Posts Tagged ‘Liu Xiaobo’

Hope: A Threshold of History

My wedding anniversary is June 3, but ever since the events at Tiananmen Square June 4, 1989, I merge the dates in my mind. I’m not sure why, but this year included, I made quiet dinner plans for our anniversary on June 4 by mistake. The Tiananmen memory for those who work on human rights does not recede. It isn’t visceral because I wasn’t there, but many of us watched first with hopeful attention the gathering of students and others in Beijing that spring and then in horror as the tanks rolled in.

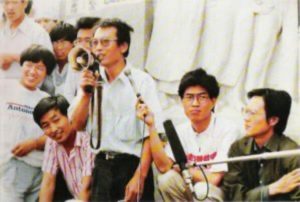

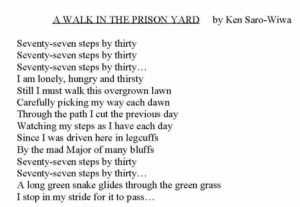

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

Though the Tiananmen Square protests and the names of participants like Liu Xiaobo have been struck from the internet in China and not recorded in history books for mainland Chinese students, the courage of the demonstrators and the repression of the government remain as historical facts and as memory.

Unfortunately, the memory is amplified today like a solemn tolling bell, repeating a mournful sound in places like Belarus, Venezuela, Iran, and Myanmar, where citizens push against authoritarian forces with nonviolent resistance. That bell, however, also echoes a higher enduring strain of freedom sought and won over the decades by citizens in Eastern Europe, South Africa, Chile and other countries, citizens who ultimately prevailed.

Those outside the direct struggles can remember and can support those in the resistance. For many of my colleagues, the support is through the work of PEN which campaigns for writers on the front lines. Often it is writers who are early victims since they are articulating an alternate vision to the authoritarian regime and are reporting the facts. Others open space for those who must leave their countries or lose their freedom or their lives and must work from the outside, organizations like the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) which finds alternate locations for writers and artists.

In the last few months, I’ve taken this space of a monthly blog to return to posts from years past. I’ve taken a core sample as a slice of my history during that month. I do so again here and note several posts: June 2008: Back on the River, June 2009: A Time of Hopening and June 2017: Storm Cloud on a Summer’s Day. Hope is a fragile but essential tool, one that holds history together so that it doesn’t shatter on the shoals, on the disappointments and misbehaviors of humankind.

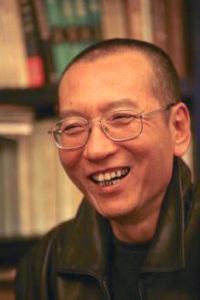

Liu Xiaobo was China’s first citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010, but he was in prison in China as “an enemy of the state.” Liu Xiaobo died in custody July 2017.

As I celebrate my wedding anniversary with my husband of many decades this June 3/4, I do so with the hope offered by Liu Xiaobo to his friends and fellow citizens whom he believed in when he noted in his “Final Statement:”

“I have no enemies and no hatred…Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy…

“For there is no force that can put an end to the human quest for freedom, and China will in the end become a nation ruled by law, where human rights reign supreme…

“Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth. To strangle freedom of speech is to trample on human rights, stifle humanity, and suppress truth.”

Since April I’ve been back on the Potomac River, sculling in the rushing waters after the spring rains, dodging logs and flotsam flowing downstream from Great Falls and beyond. I’ve been pressing into the middle of the river on hot, sultry days in June when barely a breeze stirs the air, though the current still hurries beneath the boat. I’ve been rowing beside much larger sculls from the universities, dodging the wake of the speed boats which cruise along beside the Viking-size crafts as coaches shout instructions. In my small white scull I’ve tried to hear what they call and emulate the grace and power of the collegiate oarsmen and women.

Facing forward, watching the landscape recede as I move backwards, I’ve been thinking about the past even as I plunge into the future. This perspective of the rower, driving headlong towards what he can’t see except for quick glimpses over his shoulder, is a useful one to master.I’m back in Los Angeles this week for readings and interviews and will be talking about my own earlier fiction—No Marble Angels and The Dark Path to the River. Many of the short stories in No Marble Angels are set during the Civil Rights era—the Nashville sit-ins, the Little Rock school integration, the aftermath of the ’68 riots in the cities. It was a time when ordinary citizens took extraordinary actions. It’s easy to romanticize the times, but the consequence of many of those actions changed our laws and our lives and opened up our society. The future grew out of the clarity of purpose of those who could glance over their shoulders and press towards the future even as they had to face the restrictions of their present day.

As the U.S. moves into its next era—whatever that may eventually be called—one hopes it will be a period of national and international Rights Realized.

As a young mother, I used to tell stories to my two sons constantly—on the way to school, standing in long lines anywhere, on car, plane or bike rides, on hikes. I would ask each to give me two things (people, ideas, places, plots) they would like in the story, and then I would weave the disparate ingredients into a tale. Their elements might include something like a dog, a butterfly, a battle of some sort, and a waterfall…the possibilities were open and endless, though usually there was some battle involved and some animal in most of the stories.

Over the last year and a half, partly urged by my now adult sons, I’ve committed to writing a blog post once a month. For me the process is a bit similar to the earlier exercise as I look over the month and try to wrap ideas, thoughts, events into 600 words. This month’s elements are particularly rich, probably too rich for a 600-word essay, though the literary form of the blog hasn’t been established or defined so it can, I suppose, be whatever one wants.

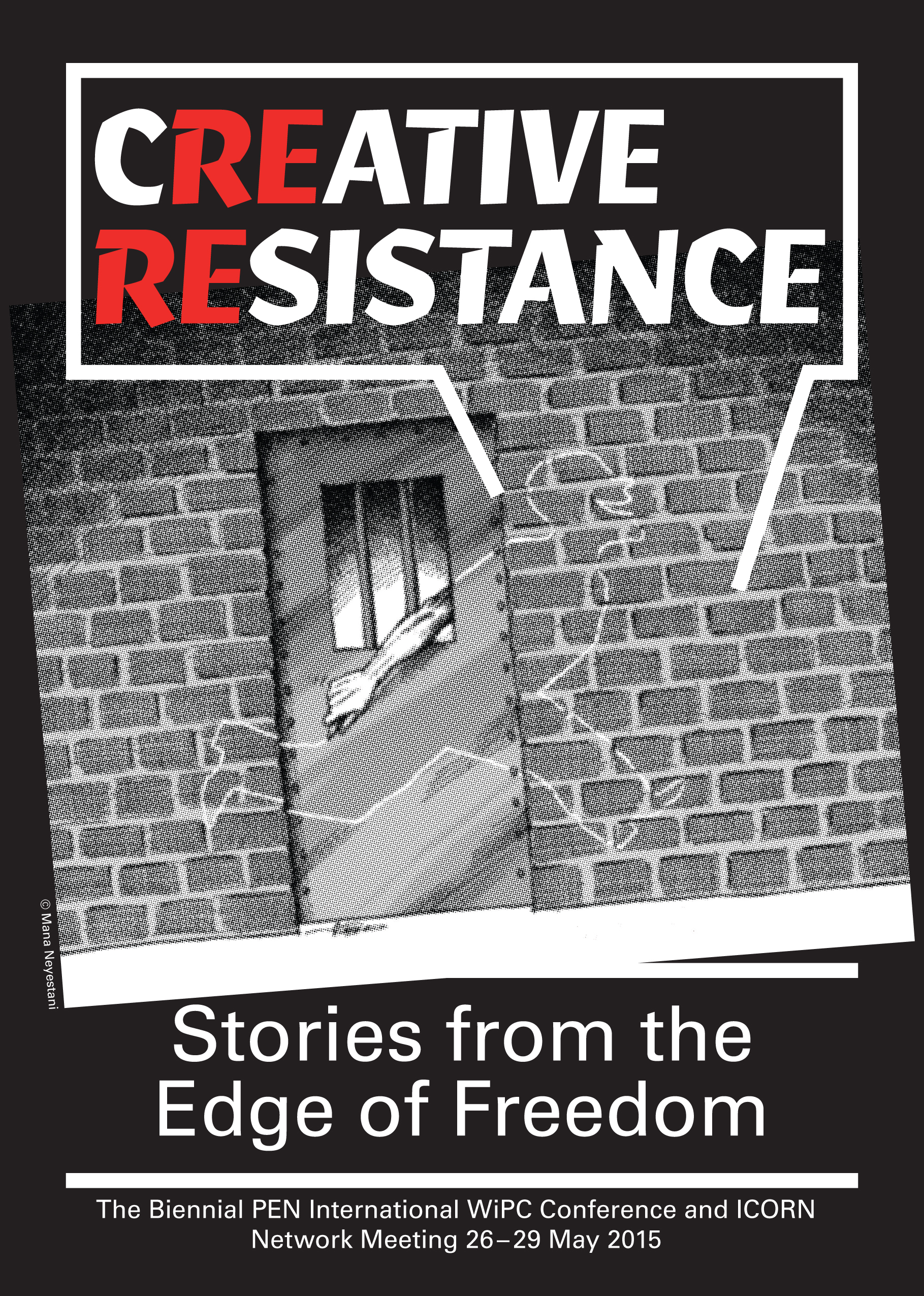

I began June at an International PEN Writers in Prison conference joined to the Global Forum on Freedom of Expression conference in Oslo, Norway, where the sun doesn’t set in the summer. In Oslo, activists from organizations around the globe discussed, debated, and strategized into the summer nights about the state of freedom of expression around the world and the mechanisms to protect it. Everyone understood that societies without this freedom are most often without political and civil freedoms as well so the defense of freedom of expression is the front line.

The timing of the conference coincided with the 20th anniversary of the crackdown in Tiananmen Square in China. This year of 2009 is also the 20th anniversary of the popular uprising against the military government in Burma/Myanmar after the election of Aung San Sui Kyi, who was re-arrested this May; it is the 20th anniversary of the fatwa in Iran against Salman Rushdie after the publication of The Satanic Verses, and it is the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The year 1989 was a threshold year. So where have we come twenty years later?

After Oslo, I went briefly to Paris en route to Normandy, where the 65th anniversary of the World War II invasion was being celebrated. I was headed to Normandy for a bike trip through the countryside and the historical sites, not for the official celebrations, but I was in Paris the day President Obama and his family arrived. It was also the day of the men’s semi-finals of the French Open in tennis. (You see the elements of this blog complicating…)

Driving back to the hotel after Federer beat Del Potro and Soderling beat Gonzalez, I was talking in my broken French with the taxi driver talking in his broken English about the matches and about the arrival of Obama and about world politics in general. The driver was ebullient—an oxymoron perhaps for a French taxi driver—but he was ebullient nonetheless.

“The world…the U.S…France…Europe…it is hopening,” he said, gesturing with his arms, trying to explain what he meant about the opening he saw in the world and the hope he felt. “We have hopening between us!”…[cont]

June 2010: Summer Reading: Under a Tree With a Book

Summer has come with hot, steamy breath in Washington this year—already days nearing 100°. Even with the sudden flash of thunderstorms, the air clears only to steam up again. So much for my assurance to a newcomer that summer wasn’t so bad here, though maybe we will pay our dues in June and be rewarded with the summer breezes and cool evenings in July. August, we know, will be hot.

In the dog days it is a time to be indoors, or at least in the shade—biking along the Potomac or sculling on the river only early in the morning or as the sun is setting. Indoors or under the shade of a tree, it is a time to read.

Summer reading—the term brings back delicious childhood memories even of hot Texas summers where I would find a patch of shade in the back yard and lose myself in a book, or bike to a nearby pool and sit reading between laps, or curl up in a chair under the fan on the screened porch. I can still smell the mowed grass and the sweet fragrance of white gardenias on the bushes just outside.…[cont]

June 2011: Mockingbirds at Fort McHenry: A Tribute to Elliot Coleman

(The excerpt below is from a larger article about the poet and teacher Elliott Coleman in the recent Fortnightly Review:)

I was 20 years old, applying to Johns Hopkins graduate Writing Seminars from a small Midwestern college. I had come to campus to meet Elliott Coleman, the director and founder of the program. He had read my application and invited me to lunch at the Faculty Club. Looking back now and understanding the processes of application and the competition for a position in the Writing Seminars, I realize how remarkable his attention was, but he showed that kind of attention to students, making each feel important and valued.

I had sought out his work before I came to Baltimore. I no longer remember how I found the slim volumes of poetry in my remote college town before online ordering, but I did, and I had read his book of poems Mockingbirds at Fort McHenry. When I spoke about those poems, he was genuinely humbled and surprised that I had made the effort to read his books.

He asked, “Would you like to go see Fort McHenry?” That afternoon, the student showing me around drove us all out to Fort McHenry, and I walked around the area with Elliott Coleman as he talked about poetry and the genesis of his poems. I’m sorry I didn’t write down what he said, or if I did, I can no longer find the notes of that afternoon. But I knew then that Hopkins was where I wanted to be if I had the chance, and even though I was a fiction writer, I wanted to study with Elliott Coleman. Fortunately, I got that opportunity.

Elliott Coleman radiated a gentleness, a caring and a humility that shed light, illumining those around him. He didn’t seek the center of attention; he didn’t draw the spotlight to himself, rather he shined so that light fell on others.

From Mockingbirds at Fort McHenry:

Through a window in Tunis the green searolls its light. A few square white houses dazzle the Atlas mountains, the color of lions and honey. This foothill is hardly Africa; this bay is hardly Mediterranean. They partake of each other by reflection, absorbed as they are in the depths of space.

I recently engaged with facebook (no, I didn’t buy stock), but I gave in. I concluded that I needed at least to understand (is that possible?) and experience the social media phenomena and at most learn from and enjoy the connection to friends and colleagues, most of whom I know, but some of whom I just read and some of whom read me.

For the last three months I’ve checked my “wall” every few days and scroll through hundreds of shared observations, photos, and comments. The process is surprisingly quick. I engage more like a magazine editor with an unexamined metric for judgment, pausing to “like” certain contributions, commenting on a few and sharing even fewer on my own personal and authors’ facebook pages.

For the present at least I’ve limited my fb world and page largely to literature and human rights in order to put some boundary on the possibilities and on that evaporating commodity of privacy–not a 21st century value and an oxymoron in a discussion of facebook. That is not to say I don’t enjoy the news and photos and commentary on a range of issues from all the friends, but in my fb space, this is my focus for now.…[cont]

June 2013: No blog posted

June 2014: No blog posted

June, 2015: What Are You Not Reading This Summer?

I was recently sent a questionnaire as part of a profile asking me what I was reading:

I find myself reading several books at the same time. I just finished Phil Klay’s Redeployment today, am reading Jennifer Clement’s Prayers for the Stolen, am re-reading Graham Greene’s The Comedians, re-reading Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this and can’t leave this question without noting Elliot Ackerman’s Green On Blue. Because I read both e-books and paper books, I move around among narratives easily.

The answer was a snapshot in reading time, indicative of the pleasure of dancing among narratives. I find myself enjoying on several platforms the movement  between hard-edged, nuanced stories of war and its aftereffects in Klay’s Redeployment and Ackerman’s Green on Blue, the harsh and surprising world of Clement’s indigenous Mexican women in Prayers for the Stolen and the gentle, but no less desperate stories of Southern women trying to find their lives in Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this, a collection recently re-published by a new small press—Bacon Press—in paperback. Graham Greene is a master who I am always re-reading, appreciating how he integrates the international world of politics and deceit with compelling narratives set around the world.

between hard-edged, nuanced stories of war and its aftereffects in Klay’s Redeployment and Ackerman’s Green on Blue, the harsh and surprising world of Clement’s indigenous Mexican women in Prayers for the Stolen and the gentle, but no less desperate stories of Southern women trying to find their lives in Kate Blackwell’s you won’t remember this, a collection recently re-published by a new small press—Bacon Press—in paperback. Graham Greene is a master who I am always re-reading, appreciating how he integrates the international world of politics and deceit with compelling narratives set around the world.

Recently I returned from PEN International’s biennial Writers in Prison conference and the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) meeting, a gathering this year in Amsterdam focused on Creative Resistance, a gathering of over 250 individuals from 60 countries around the world who work on behalf of writers threatened, imprisoned and killed for their writing. I remain conscious of these voices too. They occupy a kind of negative space—those we are NOT reading, not able to read because they are not able to write.

The list unfortunately is long, and many individuals stand out for me, but I will highlight two here. Though I couldn’t read either because of language differences, I read with attention their cases and link here to actions that can be taken on their behalf:…[cont]

June 2016: No blog posted.

June 2017: Storm Cloud on a Summer’s Day

It is an almost perfect summer day—the sun is shining in a white cloud sky; the air is warm, not yet sweltering. Light filters through white umbrellas shading diners at the outside restaurant by the park. On this almost perfect New York day I am thinking about the rulers in China who have imprisoned for the last nine years one of the country’s courageous thinkers for ideas that will outlast him and his jailers.

Today it was announced Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo is in critical condition, on medical parole having been given a terminal diagnosis. As a principal author of Charter’08 which advocates for nonviolent democratic reform in China, Liu Xiaobo, writer, critic and activist has lived his life as a man of ideas.

As the sun shifts above me, skirting over skyscrapers, finding a gap between the umbrellas and spreading over my table, I consider the trajectory and the life of an idea as it dawns, unfolds, iterates, then flies off where it is embraced, where it empowers and takes on a life of its own. Ideas are connected to, but not owned or encumbered by, those who articulate them.

The fallacy—the fundamental fallacy—of the rulers in China and elsewhere lies here. No one can imprison ideas. No one can manage or own the imagination of another. Government leaders can physically restrain with the hope that the idea will die, but in the case of Liu Xiaobo, the ideas behind Charter ’08, which was signed by more than 2000 Chinese citizens from all walks of life, endure. These ideas calling for a freer society continue to grow wings, often quietly, but sometimes even more quickly as the physical confines grow harsh.

“Any man or institution that tries to rob me of my dignity will lose,” declared Nelson Mandela. It is an injunction worth noting.

June 2018: No blog posted.

June 2019: [Beginning in May, 2019 I started writing a retrospective of work with PEN International for its Centenary so posts were more frequent in 2019-2020. In June 2019 there are two posts in the PEN Journeys and in June 2020 there are four.]

June 2019: PEN Journey 3: Walls About to Fall

Our delegation of two from PEN USA West—myself and Digby Diehl, the former president of the Center and former book editor of the Los Angeles Times—arrived in Maastricht, The Netherlands in May 1989 for the 53rd PEN International Congress. We joined delegates from 52 other centers of PEN around the world, including PEN America with its new President, fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Meredith Tax, founder of what would soon be PEN America’s Women’s Committee and later PEN International’s Women’s Committee. Meredith and I had met at the New York Congress in 1986 where the only picture of the Congress on the front page of The New York Times showed Meredith and me in the background at a table taking down the women’s statement in answer to Norman Mailer’s assertion that there were not more women on the panels because they wanted “writers and intellectuals.” Betty Friedan argued in the foreground.

Front page of the New York Times, 1986. Foreground: left – Karen Kennerly, Executive Director of American PEN Center, right – Betty Friedan, Background: (L to R) Starry Krueger, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Meredith Tax.

Over the previous months the two American centers of PEN had operated in concert, mounting protests against the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and bringing to this Congress joint resolutions supporting writers in Czechoslovakia and Vietnam.

The theme of the Maastricht Congress—The End of Ideologies—in large part focused on the stirrings in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as the region poised for change no one yet entirely understood. A few weeks earlier, the Hungarian government had ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire fence along the Hungary-Austrian border be turned off. A week before the Congress, border guards began removing sections of the barrier, allowing Hungarian citizens to travel more easily into Austria. In the next months Hungarian citizens would rush through this opening to the West.

At PEN’s Congress delegates from Austria and Hungary sat a few rows apart, separated only by the alphabet among delegates from nine other Eastern bloc countries which had PEN Centers, including East Germany. This was my third Congress, and I was quickly understanding that PEN mirrored global politics where writers were on the front lines of ideas and frequently the first attacked or restricted. Writers also articulated ideas that could bring societies together.…[cont]

June 2019: PEN Journey 4: Freedom on the Move: East to West

I have attended 32 International PEN Congresses as president of a PEN Center, often as a delegate, as Chair of the International Writers in Prison Committee, as International Secretary and now as Vice President. The number surprises me when I count. The Congresses have been held on every continent except Antarctica. Many were grand affairs where heads of State such as Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, Angela Merkel in Germany, Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal greeted PEN members. Some were modest as the improvised Congress in London in 2001 when PEN had to postpone the Congress planned in Macedonia because of war in the Balkans. PEN held its Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia the following year. At these Congresses writers from PEN centers all over the globe attended. Today PEN International has centers in over 100 countries.

Among the more memorable and grand was the 54th PEN Congress in Canada, held in September 1989 when PEN still held two Congresses a year. The Canadian Congress, staged in both Toronto and Montreal by the two Canadian PEN centers, moved delegates and participants between cities on a train. The theme—The Writer: Freedom and Power—signaled hope at a time when freedom was expanding in the world with writers wielding the megaphone.…[cont]

54th PEN Congress in Canada, 1989. Front row: WiPC chair Thomas von Vegesack, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman and PEN USA West Executive Director Richard Bray. Back row: Digby Diehl (right) and other delegates.

June 2020: PEN Journey 30: Barcelona: A Surprise

I was having lunch with my husband at a Georgetown restaurant in Washington, DC on a Saturday in May, 2004. I was due to fly out the next day for Barcelona to attend International PEN Writers in Prison Committee’s 5th biennial conference, part of a larger Cultural Forum Barcelona 2004. My husband and I were talking about our sons—the oldest was getting a PhD in mathematics and was also training for the 2004 Olympics as a wrestler, hoping to make the British team. (He had dual citizenship.) The younger, recently graduated with an advanced degree in International Relations, had just deployed to Iraq as a Marine 2nd Lieutenant and was heading into a region where the war was over but the insurgency had begun. It was an intense time for our family, yet as parents there was not much we could do except to be there, cheering for our oldest at his competitions and writing letters and sending packages and prayers for our youngest. It was a time when as parents we realized our children had grown beyond us and were taking the world on their own terms.

I was planning to be away for the week in Barcelona where PEN members from around the world were gathering for the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) and Exile Network meetings. Carles Torner, PEN International board member, chair of PEN’s Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee and former President of Catalan PEN, had helped arrange International PEN’s participation and funding as part of the Universal Forum of Cultures—Barcelona 2004. This would be the largest WiPC conference to date with delegates from every continent and multiple speakers and side events.

Carles, a poet, fluent in PEN’s three official languages English, French and Spanish, was one of the highly respected, organized and talented PEN members. He’d also been involved in the years’ long reformation of PEN International. As members looked to who could be a strong replacement for the current International Secretary when Terry Carlbom’s term ended in a few months, there was widespread enthusiasm for Carles to stand for the office. I was among the enthusiasts.

My phone rang at that Saturday lunch. International PEN Board member Eric Lax, already in Barcelona for meetings, said he had news and a question; he told me he was calling on behalf of others as well. The news: the Catalan government had also recognized Carles’ talents and had offered him a position as Director of Literature and Humanities Division at Institut Ramon Llull to promote Catalan literature abroad. A father of three, Carles had accepted this paid position which meant he couldn’t stand for PEN International Secretary, an unpaid position. He wouldn’t have the time for both, and there would be conflicts of interest.

Eric asked if I would allow myself to be nominated. A number of members and centers, including the two American centers, were asking, he said. PEN’s Congress where the election would take place was only a few months away in September and nominations were due soon. I was flattered but said no for a number of reasons. Eric asked that I not answer yet, just come to Barcelona, talk with people and let them talk with me.…[cont]

June 2020: PEN Journey 31: Tromsø, Norway: Northern Lights

The week before PEN’s 70th World Congress in Tromsø, Norway in the Arctic Circle, my oldest son competed in the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, the only wrestler to qualify for TeamGB (Great Britain). He had dual citizenship and was the first British champion to qualify for the Olympics in wrestling in eight years. In his sport, there was no seeding of competitors; instead, after making weight, each wrestler reached into the equivalence of a hat and drew their first round competitions. True to his history, my son drew the best opponents. As one news commentator noted: “Coming to the mat is Nate Ackerman, born in the US, wrestling for Great Britain, getting his PhD in mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology…but that won’t help him now as he faces the three-time World Champion from Armenia.” My son lost to the Armenian wrestler. His other opponent was the world bronze medalist from Kazakhstan who went on to win the silver medal at the Olympics. Though my son didn’t win either match, he also didn’t get pinned, and he wrestled nobly. The Olympic Games in Athens was a magical time.

Olympic circles projected in light on the Acropolis at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens

I was heading to Tromsø with a smile inside, though behind my smile was also a quiet attention that never left me for my youngest son, a Marine, was in Anbar Province, Iraq that summer, patrolling in 120° and alert for IED’s and snipers along the roadside. He had missed his brother in the Olympics and his brother missed being able to talk with him.

As I changed planes in northern Europe, I realized I was going to need a coat in the Arctic Circle and bought a light foldable one at an airport shop which I took to a decade worth of PEN Congresses after. On the plane I reviewed the stack of PEN papers and resolutions.

I was arriving at the Congress having agreed to stand for International Secretary. (See PEN Journey 30). The other PEN member standing was Giorgio Silfer, a poet and playwright and president of Esperanto PEN.

Norwegian PEN hosted over 300 writers, editors, and translators from at least 60 countries for the 70thWorld Congress whose theme was Writers in Exile—Writers in Minority Languages. The Rica Arctic Hotel where we stayed and met was an easy walk to the small downtown of Tromsø, capital of northern Norway, well above the Arctic Circle and called “the Paris of the North.”…[cont]

June 2020: PEN Journey 32: London Headquarters: Coming to Grips

PEN is a work in progress. It has always been a work in progress during its 100 years. Governing an organization with centers and members spread across the globe in over 100 countries can be like changing clothes, writing a novel and balancing a complex checkbook all while hang gliding. Perhaps an exaggeration, but not by much.

In 2004 the leadership of President and International Secretary were at the center of the governing structure along with the Treasurer and a relatively new Board. The President represented PEN in international forums. The International Secretary was tasked with overseeing the office and the centers of PEN and with any tasks the President handed over like running board meetings and setting up the agenda for work. The concept was that PEN should be able to elect as President a writer of international stature to represent PEN in global forums but not have the obligation to run the organization. That could be the role of the International Secretary, along with the Board and staff.

When I assumed the role of International Secretary, PEN did not yet have an executive director, though the consensus had built from the strategic planning process that we needed one. Both the President and International Secretary were volunteer, unpaid positions, which meant they were not full time. At the post-Congress board meeting after Tromsø, we agreed to begin a search for an executive director.

International PEN President Jiří Gruša

I suggested monthly board meetings, which had not been the practice. We could do these by phone, which meant there were only a few hours a day when everyone would be awake. If Judith Rodriguez in Melbourne, Australia could stay up past 11pm and Eric Lax in Los Angeles didn’t mind waking up at 7am, the rest of us—Takeaki Hori in Japan, Sibila Petlevski in Croatia, Eugene Schoulgin in Norway, Elisabeth Nordgren in Finland, Cecilia Balcazar in Colombia as well as President Jiří Gruša when he joined from Vienna or Prague and me in Washington, DC or London—could find our time zone and call in. The technology was not as sophisticated as today, and we didn’t yet use skype so the calls were not cheap, but we began to manage each month.…[cont]

June 2020: PEN Journey 33: Senegal and Jamaica: PEN’s Reach to Old and New Centers

A few days before I flew out to Dakar, Senegal for a PEN conference in November 2004, my youngest son, a Marine in Iraq, called and told my husband and me that we would not hear from him for a while. We knew, without being told, that the U.S. and British troops were likely about to return to Fallujah, the center of the insurgency. Civilians there had been advised to get out of the city, and they were leaving.

On the opening day of the PEN conference in Dakar, November 7, 2004, the battle for Fallujah began. The headlines in the newspapers in Dakar were about the civil war raging in neighboring Ivory Coast so I was not reading about Iraq during the five-day PEN Africa meeting. In 2004 there were no iPhones or phone news feeds and rare coverage of the Middle East was on the evening news. I was quietly attentive each day and prayerful and focused on PEN’s work.

I have modest notes from the first PAN Africa conference, but I have some of my most vivid memories, most particularly of the people I met and of my first trip to Gorée Island just off the Senegalese coast opposite Dakar, a place of its own historic upheaval. Gorée Island was the site of the largest slave-trading center on the African coast from the 15th to the 19th century, ruled successively by the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French. The dungeons and portals to the sea where men and women and children were sent out in chains still stood along with the stucco houses of former slave traders.

Gorée Island, site of slave trading in 15-19th centuries, off coast of Dakar, Senegal

A tall Gambian doctoral student assisting Senegalese PEN guided a few of us around Gorée. Fluent in French, English and Spanish, he was writing a doctoral thesis on the secrets of history and myth in the epic of Kaabu according to Mandingo oral traditions—clearly a future PEN member. Thoughtful, knowledgeable, he spent the day sharing history. During and after the Dakar meetings, our paths crossed in subsequent PEN conferences and congresses, and we know each other still. Dr. Mamadou Tangara earned his doctorate at the University of Limoges in France shortly after and eventually became the Gambian Permanent Representative to the United Nations. During Gambia’s constitutional crisis in 2016-17, he and other diplomats called for the president to step down peacefully; he was dismissed, but when power changed hands a few months later, he was reappointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Gambia. The friendship with Mamadou Tangara remains and is one of my many valued friendships from PEN.

Mamadou Tangara (Gambia) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary) on Gorée Island at PEN’s 2004 Dakar conference

Mamadou’s mentor at the time was an older Gambian journalist and editor Deyda Hydara, who joined PEN members from more than a dozen African centers in this conference to prepare for PEN’s first PAN African World Congress in Senegal in 2007. The Congress would be PEN’s first in Africa since the 1967 Congress in the Ivory Coast when American playwright Arthur Miller was International PEN President. Though the Gambia didn’t yet have a PEN Center, Deyda was planning on starting one. At the time Deyda Hydara was co-founder and primary editor of The Point, a major independent Gambian newspaper. He was also correspondent for AFP News Agency and Reporters Without Borders and was an advocate for press freedom and a critic of his government’s hostility to the media.

A month after PEN’s Dakar conference, the Gambian government passed a bill allowing prison terms for defamation and another bill requiring newspaper owners to purchase expensive operating licenses and register their homes as security. Deyda Hydara announced his intent to challenge these laws. Two days later on December 16, 2004 Deyda Hydara was assassinated on his way home from work. To this day his murder remains unsolved. The following year Deyda Hydara won PEN America’s Freedom to Write Award posthumously and later the Hero of African Journalism Award of the African Editors Forum.…[cont]

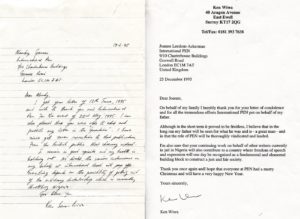

Nobel Peace Prize for Liu Xiaobo Ten Years After

PEN International marks the ten-year anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to writer, literary critic and human rights activist Liu Xiaobo on 10 December 2010. PEN’s Liu Xiaobo Anniversary Campaign acts as a commemoration of Liu Xiaobo’s life, his contribution to Chinese literature, and his selfless work promoting basic freedoms in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The campaign also highlights the cases of writers Gui Minhai, Kunchok Tsephel, Yang Hengjun and Qin Yongmin who are currently detained by the PRC government. The campaign seeks to raises awareness of their situation, to boost advocacy work on their behalf and to ensure that they and their families feel supported and not forgotten.

The following links to PEN’s campaign. Below is text and Chinese translation of my video tribute to Liu:

Hello, I’m Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, Vice President Emeritus of PEN International.

您好!我是乔安尼•利多姆-阿克曼,国际笔会荣休副会长。

Ten years ago, essayist, poet, activist and PEN member Liu Xiaobo was the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Peace. Liu envisioned and worked towards a peaceful and democratic pathway for China. Beginning with the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and through the subsequent decades, he spoke out and wrote and gathered people and ideas in support of a China where individual freedom was valued and protected.

十年前,散文家、诗人、活动家、笔会成员刘晓波成为首位荣获诺贝尔和平奖的中国公民。刘先生设想并致力于中国走向和平民主的道路。他从1989年天安门广场抗议运动开始,在随后数十年言说和书写,并聚集民众及理念,以支持一个重视和保护个人自由的中国。

In 2008, he and others drafted Charter 08, which set out this democratic vision. He and others gathered hundreds and then thousands of signatures from Chinese citizens who endorsed the vision. Charter 08 did not call for an overthrow of the government so much as a transformation of the way government related to its citizens in a transition to a democratic society that would include freedom of expression and assembly.

2008年,他和其他人起草了《 零八宪章》,阐明这一民主愿景。他们从支持这一愿景的中国公民那里汇集了成百上千人签名。 《零八宪章》并未呼吁推翻政府,而是要转变政府相对于公民的方式,转型为包括言论自由和集会自由的民主社会。

Liu Xiaobo has been called the Nelson Mandela or Václav Havel of China because of his ideas, his activism and his leadership. Like Havel, Liu was committed to nonviolent action as a means of achieving change, and he was an inspired writer.

刘晓波因其理念、言行和领导能力而被称为中国的曼德拉或哈维尔。像哈维尔一样,刘晓波也致力于以非暴力行动来实现变革,他是一位受鼓舞的作家。

Liu Xiaobo (with megaphone) at the 1989 protests on Tiananmen Square.

I first encountered Liu Xiaobo through PEN. After the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989, PEN worked on behalf of the writers who had been arrested in the protest, including Liu Xiaobo. Liu had also been instrumental in persuading students to leave the Square before the soldiers and tanks rolled in to attack and possibly kill them. At the time of Tiananmen Square, I was President of PEN Center USA West. A few years later when Liu was again imprisoned for his writing, I was Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee.

我首先通过笔会遭遇刘晓波。在1989年天安门广场镇压后,笔会致力于代表在抗议活动中被捕的作家,包括刘晓波。刘晓波还曾劝说学生离开广场,以免士兵和坦克席卷攻入广场可能杀死他们。在天安门广场抗议时,我担任美国西部笔会会会长。几年后,当刘晓波再次因写作而被监禁时,我是国际笔会狱中作家委员会主席。

Liu Xiaobo then went on to become one of the founders and the second President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), whose members lived inside and outside of China. He was instrumental in establishing the platforms by which these writers could communicate and share ideas about a society where freedom of expression and democratic processes could exist.

刘晓波随后成为独立中文笔会(ICPC)的创始人之一和第二任会长,该笔会成员居住在中国境内和海外。他发挥作用建立起这个平台,这些作家们可以借此平台,交流和分享有关这样一个社会的理念,在那里言论自由和民主进程得以存在。

During the time Liu was President of ICPC, I was the International Secretary of PEN. However, Liu was not allowed out of mainland China into Hong Kong where ICPC had its meetings, and I didn’t get to the mainland until in 2010 after he was arrested for the fourth and final time, so we never met in person, though over decades I have worked with many of his colleagues.

在刘晓波担任独立中文笔会会长期间,我曾担任国际笔会秘书长。然而,他没获准离开中国大陆前往独立中文笔会举行会议的香港,而直到他 第四次也是最后一次被捕后的2010年,我才去中国大陆,因此我们从未亲身见面,尽管数十年来我一直与他的许多同事共同工作。

Liu Xiaobo was the writer the Chinese government feared the most and therefore arrested. Liu was charged as “an enemy of the state” for “incitement of subverting state power” because of his ideas, his writing and his participation in the drafting and circulating of Charter 08. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison. He was the only recipient of the Nobel Prize who was in prison at the time and not allowed to attend the ceremony. Only an empty chair represented him. His wife Liu Xia was also not allowed to attend. Liu Xiaobo died in custody July 13, 2017.

刘晓波是中国政府最害怕的作家,因此而被捕。由于其理念、写作并参与起草和传播《 零八宪章》,刘晓波被指控为“煽动颠覆国家政权”的“国家敌人”。他被判处了十一年徒刑。他是当时在监狱中而未被允许参加颁奖典礼的唯一诺贝尔奖得主,只有一把空椅子代表他。他的妻子刘霞也被禁止出席。刘晓波于2017年7月13日去世。

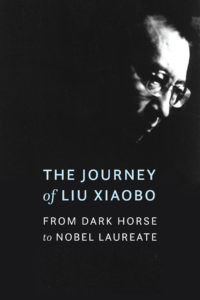

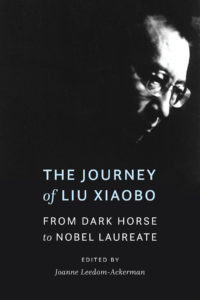

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

After his death, writers around the world who knew him began to write about him, his work, about China and the path of liberalism and democratic aspirations. This year THE JOURNEY OF LIU XIAOBO: FROM DARK HORSE TO NOBEL LAUREATE was published containing more than 75 of these essays—probably the largest gathering of writing from China’s democracy activists—and is both a memoir and tribute to Liu Xiaobo and a study of China’s Democracy Movement.

他去世后,全世界了解他的作家开始书写他及其作品,书写中国以及自由主义和民主理想之路。今年出版了《刘晓波之旅程:从黑马到诺奖得主》(文文版),包含75篇以上的文章,可能是来自中国民主活动人士的最大笔墨聚会,既是对刘晓波的回忆致敬,也是对中国民主运动的研究。

China’s Democracy Movement and Liu Xiaobo’s legacy still inspire those inside and outside of China, from the mainland to Xinjiang to Tibet to Hong Kong and to neighboring countries engaged in the struggle for political reform and an end to authoritarian rule.

中国民主运动和刘晓波的遗产,仍然激励着中国内外的人们,从大陆到新疆,到西藏,再到香港,再到争取政治改革和结束专制统治的邻国。

Some have said that because of China’s ascendency in the last decade, the legacy of Liu Xiaobo has been reduced to nothing. But a longer view of history shows that the same was said of those visionaries and martyrs for free societies in Eastern Europe and South Africa.

有人说,由于近十年来的中国崛起,刘晓波的遗产被削减为零。然而,更长的历史证明,同样的说法也曾针对过那些在东欧和南非争取自由社会的远见者和烈士们。

Societies move forward and are changed by ideas, by leaders, and ultimately by their citizens. Liu Xiaobo did not aspire to personal power, but those in power came to fear him because he understood how to move ideas into action.

社会向前发展,并通过理念、领导者及最终通过其公民而改变。刘晓波并不渴望个人权力,但是当权者却开始害怕他,正因为他知道如何将理念付诸行动。

As individuals one by one—be they writers, lawyers, academics or others—are put into prison and taken out of the discourse, those in power attempt to maintain their control. That is why it is important to keep an eye not only on the monolith of regimes and government, but to protect the individuals who hold the powerful to account.

当作家、律师、学者或其他人一个接一个地被关进监狱并从话语中带走时,当权者试图维持其控制。这就是为什么重要的不仅是着眼于政权的垄断和政府问题,而且要保护那些向当权者追责的个人。

Liu Xiaobo declared, “Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth.”

刘晓波声言:“表达自由,人权之基,人性之本,真理之母。”

Liu Xiaobo insisted that to transition to a state that one wanted to live in, one needed to have citizens who represented those values even in the struggle.

刘晓波坚持认为,要过渡到一个人们想要生活的国度,就需要有即使在斗争中也代表那些价值观的公民。

I’d like to read from his Final Statement to the judge who sentenced him: “…now I have been once again shoved into the dock by the enemy mentality of the regime. But I still want to say to this regime, which is depriving me of my freedom, that I stand by the convictions…I have no enemies and no hatred…Hatred can rot away at a person’s intelligence and conscience. Enemy mentality will poison the spirit of a nation, incite cruel mortal struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and hinder a nation’s progress toward freedom and democracy. That is why I hope to be able to transcend my personal experiences as I look upon our nation’s development and social change, to counter the regime’s hostility with utmost goodwill and to dispel hatred with love.”

我要朗读他的《我的最后陈述》,是他写给判决他的法官的:“……现在又再次被政权的敌人意识推上了被告席,但我仍然要对这个剥夺我自由的政权说,我坚守着……信念——我没有敌人,也没有仇恨。……仇恨会腐蚀一个人的智慧和良知,敌人意识将毒化一个民族的精神,煽动起你死我活的残酷斗争,毁掉一个社会的宽容和人性,阻碍一个国家走向自由民主的进程。所以,我希望自己能够超越个人的遭遇来看待国家的发展和社会的变化,以最大的善意对待政权的敌意,以爱化解恨。”

After Liu Xiaobo’s death, a colleague who had known and worked with him for decades was asked if he thought Xiaobo would have changed his statement had he known his end. His friend said No, that his final statement and sentiment that “I have no enemies, no hatred” was at the heart of who Liu Xiaobo was.

刘晓波去世后,一位与他认识并合作了数十年的同道被问到,如果刘晓波知道自己的结局,他是否认为晓波会改变自己的陈述。他的朋友说“不会”,因为“我没有敌人,也没有仇恨”的最后陈述和观点,正是刘晓波其人的核心。

Now Liu Xiaobo’s beloved wife Liu Xia, who is herself a poet, will read one of his poems written to her: “Van Gogh and You” addressed to “Little Xia”:

现在,刘晓波的挚爱妻子,自己也是诗人的刘霞,将朗诵他写给她的一首诗:《梵高与你——给小霞》:

PEN JOURNEY: Introduction—Raising the Curtain: The Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and was asked by PEN International to write down memories. I have done so in 46 PEN Journeys and have been asked to write an introduction to these. Below is the introduction coming last, drawn in part from an earlier blog post of the same title, but not in this PEN Journey sequence.

“In a world where independent voices are increasingly stifled, PEN is not a luxury. It is a necessity.”—Novelist & poet Margaret Atwood, former President of PEN Canada

“…freedom of speech is no mere abstraction. Writers and journalists, who insist upon this freedom, and see in it the world’s best weapon against tyranny and corruption, know also that it is a freedom which must constantly be defended, or it will be lost.”—Novelist Salman Rushdie, PEN member

PEN International was started modestly 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catharine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others, conceived if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, they reasoned, at least among writers of Europe.

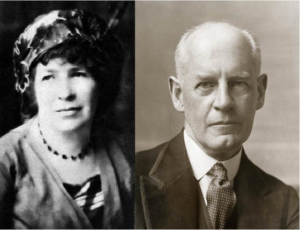

PEN Founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and first PEN President John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN [Poets, Essayists & Novelists—later expanding to Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Editors and Novelists and now including a wide array of Nonfiction writers and Journalists] spread quickly. Clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, and the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. A decade later when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he donated the prize money to International PEN. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace. Galsworthy spoke about the possibilities of a “League of Nations for Men and Women of Letters.”

Members of PEN began to gather at least once a year in 1923 with 11 Centers attending the first meeting. During the 1920’s writers regardless of nationality, culture, language or political opinion came together. As the political temperature rose in Europe, PEN insisted it was an apolitical organization though its role in the politics of nations was soon to be tested and ultimately landed not on a partisan or ideological platform but on a platform of ideals and principles.

At a tumultuous gathering at PEN’s 4th Congress in Berlin in 1926, tensions rose among the assembled writers, and the debate flared over the political versus non-political nature of PEN. Young German writers, including Bertolt Brecht, told Galsworthy that the German PEN Club didn’t represent the true face of German literature and argued that PEN could not ignore politics. Ernst Toller, a Jewish-German playwright, insisted PEN must take a stand.

After the Congress Galsworthy returned to London and holed up in the drawing room of PEN’s founder Catharine Scott where he worked on a formal statement to “serve as a touchstone of PEN action.” This statement included what became the first three articles of the PEN Charter. At the 1927 PEN Congress in Brussels, the document was approved and remains part of PEN’s Charter today, including the idea that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.” The third article of the Charter notes that PEN members “should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people and dispel all hatreds and champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

As the voices of National Socialism rose in Germany, PEN’s determination to remain apolitical was challenged though the determination to defend freedom of expression united most members. At the 1932 Congress in Budapest the Assembly of Delegates sent an appeal to all governments concerning religious and political prisoners, and Galsworthy issued a five-point statement, a document that would evolve into the fourth article of PEN’s Charter.

When Galsworthy died in January 1933, H.G. Wells took over as International PEN President. It was a time in which the Nazi Party in Germany was burning in bonfires thousands of books they deemed “impure” and hostile to their ideology. At PEN’s 1933 Congress in Dubrovnik, H.G. Wells and the PEN Assembly launched a campaign against the burning of books by the Nazis and voted to reaffirm the Galsworthy resolution. German PEN, which had failed to protest the book burnings, attended the Congress and tried to keep Ernst Toller, a Jew, from speaking. Some members supported German PEN, but the overwhelming majority reaffirmed the principles they had just voted on the previous day. The German delegation walked out of the Congress and out of PEN and didn’t return until after World War II. Their membership was rescinded. “If German PEN has been reconstructed in accordance with nationalistic ideas, it must be expelled,” the PEN statement read. During World War II PEN continued to defend the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. (Today German PEN is one of PEN’s active centers, especially on issues of freedom of expression and assistance to exiled writers.)

PEN was one of the first nongovernmental organizations and the first human rights organization in the 20th century. PEN’s Charter, which developed over two decades, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II. In 1949 PEN was granted consultative status at the United Nations as “representative of the writers of the world,” and is today the only literary organization with formal consultative status with UNESCO.

In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in more than 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries, defend linguistic rights and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia in the late 1980’s and in other countries of the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar where a former prisoner of conscience was instrumental in forming a center there and was its first President. A PEN center is a refuge for writers in many countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

For more than 35 years I have been engaged with PEN, as a member, as the President of one of PEN’s largest centers, PEN Center USA West during the year of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie and Tiananmen Square, as Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), as International Secretary (2004-2007), and continuing as an International Vice President since 1996. I’ve also served on the Board and as Vice President of PEN America (2008-2015). I lived for six years in London, where PEN International is headquartered.

In the run-up to PEN’s Centenary, I was asked if I would write an account of PEN’s history as I’d seen it. I began by posting a blog twice a month, taking on small slices of the history in each narrative. This serial blog of PEN Journeys recounts PEN’s history as I’ve witnessed it as well as history of the period and personal history during those years. The narratives are framed by the times, featuring writers, including the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the protests in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall—PEN members or future PEN members were central in all these events—the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of PEN Centers there; the opening up of Eastern Europe with its PEN centers; the release of PEN “main case” Václav Havel and his ascendency to the Presidency of Czechoslovakia; the mobilization of Turkish PEN members in opposition to recurring authoritarian governments; PEN’s mission to Cuba; PEN’s protests over killings and impunity in Mexico; protests and gatherings in Hong Kong on behalf of imprisoned Chinese writers; the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Peace to PEN member and Independent Chinese PEN Center founder and President Liu Xiaobo.

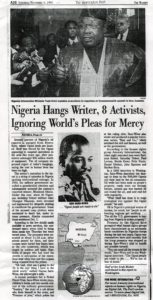

PEN and its members have played a pivotal role in defending freedom of expression around the world, in challenging systems that trap citizens, and in at least two instances, in taking on the presidencies of the new democracies that emerged. The PEN Charter, which sets out the principles and ideals, has united the global organization and guided its members who have often been at the forefront or in the wings of important historical moments—celebrated and outspoken writers like Václav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk, Yaşar Kemal, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Koigi wa Wamwere, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Arthur Miller, Anna Politkovskaya, Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Carlos Fuentes, Liu Xiaobo. The list is long, and I have had the privilege of interacting with many of them in PEN and also with hundreds of perhaps lesser known, but courageous writers who have stood watch and engaged.

The view of PEN Journey is global though the work is often local. As well as chronicling global events and personal history, PEN Journey recounts the shaping and re-imagining of this sprawling nongovernmental organization, one of the largest in terms of geographic reach. PEN has had to evolve and re-shape itself to serve its 155 autonomous centers. With at least 40,000 members around the globe in more than 100 countries, there are many stories others might tell, but this narrative is a close-up view of a period of time and of the writers who continue to work together in the belief that the world for all its differences and complexities can aspire to and perhaps even achieve “the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”* [*PEN Charter]

Because I tended not to throw away documents over the decades, I have an extensive paper as well as digital archive which I used to refresh memories and document facts. As I dug through files, I came across a speech I’d given which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman speaking at PEN International Conference on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

The talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is ongoing. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King is quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

From Diyarbakir Conference:

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through PEN’s 141 centers in 99 countries. [Now 155 centers in over 100 countries.] They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see for himself this ancient city, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together.

–Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International, March 2005

PEN Journey 43: Turkey and China—One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

January 2007 began with an assassination. The Board of PEN International was just gathering in Vienna for the first meeting of the year when board member Eugene Schoulgin got a phone call letting him know that our colleague and his friend Turkish-Armenian editor Hrant Dink, had been gunned down in Istanbul and killed. Many of us had seen Hrant at the PEN Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul in March.

Editor-in-chief of the bilingual Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, Dink had long advocated for reconciliation between Turks and Armenians and for Turkey’s recognition of the Armenian genocide early in the century. Dink had received death threats before and had himself been prosecuted for “denigrating Turkishness,” but as with Russian colleague Anna Politkovskaya, Dink’s assassination stunned us all and set off widespread protests in Turkey and abroad. Eventually a 17-year old Turkish nationalist was arrested and convicted, but not before police were exposed posing and smiling with the killer in front of a Turkish flag.

PEN International Board Meeting, Vienna, January 2007. L to R: Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary; Jiří Gruša, International President; Caroline McCormick, Executive Director; Judy Buckrich, Women Writers Committee Chair; Elizabeth Norgdren, Finish PEN; Eugene Schoulgin, Norwegian PEN; Franca Tiberto, Search Committee Chair; Sibila Petlevski, Croatian PEN; Britta Pedersen, International Treasurer; Eric Lax, PEN USA West; Mohamed Magani, Algerian PEN; Kata Kulavkova, Translation and Linguistic Rights Chair; Frank Geary, Programs; Karen Efford, Programs.

The work of PEN is, at its heart, personal. It is writers speaking up for and trying to protect other writers so that ideas can have the freedom to flow in society. In league with other human rights organizations, PEN also advocates to change systems that allow attacks and abuse. At times the work can feel ephemeral when the systems don’t change, or make progress only to regress. However, the individual writer abides, and PEN’s connection to the writer stands.

During my tenure working with PEN, Turkey and China have been the two countries that have imprisoned the most writers. For a period both nations appeared to be advancing towards more open societies but soon retreated. In the early 2000’s as Turkey aspired to join the European Union, the country operated as a democracy with a more independent judiciary; fewer writers became entangled in the judicial processes. However, in 2007 the democratic transition in Turkey began to veer off course and has continued a downward spiral towards authoritarianism ever since.

China also promised to become a more open society with the advent of the Olympic Games in 2008. Democracy activists inside and outside of China grew hopeful. In this climate, PEN held an Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in Hong Kong in February 2007; it was PEN’s first in a Chinese-speaking area of the globe. Over 130 writers from 15 countries gathered, including writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and many of PEN’s nine Chinese-oriented centers as well as members from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Nepal, Australia, the Philippines, Europe, and North America.

Both China’s and Turkey’s Constitutions protected freedom of expression in theory, but in practice the protection was lacking. Instead, laws and regulations prohibited content. In Turkey, exceptions included criticism of Ataturk, expressions that threatened “unitary, secular, democratic and republican nature of the state” which in effect targeted issues around Kurds and Kurdish rights. In China, the Constitution noted that “in exercising their freedoms and rights, citizens may not infringe upon the interests of the State, of society or of the collective, or upon the lawful freedom and rights of other citizens.” The state was the arbiter.

The Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 took place at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories with programs also at Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club. The theme Writers in the Chinese World celebrated Chinese literature and a dialogue among PEN’s Asian centers and also explored issues of translation, women, exile, peace, censorship, internet publishing, freedom of expression and PEN’s strategic plan.

Asia and Pacific Regional Conference in 2007 at Po Leung Kuk Pak Tam Chung Holiday Camp at Sai Kung, a scenic seaside area in the New Territories. Over 130 writers from 20 PEN centers in 15 countries gathered for the four-day conference.

However, 20 of the 35 mainland Chinese writers who planned to attend were prevented or warned off by government authorities, including the President of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) Liu Xiaobo, who later won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2010 while imprisoned in a Chinese jail. Qin Geng had his permit rescinded and two writers—Zan Aizong and Zhao Dagong—were stopped at the border and denied permission to exit though they had permits. (Two overseas Chinese writers who attended and had other citizenship—Gui Minhai and Yang Hengjun—are now in prison in China and are PEN main cases.)

In addition, the Chinese Communist government banned eight books, including one by Zhang Yihe, an honorary board member of the ICPC who had been invited to speak at the conference but instead was warned not to attend.

China’s promised opening of its society was already contracting, and the restrictions bore a harbinger of events to come both for writers and eventually for Hong Kong. The conference attracted wide press attention with articles in Chinese and English newspapers in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao and globally via the BBC and newswire services. Renowned Shanghai playwright Sha Yexin, poet Yu Kwang-chung (Yu Guangzhong) from Taiwan and Korean poet Ko Un, short-listed for the Nobel Prize for Literature, attended. But the restrictions on the mainland Chinese writers cast an ominous shadow and grabbed the largest regional and international headlines.

“PEN has nine centers representing writers in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and abroad and has great respect for Chinese Writers and Chinese literature,” International PEN President Jiří Gruša told more than 40 reporters at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, “but we are very concerned by the restrictions on writers in mainland China to write, travel and associate freely.”

In honor of the absent writers, an empty chair sat on the platform for each session of the four-day conference.

Press Conference at Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club, February 2007; L to R: Translator, Journalist Gao Yu (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Jiří Gruša (PEN International President), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary)

In 2007 more than 800 writers were under threat worldwide, and at least 33 writers were in prison in China. A number of the attendees at the conference had been imprisoned and been main cases for PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), including celebrated Korean poet Ko Un and Chinese journalist Gao Yu, both of whom addressed the conference. They knew firsthand the role of the writer in the struggle for freedom, and they knew the support PEN had given, observed one of the conference organizers Yu Zhang, General Secretary of the ICPC, half of whose members lived in mainland China.

“I am no longer afraid of anything,” one Chinese writer unable to attend said in a message to the conference. “Our bodies and our spirits are our own. To speak of ugliness and injustice we have to shout, but our throats are cut when we do.”

“We are willing for some things to be burned in the soil so a new leaf will come,” added another mainland writer in a message to the conference.

“It is important that all writers get together, and all writers protect the freedom of speech and free expression. We must write what’s in our hearts and write as a witness to history,” said Qi Jiazhen, who spent 10 years in a Chinese prison and now lived in exile.

Owen H.H. Wong of Hong Kong’s English-Speaking PEN Center pointed out that Hong Kong was a meeting point of East and West, North and South, Leftists and Rightists and Modernization and Classic writing. He noted that before the 1997 handover, Hong Kong writers saw themselves as writers in exile. Only those born in Hong Kong regarded themselves as Hong Kong writers. Now most publishing houses in Hong Kong were funded by the Communist government, and free expression in Hong Kong was threatened and controlled.

Yu Jie, a Beijing-based essayist and author and vice President of ICPC, spoke at the Foreign Correspondents Club noting that even though he was able to attend the conference and speak to the foreign media, he had not been able to get published in mainland China. For mainland writers, Hong Kong was a place where freedom of expression and freedom of the press still existed, he said. “It’s as if those of us in the mainland have our heads immersed in water and cannot breathe, but Hong Kong allows us to stick our heads above the surface of the water, and for a short time, breathe freely.”

He predicted that the authorities would later “settle the score” with the writers and publishing houses. He was in fact later arrested, tortured and imprisoned for his writing. In 2012 he emigrated to the United States.

PEN International Panel at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference. L to R: Conference organizers included Yu Zhang, (Independent Chinese PEN Center), Caroline McCormick (PEN International Executive Director), Chip Rolley (Sydney PEN)

“Existing in the unofficial nooks and crannies of an emerging civil society in China, ICPC is determined to insist that their country live up to the rights guaranteed in its Constitution,” said another conference organizer, Chip Rolley, Vice President of Sydney PEN. “This continuing work will ensure that there is indeed a turning point for PEN in China and the wider Asia and Pacific region, and that this historic conference will not dissipate like smoke.”

In his keynote address Taiwanese writer and poet Yu Kwang-chung called for “all the writers and the poets across the Chinese world” to strengthen the channels of mutual exchange, and make efforts to find a consensus on basic issues such as the formation of a common national culture (which includes in particular the establishment of joint aesthetic and literary values) in order to “make a valuable contribution to preventing war and maintaining peace.”

Attendees launched a dialogue on literature as well as on networking among PEN’s Asian centers with a regional strategy for freedom of expression and translation. The conference was part of PEN International’s program to develop the regions in which PEN operated by connecting existing writers and PEN centers and also developing new centers in countries starting to open up such as Myanmar/Burma. Often a PEN center was one of the first civil-society organization to set down roots when authoritarian controls began to relax. [A Myanmar PEN Center was established in 2013.]

In a panel on Literature and Social Responsibility panelists noted that free speech and writers’ responsibilities were the basis of social prosperity and that PEN was a bridge between writers and their responsibilities.

Participants at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, Nepal, including speaker Yu Kwang-chung (Taiwan) seated in center.

Chen Maiping of ICPC read a message from Zhang Yihe, the mainland novelist who was to have been on the panel but who had been prevented from attending. “There is a saying: human hearts are like water, while people’s favor and loyalty feel as heavy as mountains. During these ten plus days since my books were banned, so many people have shown their concern I have nothing to give in return for their kind support other than to express my gratitude on paper. Writing is my only means of self-expression. Writers have always been prisoners of language and words. It is not an easy affair for me to live, nor can I die in peace. I can only write…In China we talk about ‘literature as a vehicle for the Tao (the Nature, the Way).’ People have talked about this for thousands of years. However, those who have written the best literature are exactly those who never think about their social responsibility. Zhang Bojun [the author’s father who was a scholar and a minister in the Chinese government in the 1950s and persecuted during the 1957 Anti-Rightist campaign in Mao’s Cultural Revolution] was an example of this. In my view his achievements were much greater than many of the contemporary writers, artists and painters. If a writer has too strong a responsibility, he may have no achievements at all.

“For several decades, literature has been tied together with ‘revolution’ and ‘reform.’ I can’t bear such responsibility. I can only recall the past. I do not have such social responsibility tied to ‘revolution‘ and ‘reform.’ I am out of date. There are so many people singing praise for the society, why not allow an old woman like me to sing a little song of my own. I am only a piece of withered leaf. I hope that I can decay quickly so that I may become a new leaf soon. “

Chen Maiping also read “Writing in Anger” by Liu Shu, another mainland writer prevented from attending. “The conflicts between our hearts and reality and an unwillingness to keep silent are the driving forces for my writing. The disgraceful politics have turned us into dissident writers. Chinese dissident writers write in isolation. The marginalized position of dissident writers has marginalized their writing. This is very different from the West. The Eastern people have the ability to suffer and digest their sufferings. This kind of ability enables writers to ignore the reality and to become numb to the suffering of their people. They choose to write only about ‘pleasant things to lighten the load on their hearts.’

“The cruelty of reality fills their lives with ‘submission.’ The writers are swollen and weighed down with humiliations and sufferings; they have lost the anger created by their reality. They have no anger at the past, nor do they imagine a future. They only write about meaningless, shallow and trivial affairs. My anger comes from my refusal to accept and make peace with this reality. I have been detained four times because of my ideas. We puzzle over social phenomena but we long for peace. The way to calm our anger is to write…I must speak for citizens who were screened by the totalitarian society, by the police and the ugly society…we do not want to be silent. Like Lu Xun said, life is ourselves: everybody is responsible for his own life. Our flesh body and our life are in exile in our homeland, until we disappear.”

Women Writers Committee gathering at Asia and Pacific Regional Conference including Chair Judy Buckrich in turquoise in center.

Women participants at the conference focused in addition on the restrictions for women writers in the region.

Qi Jiazhen was imprisoned 10 years and accused of trying to overthrow the government after she inquired whether she could study aboard. She said she had been young and inexperienced and felt guilty and wrong, the same feeling shared by other women. Gender awareness was low in China, she said. She now lives in Melbourne, Australia.

Celebrated mainland journalist Gao Yu confirmed two kinds of prisoners in China—special treatment prisoners & prisoners of conscience. As vice chief editor of an economic weekly with an international reputation, she was a special treatment prisoner. She had treatment when she was sick and had to do little hard manual work because was already 50 and given 7 years in prison. But she never admitted her wrong doing so she didn’t enjoy any pain reductions, she said.

Chinese journalist and PEN main case Gao Yu with translator.

In a panel on Censorship and Self-Censorship, Gao Yu noted that censorship began at school where children learned to protest injustice when not treated fairly. Later in life that grew into resistance of the system. The writer who sought to express truth experienced censorship which could lead to punishment and prison. But that was not as frightening as being silent, she said. The essence of being a writer was to have integrity and speak the truth.

After the conference, a dozen police picked up one participant and took him to a hotel room to find out what the conference had been about. A poet and member of ICPC, he told the police, “To build a ‘harmonious society’ and ‘harmonious culture’ [as President Hu Jintao has called for], writers should sit with writers and not always have to sit with policemen.” He was finally released after hours of interrogation.

One of the more creative campaign tools planned during the conference was spearheaded by a team of PEN Centers in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. The members developed a digital relay with Chinese poet Shi Tao’s poem June. The poem tracked the path of the Olympic torch across a digital map. Shi Tao was serving a 10-year prison sentence for sharing with pro-democracy websites a government directive for Chinese media to downplay the 15th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests. His emails had been turned over to the Chinese government as evidence by Yahoo. His poem commemorated the Tiananmen Square massacre and was translated and read in the languages of PEN’s centers around the world, including in regional dialects as well as in the major languages. Ultimately 110 of PEN’s 145 centers participated and translated the poem into 100 languages, including Swahili, Igbo, Krio, Tsotsil, Mayan. The poem’s journey began on March 30, 2008 in Athens and traveled to every region on the online map, arriving in Hong Kong on May 2 and in June to Tibet where it was translated into Tibetan and the proposed Uyghur PEN center translated it into Uyghur. Finally August 6-8 it arrived in Beijing where it was translated and read in Mandarin. Anyone could click on the map and hear the poem in the language of the country designated.

By the 2008 Olympic Games 39 writers remained in prison in China.

June

By Shi Tao

My whole life

Will never get past ‘June’

June, when my heart died

When my poetry died

When my lover

Died in romance’s pool of blood

June, the scorching sun burns open my skin

Revealing the true nature of my wound