Posts Tagged ‘PEN Writers in Prison Committee’

PEN JOURNEY: Introduction—Raising the Curtain: The Arc of History Bending Toward Justice?

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and was asked by PEN International to write down memories. I have done so in 46 PEN Journeys and have been asked to write an introduction to these. Below is the introduction coming last, drawn in part from an earlier blog post of the same title, but not in this PEN Journey sequence.

“In a world where independent voices are increasingly stifled, PEN is not a luxury. It is a necessity.”—Novelist & poet Margaret Atwood, former President of PEN Canada

“…freedom of speech is no mere abstraction. Writers and journalists, who insist upon this freedom, and see in it the world’s best weapon against tyranny and corruption, know also that it is a freedom which must constantly be defended, or it will be lost.”—Novelist Salman Rushdie, PEN member

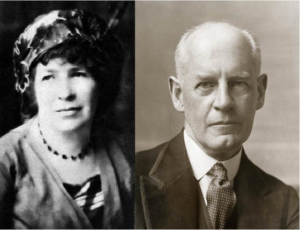

PEN International was started modestly 100 years ago in 1921 by English writer Catharine Amy Dawson Scott, who, along with fellow writer John Galsworthy and others, conceived if writers from different countries could meet and be welcomed by each other when traveling, a community of fellowship could develop. The time was after World War I. The ability of writers from different countries, languages and cultures to get to know each other had value and might even help reduce tensions and misperceptions, they reasoned, at least among writers of Europe.

PEN Founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott and first PEN President John Galsworthy

The idea of PEN [Poets, Essayists & Novelists—later expanding to Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Editors and Novelists and now including a wide array of Nonfiction writers and Journalists] spread quickly. Clubs developed in France and throughout Europe, and the following year in America, and then in Asia, Africa and South America. John Galsworthy, the popular British novelist, became the first President. A decade later when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he donated the prize money to International PEN. Not everyone had grand ambitions for the PEN Club, but writers recognized that ideas fueled wars but also were tools for peace. Galsworthy spoke about the possibilities of a “League of Nations for Men and Women of Letters.”

Members of PEN began to gather at least once a year in 1923 with 11 Centers attending the first meeting. During the 1920’s writers regardless of nationality, culture, language or political opinion came together. As the political temperature rose in Europe, PEN insisted it was an apolitical organization though its role in the politics of nations was soon to be tested and ultimately landed not on a partisan or ideological platform but on a platform of ideals and principles.

At a tumultuous gathering at PEN’s 4th Congress in Berlin in 1926, tensions rose among the assembled writers, and the debate flared over the political versus non-political nature of PEN. Young German writers, including Bertolt Brecht, told Galsworthy that the German PEN Club didn’t represent the true face of German literature and argued that PEN could not ignore politics. Ernst Toller, a Jewish-German playwright, insisted PEN must take a stand.

After the Congress Galsworthy returned to London and holed up in the drawing room of PEN’s founder Catharine Scott where he worked on a formal statement to “serve as a touchstone of PEN action.” This statement included what became the first three articles of the PEN Charter. At the 1927 PEN Congress in Brussels, the document was approved and remains part of PEN’s Charter today, including the idea that “Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.” The third article of the Charter notes that PEN members “should at all times use what influence they have in favor of good understanding and mutual respect between nations and people and dispel all hatreds and champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”

As the voices of National Socialism rose in Germany, PEN’s determination to remain apolitical was challenged though the determination to defend freedom of expression united most members. At the 1932 Congress in Budapest the Assembly of Delegates sent an appeal to all governments concerning religious and political prisoners, and Galsworthy issued a five-point statement, a document that would evolve into the fourth article of PEN’s Charter.

When Galsworthy died in January 1933, H.G. Wells took over as International PEN President. It was a time in which the Nazi Party in Germany was burning in bonfires thousands of books they deemed “impure” and hostile to their ideology. At PEN’s 1933 Congress in Dubrovnik, H.G. Wells and the PEN Assembly launched a campaign against the burning of books by the Nazis and voted to reaffirm the Galsworthy resolution. German PEN, which had failed to protest the book burnings, attended the Congress and tried to keep Ernst Toller, a Jew, from speaking. Some members supported German PEN, but the overwhelming majority reaffirmed the principles they had just voted on the previous day. The German delegation walked out of the Congress and out of PEN and didn’t return until after World War II. Their membership was rescinded. “If German PEN has been reconstructed in accordance with nationalistic ideas, it must be expelled,” the PEN statement read. During World War II PEN continued to defend the freedom of expression for writers, particularly Jewish writers. (Today German PEN is one of PEN’s active centers, especially on issues of freedom of expression and assistance to exiled writers.)

PEN was one of the first nongovernmental organizations and the first human rights organization in the 20th century. PEN’s Charter, which developed over two decades, was one of the documents referred to when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted at the United Nations after World War II. In 1949 PEN was granted consultative status at the United Nations as “representative of the writers of the world,” and is today the only literary organization with formal consultative status with UNESCO.

In 1961 PEN formed its Writers in Prison Committee to work systematically on individual cases of writers threatened around the world. PEN’s work preceded Amnesty, and the founders of Amnesty came to PEN to learn how it did its work.

Today there are over 150 PEN Centers around the world in more than 100 countries. At PEN writers gather, share literature, discuss and debate ideas within countries and among countries, defend linguistic rights and defend writers around the globe imprisoned, threatened or killed for their writing. The development of a PEN center has often been a precursor to the opening up of a country to more democratic practices and freedoms as was the case in Russia in the late 1980’s and in other countries of the former Soviet Union and in Myanmar where a former prisoner of conscience was instrumental in forming a center there and was its first President. A PEN center is a refuge for writers in many countries.

Unfortunately, the movement towards more democratic forms of government and freedom of expression has been in retreat in the last few years in a number of these same regions, including in Russia and Turkey.

For more than 35 years I have been engaged with PEN, as a member, as the President of one of PEN’s largest centers, PEN Center USA West during the year of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie and Tiananmen Square, as Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee (1993-1997), as International Secretary (2004-2007), and continuing as an International Vice President since 1996. I’ve also served on the Board and as Vice President of PEN America (2008-2015). I lived for six years in London, where PEN International is headquartered.

In the run-up to PEN’s Centenary, I was asked if I would write an account of PEN’s history as I’d seen it. I began by posting a blog twice a month, taking on small slices of the history in each narrative. This serial blog of PEN Journeys recounts PEN’s history as I’ve witnessed it as well as history of the period and personal history during those years. The narratives are framed by the times, featuring writers, including the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the protests in Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall—PEN members or future PEN members were central in all these events—the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of PEN Centers there; the opening up of Eastern Europe with its PEN centers; the release of PEN “main case” Václav Havel and his ascendency to the Presidency of Czechoslovakia; the mobilization of Turkish PEN members in opposition to recurring authoritarian governments; PEN’s mission to Cuba; PEN’s protests over killings and impunity in Mexico; protests and gatherings in Hong Kong on behalf of imprisoned Chinese writers; the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Peace to PEN member and Independent Chinese PEN Center founder and President Liu Xiaobo.

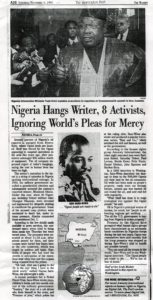

PEN and its members have played a pivotal role in defending freedom of expression around the world, in challenging systems that trap citizens, and in at least two instances, in taking on the presidencies of the new democracies that emerged. The PEN Charter, which sets out the principles and ideals, has united the global organization and guided its members who have often been at the forefront or in the wings of important historical moments—celebrated and outspoken writers like Václav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk, Yaşar Kemal, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Koigi wa Wamwere, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Arthur Miller, Anna Politkovskaya, Salman Rushdie, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Carlos Fuentes, Liu Xiaobo. The list is long, and I have had the privilege of interacting with many of them in PEN and also with hundreds of perhaps lesser known, but courageous writers who have stood watch and engaged.

The view of PEN Journey is global though the work is often local. As well as chronicling global events and personal history, PEN Journey recounts the shaping and re-imagining of this sprawling nongovernmental organization, one of the largest in terms of geographic reach. PEN has had to evolve and re-shape itself to serve its 155 autonomous centers. With at least 40,000 members around the globe in more than 100 countries, there are many stories others might tell, but this narrative is a close-up view of a period of time and of the writers who continue to work together in the belief that the world for all its differences and complexities can aspire to and perhaps even achieve “the ideal of one humanity living in peace and equality in one world.”* [*PEN Charter]

Because I tended not to throw away documents over the decades, I have an extensive paper as well as digital archive which I used to refresh memories and document facts. As I dug through files, I came across a speech I’d given which represents for me the aspirations of PEN, the programming it can do and the disappointments it sometimes faces.

At a 2005 conference in Diyarbakir, Turkey, the ancient city in the contentious southeast region, PEN International, Kurdish and Turkish PEN hosted members from around the world. The gathering was the first time Kurdish and Turkish PEN members shared a stage and translated for each other. I had just taken on the position of International Secretary of PEN and joined others at a time of hope that the reduction of violence and tension in Turkey would open a pathway to a more unified society, a direction that unfortunately has reversed.

PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman speaking at PEN International Conference on Cultural Diversity in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2005

The talk also references the historic struggle in my own country, the United States, a struggle which is ongoing. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Martin Luther King is quoted as saying. This is the arc PEN has leaned towards in its first century and is counting on in its second.

From Diyarbakir Conference:

When I was younger, I held slabs of ice together with my bare feet as Eliza leapt to freedom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.

I went underground for a time and lived in a room with a thousand light bulbs, along with Ralph Ellison’s INVISIBLE MAN.

These novels and others sparked my imagination and created for me a bridge to another world and culture. Growing up in the American South in the 1950’s, I lived in my earliest years in a society where races were separated by law. Even after those laws were overturned, custom held, at least for a time, though change eventually did come.

Literature leapt the barriers, however. While society had set up walls, literature built bridges and opened gates. The books beckoned: “Come, sit a while, listen to this story…can you believe…?” And off the imagination went, identifying with the characters, whatever their race, religion, family, or language.

When I was older, I read Yasar Kemal for the first time. I had visited Turkey once, had read history and newspapers and political commentary, but nothing prepared me for the Turkey I got to know by taking the journey into the cotton fields of the Chukurova plain, along with Long Ali, Old Halil, Memidik and the others, worrying about Long Ali’s indefatigable mother, about Memidik’s struggle against the brutal Muhtar Sefer, and longing with the villagers for the return of Tashbash, the saint.

It has been said that the novel is the most democratic of literary forms because everyone has a voice. I’m not sure where poetry stands in this analysis, but the poet, the dramatist, the artistic writer of every sort must yield in the creative process to the imagination, which, at its best, transcends and at the same time reflects individual experience.

In Diyarbakir/Amed this week we have come together to celebrate cultural diversity and to explore the translation of literature from one language to another, especially to and from smaller languages. The seminars will focus on cultural diversity and dialogue, cultural diversity and peace, and language, and translation and the future. This progression implies that as one communicates and shares and translates, understanding may result, peace may become more likely and the future more secure.

Writing itself is often an act of faith and of hope in the future, certainly for writers who have chosen to be members of PEN. PEN members are as diverse as the globe, connected to each other through PEN’s 141 centers in 99 countries. [Now 155 centers in over 100 countries.] They share a goal reflected in PEN’s charter which affirms that its members use their influence in favor of understanding and mutual respect between nations, that they work to dispel race, class and national hatreds and champion one world living in peace.

We are here today as a result of the work of PEN’s Kurdish and Turkish centers, along with the municipality of Diyarbakir/Amed. This meeting is itself a testament to progress in the region and to the realization of a dream set out three years ago.

I’d like to end with the story of a child born last week. Just before his birth his mother was researching this area. She is first generation Korean who came to the United States when she was four; his father’s family arrived from Germany generations ago. I received the following message from his father: “The Kurd project was a good one! Baby seemed very interested and has decided to make his entrance. Needless to say, Baby’s interest in the Kurds has stopped [my wife’s] progress on research.”

This child will grow up speaking English and probably Korean and will also have a connection to Diyarbakir/Amed because of the stories that will be told about his birth. We all live with the stories told to us by our parents of our beginnings, of what our parents were doing when we decided to enter the world. For this young man, his mother was reading about Diyarbakir/Amed. Who knows, someday this child who already embodies several cultures and histories, may come and see for himself this ancient city, where his mother’s imagination had taken her the day he was born.

It is said Diyarbakir/Amed is a melting pot because of all the peoples who have come through in its long history. I come from a country also known as a melting pot. Being a melting pot has its challenges, but I would argue that the diversity is its major strength. In the days ahead I hope we scale walls, open gates and build bridges of imagination together.

–Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, International Secretary, PEN International, March 2005

PEN Journey 41: Berlin—Writing in a World Without Peace

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I first visited Berlin in the fall of 1990 just after Germany reunited. I was living in London and took my sons, ages 10 and 12, to witness history in the making. I returned on a number of occasions, researching scenes for a book, attending meetings, and visiting German PEN in preparation for PEN’s 2006 Congress. Each time Berlin’s face was altered as the municipalities east and west moved to become one city again.

PEN International’s 72nd World Congress, Berlin, 2006

At the time of PEN’s Congress in May 2006, Berlin was bedecked with water pipes above ground—pink, green, blue, red—before the city buried its plumbing and infrastructure beneath the streets. Portions of the city had the appearance of an amusement park; there were also sections of the Berlin Wall with its colorful graffiti still standing, more as art exhibit than stark barrier to freedom.

“Welcome to a United Berlin” the German PEN President headlined his letter to the 450 delegates and participants for PEN’s 72nd World Congress. The Congress theme “Writing in a World Without Peace” was challenged by the reunification of Berlin and Germany, a historic event which bode well for the prospects of peace and which stood in contrast to the history that had come before. Yet the globe was still in conflict in the Middle East, in Asia and in Latin America where writers were under threat.

“There are countries such as Iran, Turkey or Cuba, where authors are jailed because of their books,” noted International PEN President Jiří Gruša. Resolutions at the Congress addressed the situations for writers imprisoned or killed in China, Cuba, Iran, Mexico, Russia/Chechnya, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and other countries.

Left: Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) meeting at Berlin Congress. Karin Clark (Chair WiPC) and Sara Whyatt (WiPC Program Director). Right: WiPC Conference in Istanbul: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN/PEN Board), Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Jonathan Heawood (English PEN), Notetaker

Two months before in March, over 60 writers from 27 PEN centers in 23 countries had gathered for International PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee conference in Istanbul where the WiPC planned a campaign against insult and criminal defamation laws under which writers and journalists were imprisoned worldwide. The conference also addressed the recent uproar over the Danish cartoons, impunity and the role of internet service providers offering information on writers, especially in China. A working group formed to support the Russian PEN Center which was under pressure from the Russian government.

Berlin, however, was sparkling and filled with the energy of reunification. “Today, this city—once separated by a Wall most drastically manifesting the division of Germany and Europe—has not only been re-established as the capital of Germany, but has simultaneously turned into a thriving meeting-place between East and West and North and South,” welcomed Johano Strasser, German PEN President. “Here in Berlin, history in all its facets—from the great achievements of German artists, philosophers and scientists to the crimes of the Nazis—has left its mark on the urban landscape.”

Left: German Chancellor Angela Merkel addressing PEN members at 72nd PEN Congress, 2006; Right: PEN International President Jiří Gruša speaking to PEN delegates and members at the Federal Chancellery; front row: German PEN President Johano Strasser, Chancellor Angela Merkel and PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman. [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

The keynote address by Nobel laureate Günter Grass challenged the conflicts around the globe and the countries engaged in them. “There has always been war. And even peace agreements, intentionally or unintentionally, contained the germs of future wars, whether the treaty was concluded in Münster in Westphalia, or in Versailles,” he said.

Nobel laureate Günter Grass addressing Opening Ceremony of PEN International’s 72nd World Congress in Berlin, 2006 [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As I sat on the dais on the edge of the stage listening to this renowned German writer, I leaned over to Jiří and said, If there is a standing ovation, I can’t stand. I was concerned. Grass could say and think whatever he wanted, but PEN was a non-political organization. Whatever my views of my country’s foreign policy, I was an American; I was also the mother of a son in uniform. Jiří leaned back to me and said in effect: Don’t worry, I won’t stand either. The speech ended with applause but no ovation, and then everyone got up and went to the next event.

It wasn’t my role to argue with Günter Grass even had the occasion allowed. But it was important that PEN assure the open space for debate existed which it did later in the Congress workshops and programs. PEN was filled with a multitude of points of view among its members; it did not have a litmus test of politics, only a commitment to the free expression of ideas. It offered a wide tent where views could be debated and challenged. Dogmatic political certainties often fell on their own in the alchemy of literature and imagination.

PEN members and delegates from around the world at Opening Ceremony of 2006 PEN Congress [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

Programs at the Congress also featured Nobel laureate and PEN International Vice President Nadine Gordimer and writers from around the world, including former International PEN Presidents Ronald Harwood, and György Konrád, Bei Dao, A.L. Kennedy, Margriet de Moor, Péter Nádas, Per Olov Enquist, Mahmoud Darwish, Duo Duo, Jean Rouaud, Johano Strasser, Veronique Tadio, Patrice Nganang and others. These writers participated in the literary events, including an evening of African literature and one of writers of German literature who had immigrated from abroad to Germany or had non-German cultural backgrounds. Afternoon literary sessions included prominent PEN writers introducing authors of their choice, an afternoon of essays and discussions on the theme Writing in a World without Peace and a lyric poetry afternoon.

PEN’s 85th anniversary coincided with the 60th anniversary of the United Nations. Both organizations had been founded after a World War out of an idealism that arose from desperate times with the hope that the future could be better than what had just transpired. “Both organizations were founded on a belief in dialogue and an exchange of ideas across national borders,” I noted in my address to the Assembly of Delegates. “When U.N. members were writing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the framers consulted, among other documents, PEN’s Charter.”

PEN also had a history with the city of Berlin, where PEN members had gathered in 1926 for the first international meeting of importance held in Berlin after World War I. At that Berlin Congress tensions had arisen among old and young writers, writers from the west and the east, and debate had flared about the political versus the nonpolitical nature of PEN. The debate that stirred in Berlin in part led to the framing of PEN’s Charter the following year.

Since those early days, PEN had grown in size beyond what the founding writers might ever have imagined. After the 2006 Berlin Congress, with the addition of centers in Jamaica, Uruguay, and Pretoria, South Africa, PEN had 144 centers in 101 countries in almost every time zone. The PEN world didn’t sleep. Someone, somewhere was always awake doing something. Through its centers PEN International participated in at least a dozen conferences around the world each year, including meetings of its standing committees. PEN thought globally but worked locally.

Berlin—with its own alterations and progress—proved a fitting location for the presentation of International PEN’s new Three-Year Plan. For the past decade, since the 75th Anniversary at the Congress in Guadalajara, PEN International had been in an organizational reformation. It now had a governing structure with a global Board that participated in decision-making; it had revised its Constitution and Rules and Regulations; it had developed a budget, increased its funding, and recently moved its offices into Central London to a larger space with cheaper pro rata rent and an elevator, which had meaning for anyone who had climbed the steep four (or five?) flights to PEN’s old offices. The staff size had also increased, and PEN had hired its first Executive Director, Caroline McCormick Whitaker, former Development Director from the British National History Museum.

International PEN Board meeting preceding 72nd PEN Congress in Berlin, May 2006. L to R: Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN), Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN), Kata Kulakova (Chair Translation & Linguistic Rights Committee), Sylvestre Clancier (French PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN), Chip Rolley (Chair Search Committee), Karen Efford (Program Officer), Caroline McCormick Whitaker (Executive Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary), Jiří Gruša (International PEN President), Peter Firkin (standing—Centers Coordinator), Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Jane Spender (Programs Director), Judith Buckrich (Women Writers Committee Chair)

Because British charitable tax law had changed, the opportunity had also arisen to unite International PEN and the International PEN Foundation into one charitable organization: International PEN, Ltd, a step that would provide the legal framework and protection for the organization and PEN’s name, would limit personal financial liability of the Board and attract a wider funding base. At the Berlin Congress, resolutions and approval were endorsed for this step which would be finalized the following year at the 2007 Congress in Dakar.

Caroline Whitaker took the Assembly of Delegates through the Three-Year Plan which had been developed after widespread consultation with PEN centers and the Board. She acknowledged that PEN couldn’t do everything that everyone wanted right away, that it was necessary to focus resources even as PEN developed more resources.

The Plan, which had grown out of all the discussions and preceding plans, concentrated on PEN’s three missions: to promote literature, to protect freedom of expression and to build a community of writers. “International PEN will work regionally to connect the activity of its many Centers around the globe on these issues,” Caroline told the delegates.

All PEN’s Standing Committees met at Berlin Congress—Writers in Prison Committee, Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee, Women Writers Committee and Peace Committee [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

In helping to develop PEN’s centers, the Three-Year Plan recommended International PEN focus on one region at a time, beginning with Africa where the 2007 PEN Congress would be held. International PEN would assist in programming and fundraising for development of PEN’s African Centers. The next regional focus would be Latin America, where PEN’s 2008 Congress was to be held. This rolling focus would allow the limited international staff to plan strategically. Regular daily work would still continue for the needs of centers in all regions.

PEN members met in workshops at 72nd Berlin Congress. Topics: PEN in the World—Global Issues; Education; the Strategic Plan; Centers; Networks and Partners; Asia and Central Asia; Middle East; Africa; Europe and Americas [Photo credit: Tran Vu]

As International PEN’s work had taken me across the globe that year, I’d come to see that PEN and its members formed a kind of intricate net which helped hold civil society together, the kind of sturdy net used on hills to prevent landslides. In a way that is what PEN members did around the world. They helped prevent literary culture and languages and freedom of expression from slipping away by both their active programming and their defensive actions

At the 1926 PEN Congress in Berlin International PEN’s President John Galsworthy and PEN’s founder Catherine Amy Dawson Scott had their voices recorded and preserved in a project of the German state. Galsworthy read a page from his Forsyte Saga. According to Dawson Scott’s journal, she recorded the following: “Even as individuals become families and families become communities and communities become nations, so eventually must the nations draw together in peace.”

It was a worthy, if not yet realized goal, but at least in PEN we had a global family.

Mayor’s reception for PEN members and participants at 72nd World Congress in Berlin, May 2006 [Photo Credit: Tran Vu]

Elections at 2006 Congress:

International PEN President: Jiří Gruša was re-elected for further 3-year term.

International PEN Board: Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian Center) and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN re-elected to the Board)

Vice Presidents: Toni Morrison (American PEN) and J.M. Coetzee (Sydney PEN) elected Vice Presidents for service to literature and Gloria Guardia (Panamanian Center) for service to PEN

Women Writers Committee: Judith Buckrich (Melbourne Center) re-elected as Chair

Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee: Carles Torner (Catalan PEN) stood down as Vice Chair, replaced by Josep Maria Terricabras (Catalan PEN)

Next Installment: PEN Journey 42: From Copenhagen to Dakar to Guadalajara and in Between

PEN Journey 38: PEN’s Work On the Road in Kyrgyzstan and Ghana

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

There have been a number of conferences and a few Congresses in PEN I’ve regretted not being able to attend. One was the Women’s Committee conference June 2005 in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan right after the 71st Bled Congress. As International Secretary, I have notes and reports from that conference. Nine years later in the fall of 2014, PEN held its 80th World Congress in Bishkek, a Congress I did attend. The Women Writers Committee led the way for International PEN into Central Asia. Later in 2005 members of the Women Writers Committee also met at the International PEN conference in Ghana which I did attend.

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, site of PEN International’s Women Writers Meeting in June 2005 and Accra, Ghana, site of PEN International’s African conference and also meeting of African women writers, November 2005.

First, Bishkek: The President of Bishkek PEN Vera Tokombaeva was concerned about the circumstances of writers in Central Asia since the breakup of the Soviet Union. She suggested to the new Women Writers Committee (IPWWC) chair Judith Buckrich that PEN hold a women writers meeting in Bishkek. Many of the institutions which had enabled writers to publish had vanished, and the status of women in the region had grown worse. Young writers from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan who were members of the PEN center were troubled by the decrease in the number of women working creatively. Only a handful were left.

PEN Women Writers Committee Chair Dr. Judith Buckrich and International PEN Board member Judith Rodriguez (Melbourne PEN)

Bishkek PEN did a study highlighting the problem. Central Asian women writers were struggling with poverty, it said, and literature was no longer published unless self-published with limited distribution.

“Women writers are now mostly on their own. They have fallen into a cultural vacuum,” the conference proposal noted. “They are not in contact with colleagues outside their own country and know nothing of the state of culture in the world. In the meantime the global community has begun to pay attention to Central Asia because its difficult geopolitical situation could lead to the rise of violent, ultra-religious and fundamentalist ideologies into the area. And it is partly the lack of modern local literature that makes the region a breeding ground where alien ideologies can take root among young people. Flourishing modern literature could be the means to disseminate democratic ideas and social awareness.”

International PEN raised funds for the conference whose theme was “Women and Censorship.” Women from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan as well as from Finland, Norway, Switzerland and Australia gathered. The discussion focused on the access to education for women, access to literature and the formation of support groups and publishing cooperatives within and outside the region and ways to overcome censorship and self-censorship. The group addressed external pressures on what women should write and considered ways and means to access funding for women writers.

Attendee Kristin Schnider, President of Swiss German PEN, noted, “Following the discussion on the main topic, women and censorship in Central Asia, I learned just how hard it is for the strong and determined women I met to overcome censorship and self-censorship within their societies…First and foremost a woman is perceived as a mother and wife, tending the family. So much so that women feel they are confronted with the choice between being either creative or getting married. Women are not supposed to enter politics…[and] if women insist on writing they are supposed to stick to detective stories or romantic topics.”

In a discussion “The Situation in Central Asia: Women and Society and Economic Censorship,” moderator and documentary film maker Dalmira Tilepbergenova from Kyrgyzstan, noted: (translated from Russian)

“Patriarchy foundations have always been strong in Asia…My disclosing of gender inequality by the example of cinematograph is not casual. Because firstly cinematograph is a corporative sort of creative work and thus the problem of relations between men and women shows very clear and strikingly there. Second, I as a film director have to constantly deal with the problem of my work. Since Kyrgyzstan became independent, our cinematograph has passed through the period of its clinical death to its reestablishment. New names have already appeared and new films have been shot. But strange relations between our cinematograph and gender policy have existed up to now. Unwillingness of men to see women in the spheres usurped by men occur…instinctively. And this instinct is as strong as the instinct of self-preservation. Firstly, when the woman is engaged on an assisting job position in our cinematograph, everything seems to be all right. But as soon as the woman shows a desire to make films independently, the friendly atmosphere of men around her turns into syndicate of plotters. Men at once start to blame the woman for her excessive ambitions, incompetence, and uselessness. Men also criticize her private life. The woman’s desire to make films is considered as diagnosis of having deficit of sex.”

IPWWC Chair Judy Buckrich of Melbourne PEN reported the Bishkek conference was “a fantastic opportunity,” and said the committee had already begun planning for a meeting of women writers on the African continent to follow the Senegal PEN Congress in 2007. “The meetings are important in expanding the horizons of PEN to women who are not members of PEN but who PEN supports as part of its belief to support writers in difficult circumstances,” she noted.

Women Writers meeting at 2005 PEN Ghana conference including Veronica Uzoigwe (Nigerian PEN), Zeinab Koumanthio Diallo (Guinean Center), Ekbal Baraka (Egyptian PEN), Muthoni Likimani (Kenyan PEN), Kristin Schnider (Swiss German PEN), Caroline McCormick Whitiker (PEN International Executive Director), Jane Spender (PEN International Programs Director), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (PEN International Secretary/American PEN)

In December 2005 International PEN’s conference in Accra brought together 36 writers, a number of them women, from 13 of PEN’s 17 African Centers to prepare for the 2007 Senegal Congress. Supported by UNESCO and hosted by Ghanaian PEN, the conference aim was to begin developing a plan for sustained programs and collaboration among the African centers and to select a theme for the Congress. While PEN Senegal would act as the host center, the World Congress was a joint effort of PEN’s PAN African Network. African members of the Women’s Committee held an additional meeting to address the challenges facing women writers in Africa and to plan for the larger IPWWC conference in 2007.

In preparing for the Ghana conference, I returned to the shelves of African literature I’d read years before and pulled some of the books which first took me to Africa before I ever arrived on the continent—Ama Ata Aidoo’s No Sweetness Here, Ayi Kwei Armah’s Fragments, Charles Mungoshi’s Waiting for the Rain. In my address to the conference, I included a quote from Ghanaian writer Kofi Anyidoho’s prose poem Akofar only to discover when I arrived that Kofi Anyidoho was on the program.

Speaking Ghanaian Professor and poet Kofi Anyidoho, seated Frankie Asare-Donkoh, Secretary PEN Ghana

From Akofar:

Words are birds. They fly so fast too far from the hunter’s aim. Words are winds. Sometimes they breeze gentle upon the smiles our hearts may wear for joy; they fan the sweat away from fever’s brow; they lull our minds to sleep upon the soft breast of earth. Yet soon too soon words become the mad dreams of storms. They howl through caves through joys into shrines of thunderbolts. They leave a ghost on guard at memory’s door. Therefore gently…gent-ly…Akofa, gen-t-ly…Take care what images of life your tongue may carve for show at the carnival of weary souls.”

The poem spoke to the themes and mission of PEN and the gathering of writers who understood that words transport over time and place and history, that words cross borders and have the power to connect us to each other and to ourselves. It is words, shaped into images and ideas, that survive wars and famine and political unrest if we are vigilant and protect them and circulate them and translate them.

Top to Bottom: Zeinab Koumanthio Diallo (Guinean PEN), Frankie Asare-Donkoh (Ghanaian PEN), Veronica Uzoigwe (Nigerian PEN)

I also quoted from Ghanaian poet Ayi Kwei Armah’s Fragments:

“Where are you going,

go softly.

Nananom,

you who have gone before,

see that this body does not lead him

into snares made for the death of spirits.

You who are going now,

do not let your mind become persuaded

that you walk alone.

There are no humans born alone.

You are a piece of us,

of those gone before

and who will come again.

A piece of us, go

and come a piece of us.

You will not be coming,

when you come,

the way you went away.

You will come stronger,

to make us stronger,

wiser,

to guide us with your wisdom.

Gain much from this going.

Gain the wisdom

to turn your back on the wisdom

of Ananse.

Do not be persuaded you will fill your stomach faster

if you do not have others’ to fill.

There are no humans who walk this earth alone.”

The poem reflected the aspiration of PEN and the meeting among participants who, as writers, often did work alone, yet understood we were all part of a larger community. For any community of letters to thrive and survive, the freedom of the individual writer had to be protected.

At that time in Africa over 230 writers in 34 countries were listed as PEN cases, excluding Egypt, which was counted in the Middle East, though the President of Egyptian PEN also attended the meeting. The large majority of cases were journalists arrested as critics of the authorities or as whistleblowers on corruption. Journalists also ran afoul of the “insult laws” which were on the books in 45 of the 53 African countries. Because of the difficult state of publishing in Africa, journalists were the group of writers with realistic possibilities of being published. Countries of most concern then were the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Libya, Somalia, Tunisia and Zimbabwe, none of which had active PEN centers, though a Somali-speaking PEN center did exist in London, and Zimbabwe PEN had existed but was inactive with its President poet Chenjerai Hove having to live in exile. (Today there are PEN centers in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, and Tunisia though the situation in some of the countries remains problematic.)

The Network of African Freedom of Expression Organizations (NAFEO) had formed just two months before the conference with 33 freedom of expression organizations attending a press freedom conference in Ghana. The aims of the network were similar to PEN’s whose Writers in Prison Committee would interact and assist when the network began to function.

The attendees at the Ghana conference shared experiences of their PEN centers, particularly in providing writing and reading programs in schools. Ghana PEN had a robust program in the schools as did other centers. The delegates agreed that the goals and work of PEN in Africa should include expanding freedom of expression, helping to lower barriers to publishing and disseminating African literature, cultivating new voices and increasing access to literary creation. The means to achieve these goals were part of the discussion, including cultivating new voices by working with youth writing clubs, bolstering recognition and excellence in literature by awarding literary prizes. Delegates planned for these discussions to continue among the African PEN Centers, facilitated when possible by International PEN. They also planned to expand the ideas and work at the 2007 PEN Congress.

Writers and visiting students at 2005 PEN International Conference in Accra, Ghana. African PEN Centers attending conference: African Writers Abroad, Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somali-Speaking, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia as well as American and Swiss German and International PEN facilitating and note taking.

Ghana PEN organizers Frankie Asare-Donkoh, General Secretary and Frank Mackay Anim-Appiah, President with PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman

During the Ghana conference the possible theme for the 2007 Congress was debated and discussed, including:

—Literature and the Environment/ Literature and Ecology

—Literature and Emancipation (women, political, financial)

—Freedom of Expression and Conflict Prevention

—African Writing in a New Age, In and Out of Africa

—The Role of Literature in the Creation of Peace (with sub-themes “The crisis of reading and readership” and “Literature for children”)

—Writers Role in Peace Building in Africa and World & Literature

—Literature and the Oral Tradition (with the subtheme of the environment)

—The Writer’s /Literature’s Role in Peace-building in Africa and the World

—Literature of Exiles/ Exile Literature

—The Roles of Literature and Publishing

—The Word, the World and Human Values

—Challenge of African Literature Today

—Being a Writer in Africa

—Writer in Age of Globalization (cultural diversity)

—Survival of Literature in New Millennium

—African Writing in New Age: In and out of Africa

—Writers and Prevention of Conflict

—Writers in Their Role in Encouraging and Promoting Literacy in Africa (Responsibility and Role of Writer)

—Literature and Conflict management in Africa and the World

—Freedom of Expression and Global Diversity

—Writers in a World in Crisis (diversity, literacy etc)

The theme finally agreed for the 73rd PEN World Congress in Dakar was: The Word, The World, and Human Values.

Elmina Castle, built in 1482 as Portuguese trading settlement, became principle holding prison for slave trade on Cape Coast, Ghana for three centuries.

The highlight of the conference was a long road trip to Cape Coast (also known as the Gold Coast), where the first European (Portuguese) explorers arrived in the 1400s. The Portuguese built the Castle of Elmina there which still stands on the rocks above the sea. In this new/old land the Portuguese discovered gold and also began acquiring human beings to trade for European goods. British, Dutch, Danish, Prussian, and Swedish traders soon followed and built other forts along the coast. Elmina Castle was turned into a prison for men and women who were sent shackled through “the door of no return” into slavery. From this point, as well as from Gorée Island off the coast of Dakar, Senegal, the slave trade flourished for centuries as European and other traders sold men and women and goods into the Caribbean and North and South America.

“Slave Exit to Waiting Boats” in Elmina Castle, Cape Coast, Ghana; Kadija George, President of African Writers Abroad Center standing in front of a “door of no return.” The back of her shirt reads: “Literature is the most beautiful of countries.”

The ghostly white fort of Elmina with its iron-barred cells with peep holes to the ocean facing west and the crashing surf on the rocks silenced us as we moved through these portals of history. The several hour ride back to the city was much quieter than our impatient journey to the Coast.

In Tanzania an exchange between poet and audience in the oral and performed poetry often begins:

“I give you a story.”

Audience: “I give you another.”

“I came and I saw.”

Audience: “See so that we may see.”

This power to see and invoke, to enter the rhythm of the human heart and dance there for a time with another as partner is what literature does and what PEN celebrates and tries to protect.

Next Installment: PEN Journey 39: Spiritus Loci—Literature as Home

PEN Journey 31: Tromsø, Norway: Northern Lights

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

The week before PEN’s 70th World Congress in Tromsø, Norway in the Arctic Circle, my oldest son competed in the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, the only wrestler to qualify for TeamGB (Great Britain). He had dual citizenship and was the first British champion to qualify for the Olympics in wrestling in eight years. In his sport, there was no seeding of competitors; instead, after making weight, each wrestler reached into the equivalence of a hat and drew their first round competitions. True to his history, my son drew the best opponents. As one news commentator noted: “Coming to the mat is Nate Ackerman, born in the US, wrestling for Great Britain, getting his PhD in mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology…but that won’t help him now as he faces the three-time World Champion from Armenia.” My son lost to the Armenian wrestler. His other opponent was the world bronze medalist from Kazakhstan who went on to win the silver medal at the Olympics. Though my son didn’t win either match, he also didn’t get pinned, and he wrestled nobly. The Olympic Games in Athens was a magical time.

Olympic circles projected in light on the Acropolis at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens

I was heading to Tromsø with a smile inside, though behind my smile was also a quiet attention that never left me for my youngest son, a Marine, was in Anbar Province, Iraq that summer, patrolling in 120° and alert for IED’s and snipers along the roadside. He had missed his brother in the Olympics and his brother missed being able to talk with him.

As I changed planes in northern Europe, I realized I was going to need a coat in the Arctic Circle and bought a light foldable one at an airport shop which I took to a decade worth of PEN Congresses after. On the plane I reviewed the stack of PEN papers and resolutions.

I was arriving at the Congress having agreed to stand for International Secretary. (See PEN Journey 30). The other PEN member standing was Giorgio Silfer, a poet and playwright and president of Esperanto PEN.

Norwegian PEN hosted over 300 writers, editors, and translators from at least 60 countries for the 70th World Congress whose theme was Writers in Exile—Writers in Minority Languages. The Rica Arctic Hotel where we stayed and met was an easy walk to the small downtown of Tromsø, capital of northern Norway, well above the Arctic Circle and called “the Paris of the North.”

Kjell Olaf Jensen, President of Norwegian PEN, reminded delegates that the Congress themes reflected the literary scene of Tromsø, which would soon join the International Network of Cities of Asylum as the fifth Norwegian city. (This network later developed into the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) in 2006 with PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee as a partner and with the inaugural meeting in Stavanger, Norway.) One of the guiding voices in the exile network Professor Ole Danbolt Mjøs, director of Tromsø University’s Peace Center and President of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, spoke at the Welcome Party Ceremony as did Ole Henrik Magga, President of the Sami Parliament. Half of the estimated 50,000 Sami in the world lived in Norway. Crown Prince Haakon of Norway officially opened the Congress the next day noting, “Freedom of speech is a source of power. If used constructively, it is amazing what speech can do. It can fight corruption, free political prisoners, and make oppressive regimes crumble.”

The two themes of writers in exile and writers in minority languages intertwined throughout the Congress with readings and round tables at cafes and pubs in the midst of Tromsø’s annual International Literary Festival and the International Nana Festival of Aboriginal people. Literary and musical programs included the Sami singer Mari Boine in the Arctic Cathedral and the work of the celebrated but deceased Sami poet, singer, and writer Nils Aslak Valkeapaa. PEN’s programs highlighted some of Norway’s own writers in exile: Mansur Rajih from Yemen, Soudabeh Alishahi from Iran, Islam Elsanov, a film maker from Chechnya, and Chenjerai Hove from Zimbabwe as well as guests Reza Baraheni (Iranian writer living in Canada), Turkish activist Şanar Yurdatapan, and former Russian prisoner and writer Grigory Pasko.

A conference at Tromsø University under the theme “Should Writers Live in Prison?” preceded the Opening Ceremony. Storyteller Easterine Iralu of the “Nagaland nation” addressed the delegates in the main lecture hall: “Every man is a story and every nation is a bristling galaxy of stories. Every nation should be given the right to tell the story by its own story tellers…We are an oral society. Naga writing is an aboriginal achievement.”

New PEN International Secretary Joanne Leedom-Ackerman and PEN International President Jiří Gruša at 70th PEN Congress in Tromsø, Norway, 2004

In later panels Lebanese novelist Amin Maalouf said, “Poets and writers must reinvent the world. This is not a task to be left to politicians. Is this a century of bombs or poems?” Norwegian bestselling author Jostein Gaarder expanded the questions: “How wide are the ethical horizons of literature and art? The question for writers and artists at the start of the third millennium must be what shift in consciousness do we need? Literature is nothing less than a celebration of mankind’s consciousness. So shouldn’t an author be the first to defend human consciousness against annihilation?”

At his first Congress as PEN International President Jiří Gruša told the delegates, “I myself have experienced persecution and really esteem people who help authors to freedom. I know how vital it is to have somebody outside the prison who cannot be stopped. ” He challenged writers to invent and combine practical and stylistic literary methods “to conquer plagues and pestilence that threaten human, moral and planetary evolutions.” He and the delegates of the Congress condemned recent terrorist attacks on a school in Beslan, Russia which had taken the lives of hundreds of children just a few days before. Jiří also paid respect to poet, Nobel laureate and PEN member Czeslaw Milosz, who had recently passed away. “It is with deep grief that the PEN family sympathizes with the people of Poland. We shall miss him, but his work will continue to inspire people from one end of the world to the other.” Milosz was a member of the Writers in Exile American Branch of PEN.

Writers in Prison Centre to Centre newsletter featuring poem by Grigory Pasko, honored guest at 70th PEN Congress and article about prisoner Nasser Zarafshan.

In addition to attending the rich literary panels and discussions, PEN’s Assembly of Delegates passed a resolution that urged authorities to assist in freeing Christian Chesnot and Georges Malbrunot, two French journalists currently held hostage in Iran. Encouraged by Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal, delegates and participants also signed a petition to the Islamic Republic of Iran demanding that Dr. Nasser Zarafshan’s life be protected and that he be immediately and unconditionally released. Delegates also signed a petition to the President and Government of Russia calling for a multilateral dialogue and an end to the violence in Northern Caucasia and a restoration of civil living conditions in the Chechnyan Republic, including open access so that local and national media could report events in the region. (Chesnot and Malbrunot were released from Iran a few months after the Congress, in late December, 2004. Zarafshan was not released until 2007.)

The Assembly passed resolutions from the Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee (TLRC) urging authorities of the Russian Federation to grant cultural rights to all minorities, including use of regional languages, and the same appeal was sent to authorities in Turkey, Iran and Syria regarding Kurdish language and culture.

Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) resolutions which the Assembly passed focused on the repression of free expression for writers seeking asylum in Australia, on harassment of certain journalists in Canada, attacks on writers in Chechnya, imprisonments in China and Cuba, censorship and harassment of writers in Egypt, arrests in Eritrea, hostage-taking in Iraq, detentions in the Maldives, killings in Mexico, detention and ill treatment in Myanmar, murder in Nepal, killing and disappearances in Russia, bombings and assassinations in Spain, imprisonments in Turkey, restrictions on the free flow of international writing in the U.S., imprisonments in Uzbekistan and Vietnam, and restrictions on free expression in Zimbabwe.

Administrative Director Jane Spender and PEN International Secretary Terry Carlbom at 70th PEN Congress in Tromsø, Norway, 2004

The WiPC resolutions had been discussed at the earlier Writers in Prison Committee meeting where a new chair had been elected from four candidates. Karin Clark of German PEN would replace Eugene Schoulgin, who was stepping down after four years and was running for the Board of International PEN.

At the Assembly of Delegates, Eugene introduced guest of honor, former Russian main case and journalist Grigory Pasko, who told the delegates that “although he had not been able to thank all those who had worked on his behalf while he was in prison, he now would like to thank everyone again and again. Unfortunately he could not now say that Russia had become more democratic, but he would continue to fight to make it so, supported by all his friends in the Assembly hall.”

Election for the Board of PEN included eight candidates for three open positions. Eric Lax (PEN USA West), Judith Rodriguez (PEN Melbourne), and Eugene Schoulgin (Norwegian PEN) joined the Board. Three new centers—Basque, Guatemala and Kosovo—were admitted into PEN.

At his last Assembly as International Secretary Terry Carlbom told the delegates, “Our greatest strength is ultimately our capacity for empathy, compassion and solidarity. Ours is not the solidarity of the collective herd; it is the solidarity of the concerned and caring individual, a solidarity with a fragile world and fragile civilization. And the solidarity that sometimes can provide comfort in the rather lonely process of creative writing…I have been proud to serve.”

At the Congress Terry saw the passage of the final amending resolutions on the Regulations and Rules of Procedure he had dedicated a significant portion of time to as International Secretary. Updating rules and regulations to bring them in line with the changes PEN had made to its governance was not a task for many writers. I was grateful to Terry that these documents were now drafted and a working document for strategic planning was in hand.

The election for Terry’s replacement as International Secretary was between Giorgio Silfer (Esperanto PEN) and myself. Giorgio’s speech to the Assembly was a poem, an unusual and memorable presentation for office. Giorgio was a linguist and a poet and participated actively on the Peace Committee and Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee. I was a novelist and journalist and activist on the Writers in Prison Committee and Women’s Committee. We had both worked with all committees, but we had our corridors and respected each other. My statement was more traditional.

I was elected the new International Secretary of PEN. I glimpsed the work ahead when I sat down with Terry in the hotel lounge after the election. He told me in November I needed to be at Senegal PEN‘s conference with African centers in Dakar in preparation for the 2007 PEN Congress there, and in the spring I was in charge of a conference PEN was holding in Diyarbakir, Turkey with Kurdish and Turkish PEN. Great, I said. Can you show me the budget and program for the Diyarbakir conference? Terry explained that we didn’t have a budget yet, but he offered to continue helping with this conference. I was to learn quickly that unlike the Writers in Prison Committee, the rest of International PEN worked in a more unstructured fashion, without clear budgets but with relationships that usually came through. I began making lists. My tenure as International Secretary would include notebook after notebook of lists of tasks to be done.

A solace as I left that meeting was that I would be working with Jane Spender, Administrative Director, who was smart, a friend, and had gotten PEN through remarkably tight places before. Jane and I both knew that time was not on our side if we didn’t modernize further. I put on my new PEN coat and went for a brisk walk with Jane in the drizzle towards the next venue. PEN International had been asked for the first time by a major funder to provide an evaluation of a major grant. No one before had asked that of PEN, but it would surely be asked more and more in the future. We walked down the wet Tromsø streets considering what was before both of us. We had to figure out how to do an evaluation and much more…

Next Installment: PEN Journey 32: London Headquarters: Coming to Grips

PEN Journey 26: Macedonia—Old and New Millennium

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

I remember diving from a rowboat into Lake Ohrid and swimming in pristine water. I love to swim but never did so at PEN Congresses. However, the 68th Congress was held on one of Europe’s oldest—3 million years old—and deepest lakes which floated in the mountainous region between North Macedonia and eastern Albania. The water was the cleanest I had ever seen or felt. I swam without looking back until finally, I heard a voice from the boat shouting, “Come back! You’re almost in Albania!”

Moments before Isobel Harry (l) (Canadian PEN) and Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (r) (American PEN) dive into Lake Ohrid for a swim between meetings at the 68th PEN Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia in 2002

Albania, or rather the Albanian Liberation Army, a paramilitary organization, had recently been in conflict in Macedonia and was the reason PEN’s Congress there had been postponed the year before. (PEN Journey 25)

Swimming with me was my friend Isobel Harry, Executive Director of Canadian PEN, and in the boat sat Cecilia Balcazar from Colombian PEN and another PEN member. They watched over us in this break from the PEN meetings. My memories of the 2002 PEN Macedonia Congress include intense meetings of the Assembly in the Congress Hall of the old Soviet-style Metropol Hotel and neighboring Bellevue Hotel conference center and relaxed gatherings afterwards at lakeside cafes in the town of Ohrid, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

PEN colleagues at a lakeside cafe during the PEN Congress in Ohrid, Macedonia. (L to R) Dixie Willis and Sara Whyatt (WiPC staff), Susie Nicklin (English PEN), Eugene Schoulgin (Norweigan PEN & WiPC Chair), PEN member, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Vice President & American PEN), Niels Barfoed (Danish PEN), Isobel Harry (Canadian PEN), Fawzia Assaad (Swiss Romand PEN), Victoria Glendinning (English PEN), Carles Torner (PEN Board & Catalan PEN)

In the evenings we gathered for literary events with UNESCO-like titles—The Future of Language/Language of the Future and Borders of Freedom/Freedom of Borders. These were also the themes of the Congress. There was music and poetry in Macedonian and other languages I didn’t understand, recited in cavernous, shadowy chambers, including in the ancient Cathedral Church of St. Sophia, a structure from medieval times, rebuilt in the 10th century. Its frescoes still adorned the walls from Byzantine times in the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries and had been restored after the church was converted to a mosque during the Ottoman Empire.

While current politics and conflicts occupied the daytime work of PEN, history suffused the gathering. Civilization in Ohrid dated to 353 BC when the town had been known as “the city of light.”

Cathedral Church of St. Sophia in Ohrid

“The old millennium, especially in ‘old’ Europe, should, I believe, be left behind with all its anachronistic boundaries—geographical, historical, racial, ethnic, state, linguistic, religious and cultural—and give way to the unfolding of the new millennium, to its open-mindedness and tolerance,” Dimitar Baševski, President of Macedonian PEN, wrote in his introduction to the Congress. “For generations we in Macedonia have lived with a creed according to which culture and not warfare or power is perceived as the field for competitiveness among nations. The aims of the World Congress of International P.E.N. in 2002 perfectly correspond with the spirit of this creed.”

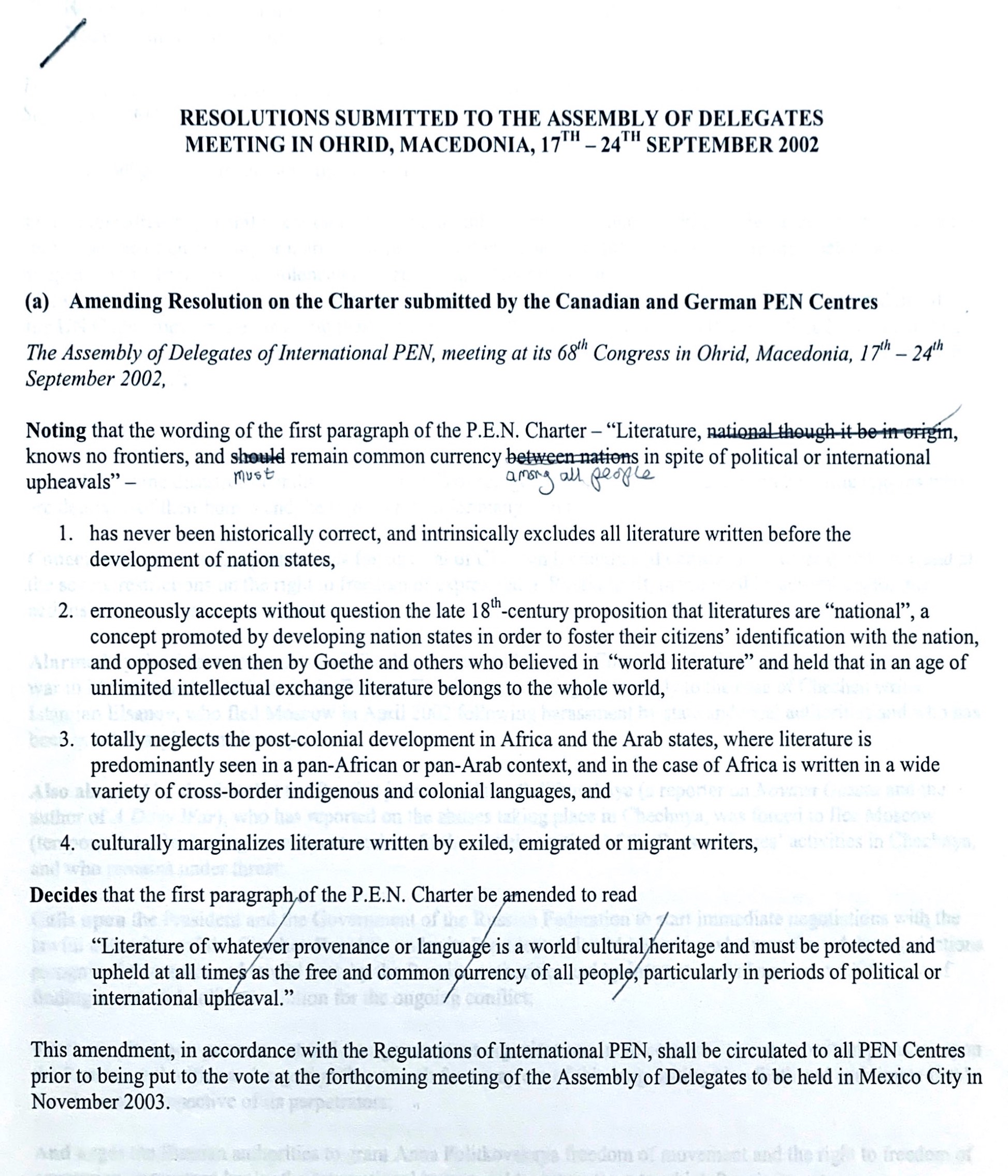

Over 300 people from 69 PEN Centers gathered in the hills of this North Macedonian city for the 68th World Congress. The Congress’ work included the activities and reports of PEN’s committees—Writers in Prison, Peace, Translation and Linguistic Rights, Women’s, Exile Network—and the PEN Foundation, PEN International Magazine, and PEN Emergency Fund. There was a proposed revision to PEN’s Charter removing the concept of literature as being national in origin; there was the introduction of new centers, the dissolution of inactive centers and the elections for the Board, Vice Presidents, and Search Committee. There was a report from the International Secretary on the renewal of PEN’s “formal consultative relations” with UNESCO for a further six years, a step that acknowledged PEN as the only voluntary organization and the only literary organization in this category and one of only 12 organizations with a “Framework Agreement.” PEN had also been reclassified as a Category II organization with ECOSOC (United Nations Economic and Social Council) which included organizations with “special competence in specific areas” such as Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, a category that reflected PEN’s status and contribution as the only world writers organization within the UN system. At PEN’s Assembly of Delegates attention was called to a dozen PEN conferences—last year’s and the year ahead—and finally the Assembly passed Resolutions from the Writers in Prison Committee and Peace Committee on the situations in Russia and Chechnya, Russia itself, the Middle East, Belorussia, China, Colombia, Cuba, Iran, Turkey, Zimbabwe, Uighur Writers, and Tatarstan

The aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on the United States the year before remained a focus that was altering the security landscape for nations around the world and for writers. PEN President Homero Aridjis observed, “Today our world is teetering on the brink of war.” He added, “In search of security, there have been encroachments on privacy and intrusive measures threatening freedom of expression and the right to dissent and criticize, but the global reach of information seems to have accelerated, proof of which is the current effort by the Chinese government to block its citizens’ access to the search-engine Google.”

“How can PEN and writers bring about positive changes?” he asked. “For a start, we could promote freedom of expression in Afghanistan. Not that long ago we were signing Internet petitions protesting against the treatment of women by the inhumane Taliban regime and begging the Taliban not to dynamite the colossal Buddhas of Bamiyan. Now I ask you to help me identify and approach Afghani writers who would be willing to found a PEN Center in Afghanistan and to try and find ways of giving this fledgling Center the means to thrive.”

[With the help of Norwegian PEN and others, an Afghan PEN Center was in fact founded with men and women writers from all ethnic groups and was voted into PEN at the 69th Congress the following year in Mexico. Writers in Prison Committee Chair Eugene Schoulgin played an instrumental role in working with and facilitating support for the Afghan writers.]

At the Macedonia Congress Eugene reported, “In my speech in London last November I mentioned the threats to the freedom of expression I feared that would follow the events of 9/11 in the US. What has happened last year has unfortunately proved these fears were well founded. Today over 40 countries have imposed new legislation on their populations which clearly weaken their human rights. New Anti-terror laws have been established in Canada, USA, UK, France, EU as a whole, Jordan, India and New Zealand. Terrorism laws expanded on Cuba and on Italy and in Colombia, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Israel, Russia, Uzbekistan, China and in the Philippines, and terror laws have been used as an excuse to crack down on the opposition and on minorities inside their regions. This in combination with the threats of a new war on Iraq makes the present situation extremely worrying, and will most certainly give us in the WiPC reason to be even more vigilant in the year to come.”

Visiting the WiPC Committee at the Congress were two former PEN main cases—Eşber Yağmurdereli, Turkish poet/dramatist and lawyer, who was blind and spent 14 years in prison and whom a number of us had met in Istanbul at a Freedom of Expression Initiative a few years before and Flora Brovina, a Kosovair/Albanian poet and doctor who had been abducted by Serbian troops and imprisoned in Belgrade during the NATO bombing. Flora’s son had contacted PEN which sent out an urgent appeal about her abduction. I had met her husband and family when I visited Pristina, Kosovo the year before with the International Crisis Group while she was still in prison. This was the first time I met Flora, who had become an internationally celebrated case and was a member the country’s Assembly. She told the Writers in Prison Committee that every letter sent to the prison by PEN served as another attempt to tear down the walls of the prison.

Esber Yagmurdereli said at present there were around 10,000 prisoners accused of being “terrorists,” but 90% of these should be considered prisoners of conscience, and many were simply students. “On 19 December 2000, the 20th day of the protest, I was playing chess with my friend in my cell,” he said. “He was a university student named Irfan. He was my son’s age–21 or 23 years old. He defeated me three tims. He said you are 60 years old. There are so many of us whose cases ar not covered in the press, but you do get attention. We need you as much as you need us. Then came the teargas. The protests took three yours. I myself lost consciousness and came to about an hour later. I learned that 32 people had been killed–burned to death. I learned that my friend Irfan was one of them.”

Russian journalist Anna Politkovskya also attended the Macedonian Congress. She told the WIPC meeting that she got threats from criminals, military and government. “I could stay in Vienna or elsewhere in the West, but it is my decision to be in Russia because I understand more than other people that if I couldn’t write articles or give radio talks, there would be no information about Chechnya,” she said. “Because travel to Chechnya is illegal, I need to prepare my trips as if I were a spy. I have to be strong, as far as I can. My children are in Moscow, and they are also threatened. ” My last meeting with Anna was sharing thick coffee at a tiny airport café in Skopje on our way home from the Congress.

Resolution for change in wording of PEN’s Charter; amended wording, noted and approved, proposed by English PEN president Victoria Glendinning. Final proposal and approval to take place at Mexico Congress in 2003.

In addition to its traditional work, International PEN was proceeding with modernizing its governance and structure, led by International Secretary Terry Carlbom and the Board of PEN. Deputy Vice Chair of the Board Carles Torner reported that this included the restructuring of PEN and the PEN Foundation as British charitable tax law was changing; also new roles for the Vice Presidents were being considered; a modest change in the Charter was proposed for this Assembly to be confirmed at the next year’s Congress in Mexico, and the Treasurer was proposing a new international dues structure with a graded system, raising dues for centers from wealthier economies and reducing dues for others, based on the World Bank system of four categories. The change in the dues structure was unanimously approved.

Elections at the Congress included two new Vice Presidents Lucina Kathmann (San Miguel Allende PEN) and Boris Novak (Slovene PEN) and new Board members Takeaki Hori (Japan PEN), Cecilia Balcazar (Colombian PEN), Sibila Petlevski (Croatian PEN) and Elisabeth Nordgren (Finnish PEN).

“We are at the end of the first mandate of the first Board elected three years ago during the Warsaw Congress under the new Regulations.” Carles reported. “…we now have a real capacity for collective decision-making between Congresses…we are noticing that the transformation we dreamed of six years ago, when the new structuring of International PEN started, has taken place. There are more people involved in the work of International PEN, and each person represents a specific sensitivity within our international community…and we are better prepared to achieve our task now and in the future.”

The modernization and reform of governance also applied to PEN’s more than 130 centers with agreement that new centers from unrepresented parts of the world needed to be developed and centers that no longer functioned or worked in harmony with PEN’s Charter should be disbanded though there was often reluctance among PEN members to close a center.

At the Macedonia Congress, a particular PEN-like debate arose over the Langue d’Oc Center which no longer functioned. Langue d’Oc, or the Language of the Troubadours, was still spoken in a region in the South of France, in part of Italy and in one valley in Spain. The center’s president, whose name was the same as a great literary character, had worked on PEN’s Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights with PEN’s Committee on Translation and Linguistic Rights half a dozen years before, and one member was still eager to keep the center going as a cause of minority languages. But the elderly outgoing President was not able to help, according to Jane Spender, PEN’s Administrative Director, who communicated or tried to communicate, with these centers. The center no longer functioned, had no office or contacts who replied, she reported. Before the center was declared closed, however, former International Secretary Alexander Blokh proposed that it be declared dormant and during the ensuing year French PEN writers who knew some of the members would “try to wake them up.” The Portuguese PEN delegate also offered to help as did the Esperanto, Slovene and Galician delegates. A similar lifeline was given to the inactive Welsh center by English PEN who agreed to perform the same role.

At PEN’s Congress the following year in Mexico, the interventions confirmed that after a year of dormancy neither center had rallied and so the Assembly voted to close the centers. In both cases new writers then came forward, and a few years later a new and active Welsh Center and Langue d’Oc Center formed and were elected back into PEN’s Assembly.

At the Macedonia Congress three brand new centers—Kyrghyz, Sierra Leone, and Tibet—joined the PEN family. It was in this fashion that PEN International pruned, renewed and broadened its base in civil society among nations and cultures and languages.

Lake Ohrid in the hills of North Macedonia between Macedonia and eastern Albania

Next Installment: PEN Journey 27: San Miguel Allende and Other Destinations–PEN’s Work Between Congresses

PEN Journey 17: Gathering in Helsingør

PEN International celebrates its Centenary in 2021. I’ve been active in PEN for more than 30 years in various positions and now as an International Vice President Emeritus. With memories stirring and file drawers of documents and correspondence bulging, I am a bit of a walking archive and have been asked by PEN International to write down memories. I hope this personal PEN journey will be of interest.

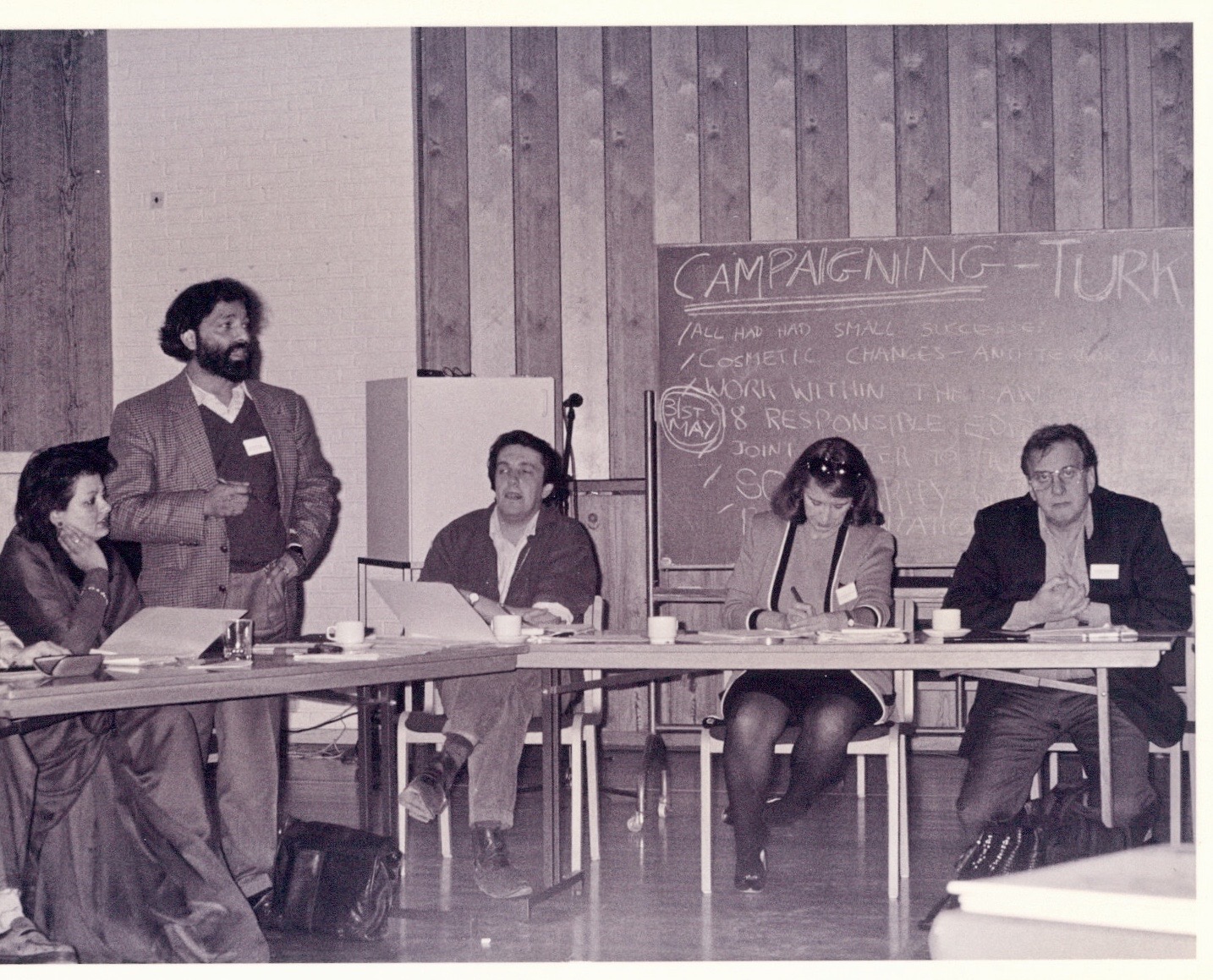

What I remember most about the gathering of colleagues from 28 countries—31 PEN centers—51 of us in all at the first Writers in Prison Committee conference in 1996 was the seriousness of purpose and intellect during the day and the fun and talent in the evenings.

Hosted by Danish PEN, writers from every continent gathered at a university in Helsingør—known in English as Elsinore, the home of Shakespeare’s Hamlet—where we met in workshops and ensemble during the day to shape and refine our work on behalf of writers and freedom of expression around the world. But in the evening we were at a small university in a small city without transportation or distraction so we entertained ourselves. Each delegate displayed talents—from poetry reading to song to dance to musical performances.

As Chair of the WiPC gathering, I’d brought none of my own writing to read and was left to exhibit meager other talent which consisted of playing a few opening bars of Für Elise on the piano and whistling tunes with my far more talented Danish and Russian colleagues. Archana Singh Karki from Nepal in flowing red dress entertained with her graceful dance; Siobhan Dowd, our Irish former WiPC director and Freedom of Expression director at American PEN, silenced us with her soulful Irish folk songs, sung acapella; Sascha, Russian PEN’s General Secretary, not only whistled robustly but recited his poetry, which I was told I should be glad I didn’t understand with its bawdy content; Sam Mbure from Kenya and Turkish/English novelist Moris Farhi also read and recited work. PEN International President Ronald Harwood joined the discussions in the day and was audience in the evening. I don’t recall if Ronnie offered his own work, but we all bonded in our mission and in our support for the talent in the room.

Entertainment in the evening: From the top left—Jens Lohman (Danish PEN), Alexander (Sascha) Tkachenko (Russian PEN), Joanne Leedom-Ackerman (Chair of WiPC)in a whistling song; Rajvinder Singh (German PEN, East) accompanying Archana Singh Karki (Nepal PEN) in dance; Siobhan Dowd (at piano—English & American PEN) with Moris Farhi (reading—English PEN); Sam Mbure (reciting—Kenyan PEN); Niels Barfoed (reading—Danish PEN)

During the three days, we fine-tuned our methods of working on and campaigning for our main cases, those writers who were imprisoned, attacked or threatened because of their writing, often their nonviolent voice of protest against authoritarian regimes. We considered PEN’s decision-making on borderline cases such as those which included drug charges, advocacy of violence, pornography, hate speech, terrorism. These were not categories we normally took on as cases. We discussed when we might take up such a case or assign them to investigation or judicial concern. We laid the groundwork for more joint actions among centers and other organizations such as the U.N., OSCE and IFEX, the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.