Posts Tagged ‘Russian PEN’

The Power of One: Dissent in Russia

With the war in the Ukraine front and center in the news, I can’t help thinking back to my Russian colleague from PEN, the General Secretary of Russian PEN Alexander Tkachenko, or Sascha as we called him. I wonder how he would have responded to what is unfolding. During his tenure at Russian PEN, he stood up and argued with Vladimir Putin face to face on behalf of Russian writers and resisted when the government tried to close down PEN in Russia.

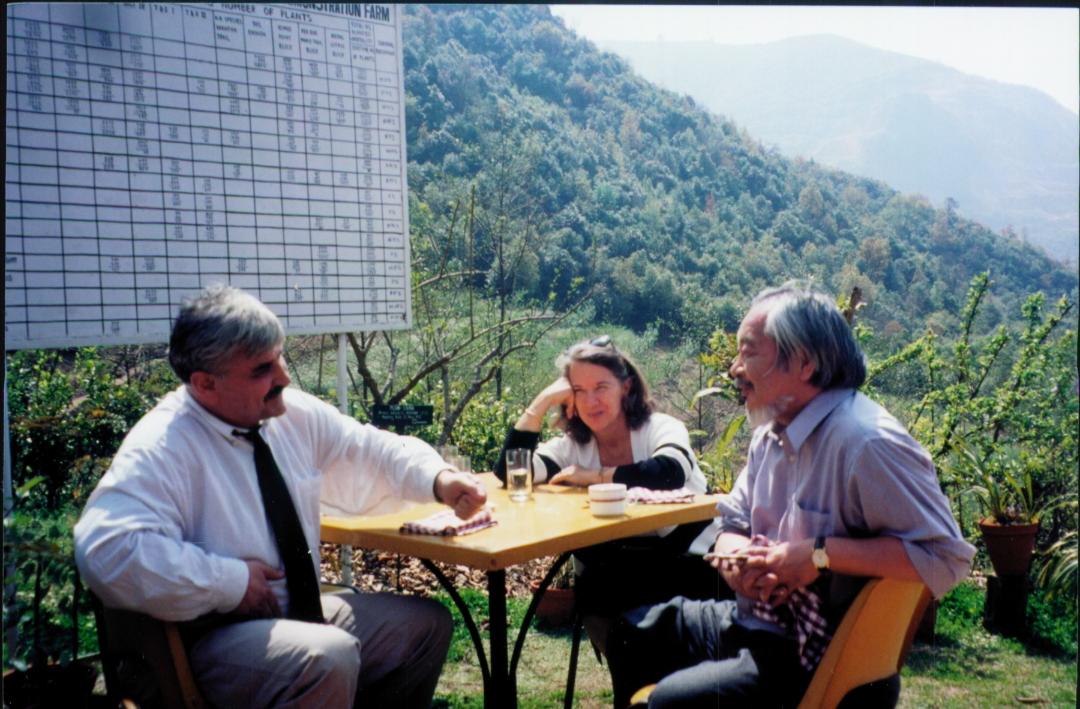

Sascha was complex—a former professional soccer player, a Tartar, son of the Crimea, a poet. Those who knew him may still hear his voice on the floor of PEN Congresses challenging his government’s imprisonment of writers, apologizing to new Afghan PEN delegates for his country’s incursion into their country, or remember Sascha swimming off the coast of Perth, Australia in spite of the signs warning of sharks or singing and reciting his poetry at the Writers in Prison Conference in Denmark, or strategizing with the Writers in Prison Committee in the hills of Nepal.

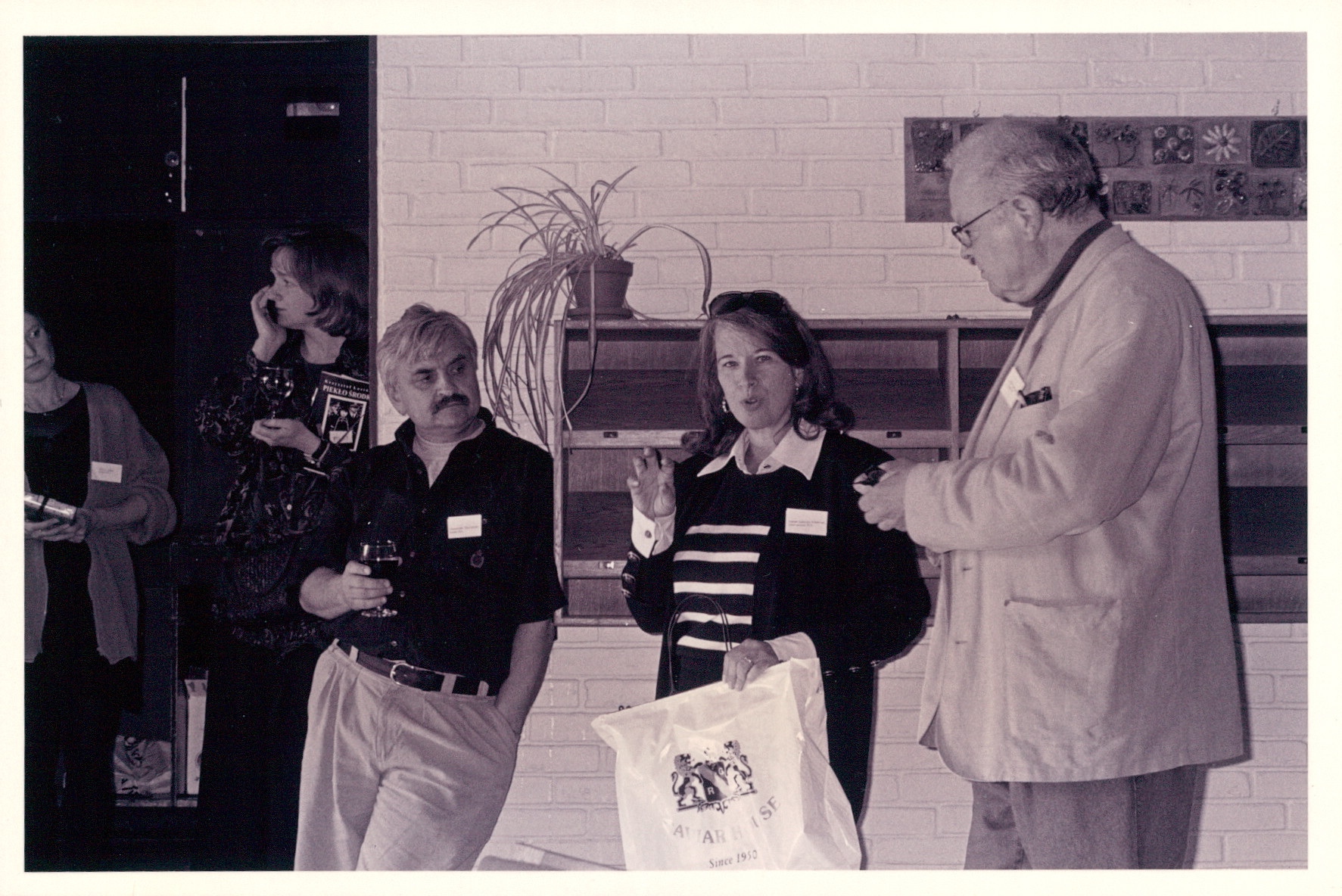

Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Chair of PEN International Writers in Prison Committee), and Niels Barfoed (Danish PEN) at the first Writers in Prison Committee Conference held in Helsingør, Denmark in 1996

Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (American PEN/PEN Int’l), Mitsakazu Shiboah (Japan PEN) at the 2000 Writers in Prison Committee meeting in Kathmandu, Nepal

When Sascha suddenly turned up dead in 2007 at age 63, we were all shocked. Some speculated perhaps he drank too much vodka; he had a heart condition. We accepted that it was “heart failure” though even at the time, the skeptical voice questioned whether there could have been foul play. As I witness now the carnage in the Ukraine and have since seen the incidents of murder and recently read accounts of those who have been eliminated in Russia in books such as Bill Browder’s Red Notice and the new Freezing Order, doubts again stir about Sascha’s sudden end. I wonder how he would have reacted to the drama playing out today and the closing down of any freedom of dissent in Russia. Today there are additional PEN Centers in Russia—PEN Moscow, PEN St. Petersburg, Tartar PEN, and writers I’m told have differing views among them. But Sascha I feel certain would have defended the right to dissent, to stand up for the freedom to live.

Below is the tribute I wrote at the time. I feel I am mourning Sascha all over again as we mourn the loss of the freedoms he and others struggled for, and we mourn the loss of this vision of a nation.

December 7, 2007

General Secretary of Russian PEN Alexander Tkachenko –Sascha as he is known to his friends—died this week, peacefully in his sleep, we are told. It is hard to imagine Sascha passing anywhere peacefully, certainly not from this world.

As Russian PEN’s General Secretary, this hearty man with salt and pepper hair and moustache, this former professional soccer player and respected poet campaigned fearlessly for writers threatened in Russia. He often stood his ground with officials, bureaucrats, the military and with Vladimir Putin himself. When Putin once visited the Russian PEN offices, Sascha challenged him directly on the rights of writers and freedom of expression in Russia.

Sascha traveled the huge expanse of Russia from one end to the other to lobby, to argue, to advocate on behalf of writers who faced imprisonment by the Russian state, writers such as Grigory Pasko, the journalist and poet who was arrested after reporting on Russia’s dumping of nuclear waste. He championed as well those in former regions of the Soviet Union, in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan. He also spoke out and represented the voice of Russian writers on behalf of imprisoned writers around the world.

Sascha served on the Board of International PEN and attended PEN conferences and Congresses for the past decade. My personal memories are many. I particularly remember standing side by side with Sascha at Istanbul University in 1997 surrounded by riot police as we addressed a crowd of thousands with a bull horn. We were the two representatives of PEN advocating for freedom for Turkish writers in prison.

When the Russian government threatened to close Russian PEN in 2006 because of alleged tax payments suddenly demanded, PEN centers around the world rallied to help. I was International Secretary of PEN at the time and able to meet with Sascha and members of Russian PEN in Moscow as these payments were secured. That meeting was also attended by Rakhim Esenov from Turkmenistan, an elderly former general whose novel had been banned and who had been imprisoned for his book allegedly being “historically inaccurate.” Only a week before American PEN had given Esenov its Freedom to Write Award in New York. He was on his way home through Moscow, where Sascha and Russian PEN offered additional moral support as he returned to face the threats of his government.Rally at Istanbul University [Includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Chair/American PEN), and Turkish Conference organizer Şanar Yurdatapan]

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (center), 2006

When I think of Sascha, I first hear his laughter and then his arguments, then his particular English; I see his hands waving as he talks, see him reluctant to yield a microphone until his point is made; I see him as he must have been as a young man blocking and running down the field as a soccer player, bobbing and weaving, pushing past those who would try to stop him as he drove to the goal. In his last decades that goal was getting writers out of prison. Sascha was an advocate we all would want on our side should we find ourselves threatened or in prison. He will be mourned and sorely missed.

His funeral is in his home village of Peredelkino December 10, Human Rights Day. He would have liked that framing of time on his passing, though he will not really pass; he will simply rest in our thoughts and rise in our thoughts when courage is called for and an advocate is needed. When a government acts as though it is more powerful than the individual, Sascha’s memory will remind us of the power of one. His voice continues through his writing, and the impact he has had on the lives of writers imprisoned continues.

—Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At the end of September 2005 a Danish newspaper published 12 editorial cartoons which depicted Mohammed in various poses as part of a debate over criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark objected, and by early 2006 protests, violent demonstrations and even riots erupted in Muslim areas around the world. The offense was the “blasphemy” of drawing Mohammed in the first place and the particular mockery of some of the depictions in the cartoons.

The uproar over the Jyllands-Posten Mohammed cartoons quickly drew PEN into the controversy, first through Danish PEN and then through the International PEN office and other PEN Centers. PEN included many Muslim members and numbers of centers in majority Muslim countries. All PEN members and centers endorse the ideals stated in the PEN Charter. However, the third and fourth articles of the Charter which addressed the situation, also at times appeared to contradict each other:

Article 3: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

Article 4: “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world toward a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restrain, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

PEN International Board and Staff 2006. L to R: Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Elizabeth Nordgren (Finish PEN), Jane Spender (Programs Director) Sara Whyatt (Writers in Prison Committee Director), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Karen Efford (Programs Officer), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International President), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Britta Junge-Pederson (Treasurer), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair), Chip Rolley (Search Committee Chair), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Peter Firkin (Centers Coordinator) [not pictured: Mohammed Magani (Algerian PEN), Karin Clark (WiPC Chair), Kata Kulavkova ( Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair)

Peace Committee program 2006. Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Veno Taufer (Peace Committee Chair)

At the Peace Committee conference that April, I observed, “The Charter of PEN asserts values that can appear contradictory, but represent the dialectic upon which free societies operate and tolerate competing ideas…In our 85th year, International PEN still represents that longing for a world in which people communicate and respect differences, share culture and literature, and battle ideas but not each other.”

The Danish cartoon controversy led off 2006. For me, the PEN year also included attending the conferences of three of PEN’s four standing committees—the Peace Committee in Bled, Slovenia, Writers in Prison Committee in Istanbul, Turkey (PEN Journey 35) and Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee in Ohrid, Macedonia (PEN Journey 39)—and in May the 72nd PEN World Congress in Berlin, and later a Danish Conference on the Middle East in Copenhagen, the Gothenburg Book Fair in Sweden, a PAN Africa Conference in Dakar, Senegal and a trip to Moscow, where I went to watch my oldest son compete in the European Wrestling Championships and visited Russian PEN on a mission.

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including Alexander Tkachenko, General Secretary, 2006

To Moscow I took just under $10,000 raised by PEN centers and buried in my luggage to help the Russian PEN Center. Vladimir Putin and the Russian government had begun to crackdown on nongovernmental organizations with ties to other countries. One of their first targets was Russian PEN which had opposed the legislation restricting nongovernmental organizations. At the time I was also on the board of Human Rights Watch, a larger organization which was watching closely what was happening to PEN. The government’s attack on Russian PEN came in the form of a freeze on all assets for failure to pay a land tax. Russian PEN argued that it was a legal tenant where it had been conducting business and was not liable for the tax on the land, but the tax office refused to drop the charges. The government threatened to close PEN and take away its office if the money wasn’t paid. An appeal had gone out to PEN’s other centers, which had responded from around the globe not only with protests to Moscow but also with funds for Russian PEN.

I brought in funds just under the amount I would have had to declare. During the wrestling tournament I met with Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko, the General Secretary of Russian PEN, and delivered to him the donation, and he gave me a receipt. The funds stayed off the crisis for then. Charges were dropped. A Russian Minister said, “I don’t understand. I was getting letters from as far away as Argentina!” Sascha answered him: “That is the kind of organization we are.” PEN continued to operate.

In Moscow I also met with Russian PEN members as well as with Turkmen author Rakhim Esenov, who was visiting Russian PEN. I had met Esenov a few weeks before in New York where he had won PEN America’s Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write award. In Turkmenistan Esenov had been charged with “inciting social, national and religious hatred using the mass media” because of characters in his novel The Crowned Wanderer. Set in the 16th century Mogul Empire, the story focused on a poet/philosopher/army general who was said to have saved Turkmenistan from fragmentation. The president of Turkmenistan Saparmurad Niyazov banned the book for portraying the main character as a Shia rather than a Sunni Muslim, and he imprisoned Esenov for several months. I still have the massive Russian language volume he shared with me, a work that had taken him years to write.

L to R: Russian PEN General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko and Russian PEN member outside Russian PEN office in Moscow and Rakhim Esenov, author of The Crowned Wander and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), 2006

At the Peace Committee conference earlier that month I’d presented a paper on the conference theme “The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World,” a broad and challenging topic which had inspired me to peer both backward and forward.

Below is the beginning of that paper with a link to the rest:

My first memory of a PEN meeting was sitting in someone’s living room in Los Angles writing postcards to free Wei Jingsheng from prison in China. At the time in the 1980’s he’d already been in prison several years of a fifteen-year sentence. I had no idea who this writer was thousands of miles away. I barely knew the other writers in that living room. On the coffee table would have been PEN’s Case List, which at the time was white sheets of paper stapled together.

We wrote and stamped our post cards for Wei and other writers that afternoon. I’m sure we were provided with background on his case. I pictured these cards fluttering into a jail somewhere in China and perhaps even into the cell of this stranger to let him know we had taken note of him and cared what happened. Looking back on the blue-sky afternoon as we sipped sodas and ate crackers and cheese, I see our act as a bit fleeting, an effort to imagine the fate of another writer who didn’t have our freedom to write and speak…[continue reading here]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN Journey 17: Gathering in Helsingør

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

What I remember most about the gathering of colleagues from 28 countries—31 PEN centers—51 of us in all at the first Writers in Prison Committee conference in 1996 was the seriousness of purpose and intellect during the day and the fun and talent in the evenings.

Hosted by Danish PEN, writers from every continent gathered at a university in Helsingør—known in English as Elsinore, the home of Shakespeare’s Hamlet—where we met in workshops and ensemble during the day to shape and refine our work on behalf of writers and freedom of expression around the world. But in the evening we were at a small university in a small city without transportation or distraction so we entertained ourselves. Each delegate displayed talents—from poetry reading to song to dance to musical performances.

As Chair of the WiPC gathering, I’d brought none of my own writing to read and was left to exhibit meager other talent which consisted of playing a few opening bars of Für Elise on the piano and whistling tunes with my far more talented Danish and Russian colleagues. Archana Singh Karki from Nepal in flowing red dress entertained with her graceful dance; Siobhan Dowd, our Irish former WiPC director and Freedom of Expression director at American PEN, silenced us with her soulful Irish folk songs, sung acapella; Sascha, Russian PEN’s General Secretary, not only whistled robustly but recited his poetry, which I was told I should be glad I didn’t understand with its bawdy content; Sam Mbure from Kenya and Turkish/English novelist Moris Farhi also read and recited work. PEN International President Ronald Harwood joined the discussions in the day and was audience in the evening. I don’t recall if Ronnie offered his own work, but we all bonded in our mission and in our support for the talent in the room.

Entertainment in the evening: From the top left—Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Chair of WiPC)in a whistling song; Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East) accompanying Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN) in dance; Siobhan Dowd (at piano—English & American PEN) with Moris Farhi (reading—English PEN); Sam Mbure (reciting—Kenyan PEN); Niels Barfoed (reading—Danish PEN)

During the three days, we fine-tuned our methods of working on and campaigning for our main cases, those writers who were imprisoned, attacked or threatened because of their writing, often their nonviolent voice of protest against authoritarian regimes. We considered PEN’s decision-making on borderline cases such as those which included drug charges, advocacy of violence, pornography, hate speech, terrorism. These were not categories we normally took on as cases. We discussed when we might take up such a case or assign them to investigation or judicial concern. We laid the groundwork for more joint actions among centers and other organizations such as the U.N., OSCE and IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.

Round Table of the WiPC conference which included delegates from PEN centers in Switzerland, Jerusalem, Denmark, England, Mexico, Portugal, America, Norway, Czech Republic, Ghana, Canada, Australia (Melbourne and Sydney), Portugal, Finland, Nepal, Scotland, Malawi, Kenya, Ghana, Croatia, Slovakia, Sweden, Spain, Austria, Japan, Germany, Russia, Poland, Netherlands

With PEN’s WiPC staff Sara Whyatt and Mandy Garner, we set out a campaign calendar for the year, beginning with Turkey in May; China in June; Myanmar in July; Guatemala in September; Vietnam in October; Nigeria in November; Human Rights Day focus in December; Cuba in January; Rushdie and Fatwa and Iran in February; United Nations Commission on Human Rights lobbying in February/March and a return to China during the Chinese New Year in February/March; International Women’s Day in March and World Press Freedom Day in May. This campaign calendar meant that the London office would send information each month related to these foci, and PEN centers would plan programs if the campaign fit their work and the cases they had taken on.

We discussed the elements of successful missions to troubled areas and what future missions should be considered. In 1997 PEN International and Danish PEN sent representatives on a quiet mission to Cuba. We also strategized on the effect of writers observing trials in certain countries, particularly in Turkey.

Working session on Turkey Campaign at at WiPC conference: L to R: Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN), Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East), Robin Jones (WIPC staff), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair), Ronald Harwood (PEN International President)

During the conference a request came for members of PEN to sign on individually and en mass as publishers of a book in Turkey which republished an article by the famed Turkish novelist Yaşar Kemal, along with articles by other Turkish writers who were in prison because of their writing. Kemal had recently been charged because of an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel about the Kurds. The organizer in Turkey had gathered hundreds of Turkish writers, publishers, artists, and actors to sign on as publishers. They wanted to present the book and the list of hundreds of publishers to challenge the courts to bring charges against everyone. Many of us agreed to participate. This act launched a campaign in Turkey and a mission later in 1997. (Blog to come.) The independent Turkish Freedom of Expression Initiative has since gathered biennially for the last 23 years. For this kind of joint action PEN was primed to cooperate.

Finally in Helsingør the Writers in Prison Committee took a step towards opening up the election process for the WiPC Chair. My term was due to expire at the fall 1996 Congress in Guadalajara. We decided to select a nominating committee from members to find candidate(s) for the next chair rather than have the post appointed by the Secretariat in London. That process was later replicated in other elections in PEN and is standard procedure today.

Workshop: From left includes: Neils Barfoed (Danish PEN), Lady Diamond (Ghana PEN), Moris Farhi (English PEN), Sara Whyatt (WiPC Programme Director), Mandy Garner (WiPC researcher), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair at front)

Helsingør was a fitting venue for the first WiPC Conference, not only because of its literary credentials with the Kronborg Castle where most of Shakespeare’s Hamlet takes place, but also because of its historic legacy in World War II. Helsingør was one of the most important transport points for the rescue of Denmark’s Jews. A few days before Hitler had ordered that the Danish Jews were to be arrested and deported to concentration camps October 2, 1943, one of the Nazi diplomatic attaches who’d received word in advance shared the information with the Jewish community leaders. Using the name Elsinore Sewing Club, the Jewish leaders communicated with the population, and the Danes moved the Jews away from Copenhagen to Helsingør, just two miles across the straights to neutral Sweden. The Danish citizens hid their fellow Jewish citizens until they could get onto fishing boats, pleasure boats and ferry boats and escape over a period of three nights. The Danes managed to smuggle the majority of its Jewish citizens—over 7200 Jews and 680 non-Jews—across the water to safety.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 18: Picasso Club and Other Transitions in Guadalajara

PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I have been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions, including as Vice President, International Secretary and Chair of International PEN’S Writers in Prison Committee. With memories stirring and file drawers bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. In digestible portions I will recount moments and hope this personal PEN journey may be of interest.

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.

In those days PEN had close ties with UNESCO, and attending a PEN Congress was like visiting a mini U.N. Assembly. Delegates sat at tables with name tags of their countries in front of them. Action was taken by resolutions which were debated and discussed and then sent to the International Secretariat and back to the Centers for implementation. At the time PEN operated with three standing Committees, the largest of which was the Writers in Prison Committee focused on human rights and freedom of expression. The other two were the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and the Peace Committee. Soon, in 1991, a fourth—the Women’s Committee—would be added. At parallel and separate sessions to the business of the Assembly of Delegates, literary sessions explored the theme of the Congress.

PEN USA West was particularly active in the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) where we advocated for our “adopted/honorary” members, most prominent for us at that moment was Wei Jingsheng in China. We had drafted and brought to the Congress a resolution, noting that China had recently released numbers of individuals imprisoned during the Democracy Movement, but Wei Jingsheng had not been among them and had not been heard from. We addressed an appeal to the People’s Republic of China to give information on the condition and whereabouts of Wei Jingsheng and to release him.

Before we spoke to this resolution on the floor of the Assembly, we met with the delegate of the China Center. The origins of this center was a bit of a mystery since it was one of the few centers that defended its government’s actions rather than PEN’s principles. I still recall the delegate with thick black hair, square face, stern visage and black horn-rimmed glasses, though this last detail may be an embellishment. He argued with me that Wei Jingsheng was an electrician, not a writer, that he had simply written graffiti on a wall, but that he had committed a crime by sharing “secrets” with western press.

The Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee Thomas von Vegesack, a Swedish publisher, arranged for the celebrated Chinese poet Bei Dao, a guest of the Congress, to speak in support of the PEN USA West resolution. The delegate from Taipei PEN stood next to Bei Dao and translated his words which contradicted the China delegate. Bei Dao noted that Wei Jingsheng had been in prison ten years already, having been arrested when he was 28-years-old. He had already published his autobiography and 20 articles and for years had been editor of the magazine SEARCH. In his posting on the Democracy Wall and in his essay “The Fifth Modernization,” Wei had suggested that democracy should be added as a fifth modernization to Deng Xiaoping’s four modernizations. “This shows that Wei Jingsheng’s status as a writer can’t be questioned,” Bei Dao said. I still remember that moment of Bei Dao addressing the Assembly and his country man with a Taiwanese writer translating. For me it demonstrated PEN in action.

In Beijing at that time thousands of students and citizens were protesting in Tiananmen Square.

PEN Center USA West’s resolution passed. The China Center and Shanghai Chinese Center refused to accept the resolution. The Maastricht Congress was the last PEN Congress they attended for over twenty years.

In the months preceding the gathering in Maastricht International PEN Secretary Alexander Blokh, International President Francis King and WiPC Chair Thomas von Vegesack had visited Moscow where the groundwork was laid to bring Russian writers into PEN with a Center independent of the Soviet Writers Union.

Twenty-two years before, Arthur Miller, International PEN President, had also traveled to Moscow at the invitation of Soviet writers who wanted to start a PEN center.

In 1967 Miller met with the head of the Writers’ Union and recounted in his autobiography:

At last Surkov said flatly, “Soviet writers want to join PEN….”

“I couldn’t be happier,” I said. “We would welcome you in PEN.”

“We have one problem,” Surkov said, “but it can be resolved easily.”

“What is the problem?”

“The PEN Constitution…”

The PEN Constitution and the PEN Charter obliged members to commit to the principles of freedom of expression and to oppose censorship at home and abroad. Miller concluded that the principles of PEN and those of the Soviet writers were too far apart. For the next twenty years PEN instead defended and assisted dissident Soviet writers.

At the Maastricht Congress Russian writers, including Andrei Bitov and Anatoly Rybakov attended as observers in order to propose a Russian PEN Center. Rybakov (author of Children of the Arbat) told the Assembly that writers had “endured half a century of non-democratic government and had lived in a dehumanized and single-minded state.” He said, “Literature could be influential in the fight against bureaucracy and the promotion of the understanding between nations and cultures. Now Russian writers want to join PEN, the principles and ideals of which they fully shared, and the responsibilities of belonging to which they recognized…and hoped for the sympathy of the members of PEN.”

The delegates unanimously elected Russian PEN to join the Assembly. In the 1990’s and until he passed away in 2007, one of the most outspoken advocates for free expression in Russia was poet and General Secretary of Russian PEN, Alexander Tkachenko. (Working with Sascha, as he was called, will be included in future blog posts.)

Polish PEN was also reinstated at the Maastricht Congress. After seven years of “severe restrictions and false accusations by the Government which had resulted in their becoming dormant,” the Polish delegate said they were finally able to resume normal activity in full harmony with PEN’s Charter. “I must stress here that our victory we owe in great part to the firm and unbending attitude of International P.E.N. and to almost unanimous solidarity of the delegates from countries all over the world.”

At the Congress PEN USA West, American PEN, Canadian PEN and Polish PEN presented a resolution on Czechoslovakia, calling for the government to cease the recent campaign against writers and to release Vaclav Havel and all writers imprisoned. The Assembly recommended that the International PEN President and International Secretary get permission from Czech authorities to visit Vaclav Havel in prison. Two weeks after the Congress Vaclav Havel was released. In December of 1989 Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the communist regime. In 1994, President Havel, along with other freed dissident writers, greeted PEN members at the 61st PEN Congress in Prague.

Also at the Maastricht Congress was an election for the new President of International PEN. Noted Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stood as a candidate, supported by our two American Centers, Scandinavian centers, PEN Canada, English PEN and others, but Achebe was relatively new to PEN, and at the time there were only a limited number of African centers. Achebe lost by a few votes to the French writer Rene Tavernier, who passed away six months later.

Achebe admitted that he was not as familiar with PEN but said that if the organization had wanted him as President he had been persuaded that “it would be exciting.” He noted the world was very large and very complex. He hoped that in the years to come the voices of those other people would be heard more and more in PEN.

Our delegation had the pleasure of having dinner with Achebe in a castle in Maastricht which had a gourmet restaurant that served multiple courses with tiny portions. The small dinner, which also included the East German delegate and I think fellow Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta and an American PEN member, lasted over three hours. I’m told when Achebe left, he asked his cab driver if he had any bread in his house because he was still hungry. When I saw Achebe a few times in the years following, he always remembered that dinner.

At the Maastricht Congress two new Africa Centers were elected: Nigeria, represented by Achebe, and Guinea. The election of these centers signaled a growing presence of PEN in Africa. Today PEN has 27 African centers.

A few weeks after we returned from the Congress to Los Angeles, tanks entered Tiananmen Square. Hundreds of citizens, including writers, were arrested and killed. One of my first thoughts was, what will happen to Bei Dao, but fortunately he hadn’t yet returned to China. Our small PEN office started receiving faxes from London with dozens of names in Chinese, and we and PEN Centers around the globe began writing and translating those names and mounting a global protest. Among those on the lists I am sure, though I didn’t know him at the time, was Liu Xiaobo, who was instrumental in helping protect the students and in clearing the square.

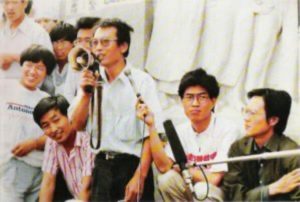

Tiananmen Square. June 4th, 1989. © 1989 Stuart Franklin/MAGNUM

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Twenty years later Liu Xiaobo would be a founding member and President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He would also later help draft and circulate the document Charter 08, patterned after the Czechoslovak writers’ document Charter 77, calling for democratic change in China. In 2009 Liu Xiaobo was again arrested and imprisoned. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in prison in 2017.

The opening of the world to democracy and freedom which we glimpsed and hoped for and which seemed imminent in 1989 appears less certain now.

Today, June 3-4, 2019 memorializes the thirtieth anniversary of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square. During the years after Tiananmen when Liu Xiaobo and others were in prison I chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. But that is a story to come…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move West to East

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International was started modestly almost 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catherine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others conceived that if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, at least among writers of Europe. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace.

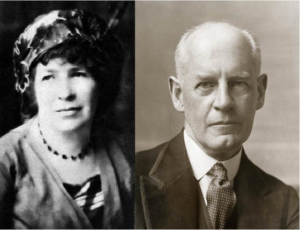

Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN spread quickly, and clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. Members of PEN began gathering at least once a year in a general meeting. A Charter developed to focus the ideas that bound everyone. In the 1930s with the rise of Hitler, PEN defended the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work. PEN’s Charter, which developed over a decade, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in over 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia, other countries in the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar. A PEN center is also a refuge for writers in certain countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

As part of PEN’s Centennial celebrations, Centers and leadership at PEN International have been asked to share archives for a website that will launch in 2021. As I dug through my sizeable files of PEN papers, I came across this speech below which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN Diyarbakir Conference, March 2005

This talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is stirring anew. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King and others have been quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through 141 centers in 99 countries. They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see this ancient city for himself, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together. –Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International