Posts Tagged ‘Jiri Grusa’

PEN Journey 46: Wrapping Up

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I finished my term as International Secretary of PEN July 2007 at PEN’s 73rd World Congress in Dakar, Senegal. I handed over the responsibility to my longtime colleague Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) who would continue to work with the Board, the Executive Director Caroline McCormick, new Treasurer Eric Lax and President Jiří Gruša. We had executed many changes in the last three years, and those who had been involved were continuing and active both in the international leadership and in the PEN centers.

Before the Congress, the staff and PEN members gave me a farewell party at PEN International’s relatively new London headquarters on High Holborn. PEN is about people, and I’d been fortunate to work over many decades with dozens of talented writers who were also competent in organizational work, friends from around the globe who remain friends today.

PEN International Farewell gathering in London 2007 with friends and staff, including Caroline McCormick, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Jane Spender, Sara Whyatt, Moris Farhi, Peter Firkin, Eugene Schoulgin, Frank Geary, Emily Bromfield, Mitch Albert, Mandy Garner.

As a Vice President, I would continue to work, write appeal letters to governments for the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC)’s RAN (Rapid Action Network) cases, speak when asked and hold meetings in Washington when asked, but I could return to being a writer. American PEN’s Executive Director Michael Roberts asked me to join American PEN’s board. I demurred and said I needed a break, but he and others urged me so in 2008 I joined the board of PEN America but worked at a far less intense pace for the next six years. When American PEN’s new Executive Director Suzanne Nossel came on, I was asked to extend for an additional year as a Vice President while she oriented to PEN’s international work. It is difficult to step away from PEN though most who are engaged find they must for a time, though not too far away.

As I left the historic Senegal Congress that July 2007, I boarded a plane and flew out over the Atlantic to Italy where I met up with my husband by a lake in one of our favorite spots for a vacation. He had patiently waited those three years as I spent 10-15 days a month on the road. In the first week without PEN’s emails and phone calls and conferences, we talked; I wrote, and I read four books in six days.

Back home I soon realized I needed to join the 21st century as a writer. At PEN we had begun to use some tools of social media in publicizing cases of writers under threat, but I hadn’t engaged personally. I remember sitting with a group of women writers in Washington, DC, many younger than me, who were talking about their websites and blogs and Twitter, and Facebook. In 2007 writers having URLs, Twitter handles, Facebook pages was relatively new. Twitter had only launched the year before, and though blogs had been around for a few years, I had never written one. Facebook seemed an odd medium, also only a few years old. I was of the “private” generation; we were not prone to sharing our activities and feelings on a “social” platform. Those of us who’d been journalists were used to having to condense stories, but never to 140 characters which Twitter demanded. We were in a new communications age, and I needed to understand and at least to put a toe in the water, even if I didn’t jump fully in.

Encouraged by friends and agent, I set up a website. The developer urged me to blog. I didn’t want to blog, I explained. I wanted to write fiction and occasional journalism, but I agreed to post a blog once a month. I have done so for over ten years now. Often when I considered what was worth writing about each month, I found myself reflecting on work with PEN. When asked to write about PEN’s history as I’d witnessed it in anticipation of the Centennial, I reasoned I could post twice a month. That seemed a reasonable way to get through PEN’s history year by year. A serial blog. I have sped up the pace since Covid locked us all into our homes and travel has halted. I have now come to an end of this particular PEN Journey though I will write an introduction. I will also reference links to those blog posts I wrote after 2007 when I continued to work with PEN.

In this final post, I want to review a few areas of PEN International I feel I haven’t explored sufficiently, and I want to give a quick view forward of what and who came next.

In Journey’s 7, 8, 22, 25, 26, I touched on the work of the PEN Emergency Fund. I want to highlight that here. Founded in 1971 by Dutch Writer A. (Bob) den Doolaard who had an active role with PEN International, the PEN Emergency Fund fulfilled a missing link in PEN’s work. Doolaard noted that PEN had no mechanism to grant material aid to writers, especially those under threat who had to flee their countries so he and Dutch PEN set up the aid fund based in the Netherlands, operated under Dutch law. The PEN Emergency Fund gives a one-time grant to writers in dire circumstances and is able to act quickly. Over the years PEN’s Emergency Fund has provided rapid support for writers on every continent, especially those in Eastern Europe during the Communist era and those in the Balkans War in the 1990s and also to persecuted writers in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Every year dozens of writers have been helped with grants that have bridged to longer term answers. The Fund operates in close collaboration with PEN International whose professionals furnish the Fund with information and with the PEN centers and members who have contributed to the Fund. I’ve had the privilege of serving on the PEN Emergency Fund Advisory Board for a number of years.

Prizes: As a literary organization, PEN through its centers awards numbers of literary awards, but only a few literary prizes have been awarded by PEN International. Over the years the idea of a PEN International Prize for Literature or even for Peace has arisen. When I first took on the position of International Secretary, we were approached by a donor offering to give PEN $100,000 for the PEN International Prize for Peace. Well-meaning though the donor was, it quickly became clear that PEN International could not accept. The donor already had his first winner in mind—Bono. We explained that any prize would have to be independently judged with established criteria and nominating processes, and in order for PEN to give an annual prize, we would need to have a substantial financial commitment in an account to assure we could afford the prize each year as well as the cost of the judging and ceremony. We named the figure. The discussions broke off though the donor, I think, did find another way to give his prize though not through PEN.

Chimamanda Adichie, PEN David T. Wong International Short Story Prize winner.

The biennial PEN David T. Wong International Short Story Prize did come into being for a time, with a much more modest monetary award for a new writer, open to nominations by all PEN Centers and run by International PEN Foundation’s Gilly Vincent, who later became General Secretary of English PEN. Gilly was a pro and lined up well-qualified writers as judges. The nominations came in from PEN Centers around the world and the winner was often celebrated at PEN’s Congress. One of the first winners for 2002-2003 was a young Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie, who won for her short story “One Half of the Yellow Sun,” submitted by her local PEN Center USA West. The story went on to become the celebrated novel by the same name, and she went on to win wide international acclaim for that and other books. The PEN David T. Wong Prize was one of the first international recognition of her as a writer. The judges for 2003 were William Trevor, Michele Roberts and J.M. Coetzee who won the Nobel Prize for Literature later that year. The 2001 prize had been won by Rachel Seifert, who went on to have her first novel short-listed for Booker Prize.

PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, the PEN Emergency Fund and Oxfam Novib each year do give the Oxfam Novib/PEN International Free Expression Award to writers who work for freedom of expression in the face of persecution. The award is given to writers and journalists committed to free speech despite the danger to their own lives.

Turkey visit—on the roof with Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Carl Morten and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN)

Many other literary awards and literary festivals are hosted by PEN’s centers around the world. I had the pleasure of visiting a number of those, including in Croatia and in Turkey, hosted by the PEN centers.

There are many aspects of PEN’s work I’ve touched on but not explored fully such as the formation of a PEN center, which technically can occur when 20 reputable writers get together and petition the International office. There is a limit of five centers per country; most countries have fewer, and many countries have only one center. The rationale for additional centers has been to reflect linguistic diversity in a country. For instance, Switzerland has French, German, Italian, and Esperanto centers, or to facilitate participation when the land mass is large. The U.S. used to have two centers, one based in New York and one in Los Angeles, but in the past years, the two centers have merged into one PEN America. In Canada where there is both large land mass and diverse languages PEN has two centers—PEN Canada based in Toronto essentially uses English as the primary language and Quebecois PEN uses French. In some countries there are many, many languages as in India, which also has a large landscape and has the All-India Center in Bombay and the PEN Delhi Center. The rationale depends largely on the ambition and needs of the writers on the ground. Often a center will form branches within a country to provide the services and community for writers.

One document I did not include in an earlier post was the rationale from PEN International Vice President and Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer regarding the formation and naming of centers as related to a petition from writers in South Africa to form an Afrikaans Center. I’ve copied it here because it was from one of PEN’s eminent and active members and because it articulated ongoing questions in PEN. Gordimer’s argument did not prevail at the Berlin Congress in 2006 where an Afrikaans Center, not a Pretoria Center, was voted in though the center is based in Pretoria. The reasoning nonetheless is worth considering. The dynamics are ongoing in a number of countries and will likely continue as new centers are added or removed when they grow inactive.

Nadine Gordimer: “Let me make it clear. My objection to the formation of an Afrikaans language PEN club has no significance whatever of any kind of prejudice against my brother and sister South Africans, who are Afrikaans speakers and writers just as I am an English-speaking writer. We have eleven languages in our country. I should have exactly the same objection to the formation of an isiZulu or isiXhosa Club. We cannot have separate-but-equal (shades of apartheid) Clubs for every language, even though most of which have the strong linguistic claim of ante-dating colonially imported English and colonially created Afrikaans. I support a vigorous and linguistically open South African PEN Club, to have local representation in each region, with membership actively pursued among writers in whatever South African languages are theirs. Only such a chapter could have the strength to fulfil our needs…Historic-culturally determined circumstances give us both the necessity to overcome them and the fine opportunity to make full use of them, for our writers and our poly-literature.”

PEN is a breathing, living organization whose main body has been working around the world for a century with new members and centers joining every year as other centers at times have fallen dormant or closed. It is a fellowship of writers, of citizens in civil society holding watch over freedom of expression, linguistic diversity, over literature, and over the imagination and art by which societies flourish. Particular issues and threats change according to the times. PEN declares itself an apolitical organization, yet it is an organization whose central principle and commitment to freedom of expression sets it in the fray of politics since an early warning of a society descending into authoritarianism is the arrest of its writers and the closing down of space for free expression.

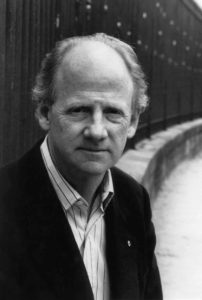

Changes in PEN leadership internationally and in centers effect the organization, but the Charter holds the whole body together. The leadership of PEN International used to reside in the President, the International Secretary and the Treasurer as the Executive, which represented the Centers’ Assembly of Delegates between two annual Congresses. The narrative of this PEN Journey has shown the change in the organization and its governance as it has grown and the world in which it operated has altered. PEN International has more than doubled in size over the last three decades to 155 centers in more than 100 countries. It now holds only one Congress a year, and the leadership is a partnership among the President, the International Secretary, the Treasurer, and an elected 7-member Board representing the Centers. Work is facilitated by an Executive Director, a position first hired in 2005, who heads the staff. Depending on the skills and experience and personality of each, the dynamic changes. In my term, I tended to be hands-on as an International Secretary. The President Jiří Gruša with whom I served was engaged as the Director of a Diplomatic Academy and had not been very active in PEN before he took the role of President. I would check in with Jiří before each monthly board meeting, explain the agenda as I saw it, ask if he wanted to add or change any items and if he wanted to attend. Jiří, a former prisoner of conscience, had lived the principles of PEN, understood them and with experience, knowledge and wit was an authentic voice on the international stage. But the day-to-day decision-making and running of the organization he largely left to me and then with the first Executive Director, the Board and the staff.

Jennifer Clement, PEN International President 2015-2021

John Ralson Saul, PEN International President 2009-2015

Jiří’s successor John Ralston Saul, former President of PEN Canada, had been a long time PEN member, active in the organization with experience in governing. He took on a much more active role as President, working with International Secretary Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) and then International Secretary Hori Takeaki (Japan PEN). John traveled the globe visiting PEN centers and government officials and taking on the issues of his period. After John, PEN elected its first woman President Jennifer Clement, former President of PEN Mexico, who took on the work, along with a special focus on the issues of women globally. She spearheaded, along with PEN’s Women Writers Committee, a Women’s Manifesto and later an Imagination Manifesto and will serve until the end of the Centenary Congress in England in 2021. Kätlin Kaldmaa (Estonian PEN) has served as International Secretary during this time along with longtime PEN member Carles Torner as Executive Director.

Unfortunately over the years as PEN’s website has been upgraded, the content has not always been exported so many of the documents and speeches and records have not followed into the digital universe. The narrative is carried in paper files which overflow in my basement and even more in PEN’s and in the memories of PEN members. My own PEN Journey has been an effort to record some of the history and offer a continuity of narrative during a particular period, through the eyes of one PEN member who has had the privilege and pleasure of standing up close for part of that history. I’ve tried to render the direction and actions. The flaws, the missteps of people, including myself, I’ve also witnessed but have largely left to the side in this narrative. My purpose has not been to be a critic nor a hagiographer, nor a novelist, but a reporter, recording the actions and the journey with a touch of personal memoir.

I will leave this journey by quoting from PEN’s Democracy of the Imagination Manifesto, unanimously passed at the 85th PEN World Congress in Manila, Philippines, October 2019:

The opening of the PEN International Charter states that literature knows no frontiers. This speaks to both real and, no less importantly, those imagined.

PEN stands against notions of national and cultural purity that seek to stop people from listening, reading and learning from each other. One of the most treacherous forms of censorship is self-censorship —where walls are built around the imagination and often raised from fear of attack.

PEN believes the imagination allows writers and readers to transcend their own place in the world to include the ideas of others. This place for some writers has been prison where the imagination has meant interior freedom and, often, survival.

The imagination is the territory of all discovery as ideas come into being as one creates them. It is often in the confluence of contradiction, found in metaphor and simile, where the most profound human experiences reside.

For almost 100 years PEN has stood for freedom of expression. PEN also stands for, and believes in, the freedom of the empathetic imagination while recognizing that many have not been the ones to tell their own stories.

PEN INTERNATIONAL UPHOLDS THE FOLLOWING PRINCIPLES:

- We defend the imagination and believe it to be as free as dreams.

- We recognize and seek to counter the limits faced by so many in telling their own stories.

- We believe the imagination accesses all human experience, and reject restrictions of time, place, or origin.

- We know attempts to control the imagination may lead to xenophobia, hatred and division.

- Literature crosses all real and imagined frontiers and is always in the realm of the universal.

Next and final installment of PEN Journey: Introduction—the Curtain Rises

Links below are to blog posts mentioning PEN after 2007. I was not writing official reports of Congresses or WiPC conferences or other events, but reflecting on PEN’s work, cases and the impact of ideas in my own monthly posts, some of which I used in writing this PEN Journey:

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate

March 31, 2020

Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

March 20, 2019

Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression

May 23, 2018

Women’s Voices Rising (Women’s Manifesto)

February 28, 2018

Liu Xiaobo: On the Front Line of Ideas

December 7, 2017

Reclaiming Truth In Times Of Propaganda (83rd PEN Congress in Lviv, Ukraine)

September 28, 2017

“Finding Room for Common Ground: No Enemies, No Hatred”

September 8, 2017

In Turkey, a show of solidarity with writers behind bars (PEN Turkey Mission)

February 3, 2017

Power on Loan

January 23, 2017

Hope for Songs Not Prison in 2017

December 27, 2016

Building Literary Bridges: Past and Present (82nd PEN Congress in Ourense, Spain)

October 3, 2016

Call for Help inside Iran’s Evin Prison

May 23, 2016

Spring and Release

March 18, 2016

View on the Bosporus: Rights in Retreat

January 29, 2016

Democracy in Africa: Who Can Chat with Kabila?

November 30, 2015

Life instead of Death…Rationality instead of Ignorance (81st PEN Congress in Quebec, Canada)

October 23, 2015

What Are You Not Reading This Summer? (WiPC Conference in Amsterdam)

June 11, 2015

Times and Tides

November 14, 2014

PEN on the Plains of Central Asia (80th PEN Congress in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan)

October 7, 2014

Poets, Pardons and Ramadan

August 2, 2014

Women’s Progress: The Power of a Bridge…and a Double Yellow Line

March 12, 2014

Qatar: A Poet in a Desert Cell

November 1, 2013

The Last Colony?

October 15, 2013

Parallel Universe in a Glassed Concert Hall in Iceland (79th PEN Congress in Reykjavik, Iceland)

September 16, 2013

Living In and Beyond History (WiPC Conference in Krakow, Poland)

May 20, 2013

Two Voices Behind the Iron Doors

April 8, 2013

North Korean Writers in a Land of the Rising Sun (78th PEN Congress in Gyeongju, South Korea)

September 15, 2012

facebook or not?

June 28, 2012

Voices Around the World

January 30, 2012

Bridge Over the Bosporus: Citizenship on the Rise (77th PEN Congress, Belgrade, Serbia mentioned)

September 28, 2011

Tourist in Beijing: A Dance with the Censor

July 29, 2011

Ice Flows: Freedom of Expression

January 29, 2011

In the Woods: On History’s Doorstep

December 22, 2010

Full Moon Over Tokyo (76th PEN Congress in Tokyo, Japan)

September 30, 2010

Introducing Isabel Allende

May 21, 2010

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”–2

March 31, 2010

“Because Writers Speak Their Minds”

February 24, 2010

Haitian Farewell

January 18, 2010

Yellow Geranium in a Tin Can

October 27, 2009

China at 60–Fate of Liu Xiaobo?

September 30, 2009

A Time of Hopening (WiPC Conference in Oslo, Norway)

June 24, 2009

“There Will Still Be Light” *

April 30, 2009

The Intensifying Battle Over Internet Freedom

February 24, 2009

Charter 08: Decade of the Citizen

December 30, 2008

China from the 22nd Floor (Hong Kong Conference)

May 28, 2008

OLYMPIC RELAY– A POEM ON THE MOVE

April 21, 2008

Words That Matter

March 4, 2008

PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

January 2007 began with an assassination. The Board of PEN International was just gathering in Vienna for the first meeting of the year when board member Eugene Schoulgin got a phone call letting him know that our colleague and his friend Turkish-Armenian editor Hrant Dink, had been gunned down in Istanbul and killed. Many of us had seen Hrant at the PEN Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul in March.

Editor-in-chief of the bilingual Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, Dink had long advocated for reconciliation between Turks and Armenians and for Turkey’s recognition of the Armenian genocide early in the century. Dink had received death threats before and had himself been prosecuted for “denigrating Turkishness,” but as with Russian colleague Anna Politkovskaya, Dink’s assassination stunned us all and set off widespread protests in Turkey and abroad. Eventually a 17-year old Turkish nationalist was arrested and convicted, but not before police were exposed posing and smiling with the killer in front of a Turkish flag.

PEN International Board Meeting, Vienna, January 2007. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary; Jiří Gruša, International President; Caroline McCormick, Executive Director; Judy Buckrich, Women Writers Committee Chair; Elizabeth Norgdren, Finish PEN; Eugene Schoulgin, Norwegian PEN; Franca Tiberto, Search Committee Chair; Sibila Petlevski, Croatian PEN; Britta Pedersen, International Treasurer; Eric Lax, PEN USA West; Mohamed Magani, Algerian PEN; Kata Kulavkova, Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair; Frank Geary, Programs; Karen Efford, Programs.

The work of PEN is, at its heart, personal. It is writers speaking up for and trying to protect other writers so that ideas can have the freedom to flow in society. In league with other human rights organizations, PEN also advocates to change systems that allow attacks and abuse. At times the work can feel ephemeral when the systems don’t change, or make progress only to regress. However, the individual writer abides, and PEN’s connection to the writer stands.

During my tenure working with PEN, Turkey and China have been the two countries that have imprisoned the most writers. For a period both nations appeared to be advancing towards more open societies but soon retreated. In the early 2000’s as Turkey aspired to join the European Union, the country operated as a democracy with a more independent judiciary; fewer writers became entangled in the judicial processes. However, in 2007 the democratic transition in Turkey began to veer off course and has continued a downward spiral towards authoritarianism ever since.

China also promised to become a more open society with the advent of the Olympic Games in 2008. Democracy activists inside and outside of China grew hopeful. In this climate, PEN held an Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in Hong Kong in February 2007; it was PEN’s first in a Chinese-speaking area of the globe. Over 130 writers from 15 countries gathered, including writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and many of PEN’s nine Chinese-oriented centers as well as members from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Nepal, Australia, the Philippines, Europe, and North America.

Both China’s and Turkey’s Constitutions protected freedom of expression in theory, but in practice the protection was lacking. Instead, laws and regulations prohibited content. In Turkey, exceptions included criticism of Ataturk, expressions that threatened “unitary, secular, democratic and republican nature of the state” which in effect targeted issues around Kurds and Kurdish rights. In China, the Constitution noted that “in exercising their freedoms and rights, citizens may not infringe upon the interests of the State, of society or of the collective, or upon the lawful freedom and rights of other citizens.” The state was the arbiter.

The Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 took place at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories with programs also at Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club. The theme Writers in the Chinese World celebrated Chinese literature and a dialogue among PEN’s Asian centers and also explored issues of translation, women, exile, peace, censorship, internet publishing, freedom of expression and PEN’s strategic plan.

Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories. Over 130 writers from 20 PEN centers in 15 countries gathered for the four-day conference.

However, 20 of the 35 mainland Chinese writers who planned to attend were prevented or warned off by government authorities, including the President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) Liu Xiaobo, who later won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 while imprisoned in a Chinese jail. Qin Geng had his permit rescinded and two writers—Zan Aizong and Zhao Dagong—were stopped at the border and denied permission to exit though they had permits. (Two overseas Chinese writers who attended and had other citizenship—Gui Minhai and Yang Hengjun—are now in prison in China and are PEN main cases.)

In addition, the Chinese Communist government banned eight books, including one by Zhang Yihe, an honorary board member of the ICPC who had been invited to speak at the conference but instead was warned not to attend.

China’s promised opening of its society was already contracting, and the restrictions bore a harbinger of events to come both for writers and eventually for Hong Kong. The conference attracted wide press attention with articles in Chinese and English newspapers in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and globally via the BBC and newswire services. Renowned Shanghai playwright Sha Yexin, poet Yu Kwang-chung (Yu Guangzhong) from Taiwan and Korean poet Ko Un, short-listed for the Nobel Prize for Literature, attended. But the restrictions on the mainland Chinese writers cast an ominous shadow and grabbed the largest regional and international headlines.

“PEN has nine centers representing writers in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and abroad and has great respect for Chinese Writers and Chinese literature,” International PEN President Jiří Gruša told more than 40 reporters at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, “but we are very concerned by the restrictions on writers in mainland China to write, travel and associate freely.”

In honor of the absent writers, an empty chair sat on the platform for each session of the four-day conference.

Press Conference at Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, February 2007; L to R: Translator, Journalist Gao Yu (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Jiří Gruša (PEN International President), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary)

In 2007 more than 800 writers were under threat worldwide, and at least 33 writers were in prison in China. A number of the attendees at the conference had been imprisoned and been main cases for PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), including celebrated Korean poet Ko Un and Chinese journalist Gao Yu, both of whom addressed the conference. They knew firsthand the role of the writer in the struggle for freedom, and they knew the support PEN had given, observed one of the conference organizers Yu Zhang, General Secretary of the ICPC, half of whose members lived in mainland China.

“I am no longer afraid of anything,” one Chinese writer unable to attend said in a message to the conference. “Our bodies and our spirits are our own. To speak of ugliness and injustice we have to shout, but our throats are cut when we do.”

“We are willing for some things to be burned in the soil so a new leaf will come,” added another mainland writer in a message to the conference.

“It is important that all writers get together, and all writers protect the freedom of speech and free expression. We must write what’s in our hearts and write as a witness to history,” said Qi Jiazhen, who spent 10 years in a Chinese prison and now lived in exile.

Owen H.H. Wong of Hong Kong’s English-Speaking PEN Center pointed out that Hong Kong was a meeting point of East and West, North and South, Leftists and Rightists and Modernization and Classic writing. He noted that before the 1997 handover, Hong Kong writers saw themselves as writers in exile. Only those born in Hong Kong regarded themselves as Hong Kong writers. Now most publishing houses in Hong Kong were funded by the Communist government, and free expression in Hong Kong was threatened and controlled.

Yu Jie, a Beijing-based essayist and author and vice President of ICPC, spoke at the Foreign Correspondents Club noting that even though he was able to attend the conference and speak to the foreign media, he had not been able to get published in mainland China. For mainland writers, Hong Kong was a place where freedom of expression and freedom of the press still existed, he said. “It’s as if those of us in the mainland have our heads immersed in water and cannot breathe, but Hong Kong allows us to stick our heads above the surface of the water, and for a short time, breathe freely.”

He predicted that the authorities would later “settle the score” with the writers and publishing houses. He was in fact later arrested, tortured and imprisoned for his writing. In 2012 he emigrated to the United States.

PEN International Panel at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference. L to R: Conference organizers included Yu Zhang, (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director), Chip Rolley (Sydney PEN)

“Existing in the unofficial nooks and crannies of an emerging civil society in China, ICPC is determined to insist that their country live up to the rights guaranteed in its Constitution,” said another conference organizer, Chip Rolley, Vice President of Sydney PEN. “This continuing work will ensure that there is indeed a turning point for PEN in China and the wider Asia and Pacific region, and that this historic conference will not dissipate like smoke.”

In his keynote address Taiwanese writer and poet Yu Kwang-chung called for “all the writers and the poets across the Chinese world” to strengthen the channels of mutual exchange, and make efforts to find a consensus on basic issues such as the formation of a common national culture (which includes in particular the establishment of joint aesthetic and literary values) in order to “make a valuable contribution to preventing war and maintaining peace.”

Attendees launched a dialogue on literature as well as on networking among PEN’s Asian centers with a regional strategy for freedom of expression and translation. The conference was part of PEN International’s program to develop the regions in which PEN operated by connecting existing writers and PEN centers and also developing new centers in countries starting to open up such as Myanmar/Burma. Often a PEN center was one of the first civil-society organization to set down roots when authoritarian controls began to relax. [A Myanmar PEN Center was established in 2013.]

In a panel on Literature and Social Responsibility panelists noted that free speech and writers’ responsibilities were the basis of social prosperity and that PEN was a bridge between writers and their responsibilities.

Participants at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, Nepal, including speaker Yu Kwang-chung (Taiwan) seated in center.

Chen Maiping of ICPC read a message from Zhang Yihe, the mainland novelist who was to have been on the panel but who had been prevented from attending. “There is a saying: human hearts are like water, while people’s favor and loyalty feel as heavy as mountains. During these ten plus days since my books were banned, so many people have shown their concern I have nothing to give in return for their kind support other than to express my gratitude on paper. Writing is my only means of self-expression. Writers have always been prisoners of language and words. It is not an easy affair for me to live, nor can I die in peace. I can only write…In China we talk about ‘literature as a vehicle for the Tao (the Nature, the Way).’ People have talked about this for thousands of years. However, those who have written the best literature are exactly those who never think about their social responsibility. Zhang Bojun [the author’s father who was a scholar and a minister in the Chinese government in the 1950s and persecuted during the 1957 Anti-Rightist campaign in Mao’s Cultural Revolution] was an example of this. In my view his achievements were much greater than many of the contemporary writers, artists and painters. If a writer has too strong a responsibility, he may have no achievements at all.

“For several decades, literature has been tied together with ‘revolution’ and ‘reform.’ I can’t bear such responsibility. I can only recall the past. I do not have such social responsibility tied to ‘revolution‘ and ‘reform.’ I am out of date. There are so many people singing praise for the society, why not allow an old woman like me to sing a little song of my own. I am only a piece of withered leaf. I hope that I can decay quickly so that I may become a new leaf soon. “

Chen Maiping also read “Writing in Anger” by Liu Shu, another mainland writer prevented from attending. “The conflicts between our hearts and reality and an unwillingness to keep silent are the driving forces for my writing. The disgraceful politics have turned us into dissident writers. Chinese dissident writers write in isolation. The marginalized position of dissident writers has marginalized their writing. This is very different from the West. The Eastern people have the ability to suffer and digest their sufferings. This kind of ability enables writers to ignore the reality and to become numb to the suffering of their people. They choose to write only about ‘pleasant things to lighten the load on their hearts.’

“The cruelty of reality fills their lives with ‘submission.’ The writers are swollen and weighed down with humiliations and sufferings; they have lost the anger created by their reality. They have no anger at the past, nor do they imagine a future. They only write about meaningless, shallow and trivial affairs. My anger comes from my refusal to accept and make peace with this reality. I have been detained four times because of my ideas. We puzzle over social phenomena but we long for peace. The way to calm our anger is to write…I must speak for citizens who were screened by the totalitarian society, by the police and the ugly society…we do not want to be silent. Like Lu Xun said, life is ourselves: everybody is responsible for his own life. Our flesh body and our life are in exile in our homeland, until we disappear.”

Women Writers Committee gathering at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference including Chair Judy Buckrich in turquoise in center.

Women participants at the conference focused in addition on the restrictions for women writers in the region.

Qi Jiazhen was imprisoned 10 years and accused of trying to overthrow the government after she inquired whether she could study aboard. She said she had been young and inexperienced and felt guilty and wrong, the same feeling shared by other women. Gender awareness was low in China, she said. She now lives in Melbourne, Australia.

Celebrated mainland journalist Gao Yu confirmed two kinds of prisoners in China—special treatment prisoners & prisoners of conscience. As vice chief editor of an economic weekly with an international reputation, she was a special treatment prisoner. She had treatment when she was sick and had to do little hard manual work because was already 50 and given 7 years in prison. But she never admitted her wrong doing so she didn’t enjoy any pain reductions, she said.

Chinese journalist and PEN main case Gao Yu with translator.

In a panel on Censorship and Self-Censorship, Gao Yu noted that censorship began at school where children learned to protest injustice when not treated fairly. Later in life that grew into resistance of the system. The writer who sought to express truth experienced censorship which could lead to punishment and prison. But that was not as frightening as being silent, she said. The essence of being a writer was to have integrity and speak the truth.

After the conference, a dozen police picked up one participant and took him to a hotel room to find out what the conference had been about. A poet and member of ICPC, he told the police, “To build a ‘harmonious society’ and ‘harmonious culture’ [as President Hu Jintao has called for], writers should sit with writers and not always have to sit with policemen.” He was finally released after hours of interrogation.

One of the more creative campaign tools planned during the conference was spearheaded by a team of PEN Centers in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. The members developed a digital relay with Chinese poet Shi Tao’s poem June. The poem tracked the path of the Olympic torch across a digital map. Shi Tao was serving a 10-year prison sentence for sharing with pro-democracy websites a government directive for Chinese media to downplay the 15th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests. His emails had been turned over to the Chinese government as evidence by Yahoo. His poem commemorated the Tiananmen Square massacre and was translated and read in the languages of PEN’s centers around the world, including in regional dialects as well as in the major languages. Ultimately 110 of PEN’s 145 centers participated and translated the poem into 100 languages, including Swahili, Igbo, Krio, Tsotsil, Mayan. The poem’s journey began on March 30, 2008 in Athens and traveled to every region on the online map, arriving in Hong Kong on May 2 and in June to Tibet where it was translated into Tibetan and the proposed Uyghur PEN center translated it into Uyghur. Finally August 6-8 it arrived in Beijing where it was translated and read in Mandarin. Anyone could click on the map and hear the poem in the language of the country designated.

By the 2008 Olympic Games 39 writers remained in prison in China.

June

By Shi Tao

My whole life

Will never get past ‘June’

June, when my heart died

When my poetry died

When my lover

Died in romance’s pool of blood

June, the scorching sun burns open my skin

Revealing the true nature of my wound

June, the fish swims out of the blood-red sea

Toward another place to hibernate

June, the earth shifts, the rivers fall silent

Piled up letters unable to be delivered dead.

(Translated by Chip Rolley)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 44: World Journey Beginning at Home

PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I first visited Berlin in the fall of 1990 just after Germany reunited. I was living in London and took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to witness history in the making. I returned on a number of occasions, researching scenes for a book, attending meetings, and visiting German PEN in preparation for PEN’s 2006 Congress. Each time Berlin’s face was altered as the municipalities east and west moved to become one city again.

PEN International’s 72nd World Congress, Berlin, 2006

At the time of PEN’s Congress in May 2006, Berlin was bedecked with water pipes above ground—pink, green, blue, red—before the city buried its plumbing and infrastructure beneath the streets. Portions of the city had the appearance of an amusement park; there were also sections of the Berlin Wall with its colorful graffiti still standing, more as art exhibit than stark barrier to freedom.

“Welcome to a United Berlin” the German PEN President headlined his letter to the 450 delegates and participants for PEN’s 72nd World Congress. The Congress theme “Writing in a World Without Peace” was challenged by the reunification of Berlin and Germany, a historic event which bode well for the prospects of peace and which stood in contrast to the history that had come before. Yet the globe was still in conflict in the Middle East, in Asia and in Latin America where writers were under threat.

“There are countries such as Iran, Turkey or Cuba, where authors are jailed because of their books,” noted International PEN President Jiří Gruša. Resolutions at the Congress addressed the situations for writers imprisoned or killed in China, Cuba, Iran, Mexico, Russia/Chechnya, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and other countries.

Left: Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) meeting at Berlin Congress. Karin Clark (Chair WiPC) and Sara Whyatt (WiPC Program Director). Right: WiPC Conference in Istanbul: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN/PEN Board), Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Jonathan Heawood (English PEN), Notetaker

Two months before in March, over 60 writers from 27 PEN centers in 23 countries had gathered for International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul where the WiPC planned a campaign against insult and criminal defamation laws under which writers and journalists were imprisoned worldwide. The conference also addressed the recent uproar over the Danish cartoons, impunity and the role of internet service providers offering information on writers, especially in China. A working group formed to support the Russian PEN Center which was under pressure from the Russian government.

Berlin, however, was sparkling and filled with the energy of reunification. “Today, this city—once separated by a Wall most drastically manifesting the division of Germany and Europe—has not only been re-established as the capital of Germany, but has simultaneously turned into a thriving meeting-place between East and West and North and South,” welcomed Johano Strasser, German PEN President. “Here in Berlin, history in all its facets—from the great achievements of German artists, philosophers and scientists to the crimes of the Nazis—has left its mark on the urban landscape.”

Left: German Chancellor Angela Merkel addressing PEN members at 72nd PEN Congress, 2006; Right: PEN International President Jiří Gruša speaking to PEN delegates and members at the Federal Chancellery; front row: German PEN President Johano Strasser, Chancellor Angela Merkel and PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman. [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

The keynote address by Nobel laureate Günter Grass challenged the conflicts around the globe and the countries engaged in them. “There has always been war. And even peace agreements, intentionally or unintentionally, contained the germs of future wars, whether the treaty was concluded in Münster in Westphalia, or in Versailles,” he said.

Nobel laureate Günter Grass addressing Opening Ceremony of PEN International’s 72nd World Congress in Berlin, 2006 [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As I sat on the dais on the edge of the stage listening to this renowned German writer, I leaned over to Jiří and said, If there is a standing ovation, I can’t stand. I was concerned. Grass could say and think whatever he wanted, but PEN was a non-political organization. Whatever my views of my country’s foreign policy, I was an American; I was also the mother of a son in uniform. Jiří leaned back to me and said in effect: Don’t worry, I won’t stand either. The speech ended with applause but no ovation, and then everyone got up and went to the next event.

It wasn’t my role to argue with Günter Grass even had the occasion allowed. But it was important that PEN assure the open space for debate existed which it did later in the Congress workshops and programs. PEN was filled with a multitude of points of view among its members; it did not have a litmus test of politics, only a commitment to the free expression of ideas. It offered a wide tent where views could be debated and challenged. Dogmatic political certainties often fell on their own in the alchemy of literature and imagination.

PEN members and delegates from around the world at Opening Ceremony of 2006 PEN Congress [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

Programs at the Congress also featured Nobel laureate and PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer and writers from around the world, including former International PEN Presidents Ronald Harwood, and György Konrád, Bei Dao, A.L. Kennedy, Margriet de Moor, Péter Nádas, Per Olov Enquist, Mahmoud Darwish, Duo Duo, Jean Rouaud, Johano Strasser, Veronique Tadio, Patrice Nganang and others. These writers participated in the literary events, including an evening of African literature and one of writers of German literature who had immigrated from abroad to Germany or had non-German cultural backgrounds. Afternoon literary sessions included prominent PEN writers introducing authors of their choice, an afternoon of essays and discussions on the theme Writing in a World without Peace and a lyric poetry afternoon.

PEN’s 85th anniversary coincided with the 60th anniversary of the United Nations. Both organizations had been founded after a World War out of an idealism that arose from desperate times with the hope that the future could be better than what had just transpired. “Both organizations were founded on a belief in dialogue and an exchange of ideas across national borders,” I noted in my address to the Assembly of Delegates. “When U.N. members were writing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the framers consulted, among other documents, PEN’s Charter.”

PEN also had a history with the city of Berlin, where PEN members had gathered in 1926 for the first international meeting of importance held in Berlin after World War I. At that Berlin Congress tensions had arisen among old and young writers, writers from the west and the east, and debate had flared about the political versus the nonpolitical nature of PEN. The debate that stirred in Berlin in part led to the framing of PEN’s Charter the following year.

Since those early days, PEN had grown in size beyond what the founding writers might ever have imagined. After the 2006 Berlin Congress, with the addition of centers in Jamaica, Uruguay, and Pretoria, South Africa, PEN had 144 centers in 101 countries in almost every time zone. The PEN world didn’t sleep. Someone, somewhere was always awake doing something. Through its centers PEN International participated in at least a dozen conferences around the world each year, including meetings of its standing committees. PEN thought globally but worked locally.

Berlin—with its own alterations and progress—proved a fitting location for the presentation of International PEN’s new Three-Year Plan. For the past decade, since the 75th Anniversary at the Congress in Guadalajara, PEN International had been in an organizational reformation. It now had a governing structure with a global Board that participated in decision-making; it had revised its Constitution and Rules and Regulations; it had developed a budget, increased its funding, and recently moved its offices into Central London to a larger space with cheaper pro rata rent and an elevator, which had meaning for anyone who had climbed the steep four (or five?) flights to PEN’s old offices. The staff size had also increased, and PEN had hired its first Executive Director, Caroline McCormick Whitaker, former Development Director from the British National History Museum.

International PEN Board meeting preceding 72nd PEN Congress in Berlin, May 2006. L to R: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Kata Kulakova (Chair Translation & Linguistic Rights Committee), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Chip Rolley (Chair Search Committee), Karen Efford (Program Officer), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International PEN President), Peter Firkin (standing—Centers Coordinator), Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Jane Spender (Programs Director), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair)

Because British charitable tax law had changed, the opportunity had also arisen to unite International PEN and the International PEN Foundation into one charitable organization: International PEN, Ltd, a step that would provide the legal framework and protection for the organization and PEN’s name, would limit personal financial liability of the Board and attract a wider funding base. At the Berlin Congress, resolutions and approval were endorsed for this step which would be finalized the following year at the 2007 Congress in Dakar.

Caroline Whitaker took the Assembly of Delegates through the Three-Year Plan which had been developed after widespread consultation with PEN centers and the Board. She acknowledged that PEN couldn’t do everything that everyone wanted right away, that it was necessary to focus resources even as PEN developed more resources.

The Plan, which had grown out of all the discussions and preceding plans, concentrated on PEN’s three missions: to promote literature, to protect freedom of expression and to build a community of writers. “International PEN will work regionally to connect the activity of its many Centers around the globe on these issues,” Caroline told the delegates.

All PEN’s Standing Committees met at Berlin Congress—Writers in Prison Committee, Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women Writers Committee and Peace Committee [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

In helping to develop PEN’s centers, the Three-Year Plan recommended International PEN focus on one region at a time, beginning with Africa where the 2007 PEN Congress would be held. International PEN would assist in programming and fundraising for development of PEN’s African Centers. The next regional focus would be Latin America, where PEN’s 2008 Congress was to be held. This rolling focus would allow the limited international staff to plan strategically. Regular daily work would still continue for the needs of centers in all regions.

PEN members met in workshops at 72nd Berlin Congress. Topics: PEN in the World—Global Issues; Education; the Strategic Plan; Centers; Networks and Partners; Asia and Central Asia; Middle East; Africa; Europe and Americas [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As International PEN’s work had taken me across the globe that year, I’d come to see that PEN and its members formed a kind of intricate net which helped hold civil society together, the kind of sturdy net used on hills to prevent landslides. In a way that is what PEN members did around the world. They helped prevent literary culture and languages and freedom of expression from slipping away by both their active programming and their defensive actions

At the 1926 PEN Congress in Berlin International PEN’s President John Galsworthy and PEN’s founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott had their voices recorded and preserved in a project of the German state. Galsworthy read a page from his Forsyte Saga. According to Dawson Scott’s journal, she recorded the following: “Even as individuals become families and families become communities and communities become nations, so eventually must the nations draw together in peace.”

It was a worthy, if not yet realized goal, but at least in PEN we had a global family.

Mayor’s reception for PEN members and participants at 72nd World Congress in Berlin, May 2006 [Photo Credit: Tran Vu]

Elections at 2006 Congress:

International PEN President: Jiří Gruša was re-elected for further 3-year term.

International PEN Board: Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian Center) and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN re-elected to the Board)

Vice Presidents: Toni Morrison (American PEN) and J.M. Coetzee (Sydney PEN) elected Vice Presidents for service to literature and Gloria Guardia (Panamanian Center) for service to PEN

Women Writers Committee: Judith Buckrich (Melbourne Center) re-elected as Chair

Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee: Carles Torner (Catalan PEN) stood down as Vice Chair, replaced by Josep Maria Terricabras (Catalan PEN)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 42: From Copenhagen to Dakar to Guadalajara and in Between

PEN Journey 40: The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At the end of September 2005 a Danish newspaper published 12 editorial cartoons which depicted Mohammed in various poses as part of a debate over criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark objected, and by early 2006 protests, violent demonstrations and even riots erupted in Muslim areas around the world. The offense was the “blasphemy” of drawing Mohammed in the first place and the particular mockery of some of the depictions in the cartoons.

The uproar over the Jyllands-Posten Mohammed cartoons quickly drew PEN into the controversy, first through Danish PEN and then through the International PEN office and other PEN Centers. PEN included many Muslim members and numbers of centers in majority Muslim countries. All PEN members and centers endorse the ideals stated in the PEN Charter. However, the third and fourth articles of the Charter which addressed the situation, also at times appeared to contradict each other:

Article 3: “Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel all hatreds and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

Article 4: “PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world toward a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restrain, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

PEN International Board and Staff 2006. L to R: Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Elizabeth Nordgren (Finish PEN), Jane Spender (Programs Director) Sara Whyatt (Writers in Prison Committee Director), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Karen Efford (Programs Officer), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International President), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Britta Junge-Pederson (Treasurer), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair), Chip Rolley (Search Committee Chair), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Peter Firkin (Centers Coordinator) [not pictured: Mohammed Magani (Algerian PEN), Karin Clark (WiPC Chair), Kata Kulavkova ( Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair)

Peace Committee program 2006. Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Veno Taufer (Peace Committee Chair)

At the Peace Committee conference that April, I observed, “The Charter of PEN asserts values that can appear contradictory, but represent the dialectic upon which free societies operate and tolerate competing ideas…In our 85th year, International PEN still represents that longing for a world in which people communicate and respect differences, share culture and literature, and battle ideas but not each other.”

The Danish cartoon controversy led off 2006. For me, the PEN year also included attending the conferences of three of PEN’s four standing committees—the Peace Committee in Bled, Slovenia, Writers in Prison Committee in Istanbul, Turkey (PEN Journey 35) and Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee in Ohrid, Macedonia (PEN Journey 39)—and in May the 72nd PEN World Congress in Berlin, and later a Danish Conference on the Middle East in Copenhagen, the Gothenburg Book Fair in Sweden, a PAN Africa Conference in Dakar, Senegal and a trip to Moscow, where I went to watch my oldest son compete in the European Wrestling Championships and visited Russian PEN on a mission.

Russian PEN members meeting in Russian PEN office, including Alexander Tkachenko, General Secretary, 2006

To Moscow I took just under $10,000 raised by PEN centers and buried in my luggage to help the Russian PEN Center. Vladimir Putin and the Russian government had begun to crackdown on nongovernmental organizations with ties to other countries. One of their first targets was Russian PEN which had opposed the legislation restricting nongovernmental organizations. At the time I was also on the board of Human Rights Watch, a larger organization which was watching closely what was happening to PEN. The government’s attack on Russian PEN came in the form of a freeze on all assets for failure to pay a land tax. Russian PEN argued that it was a legal tenant where it had been conducting business and was not liable for the tax on the land, but the tax office refused to drop the charges. The government threatened to close PEN and take away its office if the money wasn’t paid. An appeal had gone out to PEN’s other centers, which had responded from around the globe not only with protests to Moscow but also with funds for Russian PEN.

I brought in funds just under the amount I would have had to declare. During the wrestling tournament I met with Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko, the General Secretary of Russian PEN, and delivered to him the donation, and he gave me a receipt. The funds stayed off the crisis for then. Charges were dropped. A Russian Minister said, “I don’t understand. I was getting letters from as far away as Argentina!” Sascha answered him: “That is the kind of organization we are.” PEN continued to operate.

In Moscow I also met with Russian PEN members as well as with Turkmen author Rakhim Esenov, who was visiting Russian PEN. I had met Esenov a few weeks before in New York where he had won PEN America’s Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write award. In Turkmenistan Esenov had been charged with “inciting social, national and religious hatred using the mass media” because of characters in his novel The Crowned Wanderer. Set in the 16th century Mogul Empire, the story focused on a poet/philosopher/army general who was said to have saved Turkmenistan from fragmentation. The president of Turkmenistan Saparmurad Niyazov banned the book for portraying the main character as a Shia rather than a Sunni Muslim, and he imprisoned Esenov for several months. I still have the massive Russian language volume he shared with me, a work that had taken him years to write.

L to R: Russian PEN General Secretary Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko and Russian PEN member outside Russian PEN office in Moscow and Rakhim Esenov, author of The Crowned Wander and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), 2006

At the Peace Committee conference earlier that month I’d presented a paper on the conference theme “The Role of PEN in the Contemporary World,” a broad and challenging topic which had inspired me to peer both backward and forward.

Below is the beginning of that paper with a link to the rest:

My first memory of a PEN meeting was sitting in someone’s living room in Los Angles writing postcards to free Wei Jingsheng from prison in China. At the time in the 1980’s he’d already been in prison several years of a fifteen-year sentence. I had no idea who this writer was thousands of miles away. I barely knew the other writers in that living room. On the coffee table would have been PEN’s Case List, which at the time was white sheets of paper stapled together.

We wrote and stamped our post cards for Wei and other writers that afternoon. I’m sure we were provided with background on his case. I pictured these cards fluttering into a jail somewhere in China and perhaps even into the cell of this stranger to let him know we had taken note of him and cared what happened. Looking back on the blue-sky afternoon as we sipped sodas and ate crackers and cheese, I see our act as a bit fleeting, an effort to imagine the fate of another writer who didn’t have our freedom to write and speak…[continue reading here]

Next Installment: PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN Journey 37: Bled: The Tower of Babel—Part Two

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

At PEN’s 71st World Congress in June 2005 over 275 writers from 88 PEN Centers gathered from around the world in the idyllic setting of Bled, Slovenia where history had been made 40 years before. In 1965, PEN had held its Congress in Bled, the first in Eastern Europe since the Second World War. Russian writers visited PEN for the first time. At that 33rd World Congress, American playwright Arthur Miller, who’d recently passed away in 2005, had been elected the first and only American President of International PEN.

Lake Bled in Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International’s 71st World Congress, 2005

In 2005 the global dynamics had changed. PEN now had active centers in most of the countries in the former Communist Eastern bloc, including in Russia. The European Union (EU) was in its ascendancy; 2005 marked Slovenia’s accession into the EU. Globalization was bringing benefits but also threats to the cultures of smaller countries.

Reception 71st PEN Congress in Bled, 2005. L to R: Frank Asare Donkoh (Ghana PEN), Jane Spender (Program Director PEN International), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (PEN International Secretary), Alfred Msadala (Malawi PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (PEN Executive Director), Dan Khayana (Uganda PEN), Bao Viet Nguyen-Hoang (Suisse Romand PEN) [Photo credit for many photos: Tran Vu]

“We live in an age when many preconceived ideas, nurtured for centuries and ostensibly immutable, are no longer valid,” noted Slovene PEN President Tone Peršak. “The linguistic and cultural image of the world is in flux and civilization as a whole, under the influence of globalization, is taking on a new character. These events are also echoed in discussions within PEN centers…They guided us in our selection of the main topic for discussion at the Congress, namely the issue of linguistic and consequently cultural diversity of the world. The topic is proposed as a question: does linguistic diversity stimulate or hinder cultural development? Is it a curse or a blessing that made possible the emergence and encounter of various world views, different emotional responses to the human destiny, and finally also brought about the formulation of different schools of thought and philosophical doctrines?

“We regard the question of linguistic and cultural diversity also as a human rights issue. Attempts to unify and subject all aspects of life to uniform standards and norms is viewed as a very questionable encroachment on these rights. One of the topics is therefore the question of the need to protect languages and cultures, and that means also the smallest ones which may be on the verge of extinction. Let us also draw your attention to literature’s role in the preservation of the memory of the cultural landscape, which has been undergoing considerable changes and in some cases may even disappear forever…[Is] literature a kind of lingua franca which could and should contribute to a better mutual understanding and insight into the different cultures and nations that sustain cultural diversity?”

These were questions without definitive answers, but questions that occupied writers from dozens of cultures and languages in the Congress’s literary sessions. [At PEN Congresses, the main sessions and the Assembly of Delegates were usually translated into PEN’s three official languages—English, French and Spanish—and also the language of the Congress host.]

PEN International Congress Bled, Slovenia 2005. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Monika Van Paemel (Belgium (Dutch-speaking) PEN), Alexander Blokh (French PEN and former PEN International Secretary), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Jiří Gruša (President, International PEN)

A number of the delegates had before been to Bled, home of PEN International’s annual Writers for Peace Committee conference, hosted by Slovene PEN. During the Cold War the Peace Committee, founded in 1984, provided one of the only open forums for dialogue between writers from the East and West.

“Let us learn the language of our neighbors so that we all may better come to know and understand our neighbors and forestall incomprehension and conflict,” the Peace Committee and the Congress organizers urged.

In my own address to the Congress as International Secretary, I relied on the prevailing metaphor of the bridge, using an example close to home:

I recently crossed a soaring new bridge in Boston, Massachusetts, a bridge at least 14-years in the making. This bridge spanning the Charles River was the result of what is called the Big Dig, a project anyone who has lived in or regularly visited Boston has come to think of as the Eternal Dig for it is hard to remember when a large segment of downtown wasn’t under construction. But at last there is this soaring bridge with stanchions into the sky in gracious arcs and at night a blue light shining up into its cables as it rises above the city. There is also an elaborate network of freeways and tunnels underground.

I sometimes think International PEN is a bit like the Big Dig. For much of the last decade we’ve been reconstructing ourselves, trying to reflect in our governing structures the expansion that PEN has experienced across the globe, an expansion brought on in part by the opening up of societies after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the lifting of the so-called Iron Curtain. This expansion has also been enabled by the linking of the globe through the internet. International PEN has instituted a Board, been through a long range planning process, revised rules and regulations, and while we still have construction going on and probably always will, I’m hopeful that we too will start to see more and more of the benefits of all this work…Throughout we’ve continued to witness remarkable activities from our Centers…

This year I’ve been telling people that PEN is a place where cultures don’t clash but communicate. PEN members may not always agree, in fact frequently don’t agree, but the fellowship among members can keep that disagreement from turning into confrontation. At our best PEN’s forums offer a place where the energy of competing ideas releases light, rather like that spectacular blue light which shoots upwards on the cables of the grand bridge in Boston.

Arthur Miller once described PEN: “With all its flounderings and failings and mistaken acts, it is still, I think, a fellowship moved by the hope that one day the work it tries and often manages to do will no longer be necessary. Needless to add, we shall need extraordinarily long lives to see that noble day. Meanwhile we have PEN, this fellowship bequeathed on us by several generations of writers for whom their own success and fame were simply not enough.”

The work included substance and form, the latter focusing on the organizational structure which allowed the work to go forward. At the Bled Congress the delegates approved procedural reforms, broke into workshops to discuss PEN itself and global and regional issues, and were introduced to PEN’s first Executive Director, who would begin the following month. After an extensive search, the board and staff had agreed to hire Caroline Whitaker (née McCormick) who had worked in theater development, had a degree in literature and was coming to PEN from the Natural History Museum where she was Director of Development.

Writers in Prison Committee and Workshop Sessions, PEN International Congress, Bled, Slovenia, June 2005

At the Congress seven candidates from Algeria, Colombia, Croatia, France, Finland, Japan, and Russia ran for positions on the International Board, and Mohamed Magani (Algerian PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), and Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN) were elected.

The Congress discussed and passed over 20 resolutions and actions challenging the situations for writers in Algeria, Basque region of Spain, Belarus, Burma, China, Cuba, Iran, Maldives, Mexico, Nepal, Russia, Syria, Tibet, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam as well as resolutions relating to the attacks on journalists in war zones and the crackdown on internet writing in Tunisia where the World Summit on the Information Society was to be held that fall.

The Congress also noted the tenth anniversary of the death of PEN member Nigerian writer Ken Saro-Wiwa. International PEN President Jiří Gruša noted: “We are living in a time of extraordinary threats to writers and the freedom to write. In the ten years since our colleague Ken Saro-Wiwa was executed in Nigeria, hundreds of writers and journalists around the world have died by violence. Crackdowns on internet writers and anti-terrorism legislation have named writers and chilled freedom of expression in a number of countries.

“While our colleagues in countries such as Myanmar, Cuba, China and Belarus continue to struggle against conventional governmental censorship and repression, writers also face the threat of moral violence in countries from Mexico to Iraq and new pressures associated with writing and publishing on the internet.”

Among the guests at the Congress were Colin Channer, who introduced the prospective Jamaica PEN Center which was voted into PEN at the subsequent 2006 Congress in Berlin.

And for the first time since the Tiananmen Square massacre June 4, 1989, a writer from the People’s Republic of China attended as a representative of the new Independent Chinese PEN Center whose members included writers from inside and outside of mainland China. I include below much of his talk which rings truer than ever.

Wang Yi* addressed the Assembly, noting that this was the first time in 16 years “the voice of a non-official and independent Chinese writers’ group could be heard, a group that is independent or at least strives for its independence, that is free or at least longs for freedom and that tries to perpetuate the freedom of expression in the face of great political pressure…

Wang Yi (Independent Chinese PEN Center)

“I come here heavy-hearted without blessing, because there is no reconciliation between a free writer, an independent intellectual, and his government. I come to Bled representing those who have been disgraced, who have stood in the shadow of terror and the peril of political oppression, and who have yet never resigned but have insisted upon their freedom of speech and writing, such as Mr. Liu Xiaobo whose work has been not allowed to be published and who has not been allowed to go abroad. I also come for myself, who experienced in the sixteen years after Tiananmen a long period during which memories have been erased forcefully and silence has been ordered. This has been a time during which mothers, who lost their sons and daughters at Tiananmen, have not been allowed to weep…

“To me and my colleagues, writing is a rescue plan for the hostage. Writing means dignity and freedom; it is kind of belief. But we cannot rescue ourselves, even when we have courage and when justice is on our side in the face of institutional arbitrariness…

“Our salvation depends upon that higher community, depends upon common universal values that we share as writers, as free people and as intellectuals. It is the source of liberty and imagination…

“We are disappointed to see that some European governments are gradually abandoning free values and lessening their criticism of the despotic regime in Beijing. For a common benefit they abandon the writers, reporters, dissidents and orators who are imprisoned…

“According to the Independent Chinese PEN club, more than 50 writers and reporters are currently in jail…

“I want to mention two points: the first one is the belief that through writing, we can enlighten and preserve basic human values. Second, there is a global realistic linguistic environment. These two points make me think that the persecution of Chinese, Tibetan, Uighur and other minority writers reaches across borders to become an international issue…There is only the suppression of the right to freedom of expression and the persecution of human beings, which needs to be rooted out, and the victim needs to be consoled and supported…

“The Chinese government’s suppression of writers has accelerated in recent years, since the beginning of the Internet era…pen names and pseudonyms are prohibited. With this act, the last bastion of self-protection is destroyed.

“Every morning, the Communist Party’s propaganda department issues a list of prohibited news to the media. Whoever dares to break the taboos will get into big trouble. As the government stifles the mouths of the media and betrays the public, it also tampers with the truth in historical textbooks and deceives the children in school. An increasing number of courageous writers, reporters and public figures are daring to challenge the status quo so more and more of them have been thrown into jail on charges of committing the crime of “instigation and subversion of the state” or “disclosing state secrets” to “hostile forces…

Liu Xiaobo and Yu Jie (Independent Chinese PEN Center)

“Among the harassed and persecuted are also the president of ICPC and his deputy, Mr. Liu Xiaobo* and Mr. Yu Jie*. Under such circumstances, you cannot but regard the Chinese writer as a hostage…

“I come to Bled hoping to present myself as a writer, but I am indeed only a hostage…One of the reasons that I definitely wanted to come is that I believe we all belong to the same world. In this world, the state, the glory and the lawful right all belong to that higher spiritual origin that makes us, without regret, proud to be a writer.”

*[Wang Yi, deputy Secretary General of ICPC 2003-2007, has been imprisoned in China since December 2018, serving a 9-year sentence for “activities disobedient to the government control” and “inciting subversion of state power and illegal business.” Wang Yi is a writer and a Christian pastor. Liu Xiaobo, the second President of ICPC, was sentenced in December 2008 to an 11-year prison sentence as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power.” He was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 and died in custody June 13, 2017. Yu Jie, a celebrated writer, was one of the drafters, along with Liu Xiaobo, of Charter 08, which set out a democratic vision for China; he was arrested and tortured in 2010 and immigrated to the U.S. in 2012. He is author of Steel Gate to Freedom: The Life of Liu Xiaobo.]

Lake Bled, Slovenia, site of PEN International 71st World Congress, 2005

Next Installment: PEN Journey 38: PEN’s Work On the Road in Kyrgyzstan and Ghana