PEN Journey 22: Warsaw—Farewell to the 20th Century

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

Bombs had been falling for months on Serbia when the 66th PEN Congress convened in Warsaw June 1999. The NATO assault—one of the last major campaigns of the Balkans War—ended just a week before the Congress opened. These events stirred debate at the Congress whose theme Farewell to the 20th Century caused delegates to look back as well as forward in deliberations.

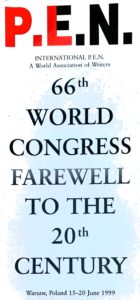

The past included Warsaw’s history as well as its proximity (and a post-Congress trip) to Kraków and to the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau. I didn’t join the PEN trip, but during the Congress, I went on my own one day to these memorials of World War II’s terrible past so that I could walk and think alone among the empty crowded bunks, the piles of shoes, the ovens…

The Warsaw Congress was my first trip to Poland though not my last and my first visit to a concentration camp, though not my last.

Program for PEN International Congress, Warsaw, Poland, 1999

The wars of the 20th Century both past and current were a problematic platform upon which to launch into the new Millennium, yet the century also was a time of citizens coming together and speaking out in such organizations as PEN. One of the panels at the Congress included the topic: the Role of International Writers’ Organizations in the 20th Century and their Association with UNESCO. An arcane topic perhaps, but one that begged a longer look at the future of the global organization of civil society.

PEN International President Homero Aridjis addressed the Assembly of Delegates from over 70 PEN centres, noting, “Ever since the day twelve weeks ago when the NATO bombing of Serbia began and a tidal wave of refugees from Kosovo overwhelmed neighboring countries, I have been thinking about what writers can do when war breaks out, and when ethnic rivalries and deep-rooted hatreds flare up, and about whether and how what we do can help prevent conflicts from reaching the point of explosion, when people are forced to abandon their homes and flee across borders. PEN is experienced in assisting writers who suffer in these situations, whether they are victims of censorship or their personal safety is threatened. But what is the nature of our commitment to the peaceful resolution of conflict? Or is the use of force legitimate to achieve aims which may seem unattainable otherwise?

“Writers around the world, but especially in the United States and Europe, reacted vehemently to the situation in the Balkans and often clashed,” he said. “Accusations flew back and forth across the Atlantic and were widely aired in the written and broadcast media. I myself was repeatedly asked to give PEN’s position on the conflict, and found myself bound by the principles expressed in PEN’s Charter, and by our commitments to protect and defend individual writers who are threatened and to uphold freedom of expression wherever it is under siege. An important part of our response is, of course, through the PEN Emergency Fund, where the thorough research always done by PEN ensures that assistance goes to truly deserving individuals. A new PEN endeavor may also soon be taking shape in the form of a writers in exile network, although that is still in a fledgling state…

PEN Int’l President Homero Aridjis

“The so-called “humanitarian war” in Serbia and Kosovo provoked another war among intellectuals who were for or against NATO’s armed intervention,” he said. “After the Russian Revolution and the fascist and Nazi movements which lead to World War II and the dictatorships of Hitler and Stalin, and after dozens of petty or powerful dictators who tortured and murdered writers and journalists in many countries and continents throughout the twentieth century, this seems to be the first war since the fall of the Berlin Wall which has pitted writers against each other. Peter Handke, Susan Sontag, Salman Rushdie, Bernard-Henri Levy, Andre Glucksmann, Norman Mailer, Harold Pinter, Mario Vargas Llosa, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Jose Saramago and Alexander Solzhenitzyn, among others, came down strongly on either side. Various writers from the Balkan region gave their views in Bled (at PEN’s Peace Committee meeting) at the end of May…

“The theme of this congress is to bid farewell to the 20th century before it is over, to say goodbye to this century which dawned upon a world ruled by a host of imperial and colonial powers such as Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria, Russia and the Ottoman Empire. This century also witnessed the rise and fall of the Third Reich and the Soviet bloc,” he added. “The age of empires has apparently drawn to a close, giving way to dominance by individual countries, economic unions and multinational corporations, and by new alliances, including the United Nations. NATO, the European Union and the World Trade Organization. International PEN, founded in London in 1921, is probably one of the century’s oldest international alliances and will move into the 21st Century firm in its defense of freedom of expression and human rights of professional wordsmiths…

“Here in Warsaw we are only 300 kilometers from Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest of the Nazi extermination camps. Although many writers and poets have borne witness to the Holocaust, and it has been described in countless chronicles, documentaries and books, it will never create to cause us indescribable horror, nor will we ever be able to grasp it fully…

“This year people around the world will perform the collective ritual of pondering over the last ten centuries. The media will bombard us with lists of events accompanied by examinations of conscience, and natural disasters, violations of human rights, social conflicts and environmental destruction will be weighed against advances in public health, literacy and communications, the spread of democracy, and the works of writers…

“As for PEN, what I would like to see accomplished at the start of the 21st century is the creation of more Centers in Africa, Asia, and Latin American, and the strengthening of existing Centres on those continents and on Eastern Europe so that PEN may become a truly global organization…”

Visit to Krakow during 1999 PEN International Congress

This vision has been in part realized as PEN has expanded in the 21st century on all continents and an Exile Network institutionalized years later in partnership with the International Cities of Refuge Network. PEN has continued to advance its work in freedom of expression through the Writers in Prison Committee and its work with women through the Women’s Committee and with minority languages and translation through the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee. As for peace, PEN is not a “peace organization” though it has a Peace Committee (see PEN Journey 14), but it doesn’t have tools to bring about peace on a global scale. However, debate and discussion among its members has had impact (see PEN Journey 6) since writers are the expounders of ideas which work for ill or good.

Adam Michnik, Photo credit: Albert Zawada/Agencja Gazeta

At the Warsaw Congress delegates visited Gazeta Wyborcza, the daily newspaper whose editor Adam Michnik was one of the intellectual authors of the Solidarity Movement that eventually led to the overthrow of the Communist hold on Poland. The paper in its rabbit-warren offices if memory recalls correctly, was the first independent newspaper published outside the communist government’s control since the late 1940’s. During the visit Adam Michnik offered to have Gazeta write an article about one of PEN’s cases in Chile of an arrested publisher and editor; however, shortly after the Congress, the publisher was released.

Through most of the years of the Cold War Polish PEN had managed to operate within the PEN family. After the Communist regime fell, Polish PEN was particularly effective in working on behalf of writers who were imprisoned under communist dictatorships such as in Vietnam.

PEN itself was reshaping into a more democratically governed organization. At the Warsaw Congress the first Executive Committee (later called the Board) was elected. After the 1998 Helsinki Congress, a call went out for nominations and a vote for PEN’s first Search Committee whose task was to facilitate the nomination of qualified candidates. Twenty-four people received at least two nominations for the Search committee, and five people were elected by postal vote: Kjell Olaf Jensen (Norwegian PEN), Lucina Kathman (San Miguel Allende PEN), Eric Lax (USA West PEN), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN) and myself. We met as a committee only once in person at the Warsaw Congress; most business was conducted via conference calls, faxes and some email, though not everyone had email at that time. We helped set out guidelines for the Search Committee and worked to assure there was a wide and diverse range of candidates for the first Executive Committee of PEN.

Fourteen candidates from every continent were nominated for the seven positions on the Executive Committee which was elected at the Warsaw Congress. PEN’s first Executive Committee included Carles Torner (Catalan Center), Vincent Magombe (African Writers Abroad Center), Gloria Guardia (Colombian Center), Niels Barfoed (Danish Center), Fawzia Assaad (Swiss Romande Center), Takashi Moriyama (Japanese Center), Marian Botsford-Fraser (Canadian Center). The four with the most votes received three-year terms and three members received two-year terms; thereafter elections occurred on a staggered basis.

PEN had decided against requiring regional representation on the board though hoped this might occur naturally. The first Executive Committee represented centers in Europe, Asia, Africa and North and South America. Now the challenge was for everyone to figure out how to operate in the 21st Century…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 23: Nepal–WIPC Crossing the Bridge Between People

PEN Journey 21: Helsinki—PEN Reshapes Itself

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

In the old days, at least my old days, the Vice Presidents of PEN International sat in a phalanx on a stage while the Assembly of Delegates conducted business—revered writers, mostly white older men, along with the President, International Secretary and Treasurer of PEN in the center. If the Assembly business wore on, it was not unusual to see one or two of them nodding off. The role of the Vice Presidents was to provide continuity—many had been former PEN Presidents—to provide wisdom, contacts and gravitas. The designation was for life.

But times were changing. For instance, I had recently been elected a Vice President. I was a woman. I’d served PEN in several positions, including president of my center, founding board member of the International PEN Foundation and International Writers in Prison chair; I was a writer, though not of international renown, and at the time I was relatively young. I had been nominated by English PEN whose General Secretary thought it was high time more women sat on that stage. I didn’t relish sitting on a stage, but I was honored to hold the position. The Helsinki Congress in 1998 was the first when Vice President was the only role I had. I don’t recall if there was a stage at that Assembly. The fun was that I didn’t have to do anything. I could float between committee meetings, offer comments when relevant, wisdom if I had any and be called upon for whatever insight or experience or task might serve. (Traditionally the Congress organizers paid for the Vice Presidents’ registration and hotel, but from the start I chose to cover my expenses as a way of contributing to PEN. The expense of Vice Presidents attending was growing more and more difficult for the host centers; on the other hand many Vice Presidents wouldn’t be able to attend otherwise.)

Program for 65th PEN International Congress in Helsinki, Finland

At the 65th PEN Helsinki Congress held at the Marina Conference Center on the waterfront, a short walk from the city center, delegates and PEN members from 70 centers around the world gathered. The Congress’ theme was Freedom and Indifference. My memories are of meals on the water with colleagues, of eating fish and mussels and walking among old and very new buildings, visiting the architecturally stunning Contemporary Art Museum and other cultural excursions I often didn’t have time to attend when chairing the Writers in Prison Committee.

At the Congress I could even sit in on a few of the literary sessions which included abstract topics such as Where Does Indifference End and Tolerance Begin?—The Role of the Intellectual in Contemporary Society; Eurocentrism and the Global Village; The Cultural Gap Between East and West; The Ambivalence of Otherness: Identity and Difference; Crime Literature Portraying the Society; On Cultural Creolisation (mixture) and Borderlands. I confess reading those topics now stirs memories of sleepy academic afternoons, but the writers presenting included some of the engaged and engaging writers of the day, including Wole Soyinka, Caryl Phillips, Andrei Bitov and many Finnish and Scandinavian writers such as Sweden’s Agneta Pleijel.

At the Congress I still concentrated on the work of the Writers in Prison Committee which former Iranian prisoner Faraj Sarkohi attended. The year before he had been a main case for PEN, imprisoned and tortured and threatened with execution. In introducing his presence to the Assembly of Delegates, PEN President Homero Aridjis noted that PEN members could take satisfaction in having played an important role in obtaining his release. Sarkohi had managed to get a passport and was now living in Europe where he’d resumed his literary and journalistic activities.

Moris Farhi, the new WiPC Chair, introduced Sarkohi to the General Assembly of Delegates where Sarkohi said he owed his life and freedom to the international movement initiated by PEN both in the London headquarters and in the PEN centers around the world. For the first time in 20 years the Iranian government had been forced to release someone they had wanted to kill, he said. His release demonstrated to other writers in Iran that release was possible even if the government wanted to execute them. Sarkohi had briefly spoken with another PEN main case in prison who told him he was no longer worried, knowing now about the international support he was receiving.

Sarkohi explained that writers were considered by the despots in Tehran to be guilty because they worked with words, because they tried to discover and express in words different aspects of truth. It was believed writers made magic, he said. Everyone knew the magical power inherent in words so the writers were arrested. The government forced them to deny themselves, to accept false charges, and in this way they killed writers mentally. When a writer was forced by physical and mental torture to deny himself, his ideas and his work, his power of creation died, and he was killed as a writer. When Sarkohi was in solitary confinement, he remembered the way in which those suspected of magic were treated in the Middle Ages. People were arrested and burned and told “If you live, your magic powers are proved and we kill you. If you die, it is established that you do not have magic powers.’—but you were dead anyway. Writers were regarded as the new practitioners of magic in this century and that treatment by tyrants and despots was that of the Middle Ages.

Sarkohi described how he and colleagues who were still in prison had issued a new Charter, inspired by the PEN Charter, in which they protested censorship, both by the government, self-censorship and by the public such as groups which beat up a writer in the street. The Charter also demanded the right for writers to organize an association, something not permitted in Iran. He worried now about the fate of his colleagues in Iran because five years ago when writers published a Charter and sent the text abroad, the government had reacted and killed a famous translator and dumped his body in the street and murdered a famous poet in his home.

Sarkohi noted that German PEN and other PEN centers had prepared a resolution for the Congress making it clear to the Iranian government that International PEN was watching the fate of Iranian writers so they would know before they arrested or killed someone that Iranian writers were supported. He believed that support let all the world see that writers were not alone.

L to R: Mansur Rajih from Yemen, one of the first ICORN guests in subsequent years, and Iranian writer Faraj Sarkohi, former WiPC main case at PEN International’s 65th Congress in Helsinki, Finland, 1998

While the Helsinki Congress focused on the traditional work of PEN and its Committees, it was also a watershed Congress addressing the structure and governance of PEN. The Ad Hoc Committee, elected at the previous congress in Edinburgh (see PEN Journey 20), had examined the draft of revised Regulations and Rules and presented a final draft for the Assembly’s adoption. The revised Regulations and Rules were the product of two years’ work and consultations among centers. These were the first amendments to the Regulations of PEN since 1988 and the first major revision since 1979.

International PEN’s reform to provide more democratic decision-making, more communication between the International and the Centers and more transparency was not an entirely smooth transition and reflected a larger global trend at the time among the 100+ nationalities represented in PEN.

At the Congress a new International Secretary—Terry Carlbom from Swedish PEN—was elected as the only candidate, Peter Day, editor of PEN International magazine, having stepped down from consideration because of health reasons. The former International Secretary Alexandre Blokh, who had served for 16 years, didn’t attend the Congress, but was elected a Vice President and returned to subsequent Congresses.

Marian Botsford Fraser of PEN Canada, representing the Ad Hoc Committee, presented the new proposed Rules and Regulations, noting that they were “the nuts and bolts or the strings and hammers of a piano or the engine of a car or mother board of a computer. In any case their workings were unfamiliar to most writers,” she said. “It was as if we had been asked to rebuild the engine of a 1979 Audi, a vehicle renowned for the complexity of its construction. Frankly I can think of only one more difficult assignment for nine writers and that would have been to collaborate on the writing of a novel.”

She noted that the Committee of nine was a diverse collection of individuals with the wisdom that democracy sometimes magically bestowed upon its practitioners. The Edinburgh Assembly had chosen a group of people who represented the linguistic, cultural and geographic diversity of PEN and who brought to the table individually and collectively their commitment to the history and the future of PEN, their desire to remain true to the spirit of the Charter of PEN and to the identity of PEN as first and foremost an organization of writers working together to protect language, literature and the fundamental human right of freedom of expression. “We brought to the process different and strongly held views on how to make the regulations that we were charged with drafting embody those principles, how to create a structure that would become the foundation for the future of this organization,” she said.

She thanked certain Ad Hoc members, who in fact did seem to have some knowledge of the workings of a 1979 Audi and added special thanks to Administrative Director Jane Spender “who took the whole mess of scribbled bits of paper, half sentences, cryptic clauses, clearly articulated ideas and sometimes incoherent good intentions back to London, and through another process of consultation and discussion and writing and rewriting was able to turn all of this into two documents that were sent to all Centers as Draft Regulations and Rules.” Homero Aridjis, the new International PEN President, also participated in this task along with the Ad Hoc Committee.

As I read through the minutes of the Helsinki Assembly, I recalled the tensions that arose, particularly around single words such as “a-political”—after all we were an organization of writers where words and translation of words mattered—and around events that had happened off stage. Changing the way a 77-year old organization worked was perhaps more like shifting from an Audi into an SUV which could hold more people, handle more difficult terrain but also consumed more fuel and energy. But metaphors aside, after debate and discussion, agreement was ultimately achieved.

The most important change was the move to form an Executive Committee that would be the main implementing body for International PEN, a step agreed by most all Centers who chose to participate in the process. Instead of government by a small executive of the President, International Secretary and Treasurer between the Assembly of Delegates’ meetings, an Executive Committee of seven members drawn from the centers around the globe and elected for three-year terms (and up to six years) would operate along with the three executives of PEN. The election for the first Executive Committee was to take place at the 1999 Congress in Warsaw. Until then the Ad Hoc Committee would continue to function and also act as a Selection Committee to assure qualified candidates were put forward.

Details of this new structure were modified over the next twenty years. The Selection Committee evolved into an elected Search Committee to assure qualified candidates were proposed for the various offices and to gather their required papers. The Search Committee was not set up to be a guardian council or an arbiter of candidates, but a facilitator for the process. In 2005 an Executive Director was added to the equation. As with any organization, PEN keeps growing and changing, but the essential structure to broaden and democratize governance of this global organization was set in place in 1998 in Helsinki. I’m not sure what vehicle I would compare PEN to these days, probably not a finely tuned Audi, but it continues to drive.

As for Vice Presidents, that office was not changed during this watershed period of reform, but over time, PEN changed the role of Vice Presidents and designated the ex-Presidents as Presidents Emeritus instead and divided the Vice Presidents into two equal categories with twelve in each: those elected for “service to PEN” and those designated for “service to literature;” the later included internationally renowned writers and Nobel laureates such as Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison, Svetlana Alexievich, Orhan Pamuk, Margaret Atwood, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, J.M. Coetzee.

When I became International Secretary (2004-2007), the Executive Committee (now called the Board) and I proposed, and the Assembly agreed, that Vice Presidents’ terms should be limited, at least in the category of service to PEN—ten years or sometimes twenty—then most would move to emeritus status. It took another ten years before this change was implemented.

These are arcane details but illustrate PEN as an organization striving to keep those experienced engaged at the same time keep the organization unencumbered so it can grow and bring in new ideas and talent. It is a vehicle constantly re-tooling with the Charter as its base and a body of creative members whose greatest talents are not necessarily in rules and regulations yet who respect their necessity. Vice Presidents Emeritus, as I now am, are invited to the Congresses and show up and are still sought out for the bit of history we know and for the bits of wisdom we might offer from our experience and for continuity. We knew PEN in the days of the Audi, though even then it was perhaps not so finely tuned, I think, but it got from here to there across the globe as it still does.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 22: Warsaw—Farewell to the 20th Century

PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest

I begin with the memories…

Castle Rock and Edinburgh Castle in Edinburgh, Scotland

—the imposing walls around Castle Rock which stands above the city of Edinburgh and dates back to the Iron Age,

—the 12th century castle/fortress inside,

—the Old Parliament building,

—the New Parliament building where we sat in high-backed theater-style seats in an arena,

—the dorm room residence inside Pollack Halls where we stayed at Edinburgh University near the city center, beside an extinct volcano,

—the receptions at Parliament House and Signet Library and the City Arts Center where there was never quite enough food for the overly hungry delegates who descended upon the platters,

—the UNESCO seminars on women and literature, including my paper The Power of Penelope,

—and elections, so many elections and speeches—three candidates for Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) Chair, seven candidates for International PEN President, nine Ad Hoc Committee members as precursors to a new governing board for International PEN.

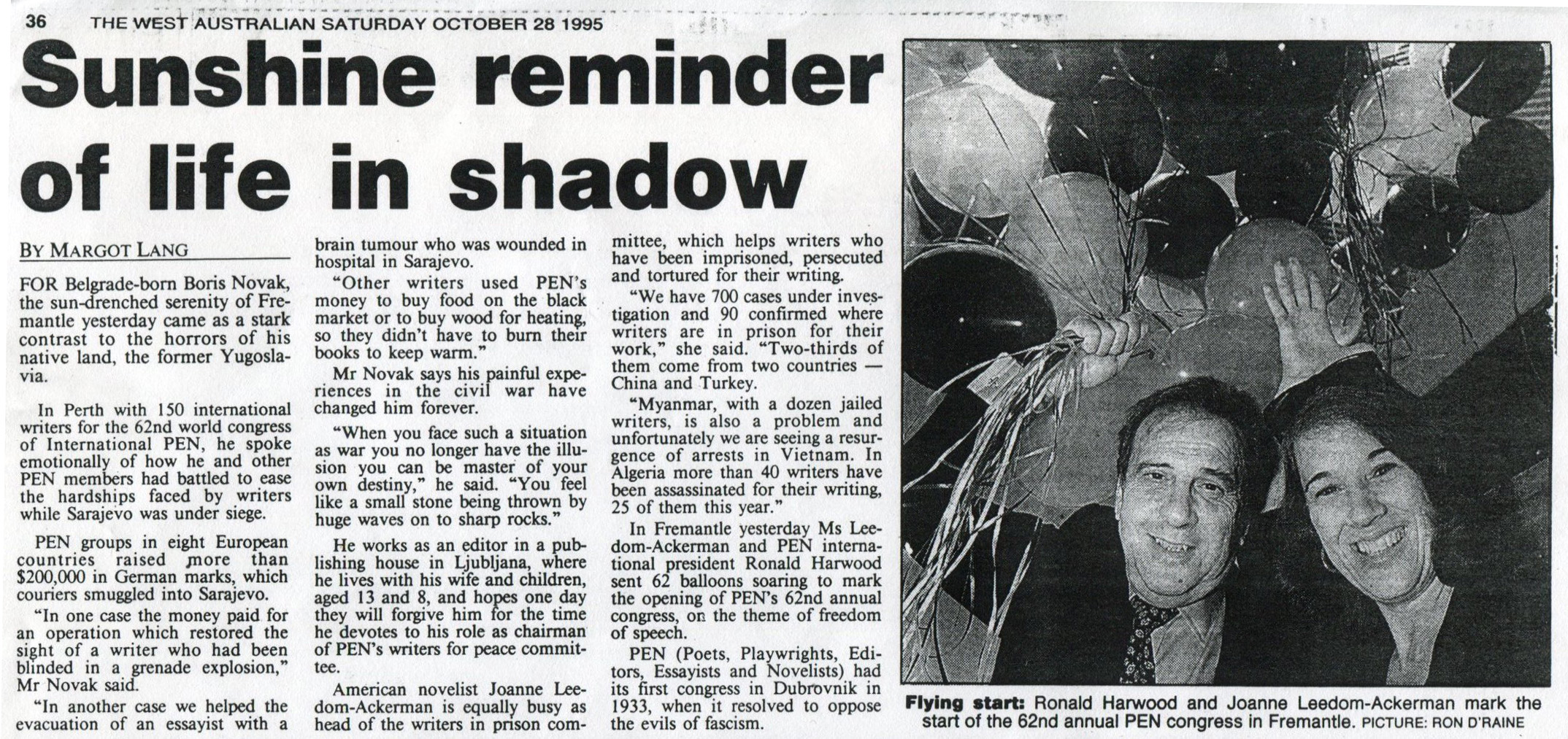

These were the first contested elections I remembered in International PEN. A wider democracy was spreading with ballots and speeches. I also remember the tension and the occasional flares of anger, and the effort to hold us all together and ultimately the confident results and the determination to move forward in unity. International PEN President Ronald Harwood warned that while PEN badly needed to democratize “power” so it wasn’t too centralized, residing in the hands of a few, the delegates should not make the struggle personal and should go forward with a sense of humor. We were an organization of writers, not the government of the world, he admonished, warning members not to confuse bureaucracy with democracy.

—I remember the trip to Glasgow where a few of us had a stimulating visit and tea at the home of James Kelman (Booker Prize winner How Late It Was, How Late) who had been with us in the protests in Turkey a few months before (see PEN Journey 19) and the old Mercedes tucked in the garage in the working class neighborhood.

—And the Edinburgh International Festival, including the Edinburgh Book Festival, happening simultaneously all around us.

—And finally the exquisite August light in Scotland.

Program for 1997 PEN International Congress

I begin with memory then plunge into the minutes and documents of the 64th PEN Congress August, 1997 when delegates from 77 PEN centers around the world gathered. The Congress theme Identity and Diversity posed the questions:

In the contemporary world there are intense pressures, political or commercial, deliberate or unconscious, towards an imposed uniformity. One example is the effect on language. Indigenous languages, which embody particular traditions and experience, are in many countries under threat of displacement and extinction. These tendencies are inimical to literature which depends on its local personality for its color and effectiveness even when it achieves universal significance.

On the other hand, we live in an inter-dependent world where peace, prosperity and ultimately even survival, require co-operation. This international co-operation may be assisted by the use of a few languages which are widely understood. International exchange of the appropriate kind can also bring cultural enrichment.

How can these apparently contradictory objectives of diversity and co-operation be reconciled? Does literature have a role in this respect?

As with most abstract themes and questions, there is no simple answer, but the theme was a pivot, in this case both in the literary sessions and inadvertently in the business of PEN as the organization sought to restructure itself. Because this was my last congress as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee, the work of that Committee absorbed my focus. My two reports—one the official printed International PEN Writers in Prison Committee report and the other an address to the Congress—observed, and in a fashion related, to this theme:

[Written report:]

PEN Writers in Prison Committee Report, 1997

Tension between the individual and the state underlies the work of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee. In some countries constitutions and governing principles are set out to protect the individual from the state, but in the majority of countries which PEN monitors where writers are imprisoned, threatened or killed, the state is organized to protect itself from the individual. Whether those countries be totalitarian regimes like China, Myanmar/Burma, Syria, Vietnam, Cuba or democracies like Turkey and South Korea, when the state holds itself superior to the rights of its individual citizens, freedom of expression is seen as a threat to stability rather than a sign of stability.

In 1997 the Writers in Prison Committee has defended individual writers in at least as many of the new and older democracies around the world as in totalitarian states. Since 1990 dozens of nations in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia have restored or initiated multi-party democratic elections. The turn to the democratic process initially freed up restrictions on writers and journalists in many countries. However, after the first flush of these freedoms, after dozens of independent publications sprang up in Argentina, Belarus, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Russia, Sierra Leone, Zambia, etc., tensions mounted between the individual voice and the state. Restrictions and press laws followed, and writers once again found themselves facing prison terms on such charges as “insulting the President”, “writing derogatory statements against the government and government officials”, and “seditious libel.”

In some states like Sierra Leone harsh restrictions on the media preceded coups and the loss of democracy. Reporting restrictions and brief detentions of journalists enforced by the crumbling Mobutu government in Zaire (now Congo), did not serve to protect it from its eventual collapse. Earlier this year the political crackdown in Belarus was preceded by severe censorship and curtailment of publications. The collapse of the government in Albania was followed by severe restrictions on publications and attacks and death threats on journalists and writers.

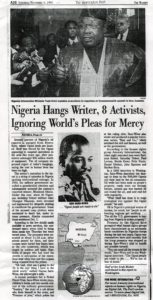

When a coup occurs and democracy fails, the consequences for free expression are usually disastrous as has been seen in Nigeria where journalists continue to serve lengthy prison terms and are arbitrarily detained, sometimes for months without charge. Another instance of a threat to freedom of expression in Nigeria is that of PEN member and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka who is among 12 dissidents charged in Nigeria this year with the capital offense of treason. Soyinka remains free outside the country but is certain to be imprisoned if he returns.

Pressure on writers and the media continued or increased in many new and old democracies, including Algeria, Argentina, Bosnia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgystan, Mexico, the Palestinian authority, Turkey, Uganda and Zambia. Pressures took the form of legislation which required publications to obtain government licenses and approval and/or required journalists to have state-approved credentials. Pressure also took the form of arrest, arbitrary detention and death threats…

When democracy fails, there are hosts of reasons embedded in history and politics. Curtailment of free expression is not necessarily the precipitating cause, and curtailment of free expression does not always lead to failure of democracy. However, repression of the written word and of the writer remains at the very least a symptom and often a warning light that political failure lies ahead…

The report goes on to outline situations of individuals under threat. Reading these reports is reading a political history of the time, told through the circumstances of individual writers. One of the highlighted cases at the Congress in 1997 was that of Iranian writer Faraj Sarkohi who’d signed a petition calling for freedom of expression, along with 134 other Iranian writers. Sarkohi had been kidnapped by the Iranian secret service while on his way to visit family in Germany; he was tortured and threatened with execution. Because of the worldwide protests by PEN and others, he was eventually released the following year and sent into exile.

Visiting the WiPC meeting in Edinburgh, Egyptian professor Nasr Hamed Abu-Zeid, a leading liberal theologian on Islam, told his story of being declared an apostate for his research and forced to divorce his wife, also an academic. They had fled Egypt where apostates could be killed. Şanar Yurdatapan, the Turkish activist who’d organized the Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression which many of us attended earlier that spring, had just been released from prison and also spoke to the meeting. The cases of Sarkohi and Abu-Zeid and Şanar were among 700 on the WiPC records.

[Address to Assembly of Delegates:]

After four years chairing International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, I’ve come to appreciate the simplicity of the Committee’s mandate and the complexity of its execution. To defend the individual’s right to free expression is to defend not only the essence of literature but also a cornerstone of free society. Our defense begins with the individual writer, but inevitably we are caught in the movements of politics and history where individuals struggle to shape, divert or oppose the tides. One of the most significant developments in the past few years has been the expansion of multi-party democracies across the globe, a development that at first glance would signal progress for free expression. However, from our work we have seen that democracy takes more than a polling booth and a list of candidates on a ballot to come to fulfillment. Freedom of the written word is essential for a democracy to work over the long term, and attacks on this freedom usually foreshadow larger repression and even the failure of the democracy itself.

This year PEN has seen repressive laws enacted and/or writers arrested and killed in the new and old democracies of Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Belarus, Bosnia, Cambodia, Cameroon, Croatia, Ethiopia, Egypt, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Russia, Palestinian territory, Peru, Sierra Leone, South Korea, Turkey, Zambia. Many governments have passed or tried to pass laws to bring publications under their control through licensing and government-approved credentials. These laws have been followed by the arrest of writers.

Repression remains the most severe in totalitarian states such as China, Cuba, Iran, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Syria, Vietnam. China continues to imprison more writers for longer periods of time—over 70 individuals, many serving 10-20 years—than any other country. Many of the writers who were imprisoned during Tiananmen Square have been released in the past two years, but others have taken their place. The Writers in Prison Committee is watching with great concern legislation which could lead to restrictions on writers in Hong Kong as China takes over. The Committee is also following closely the continued repression in Myanmar (Burma) where prison conditions remain harsh and at least 25 writers remain behind bars, many with sentences exceeding ten years…

Many of the cases in Africa this year came from new democracies struggling with issues of free expression, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Zambia. The military dictatorship of Sani Abacha in Nigeria continued to occupy the focus of many PEN centres who worked on behalf of writers still in prison. Protests from a number of PEN centres assisted in the release of two Nigerian writers…Our Committee heard a statement from PEN main case Koigi wa Wamwere from Kenya, where riots have broken out after calls for democratic reform. Centres around the world have lobbied for his release, and he is now out on medical bail, and the Writers in Prison Committee has assisted his return to Norway where he is living. He sent a message thanking PEN for its work on his behalf. He writes, “When dictators arrest writers, they guard them with more guns and soldiers than they guard enemy armies in captivity. Dictators fear ideas and writers more than they fear guerrilla armies. Afterall they know that without ideas even guerrilla armies would wither away and die…”

In Latin America PEN continued to protest this year the imprisonment and detention of writers in Cuba. This spring the Writers in Prison Committee issued its report on its Cuba trip last fall, focusing on dissident writers who often had to choose between prison and exile…In Peru, though legislative and judicial reforms have occurred in the last years, at least 11 writers there have reported threats and/or attacks from both governmental and non-governmental sources, and sixty writers and journalists have reported death threats or attacks in Argentina…

The Writers in Prison Committee continues to work closely with freedom of expression organizations around the world, sharing our research and disseminating via the internet so that when a writer is arrested as far away as Tonga, the King of Tonga suddenly found himself receiving faxes from all over the world.

Over the years the political tides have shifted, but members’ work on behalf of individuals and the friendship of writer to writer remain even after the writers are released. This year we saw releases in Cameroon, China, Cote d’Ivoire, Cuba, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Kuwait, Maldives, Myanmar (Burma), Nigeria, Peru, and Russia. On occasions we have gotten to meet and know the individuals personally. This year when the Nigerian government picked up Ladi Olorunyomi, the Writers in Prison Committee was quickly alerted. A number of us had had the opportunity to meet with her husband Dapo, a prominent editor and dissident now living in exile in the United States. Isabelle Stockton, our Africa researcher and I spoke in the morning, and she called him to gather more details. When I phoned him later in the day, he said, “I was going to call you, but before I could, PEN was already calling me.” As soon as we determined that Ladi Olorunyomi had not been charged with a crime, had no access to lawyers and was not allowed to see her family, we put out a Rapid Action to our centres and shared the information with other freedom of expression organizations all around the globe. During her almost two months in captivity we were able to monitor the case, share information, and hear with great relief when this writer and mother was finally released.

Dapo, who had secretly fled Nigeria a year earlier lest he be imprisoned, wrote PEN, “Thank you for everything! I am very grateful, but I lack the words, appropriate enough to convey my gratitude…to our good friends at PEN International.”

The business of PEN throughout the year and at the annual Congress also included the work of the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women’s Committee, Peace Committee, the growing activity of the Exile Network and the literary sessions. The UNESCO seminars on Women’s Cultural Identity linked to the seminars on Literature and Democracy at the Guadalajara Congress the year before. In many parts of the world women still did not have full democratic rights. Significantly, in Latin America only 10% of books published were by women, and in Africa it was as few as 2%. But I must leave others to elaborate these activities.

At the 64th Congress results of the many elections yielded the next group of leaders who would take the organization into the last years of the 20th Century and into the transformation of governance. At the Congress Ronald Harwood was elected a Vice President as I had been at the previous Congress and as such we stayed connected and in the wings for the changes ahead.

Election results of the 64th PEN Congress:

Homero Aridjis

Seven candidates stood for the presidency from Europe, Africa and the Americas though one dropped out. Homero Aridjis of Mexico, well-known poet, journalist and diplomat, was elected the next President of International PEN.

Moris Farhi

Novelist Moris Farhi, former chair of English PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee, was elected chair of the WiPC. The two runner-ups Louise Gareau-Des Bois (Quebec PEN) and Marian Botsford Fraser (PEN Canada) agreed to serve for a year as Vice Chairs. In 2009 Marian Botsford Fraser was elected chair of WiPC and served till 2015.

The new Ad Hoc Committee elected at the Congress included Marian Botsford Fraser (Canada), Takashi Moriyama (Japan), Boris Novak (Slovenia), Carles Torner (Catalonia), Jacob Gammelgaard (Denmark), Vincent Magombe (Africa Writers Abroad), Gloria Guardia (Colombia), Gordon McLauchlan (New Zealand) and Monika van Paemel (Belgium). This committee was charged with considering all the restructuring proposals and preparing a draft for discussion and adoption by the Assembly of /Delegates at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. The Ad Hoc Committee was also tasked as a Nominating Committee to search for a new International Secretary. Alexander Blokh, re-elected for another year as International Secretary, planned to step down at the 1998 Helsinki Congress. Little did I know nor aspire to take on that role six years later.

New PEN Centers voted in at the Edinburgh Congress included Cuban Writers in Exile, Somali-speaking Center, Sardinian PEN Center, and a reconstituted Mexican PEN Center.

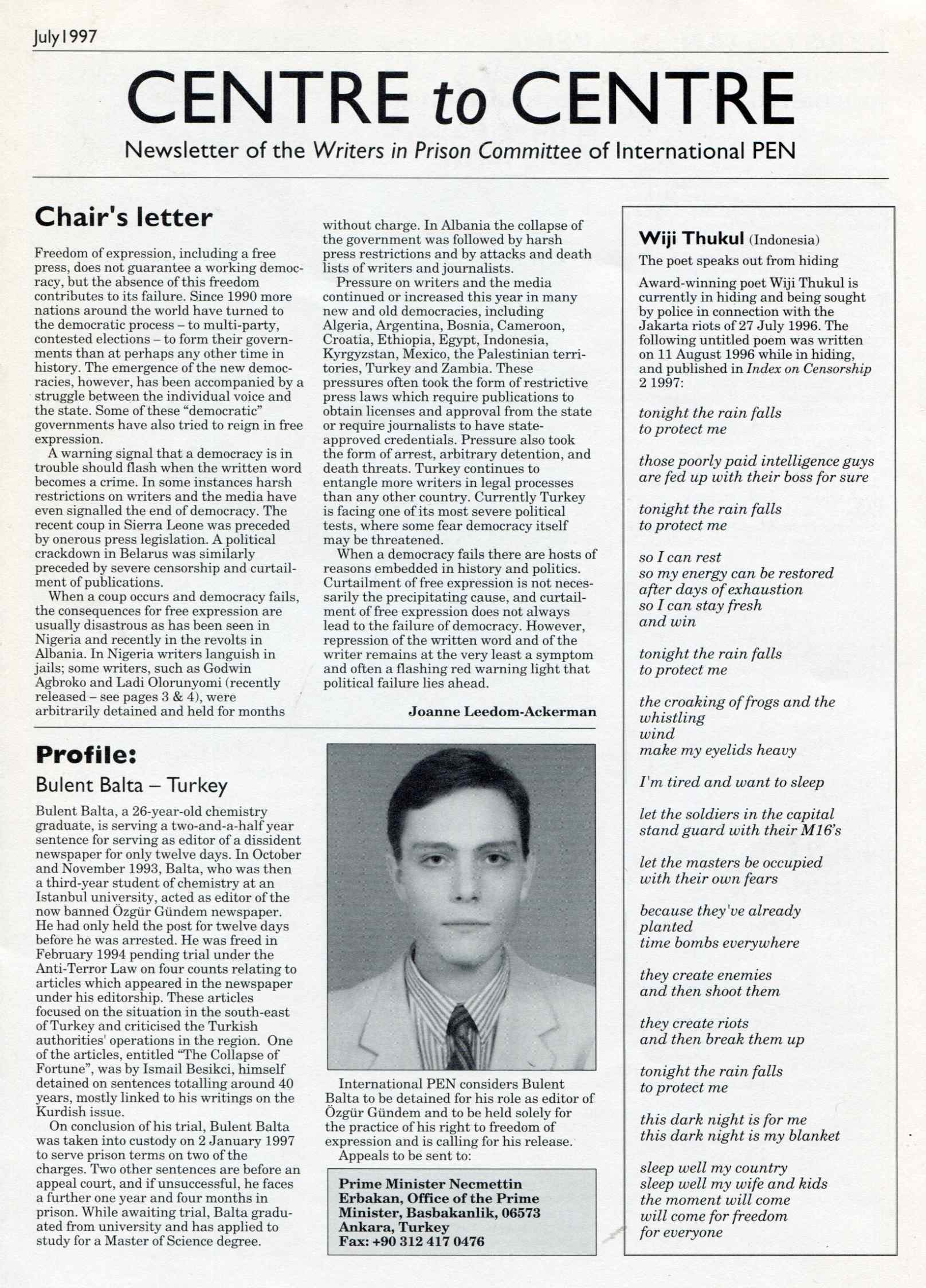

PEN International’s Writer in Prison Centre to Centre newsletter, July, 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 21: Helsinki–PEN Reshapes Itself

PEN Journey 19: Prison, Police and Courts in Turkey: Initiative For Freedom of Expression

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

We sat on the ferry drinking strong Turkish coffee then handing over the emptied cups to a woman who read fortunes from the pattern of the leftover coffee grounds. As we huddled in the wind off the Sea of Marmara en route to the prison in Bursa, we speculated who among the passengers was following us. We were assured we were being followed.

Program for Initiative for Freedom of Expression Gathering, March 1997

I came to Turkey in March 1997 as the returning Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (WIPC) (PEN Journey 18). I was heading a delegation of 20 PEN members from 12 countries. We’d arrived to support Turkish PEN, the Turkish Writers’ Syndicate, the Literary Writers Association and the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in the first Gathering in Istanbul for Freedom of Expression. We had signed on as “publishers” to an abridged version of the book Freedom of Expression. The original book included essays by those who were in prison or facing charges for their writing, particularly former president of Turkish PEN, the prominent novelist Yaşar Kemal. He was tried for an article he’d published in the German magazine Der Spiegel. (PEN Journey 17). Headlined “Campaign of lies,” the article called out the government for its human rights abuses, particularly its treatment of the Kurds.

Arthur Miller letter to Yaşar Kemal, March 1997

Bearing a letter from Arthur Miller, who knew Kemal and had himself come to Turkey with Harold Pinter in solidarity a dozen years before, I was among the 141 “foreign publishers” of the booklet Mini Freedom of Expression. This book contained a paragraph from each article published in the larger book. We joined the 1080 Turkish “editors” of the larger volume who included writers, theater actors, politicians, painters, cinema actors and directors, cartoonists, musicians, trade unionists, academics, lawyers, architects and others. The Turkish Penal Code made it a crime to re-publish an article that had been defined as a “crime” so that the publisher as well as the writer was charged.

The “publishers” had presented themselves before the State Security Court and faced charges of “seditious criminal activity.” After questioning the first 99 people, the prosecutor demanded the accused be tried under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law and Article 312 on “disseminating separatist propaganda.” After six months only 185 of these individuals had been questioned and brought to trial. If these individuals were given the usual 20-month jail sentence, that would mean ten popular television programs would have to be canceled because their stars or directors would be in prison; five series would have to find new stars and change their story lines. The media would lose over 30 well-known journalists; 15 popular columns would be left blank. Eight professorial chairs would be left vacant, and universities would require new teaching staff. Theater stages and film sets would require many other artists, directors, musicians, etc., and 20 new books about prison life would be added to literature if every author wrote.

Turkey already had over 200 writers either in prison or entangled in legal processes, more than any other country. This protest initiative was unique and creative. The challenge to the court was to bring charges against so many. The State Prosecutor had dropped charges against the foreign participants on the grounds that he wasn’t able to bring us to Istanbul for questioning though the Turkish citizens who had prepared and distributed the booklet could be tried. The organizer of the initiative Şanar Yurdatapan suggested we come to Istanbul and challenge the prosecutor. Though PEN members were willing to come to support their Turkish colleagues, no one wanted to end up in a Turkish prison.

“No one will go to prison,” Şanar assured. The prosecutor had to act within six months, and even in the unlikely event charges were brought, we’d go home before a trial, and there was no extradition from the US, UK and many other countries because no such “offense” existed under their laws. Unlike organizations such as Greenpeace, PEN was not a direct action organization. PEN dealt in words, protest letters, diplomacy, meetings, on occasion candlelight vigils outside embassies and stories in the media. But Şanar, who was a song writer, civic activist, not a PEN member, instinctively understood the dynamics of nonviolent direct action and understood how to get attention and make the point that the Turkish laws were unjust and unfairly administered.

On our first day, which was Women’s Day, we joined the Saturday Mothers’ rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members. The gathering had been held every Saturday for a year and a half at Galatasaray Square, ten minutes from our small hotel in Taksim. The crowd of mothers and children held pictures and signs of their loved ones, mostly Kurds, who had been taken away, assumedly by the government and likely killed. On the edges of the crowd police in riot gear gathered but didn’t interfere. Meeting at Galatasaray Square is now banned for Saturday Mothers by the Ministry of Interior since August 25, 2018. They still keep the rally at Human Rights Association branch in one of the back streets.

Saturday Mother’s Rally of relatives of the disappeared who gathered every Saturday seeking information on their family members.

From there a number of us went to a women’s rally where hundreds of Kurdish women in traditional dress marched with banners shouting, “We are mothers; we are for peace! Mafia is in Parliament; students are in prison.” Along the route men cheered and dozens of police lined the road frisking and checking bags. This was the last weekend of a 40-day protest all over Turkey. At 9pm every night people around the country turned out their lights or blinked their lights and shouted out their windows and in the street, “Go Away!” in protest over the government. The idea was that people would have one minute of darkness to get years of light. At dinner that Saturday evening we watched as the streets filled with shouting and the lights in restaurant blinked on and off.

Women’s Day march of Kurdish women with police positioned along the route.

The trip to Istanbul was my first of what would turn out to be dozens of visits to Turkey over the years for PEN, for other organizations, and for family. In 1997 the times were tense; soldiers with their weapons and machine guns were stationed at the airport; armed police were on the streets; we were followed; the phones at the hotel were likely tapped. It was difficult to imagine then that it would get much better in the following decade as it did and then much worse in recent years. I’m not sure today we could hold such a gathering with confidence.

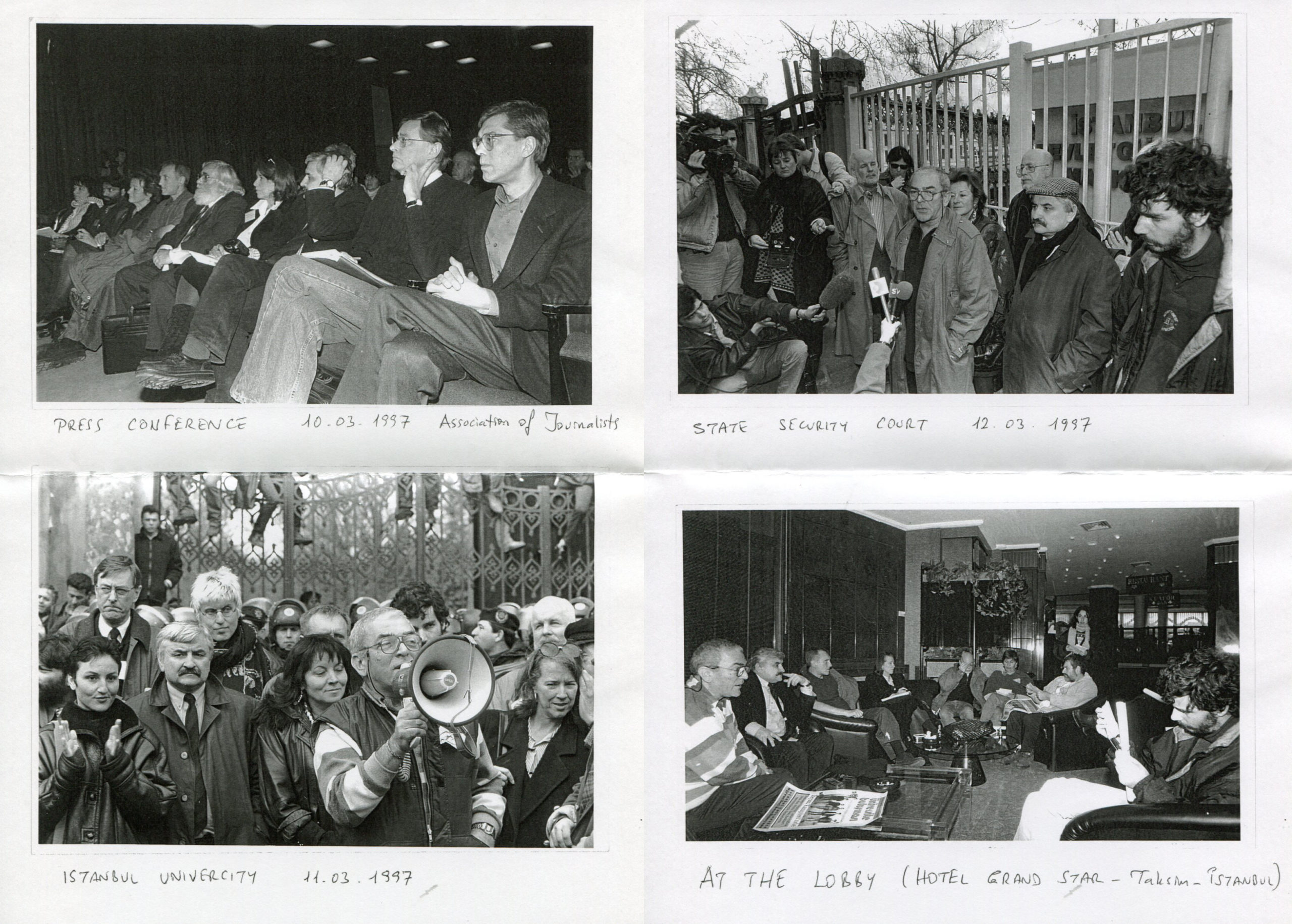

Throughout our visit we were covered by the press, including two visits to the State Security Court. In 1997 the legal way to meet publicly was to hold a press conference so we spent our days in press conferences, including one at the Journalists Association. Because I was Chair of the WiPC, I was often the one explaining why we were there. I emphasized that we had come out of respect for Turkish literature and writers. We had not come to break Turkish laws; we did not consider editing a book a crime. We were there to uphold the international covenants that Turkey had signed, approved and became a party to: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 19), Article 19 of the UN Convention on Civil and Political Rights and Article 90 in the European Convention on Human Rights. We noted that Article 90 in Turkey’s own Constitution declared that no law should supersede these international covenants.

Our PEN delegation included representatives from Canada (Quebec), Finland, Germany, Holland, Israel, Mexico, Palestine, Russia, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States and Turkey. The delegates included James Kelman, Booker Prize winner from Scotland and Turkish writers including Yaşar Kemal, Orhan Pamuk and others.

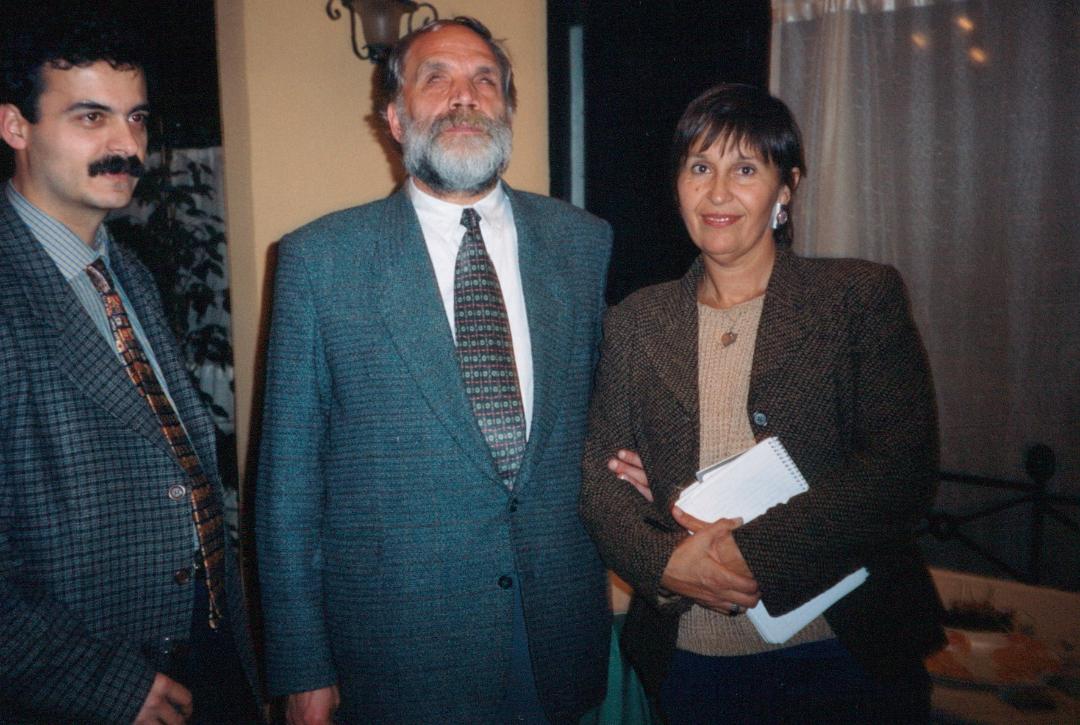

PEN members from 12 countries join Turkish colleagues for dinner at the first Gathering of the Initiative for Freedom of Expression in Istanbul, March 1997

On Monday we started the day at the State Security Court where Şanar petitioned the prosecutor for an appointment to question one delegate who had to leave early. Because the prosecutor didn’t want to bring charges against “international editors”, an act that would bring international attention, the “Turkish editors” could use this failure as further evidence of the unfair nature and application of the law when they took the case to the World Court. We approached the State Security Court again on Wednesday, when the prosecutor actually locked the gates and wouldn’t see any representative of our group. In the end nine of us—from USA, England, Scotland, Finland, Holland, Sweden, Canada (Quebec), Mexico and Russia—signed a form which said, “I accepted to be one of the collective publishers of this book willingly and I am aware of the legal responsibility. I have nothing else to say.” These forms were then sent registered mail to the prosecutor.

Two small groups visited prisons and the prisoners of conscience, including Dr. İsmail Beşikçi and his publisher Ünsal Öztürk in Bursa and journalist Işık Yurtçu in Adapazarı prison. Louise Gareau-Des Bois from Quebec PEN went to the Adapazari prison and was able to visit with Işık Yurtçu.

Kalevi Haikara from Finland and I went with Şanar on the ferry to the prison in Bursa where we met Ünsal Öztürk’s wife Süreyya. We waited and waited and talked together in the bleak courtyard with grey concrete walls rising around us topped with barbed wire, with guard towers looming over us. We went to the pink concrete building of Bursa Prison with a shield on the door “Ministry of Justice Bursa Special Prison” and waited there too. But we were not allowed to see İsmail Beşikçi, the noted Turkish sociologist and philosopher who wrote about the Kurds history and living conditions. He was one of the few non-Kurdish writers in Turkey speaking out about the treatment of the Kurds. At the time he was also one of the longest serving prisoners. He’d been sentenced to over 100 years though he was released from jail two years after our visit. Of his 36 books, 32 were banned in Turkey.

Kalevi Haikara from Finish PEN and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, WiPC Chair and member American PEN outside prison in Bursa, along with Süreyya, wife of prisoner Ünsal Öztürk (middle picture) and in conversation at Bursa Prison (far right picture.)

We were also not allowed to see Ünsal Öztürk, Beşikçi’s publisher, who had completed more than a three-year sentence. We met with the press which had gathered. We paid the outstanding fine against Öztürk with funds raised from Turkish writers, artists and many of the visiting PEN members. Öztürk was released the following day though there remained 30 outstanding cases against him, 62 charges waiting to be brought to court, all relating to Beşikçi. Every time he published a book, a charge was brought, but he kept publishing. Öztürk and his wife joined the conference.

The following day we attended the Justice House hearing of the “Kafka Trial.” When one editor of the Freedom of Expression book—actor Mahir Günşiray—faced the judges, he’d read a paragraph from Kafka’s The Trial. The paragraph offended the judges, and they brought a civil suit against him. Sixty-five other writers and artists signed on and said they also endorsed the reading of Kafka and should thus be guilty too. We all piled into the small room where the defendant Mahir Günşiray and his lawyer and the judge met. The hearing was the second or third for him, but with the room full of observers, the judge again postponed the proceedings.

At hearing of “Kafka Trial” in the Justice House

Many of us went next to Istanbul University to participate in a Forum on Freedom of Expression. However when we arrived, hundreds of students were protesting in the plaza, surrounded by riot police with shields. The situation was tense. In Ankara students had recently been arrested after they’d unfurled a banner in Parliament challenging the 300% tuition increase at state universities. The student protesters there were tried with the demand of 18-year prison sentences. The students at Istanbul University asked if we would speak at the rally. None of us were prepared for this potentially explosive scene. The writers who’d come to speak on freedom of expression asked me to talk for the group, all except Sascha from Russian PEN who also wanted to speak. Sascha, Şanar and I addressed the crowd. I emphasized that we were there to uphold the right for free expression, not to take a side with any particular party of government or to take sides on how education was financed in Turkey, but to insist that individuals should have the right to discuss, debate and write about these issues without facing prison terms. We urged that the protest stay nonviolent. We were then ushered out through the police corridor.

Rally at Istanbul University (Includes Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN), James Kelman (Scottish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Kalevi Haikara (Finish PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, (WiPC Chair/American PEN), Hanan Awwad (Palestinian PEN), Turkish writer Vedat Türkali, and Şanar Yurdatapan (with bullhorn).

In the evening the Istanbul Bar Association hosted us. The head of the Bar noted that the Turkish Constitution protects the state against the individual rather than the other way around as in the US. Everyone agreed there was free expression in many quarters of Turkey, but that the danger arose when one addressed Kurdish issues and Kurdish separatism and referred to the PKK.

Attending the meeting was the former PEN main case Eşber Yağmurdereli, a blind poet/dramatist, who’d served 14 years in prison. Released August 1991, he’d spoken in September 1991 at a meeting on behalf of Kurdish prisoners and had new charges brought against him. After five years he was still awaiting the resolution of that case. His passport had been taken from him. He could be sent back to prison for more than 20 years. He said he was unable to write, and if he wrote, he had to hide the writing and not publish. He earned his living now as a lawyer.

Meeting with Istanbul Bar Association. Eşber Yağmurdereli (middle) and Soledad Santiago (San Miguel Allende PEN) on right.

I also met the young brother of Bülent Balta, an investigation case. Balta, a chemistry honors graduate, a Turk, not a Kurd, had agreed to edit Özgür Gündem, the Kurdish newspaper, because of his sympathies for the difficulty of the Kurds. He had no particular experience as an editor, and after only 11 days was arrested and was serving a four-year prison sentence.

That evening the protest at Istanbul University was all over the news, including pictures of me with a bull horn speaking, but my words had been translated into Turkish so I had no clear idea what it was reported I was saying.

Early the next morning I slipped out of our hotel and walked to a large international hotel nearby where I called home. I asked my husband to confirm my return flight the following day. He asked what the flight was, but I told him to check with the travel agent and confirm. Over the phone I didn’t want to give flight details. I told him what was happening, including the widespread coverage of the protest with my participation, and he told me a colleague in Washington said that the American Embassy knew I was there and warned me not to leave the hotel. I had to leave the hotel, I explained. I was leading the delegation and events were planned, including a farewell dinner on the Bosphorus.

At the final panel/press conference, I noted that I had two sons, and as I observed the young people here, especially the young police officers and the young students, I felt sorrow that these youth were set across battle lines from each other. There was so much talent and promise we had seen. For the first time in the three days of speeches and press conferences, emotion stirred in my voice and I paused for a moment. One of the headlines the following day read something to the effect: “She Cries for Turkey!”

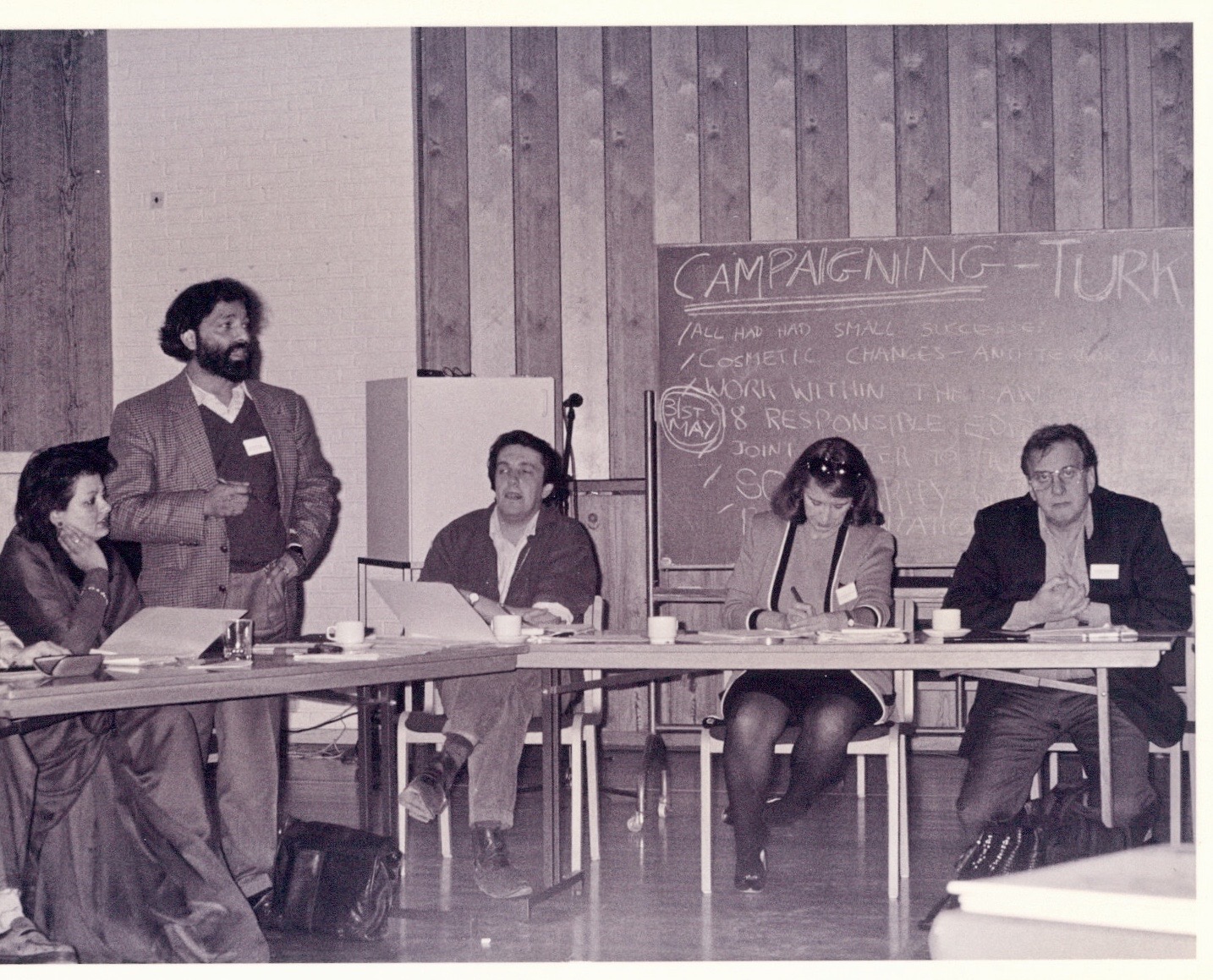

Panel at Initiative for Freedom of Expression Conference, Istanbul March, 1997

The following morning I was to be driven to the airport, but the driver didn’t show up, and I was left to find my own transportation in a taxi. The atmosphere around the conference had slowly made each of us cautious, even slightly paranoid. As I climbed into the taxi, driven by a stranger, I remembered the fortune teller on the ferry a few days before. Proceed with caution…was that her warning? You will make friends…was that the prediction? The road ahead is fortuitous but also fraught? In fact, I no longer remembered what her fortunes were, and I didn’t believe in fortunes or scattered coffee grounds, but I left Istanbul with a strong belief in the people and a commitment to the country and to the writers and publishers and lawyers and journalists and to the young people I had met and to the promise they represented.

In years following I returned to Turkey on numerous missions for PEN and for meetings with Human Rights Watch, with the International Crisis Group, on a trip with UNHCR looking at the Syrian refugee crisis, and several trips with my oldest son who wrestled in the World Championships and European Championships in Ankara and in the World Championships again in Istanbul and also lectured in mathematics at Koc University and other universities and with my youngest son who lived in Istanbul for two years with his two young children and wrote as a journalist on the Turkish/Syrian border and has set two of his four published novels in Turkey.

PEN International Writers in Prison Committee Centre to Centre newsletter special Turkey section April 1997

Next Installment: PEN Journey 20: Edinburgh—PEN on the Move, Changes Ahead

PEN Journey 18: Picasso Club and Other Transitions in Guadalajara

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

PEN perches on a three-legged stool. One leg is literature—the work of writers around the world. The other leg is freedom of expression—the defense of writers, particularly those in authoritarian regimes. The third leg is community—the fellowship among writers from over 100 countries sharing, appreciating, translating. PEN began as a loose network of clubs after World War I and grew quickly. The governance of the organization has evolved and at times set the three legs of the stool at odd angles to each other. One such occasion was at the Guadalajara Congress in 1996 as PEN celebrated its 75th anniversary.

My file for that Congress, whose theme was “Literature and Democracy,” bulges with documents and papers and programs in duplicates and triplicates. I don’t know why it is so much larger than the other files. In retrospect, the 1996 Congress was an inflection point, a turn in the road. Maybe I was collecting evidence.

Program from PEN International 63rd Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico

At the Congress I was handing over the reins of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), having finished my term, at least that was my intent. Ronald Harwood was doing the same as President of PEN International, at least that was his intent. Elizabeth Paterson was retiring after 28 years as Administrative Secretary of PEN, and WiPC researcher Mandy Garner was also moving on. PEN was navigating transitions, some planned, but others with a momentum of their own.

For the global context of that time, I reported as Chair of WiPC to the Congress:

“…two political phenomena have emerged, both perhaps linked to the end of the Cold War. First, we have seen conflicts erupting not so much between nations as within nations. This phenomenon, though not new, has offered particular challenges for the writer. Dozens of writers have been killed in conflicts in Algeria, Bosnia, Rwanda, Chechnya. In a number of counties with internal conflicts, including Peru, India, and Turkey, governments have used Anti-Terror Laws to arrest writers who write about the opposing parties.

“Another phenomenon is the increasing number of countries turning to the democratic process for government. The end of the Cold War saw the fall of many totalitarian regimes. Since 1990 over 50 countries have, at least on paper, turned to democracy to select their governments. However, democracy has not always settled so easily into place. One of the indispensable elements of a working democracy is freedom of expression, and this freedom has often been curtailed. Because PEN’s mandate is to protect the free flow of ideas and the freedom of writers to write, to criticize and to protest, PEN’s mission is as compelling today with newly emerging democracies as it was during the Cold War era. In country after country—from Albania, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Cote d’Ivoire, Croatia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Romania, Tajikistan, Zambia—writers can be and have been arrested on such charges as “disseminating false propaganda,” “insulting the President,” and “publishing false news.” The Writers in Prison Committee’s protests and work for these writers is fundamental in a larger political process that is unfolding…

“…Whenever one might feel despair for the way human beings can treat one another, the despair can be lifted by noting the caring of the writers who work for each other. The members of the new Ghana PEN have adopted a writer in Peru; Mexican members and Swedish members work for Turkish writers; Polish, Slovak, Nepalese, French and many other members work on behalf of imprisoned Vietnamese writers. Canadian writers are working on behalf of their Nigerian colleagues, an American writer writes in Portuguese to an Indonesian imprisoned writer; English and German writers have been in long-term correspondence with an imprisoned writer in South Korea. Danish writers are working for an imprisoned writer in Yemen; Norwegian, Finish, Austrian and Czech writers are protesting on behalf of Chinese writers; Australian and Catalan writers work for imprisoned colleagues in Myanmar/Burma…”

These corridors of concern linked men and women around the world in defense of each other and of freedom of expression. The Writers in Prison Committee was a place everyone came together to focus on PEN’s mission. Discussion on resolutions and actions began there and were taken to the full Assembly of Delegates.

That year resolutions passed and action was taken on cases in: Algeria where seven writers had been killed and many more threatened and arrested; the Dominican Republic where intolerance was growing and a writer had disappeared; Turkey where 50 writers were imprisoned and 100 others sentenced to prison; Indonesia where writers had been arrested and imprisoned and the famed writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer was under town-arrest and where in East Timor writers had been killed and leader and poet Alexandre (Xanana Gusmao) was in prison and sentenced to death; Iran where writers were disappeared, tortured and imprisoned; Central Asian Republics, particularly Tajikistan, where at least 29 journalists had been murdered in the last four years; China where dozens of writers were serving long prison sentences or were sentenced to re-education camps; Cuba where journalists were imprisoned and harassed; Mexico where journalists were killed, disappeared and threatened; Vietnam where writers were serving lengthy prison terms; and Nigeria where Ken Saro Wiwa had been hanged the year before and other writers were in prison.

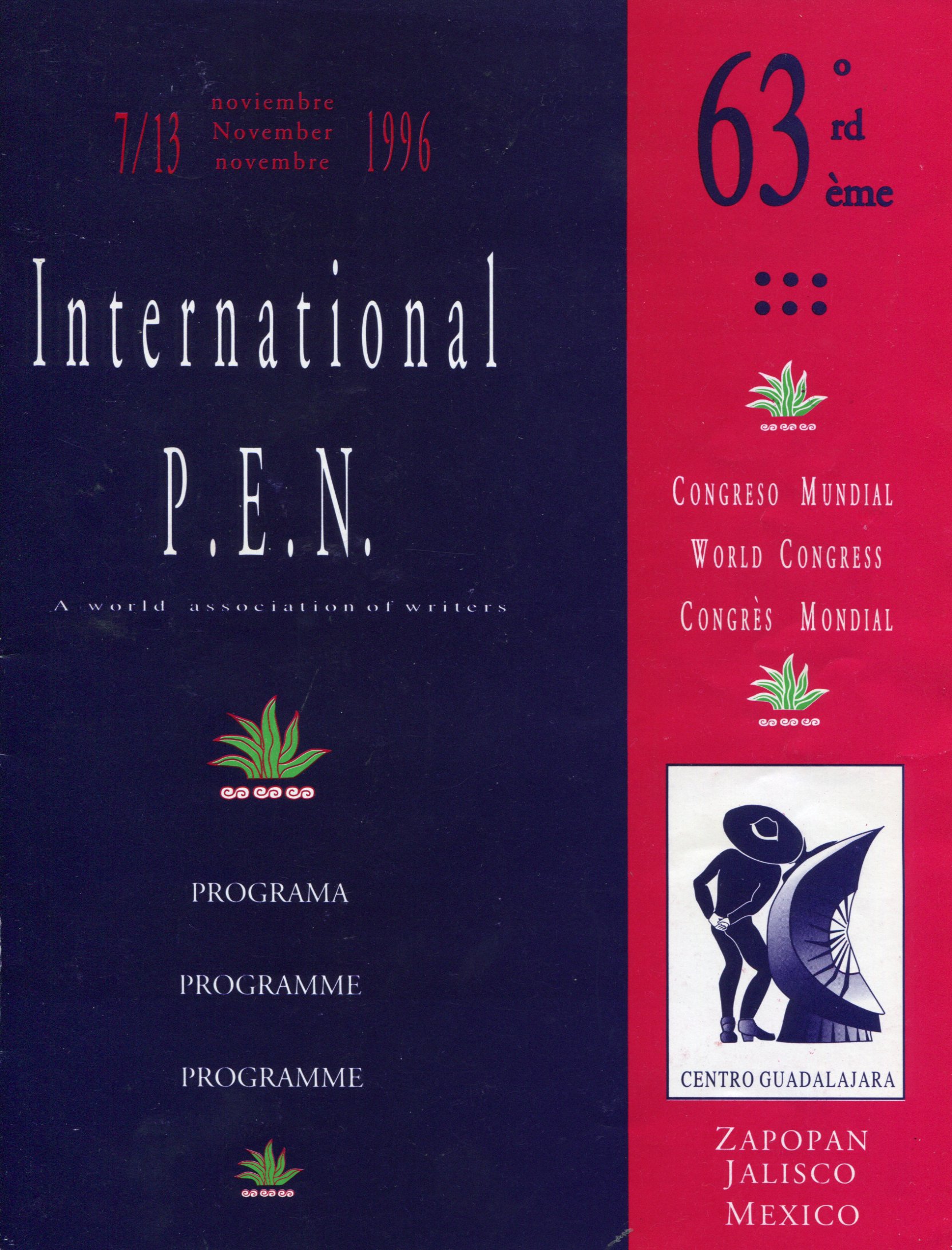

Writers in Prison Committee at Guadalajara Congress, 1996. L to R: Alexander Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (WiPC Chair), Mandy Garner (WiPC researcher)

At the WiPC meeting there was a report on PEN’s quiet mission to Cuba where writers were hoping the system would open up after the global changes in 1989. Writers there said they were in a goldfish bowl but never sure how big the bowl was from day to day, and those arrested often faced a choice between long prison sentences and exile. The WiPC meeting also heard from the sister of Myrna Mack, a Guatemalan anthropologist who had been killed and was one of the significant leaders of the worldwide movement against impunity. We also launched the anthology This Prison Where I Live of writings from PEN cases over the years.

In addition to the Writers in Prison Committee, the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, the Peace Committee and the Women’s Committee met in the early days of the Guadalajara Congress. Literary sessions focused on the Congress theme with programs on Literature of Old and New Democracies and Post-Communist Democracies.

Picasso Club neckties: Top l to r: Michael Scammel (International PEN Vice President), Carles Torner (Catalan PEN), Isidor Consul (Chair PEN Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee)

Also during those first days of the Congress, a group of members were meeting off site to launch a process to reshape the governance of PEN. For as long as anyone could remember, the International Secretary and President had been the sole decision-makers between Congresses where the Assembly of Delegates voted on issues. Many felt this system no longer allowed sufficient democratic expression for a worldwide organization.

I was friends with many of those meeting, but the WiPC staff and I kept out of the off-site gatherings. We felt we needed to keep the WiPC a neutral place where everyone came together. One morning the men in that group entered the Assembly of Delegates all wearing the same Picasso print necktie, “a figure twisted like a pretzel,” one member described later, ties bought at the Picasso restaurant where they had met. The group had felt shut out of discussions, and now were coming forward together. It was like a declaration of revolution. “For heaven sakes, take off the ties!” I recall someone saying, and the ties gradually were folded into pockets, but a revolution had begun.

Two Spontaneous Resolutions were introduced to the Assembly:

Spontaneous Resolution 1 On PEN’s Structure Submitted by the Swedish Centre, seconded by the Canadian Centre, and supported by the American, Bangladeshi, Catalan, Danish, Finnish, Japanese, Kenyan, Melbourne, Nepalese, Norwegian, San Miguel de Allende, Slovakian, Swiss German and USA West Centers.

Resolutions II on P.E.N’s Structure, submitted by the same centres.

“Taking into consideration the debate on P.E.N.’s composition, development and structure, held in Guadalajara on Sunday, November 10th, 1996, on the occasion of P.E.N.’s 75th anniversary;

Convinced of the need to enhance its democratic structure and facilitate wider international participation;

Resolves to request one P.E.N. Centre to elaborate the draft of a revised version of the current regulations, in cooperation and consultation with all the other Centres, as well as the International President and Secretary….”

After discussion and debate, it was agreed that PEN centers should send their suggestions for reform of the Constitution to the Japanese Centre, and Japanese PEN would coordinate and forward them to the International Headquarters and to all Centres so that the Centres could consider and vote on them at the 1997 Edinburgh Congress. One of these proposals, which was presented in Guadalajara by the Spanish-speaking Centres, was that Spanish should be made the third official language of PEN if financing could be raised.

Delegates at Writers in Prison Committee meeting PEN 63rd Congress in Guadalajara, 1996

PEN had its own democratic elections on the Congress agenda with a vote for the new International President. There was only one candidate put forward by the International Secretary and his PEN Center, a respected poet from Romania, a woman, who would have been the first woman President of PEN. She herself had lived under a repressive regime, but she had not been very involved in the international organization, and she had not been part of the discussion to reform PEN’s governance. When she spoke to the issue, questioning the need and the process, there was in the lunch conversations and in the corridors afterwards, pushback and a questioning of her suitability as President.

The next morning she withdrew her candidature. She said that it had become clear that the organization was undergoing a transformation and she felt she was the wrong person to be president at such a time of change. It seemed to her that PEN was in process of being transformed from an organization of writers into something less. She had been motivated by her dream of PEN, not as an organization with bureaucratic structures and competing pressure groups, but as a place where the writers of the world came together. She was a writer from Eastern Europe who had had great problems under successive dictatorships. From this perspective she had had an image of PEN as something extraordinary. It was true that she had confused PEN with the Writers in Prison Committee, she said. It was PEN which had spoken out when she was forbidden to publish. The work of the Writers in Prison Committee remained very important to her. What troubled her was the discovery of pressure groups who appeared to be fighting for a power which in her eyes had no existence. The only power which writers possessed was the power of their books and the fear of those in power that the truth told in those books would outlive their tyrannies.

Many members applauded her withdrawal speech. It articulated the pressure and tension in the 75-year-old organization which lived on ideals but also had to increasingly function in the competitive world of nongovernmental organizations with budgets and boards and democratic processes, an organization that needed to calibrate, modernize and keep all its members engaged.

Ronald Harwood agreed to serve another year as President. The International Secretary was reelected. Some members noted quietly that regulations required he face election every year now because of his age.

My replacement as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee was unanimously elected. The former President of Danish PEN, Niels Barfoed was a respected writer and longtime PEN member, who as a young boy had circumvented the Nazis as a courier with banned literature from his older brother who was in the Resistance. The WiPC had chosen a nominating committee to assure qualified candidate(s) were nominated. I left Guadalajara satisfied that the new WiPC process had come up with such a well-qualified Chair. I commiserated with Ronnie, thanking him for taking on another term though it meant his own writing would be curtailed. I was elected as a Vice President of PEN International and left Guadalajara happy to be returning to my own work. However, a few months later Niels fell ill and resigned, and I too was back as Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee. Ronnie and I served a fourth year together.

At the end of the Congress, I went to the airport with Alexandre Blokh, the longtime International Secretary. It had been a difficult Congress for him. He questioned whether he had stayed on too long. At the Edinburgh Congress in 1997 new governance and regulations were proposed, and at the 1998 Congress in Helsinki Alex stepped down after 16 years. PEN International was on its way to having an international board and more democratic governance which presented its own challenges as the organization proceeded towards the 21st Century.

PEN International Writers in Prison Committee bimonthly newsletter, July and September, 1996

Next Installment: PEN Journey 19: Prison, Police and Courts in Turkey—Freedom of Expression Initiative

PEN Journey 17: Gathering in Helsingør

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

What I remember most about the gathering of colleagues from 28 countries—31 PEN centers—51 of us in all at the first Writers in Prison Committee conference in 1996 was the seriousness of purpose and intellect during the day and the fun and talent in the evenings.

Hosted by Danish PEN, writers from every continent gathered at a university in Helsingør—known in English as Elsinore, the home of Shakespeare’s Hamlet—where we met in workshops and ensemble during the day to shape and refine our work on behalf of writers and freedom of expression around the world. But in the evening we were at a small university in a small city without transportation or distraction so we entertained ourselves. Each delegate displayed talents—from poetry reading to song to dance to musical performances.

As Chair of the WiPC gathering, I’d brought none of my own writing to read and was left to exhibit meager other talent which consisted of playing a few opening bars of Für Elise on the piano and whistling tunes with my far more talented Danish and Russian colleagues. Archana Singh Karki from Nepal in flowing red dress entertained with her graceful dance; Siobhan Dowd, our Irish former WiPC director and Freedom of Expression director at American PEN, silenced us with her soulful Irish folk songs, sung acapella; Sascha, Russian PEN’s General Secretary, not only whistled robustly but recited his poetry, which I was told I should be glad I didn’t understand with its bawdy content; Sam Mbure from Kenya and Turkish/English novelist Moris Farhi also read and recited work. PEN International President Ronald Harwood joined the discussions in the day and was audience in the evening. I don’t recall if Ronnie offered his own work, but we all bonded in our mission and in our support for the talent in the room.

Entertainment in the evening: From the top left—Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Chair of WiPC)in a whistling song; Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East) accompanying Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN) in dance; Siobhan Dowd (at piano—English & American PEN) with Moris Farhi (reading—English PEN); Sam Mbure (reciting—Kenyan PEN); Niels Barfoed (reading—Danish PEN)

During the three days, we fine-tuned our methods of working on and campaigning for our main cases, those writers who were imprisoned, attacked or threatened because of their writing, often their nonviolent voice of protest against authoritarian regimes. We considered PEN’s decision-making on borderline cases such as those which included drug charges, advocacy of violence, pornography, hate speech, terrorism. These were not categories we normally took on as cases. We discussed when we might take up such a case or assign them to investigation or judicial concern. We laid the groundwork for more joint actions among centers and other organizations such as the U.N., OSCE and IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.