for additional centers has been to reflect linguistic diversity in a country. For instance, Switzerland has French, German, Italian, and Esperanto centers, or to facilitate participation when the land mass is large. The U.S. used to have two centers, one based in New York and one in Los Angeles, but in the past years, the two centers have merged into one PEN America. In Canada where there is both large land mass and diverse languages PEN has two centers—PEN Canada based in Toronto essentially uses English as the primary language and Quebecois PEN uses French. In some countries there are many, many languages as in India, which also has a large landscape and has the All-India Center in Bombay and the PEN Delhi Center. The rationale depends largely on the ambition and needs of the writers on the ground. Often a center will form branches within a country to provide the services and community for writers.

One document I did not include in an earlier post was the rationale from PEN International Vice President and Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer regarding the formation and naming of centers as related to a petition from writers in South Africa to form an Afrikaans Center. I’ve copied it here because it was from one of PEN’s eminent and active members and because it articulated ongoing questions in PEN. Gordimer’s argument did not prevail at the Berlin Congress in 2006 where an Afrikaans Center, not a Pretoria Center, was voted in though the center is based in Pretoria. The reasoning nonetheless is worth considering. The dynamics are ongoing in a number of countries and will likely continue as new centers are added or removed when they grow inactive.

Nadine Gordimer: “Let me make it clear. My objection to the formation of an Afrikaans language PEN club has no significance whatever of any kind of prejudice against my brother and sister South Africans, who are Afrikaans speakers and writers just as I am an English-speaking writer. We have eleven languages in our country. I should have exactly the same objection to the formation of an isiZulu or isiXhosa Club. We cannot have separate-but-equal (shades of apartheid) Clubs for every language, even though most of which have the strong linguistic claim of ante-dating colonially imported English and colonially created Afrikaans. I support a vigorous and linguistically open South African PEN Club, to have local representation in each region, with membership actively pursued among writers in whatever South African languages are theirs. Only such a chapter could have the strength to fulfil our needs…Historic-culturally determined circumstances give us both the necessity to overcome them and the fine opportunity to make full use of them, for our writers and our poly-literature.”

PEN is a breathing, living organization whose main body has been working around the world for a century with new members and centers joining every year as other centers at times have fallen dormant or closed. It is a fellowship of writers, of citizens in civil society holding watch over freedom of expression, linguistic diversity, over literature, and over the imagination and art by which societies flourish. Particular issues and threats change according to the times. PEN declares itself an apolitical organization, yet it is an organization whose central principle and commitment to freedom of expression sets it in the fray of politics since an early warning of a society descending into authoritarianism is the arrest of its writers and the closing down of space for free expression.

Changes in PEN leadership internationally and in centers effect the organization, but the Charter holds the whole body together. The leadership of PEN International used to reside in the President, the International Secretary and the Treasurer as the Executive, which represented the Centers’ Assembly of Delegates between two annual Congresses. The narrative of this PEN Journey has shown the change in the organization and its governance as it has grown and the world in which it operated has altered. PEN International has more than doubled in size over the last three decades to 155 centers in more than 100 countries. It now holds only one Congress a year, and the leadership is a partnership among the President, the International Secretary, the Treasurer, and an elected 7-member Board representing the Centers. Work is facilitated by an Executive Director, a position first hired in 2005, who heads the staff. Depending on the skills and experience and personality of each, the dynamic changes. In my term, I tended to be hands-on as an International Secretary. The President Jiří Gruša with whom I served was engaged as the Director of a Diplomatic Academy and had not been very active in PEN before he took the role of President. I would check in with Jiří before each monthly board meeting, explain the agenda as I saw it, ask if he wanted to add or change any items and if he wanted to attend. Jiří, a former prisoner of conscience, had lived the principles of PEN, understood them and with experience, knowledge and wit was an authentic voice on the international stage. But the day-to-day decision-making and running of the organization he largely left to me and then with the first Executive Director, the Board and the staff.

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President 2015-2021

John Ralson Saul, PEN International President 2009-2015

Jiří’s successor John Ralston Saul, former President of PEN Canada, had been a long time PEN member, active in the organization with experience in governing. He took on a much more active role as President, working with International Secretary Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) and then International Secretary Hori Takeaki (Japan PEN). John traveled the globe visiting PEN centers and government officials and taking on the issues of his period. After John, PEN elected its first woman President Jennifer Clement, former President of PEN Mexico, who took on the work, along with a special focus on the issues of women globally. She spearheaded, along with PEN’s Women Writers Committee, a Women’s Manifesto and later an Imagination Manifesto and will serve until the end of the Centenary Congress in England in 2021. Kätlin Kaldmaa (Estonian PEN) has served as International Secretary during this time along with longtime PEN member Carles Torner as Executive Director.

Unfortunately over the years as PEN’s website has been upgraded, the content has not always been exported so many of the documents and speeches and records have not followed into the digital universe. The narrative is carried in paper files which overflow in my basement and even more in PEN’s and in the memories of PEN members. My own PEN Journey has been an effort to record some of the history and offer a continuity of narrative during a particular period, through the eyes of one PEN member who has had the privilege and pleasure of standing up close for part of that history. I’ve tried to render the direction and actions. The flaws, the missteps of people, including myself, I’ve also witnessed but have largely left to the side in this narrative. My purpose has not been to be a critic nor a hagiographer, nor a novelist, but a reporter, recording the actions and the journey with a touch of personal memoir.

I will leave this journey by quoting from PEN’s Democracy of the Imagination Manifesto, unanimously passed at the 85th PEN World Congress in Manila, Philippines, October 2019:

The opening of the PEN International Charter states that literature knows no frontiers. This speaks to both real and, no less importantly, those imagined.

PEN stands against notions of national and cultural purity that seek to stop people from listening, reading and learning from each other. One of the most treacherous forms of censorship is self-censorship —where walls are built around the imagination and often raised from fear of attack.

PEN believes the imagination allows writers and readers to transcend their own place in the world to include the ideas of others. This place for some writers has been prison where the imagination has meant interior freedom and, often, survival.

The imagination is the territory of all discovery as ideas come into being as one creates them. It is often in the confluence of contradiction, found in metaphor and simile, where the most profound human experiences reside.

For almost 100 years PEN has stood for freedom of expression. PEN also stands for, and believes in, the freedom of the empathetic imagination while recognizing that many have not been the ones to tell their own stories.

PEN INTERNATIONAL UPHOLDS THE FOLLOWING PRINCIPLES:

- We defend the imagination and believe it to be as free as dreams.

- We recognize and seek to counter the limits faced by so many in telling their own stories.

- We believe the imagination accesses all human experience, and reject restrictions of time, place, or origin.

- We know attempts to control the imagination may lead to xenophobia, hatred and division.

- Literature crosses all real and imagined frontiers and is always in the realm of the universal.

Next and final installment of PEN Journey: Introduction—the Curtain Rises

Links below are to blog posts mentioning PEN after 2007. I was not writing official reports of Congresses or WiPC conferences or other events, but reflecting on PEN’s work, cases and the impact of ideas in my own monthly posts, some of which I used in writing this PEN Journey:

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate

March 31, 2020

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

March 20, 2019

Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

May 23, 2018

Women’s Voices Rising (Women’s Manifesto)

February 28, 2018

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

December 7, 2017

Reclaiming Truth In Times Of Propaganda (83rd PEN Congress in Lviv, Ukraine)

September 28, 2017

“Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

September 8, 2017

In Turkey, a show of solidarity with writers behind bars (PEN Turkey Mission)

February 3, 2017

Power on Loan

January 23, 2017

Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

December 27, 2016

Building Literary Bridges: Past and Present (82nd PEN Congress in Ourense, Spain)

October 3, 2016

Call for Help inside Iran’s Evin Prison

May 23, 2016

Spring and Release

March 18, 2016

View on the Bosporus: Rights in Retreat

January 29, 2016

Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

November 30, 2015

Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance (81st PEN Congress in Quebec, Canada)

October 23, 2015

What Are You Not Reading This Summer? (WiPC Conference in Amsterdam)

June 11, 2015

Times and Tides

November 14, 2014

PEN on the Plains of Central Asia (80th PEN Congress in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan)

October 7, 2014

Poets, Pardons and Ramadan

August 2, 2014

Women’s Progress: The Power of a Bridge…and a Double Yellow Line

March 12, 2014

Qatar: A Poet in a Desert Cell

November 1, 2013

The Last Colony?

October 15, 2013

Parallel Universe in a Glassed Concert Hall in Iceland (79th PEN Congress in Reykjavik, Iceland)

September 16, 2013

Living In and Beyond History (WiPC Conference in Krakow, Poland)

May 20, 2013

Two Voices Behind the Iron Doors

April 8, 2013

North Korean Writers in a Land of the Rising Sun (78th PEN Congress in Gyeongju, South Korea)

September 15, 2012

facebook or not?

June 28, 2012

Voices Around the World

January 30, 2012

Bridge Over the Bosporus: Citizenship on the Rise (77th PEN Congress, Belgrade, Serbia mentioned)

September 28, 2011

Tourist in Beijing: A Dance with the Censor

July 29, 2011

Ice Flows: Freedom of Expression

January 29, 2011

In the Woods: On History’s Doorstep

December 22, 2010

Full Moon Over Tokyo (76th PEN Congress in Tokyo, Japan)

September 30, 2010

Introducing Isabel Allende

May 21, 2010

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”–2

March 31, 2010

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”

February 24, 2010

Haitian Farewell

January 18, 2010

Yellow Geranium in a Tin Can

October 27, 2009

China at 60–Fate of Liu Xiaobo?

September 30, 2009

A Time of Hopening (WiPC Conference in Oslo, Norway)

June 24, 2009

“There Will Still Be Light” *

April 30, 2009

The Intensifying Battle Over Internet Freedom

February 24, 2009

Charter 08: Decade of the Citizen

December 30, 2008

China from the 22nd Floor (Hong Kong Conference)

May 28, 2008

OLYMPIC RELAY– A POEM ON THE MOVE

April 21, 2008

Words That Matter

March 4, 2008

PEN Journey 45: Dakar, Senegal: The Word, the World and Human Values

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

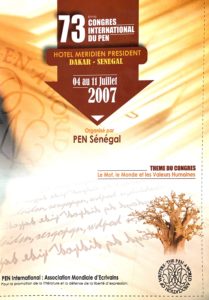

Program for PEN International’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal, July 2007

PEN International’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal July 2007 celebrated the first Pan African PEN Congress with over 200 writers gathered from over 70 countries around the theme “The Word, the World, and Human Values.” The theme had been developed by PEN’s African centers who assisted in the planning of the Congress which brought together writers from every continent as well as from across Africa.

The setting was grand on the rugged Atlantic coast at Le Meridien Hotel. Government luminaries, including the President of Senegal Abdoulaye Wade and Prime Minister Cheikh Hadjibou Soumaré greeted delegates at the opening and closing ceremonies in the tiered auditorium where the Assembly of Delegates conducted PEN’s business. Ministers of Culture, Information and Foreign Affairs hosted dinners in the evening as did the President and Prime Minister.

Because PEN monitored the human rights situation in countries, particularly regarding freedom of expression, PEN vetted carefully countries where it held its Congresses. Senegal had prosecuted four journalists the past year, but none were in detention, and PEN Senegal and the International Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) were advocating to abolish defamation laws used to repress writers across the continent. Senegal in general was an open society for writers. On the few occasions when PEN hosted Congresses in countries with more repressive regimes, it took no assistance from the government and used the occasion to advocate on behalf of the writers.

The 73rd Congress marked the end of my term as PEN International Secretary. At my first Congress as International Secretary, I’d opened with the image of a bridge soaring into the sky, a bridge that had taken decades to construct. I had suggested that for the last decade International PEN had been building an organizational bridge into the 21st century. Having occupied the position of International Secretary for three years on a daily basis, I could attest that PEN was a robust, though occasionally fragile, organization whose bridges across cultures were real, whose joints were welded by the principles of the PEN Charter and by the fellowship among writers.

For me, memories abounded—memories of the ancient city of Diyarbakir, Turkey where Kurdish and Turkish writers translated each other side by side for the first time; the gathering in Hong Kong where writers from mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the diaspora, along with other writers from around the world, met and shared ideas and literature; and the memory of the dungeons of Gorée Island with its dark doorway to the Atlantic, similar to “the door of no return” on Ghana’s Cape (Gold) Coast where the most basic human rights had been violated centuries before when men and women were shipped as slaves to other countries, including to my own.

At the Congress PEN members traveled to Gorée Island off the coast of Dakar to see and to pay homage to this history and through PEN’s work to act on behalf of freedom and human dignity today.

Visit to Gorée Island, Senegal. L to R: Carles Torner (Catalan PEN), Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN), Lucian Kathmann (San Miguel PEN), Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Mamadou Tangara (Gambia.)

A Nobel Laureate in science once said, “Discovery consists in seeing what everyone else has seen and thinking what no one else has thought.” That could be said of the writer whose imagination saw bridges between people and cultures where others saw clashes and conflict.

Before each Congress I made a point of reading histories of PEN, particularly the history of the place where PEN was holding its Congress. The 73rd Congress was only the second time PEN’s whole international body had met in Africa. Forty years before a PEN delegate at the 35th Congress in Abidjan, Ivory Coast recalled ascending the stairs of the Congressional Hall between a double row of guards dressed in scarlet and gold with raised sabers. At that Congress PEN members took special notice of writers in prison in Communist and noncommunist countries. There were not many PEN centers in Africa then, but PEN Senegal existed. At the Congress the prior year in New York City in 1966, delegates from the Ivory Coast and Senegal had attended as had observers from Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria. By 2007 PEN had 15 centers in Africa, including in those countries whose writers had visited the New York Congress. Today PEN has 28 African centers.

At the Dakar Congress, writers from regions who hoped to develop PEN centers observed, including Uighur writers, Afar-speaking writers and writers from Tunisia, Bahrain, Iraq and Jordan, all of whom eventually formed PEN centers. Forty years ago International PEN also had observers from the Soviet-bloc. In all these instances, PEN had acted as a bridge to writers who aspired to share their literature and to work for freedom of expression in their societies.

PEN International President Jiří Gruša addressing PEN Assembly of Delegates at 73rd Congress, 2007.

In Dakar, International PEN President Jiří Gruša noted, “International PEN and its Centers are glad to be gathering in Senegal, a country which holds literature in high regard, in part because its first President Leopold Senghor was the internationally renowned poet and also a Vice President of International PEN.”

Mbaye Gana Kébé, Senegal PEN President, affirmed, “Senegal has remained a welcome land at the crossroads of all civilizations. In addition to that we have its democratic ideal and respect of human rights. This Congress taking place here consecrates a lasting and beautiful tradition of African hospitality.”

International PEN Board Member Mohamed Magani (Algerian PEN) talking with Alioune Badara Bèye (General Secretary Senegal PEN).

The Congress theme “The Word, the World, and Human Values” was explored thorough round table sessions including “Literature and the Oral Tradition” and “The Role of Contemporary African Literature in Intercultural Dialogue” and at International PEN’s first literary event “Freedoms” held outside under the stars. Hosted with TrustAfrica, a new African foundation that promoted peace, economic development and social justice, the evening and the panels featured writers from across Africa, noted Senegalese PEN Vice President Amadou Lamine Sall and General Secretary Alioune Badara Bèye who were instrumental in arranging the Congress. Writers included Bernard Dadié (Ivory Coast), Jean-Baptiste Tati Loutard (Congo), Fernando d’Almeida (Cameroon), Dieudonné Miuka Kadima Nzuji (Congo), Tanure Ojaide (South Africa), Frédéric Pacéré Titinga (Burkina Faso), Aminata Sow Fall and Pr. Abdoulaye Elimane Kane (Senegal), and Jack Mapanje (Malawi).

In the hotel’s meeting rooms, PEN’s standing committees adjourned. The Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), chaired by Karin Clark (German PEN), focused on criminal insult and defamation laws, particularly in Africa. These laws endangered writers and resulted in imprisonments. During the previous year WiPC had followed 1100 cases worldwide of attacks on writers, ranging from killings, long term detentions, threats, and harassments. Around 320 of those had been in Africa.

PEN also brought attention to the refugee crisis in Iraq with an appeal for translators, writers and journalists who were being targeted for death because of their work. In a resolution supported by American PEN and passed unanimously, International PEN urged the US to protect these refugee writers and translators and to increase funding for UNHCR and other refugee services and remove barriers to resettling Iraqi refugee writers and intellectuals.

The Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC), chaired by Kata Kulavkova (Macedonia PEN), considered the mounting threats to linguistic diversity in an English-dominated world. Delegate Esther Allen (PEN America) presented “To Be Translated or Not to Be: Globalization, Translation, and English,” a major survey of barriers to the exchange of literature and entrance into the international literary marketplace. The Assembly of Delegates passed a resolution calling on UN member states to comply with international conventions on linguistic rights.

International PEN Women Writers Committee Conference, Dakar, Senegal, July 2007.

The Women Writers Committee (IPWWC), chaired by Judith Buckrich (Melbourne PEN), met during the Congress and also at its own conference right after the Congress to examine the challenges faced by women writers, especially as related to freedom of expression and censorship, particularly in Africa. The writers also discussed women’s literacy and educational opportunities and explored the publishing potential for voices which struggled to be heard.

PEN’s Peace Committee, chaired by Edvard Kovač (Slovene PEN), met with an appeal to bring writers in countries at war together in an exchange of literature and ideas such as at a recent meeting between Turkish and Kurdish members

The Writers in Exile Network, chaired by Haroon Siddiqui (PEN Canada), reported that PEN continued to assist resettling writers under threat, often at universities, and also through partnership with the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN).

International PEN’s Executive Director Caroline McCormick and her team worked before, during and after the Congress on regional development. “International PEN is working in partnership with its African Centers to address challenges which they have identified in the region. Essential to this work is the role of continued engagement with reading, writing and ideas in bringing about change and empowering civil society.”

Each African center had its own history and focus though many overlapped. PEN Senegal, the first and oldest center in Africa, was dedicated to raising the profile of young and new unpublished writers and published an anthology of young writers and actively promoted work through its publications and competitions. The center had the advantage of a permanent writers house which was a drop-in center and focal point for the writing community and also accommodated visiting writers.

Guinean PEN had been established by the Women Writers Association of Guinea, which made it one of few African centers that had majority of women writers as members. Headed by Zeinab Koumanthio Diallo, President of Guinea PEN, the center ran its own museum and cultural center and raised the majority of funds through income-generating activities, including performances and cultural activities with a focus on literature and on raising awareness of social issues to include communities who didn’t normally have access to the world of literature. Projects included promoting reading in rural agricultural communities and using literature to support the rights of women and girls.

PEN International’s next regional focus would be Latin America in anticipation of the 2008 Congress. After a vigorous debate at the Congress, the Assembly of Delegates voted to move the 2008 Congress from Oaxaca, Mexico because of challenges to freedom of expression there to Bogotá, Colombia, hosted by Colombian PEN which was monitoring closely, along with International PEN, the situation for writers there.

Members of PEN International Foundation Board, final meeting. L to R: Fawzia Assaad (Suisse Romand PEN), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director), Karin Clark (German PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (PEN International President), Britta Junge Pedersen (PEN International Treasurer), Eric Lax (PEN USA West).

The work of the 73rd Congress included the final disbanding of the International PEN Foundation which had served its purpose for over a decade as a charitable entity that existed with its own board alongside PEN International and enabled PEN International to receive charitable donations. Now that British charitable tax law had changed, PEN International, which was headquartered in London, could finally be incorporated as a charity.

The work of the Assembly of Delegates included elections of:

—International Secretary Eugene Schoulgin (PEN Norway), former WiPC Chair and International PEN Board member,

—Treasurer Eric Lax (PEN USA West), former International PEN Board member and former President of PEN USA West,

—International PEN Board members: Mike Butscher (Sierra Leone PEN), Haroon Siddiqui (PEN Canada), Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN) and Kristin T. Schnider (Swiss German PEN),

—Vice Presidents: Margaret Atwood (PEN Canada) for service to literature and Niels Barfoed (Danish PEN) for service to PEN.

PEN International Board Meeting and Staff in Dakar, Senegal, July 2007.

Three new PEN centers were welcomed: Iraq, Jordan and Afar-speaking.

The Assembly adopted twelve resolutions from the Writers in Prison Committee focusing on the imprisonment of writers in China, Tibet, Iran, Uzbekistan, Eritrea, Cuba, Turkey, Tunisia and Vietnam, the killing of journalists in Mexico & Afghanistan and the forced closure of television stations in Venezuela.

One unexpected controversy arose just a few weeks before the Congress when the British government conferred a knighthood on Salman Rushdie. The act stirred disputes in literary and political circles which threatened to follow us to the Congress. We came prepared should questions arise. I don’t recall now if the question was asked at the closing press conference where Jiří and I sat in our new African dress which had been given to us by the Congress hosts. Along with the President of Senegal PEN we recalled the successes of the Congress and the African programs which PEN International committed to continuing.

Rather than revisit the Rushdie controversy, I quote here PEN International’s response from Vice President and Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer: “International PEN deplores the reaction of extremists to the honor conferred upon one of the world’s great writers, Salman Rushdie, by the Queen of the United Kingdom for his services to literature. The appalling reaction from extremists threatens not alone the principle of freedom of expression as a basic tenant of justice, but seeks to decree the violent end to the life of a writer, solely on the grounds of written words that did not call for any aggression against any group or individual.”

My personal memories of the impressive Dakar Congress include being driven around in a limousine as International Secretary. Because PEN Board Member Eric Lax was hobbling on crutches with his foot in a cast, he also hitched a ride. I would have been happy to go on the bus, but we both appreciated the gesture.

Before each PEN Congress while I was International Secretary, I studied French. I hired a tutor and talked with her for hours, practicing conversation and comprehension and jotting down what I might want to say. I understood that it was important to know the language of so many of PEN’s members, especially when the Congress was in a French-speaking country. I didn’t do the same with Spanish because my Spanish was more remedial, but I had studied French at university and so had some base. French colleagues used to say, “Your accent is cute and you are fearless,” which I think was a nice way of saying you’re not very good, but at least you’re trying.

Before I came to the Dakar Congress, I had taken out my notebook from French lessons and copied on a single page the phrases I thought I might want to say at some point. When I arrived at the opening ceremony, I was seated on the dais along with Jiří, PEN’s Vice Presidents, the President of Senegalese PEN and the President of Senegal. I had not been informed that I was expected to give a speech, but my name, along with Jiří’s, was on the program. I knew Jiří didn’t speak French, and I felt it would be insulting for neither of us to speak in one of the languages of the country. That morning I’d tucked my sheet of phrases into my bag, and as I sat there, I glanced at the accumulation of sentences; they were a kind of speech so for the first few minutes I spoke in French then said, “Now I’d like to shift to English so I can speak better from my heart.” Everyone had translation equipment.

When the closing ceremonies arrived, the same situation arose. With the Prime Minister of Senegal also on the dais, I was again listed on the program to speak. However, this time Senegalese PEN had written remarks for me in French, and I stepped over to my nearby colleagues at French PEN to practice.

PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman addressing Assembly of Delegates at 73rd PEN Congress, July 2007.

To close out this final memory, I share here a portion of my report to the Congress. Each International Secretary and President and Board member and Staff member brings his/her talents, skills and affection to this organization which is held together in part by ideals and friendship. In marking progress, no one diminishes the work that came before. I continue to note in wonder the improbability of an organization of writers connected around the globe in 150 centers in more than 100 countries surviving for a century. With gratitude I recognize those who have come before and kept the organization together and those who come after and add to the bridges and structures or whatever metaphor suits at the time. Here is a brief summary of my journey those years as International Secretary:

As an organization we have grown in the past three years, both in numbers of centers, scope of activity, and size of the Secretariat. We have worked to strengthen the infrastructure of the London office so that it can better assist the centers and can coordinate the international work of PEN. We have put financial systems in place for budgeting and have expanded fundraising, and have established employment procedures and contracts for staff and transparent criteria for our own grant-making.

The Board, which now meets monthly by phone, has worked, along with the Staff and myself, in this process. I want to take this moment to thank the Board whose members work hard on your behalf and each of whom has always said yes when asked to take on a task. I’ve also had the pleasure of working with a wonderful staff, first Jane Spender, who has now retired and sends her best and with the highly qualified team of Caroline McCormick, Sara Whyatt and now Frank Geary and Karen Efford and newer members Tamsin Mitchell and Emily Bromfield…I want to thank former International Secretaries Alexandre Blokh and Terry Carlbom who have always been available when I’ve sought counsel. And I want to thank so many of you in the centers who have helped me in the work and my home center in America for sustained support. Finally we all want to thank Senegalese PEN for its work in putting on this Congress and all the African centers who participated in this effort.

To finance PEN’s growth we have raised funds from new funders and from existing funders, who have signed onto the expanded program for International PEN and have given us larger grants…

I’ve had the pleasure of working with and visiting many of you and your centers over the last three years…One of the greatest pleasures of working with International PEN has been developing friendships around the globe.

PEN is only as strong as its centers. We have been working through our regional program on a one-to-one basis with centers in Africa this year to develop strategic plans. Through the Board we have also been in touch with centers whom we have not heard from in long time to see if they still exist and to find out how we might help them. Through the workshops at the Congresses and in the consultations last year with the whole membership, we have developed for centers a guide to good governance which we will share later at this Congress. Most PEN centers already operate according to the principles of transparent membership criteria, regular elections, rotation in office, and governance by a constitution, but other centers need assistance in this area.

PEN began as a club of writers committed to the ideals which developed over the years. But a club does not mean that qualified writers should be kept out of the work of PEN or that PEN should be an exclusive Academy. There has always been the balancing of PEN as a club and PEN as a nongovernmental organization (an NGO.) Each center chooses its activities, but internationally, PEN operates as an NGO. That is why we have consultative status at the United Nations. Clubs do not receive this status. As an international organization we work to achieve goals related to civil society—the goals of promoting literature and defending freedom of expression. The work of International PEN, through its committees and through the centers and writers who chose to participate in the international work, serves these goals.

This year Caroline and I visited UNESCO several times and are happy to report that UNESCO officials are enthusiastically recommending PEN’s partnership under the framework agreement be renewed for another six-year period. They specifically praised PEN for its “significant modernization.”

At a PEN Congress in 1966 the Mexican novelist Carles Fuentes took note of “the improbable spectacle of 500 writers—conservatives, anarchists, communists, liberals, socialists—meeting not to underline their differences or to enumerate their dogmas, but to bear witness to the existence of a community of spirit while accepting diversity of interests.” That is still what PEN is and what PEN represents to the world.

The theme of this Congress—The Word, The World and Human Values—resonates and was chosen by PEN’s African centers. I am particularly honored to be finishing my term in Africa, for African literature and the literature of African American writers have had a significant influence on my own work as a writer. I’d like to end with a verse from Senegal’s great poet and first President and also International PEN Vice President Leopold Senghor, from his elegy written after the assassination of my countryman Martin Luther King. Senghor’s life offered a kind of bridge in the world. Through his life and his words, he showed how an individual and a writer can in fact enhance human values.

From Senghor’s “Elegy for Martin Luther King”:

“As the Reverend’s heart evaporated like incense and his soul

Flew like a diaphanous rising dove, I heard behind my left ear

The slow beating of the drum. The voice and its sharp breath close to

My cheek said: ‘Take up your pen and write, Son of the Lion.’

“And I saw a vision…”

You must read the poem to see the vision, but I can tell you it is a vision very much in the spirit of PEN.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 46: Wrapping Up

PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

After PEN’s Asia and Pacific Regional meeting in Hong Kong February 2007, I flew to Tokyo for a two-day visit with members of Japanese PEN, along with International PEN board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori. We met with Japan PEN’s board, and in the evening I shared a stage and conversation with Mr. Hisashi Inoue, chairman of Japan PEN and one of the country’s well-known playwrights. Part of our discussions explored the possibility of Japanese PEN hosting an International PEN Congress. Only once before, in 1984, was the World Congress held in Japan.

International PEN Board members Eric Lax and Takeaki Hori

Housed in an impressive building in Tokyo, Japan PEN was one of International PEN’s largest and most active centers with one of the more interesting histories. Founded in November 1935 on the eve of a tumultuous period in world affairs, Japan PEN members committed to the PEN ideals of freedom of expression and “one humanity living in peace in one world.” By 1935 Japan had left the League of Nations in the wake of the Manchurian Incident and was moving towards international isolation, a direction that concerned liberal literary figures and diplomats. In this climate International PEN in London, with support from leading novelists, poets and foreign literary figures, reached out and requested that writers in Japan form a PEN Club. Japan’s well-known novelist Toson Shimazaki served as the founding president. As suppression of free speech increased as war in the Pacific broke out and the Second World War advanced, Japanese PEN stayed in limited contact with International PEN in London and provided a unique portal to the world for its writers and citizens during that time.

Japan PEN members at PEN’s 71st Congress in Bled: Furukawa Taeko, Miyakawa Keiko and Yonehara Mari, along with Fawzia Assad (Suisse Romand PEN) Huguette de Broqueville (French PEN) and Celia Balcazar (Colombian PEN) and Takeaki Hori (PEN International Board & Japan PEN)

Personally, I remember the hospitality of Japan PEN members who took me out on the Ginza to toast my birthday as I rounded a decade. I had explained that I needed to fly home that evening, a day early to share the birthday. I still remember the glasses of pink champagne flowing up and down the Ginza, (though I was drinking sparkling water), as my own new decade was heralded, then flying halfway around the world and arriving in time to have another dinner that same night with my husband.

Three years later, in September 2010 Japan PEN hosted the 76th PEN International World Congress in Tokyo, one of PEN’s largest with representatives from 90 centers around the theme “The Environment and Literature—What Can Words Do?”

******